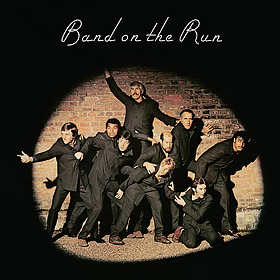

- Album This interview has been made to promote the Band On The Run (UK version) Official album.

Timeline

More from year 1974

Songs mentioned in this interview

Unreleased song

Don't Let The Sun Catch You Crying

Officially appears on Tripping The Live Fantastic

Give Ireland Back To The Irish

Officially appears on Give Ireland Back To The Irish

Officially appears on Helen Wheels / Country Dreamer

Officially appears on Revolver (UK Mono)

Officially appears on Hey Jude / Revolution

Officially appears on Hi, Hi, Hi / C Moon

Officially appears on Unplugged (The Official Bootleg)

Officially appears on Let It Be / You Know My Name (Look Up The Number)

Officially appears on Live And Let Die / I Lie Around

Officially appears on Long Tall Sally

Officially appears on Mary Had A Little Lamb / Little Woman Love (UK)

Officially appears on Please Please Me / Ask Me Why

Officially appears on Seaside Woman / B-Side To Seaside

Officially appears on Choba B CCCP

Officially appears on Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (UK Mono)

You've Got to Hide Your Love Away

Officially appears on Help! (Mono)

Officially appears on Band On The Run / Zoo Gang

Interviews from the same media

Apr 30, 1970 • From RollingStone

Aug 31, 1972 • From RollingStone

Jun 17, 1976 • From RollingStone

Paul McCartney by Paul Gambaccini

Mar 30, 1979 • From RollingStone

Paul McCartney: Ten Days in the Life

Feb 20, 1980 • From RollingStone

Paul McCartney: The Rolling Stone Interview

Sep 11, 1986 • From RollingStone

Jun 15, 1989 • From RollingStone

Paul McCartney: One for the Road

Feb 08, 1990 • From RollingStone

Feb 10, 1994 • From RollingStone

Paul McCartney on 'Beatles 1,' Losing Linda and Being in New York on September 11th

Dec 06, 2001 • From RollingStone

Spread the love! If you like what you are seeing, share it on social networks and let others know about The Paul McCartney Project.

Interview

The interview below has been reproduced from this page . This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

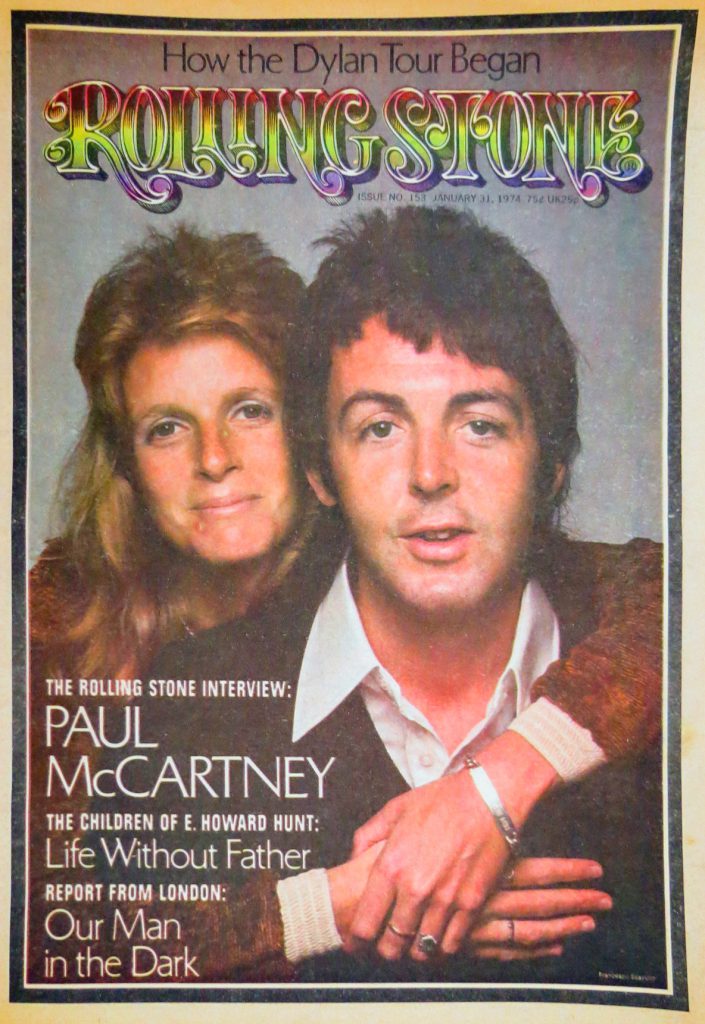

This January marks the tenth anniversary of the Beatles’ appearance on the American charts. Last month Rolling Stone conducted its first full-scale interview with Paul McCartney, in six sessions starting in a London recording studio and ending on a New York street. The New York sessions took place the day after McCartney had entered the US for the first time in two years, visa problems stemming from two marijuana violations now finally resolved.

McCartney was cautious in his responses during the first two sessions. He and Linda remembered being on vacation in Scotland when they were first shown John Lennon’s lengthy interview (Rolling Stone Number 74 and Number 75, January 21st and February 4th, 1971), and having been deeply hurt by it. At first he seemed to want to avoid the kind of controversy Lennon’s interview had generated but in later conversations he became freer with his answers.

Because the various sessions were necessarily disconnected, our text does not follow in all cases the actual sequence of questions. For example, McCartney’s discussion of his legal difficulties is compiled from three separate conversations. One of those discussions was prompted by an incident on a New York street. We were walking down 54th Street towards the New York office of Eastman and Eastman, attorneys—Lee and John Eastman, father and brother of Linda McCartney (whose photographs illustrate this interview).

A man in a gray suit with a colorful umbrella approached McCartney and asked, “Mr. McCartney? This is for you.” It was an American copy of a process from Allen Klein that had been served on Paul two weeks before in London. An outraged PR man howled; McCartney smiled and told the man, “Thank you very much.” He was being sarcastic.

The villain of the scenario, so far as he was concerned, was not the man in the gray suit, but Klein himself, whom McCartney calls a “punk.” McCartney claims he sued his fellow ex-Beatles in High Court because it was the only way to sue Klein. When we queried the head of ABKCO Industries about the suit, he seemed to relish the new confrontation. “He now has the opportunity to say anything he wants in court,” Klein told us. “He has his opportunity to fight me face to face. I am welcoming it. Now he’s in the same ring with me. Isn’t that what he wanted?”

John Eastman made this statement concerning the Beatles/Apple/Klein suits and Paul’s involvement in them:

“John Lennon, George Harrison, Ringo Starr, Yoko Ono, Apple and others started an action in England against ABKCO and Klein. This complaint alleges ABKCO and Klein took excessive commissions, practiced fraud, suggested conduct which would have been a fraud on the tax authorities in the US and UK, mismanaged Bangla Desh and otherwise mismanaged the affairs of the complainant. This action is now pending against ABKCO and Klein.

“ABKCO then sued Lennon, Harrison, Starr, Yoko Ono, Apple and other related companies in the US. It claims damages against them of $63,461,372.87 plus future earnings.

“ABKCO also joined Paul, claiming conspiracy. Its only claim against Paul is that Paul conspired with Yoko Ono, John Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr as well as Bag Production and other corporations wantonly, maliciously, fraudulently, wrongfully and intentionally without justification in law or fact to damage or injure plaintiff (ABKCO).’ Damages are sought for this alleged conspiracy of $34 million plus interest.”

Our interviews were delayed some months, first by a Wings tour and later by a series of recording sessions in Nigeria. Even after that wait, the McCartneys seemed surprised at how much we wanted to know. In the end they were interviewed in a London recording studio, Paul’s Soho office, Lee Eastman’s offices and apartment in New York (where baby Stella McCartney wore the interviewer’s watch on her foot) and the studio of cover photographer Francesco Scavullo. As the interview begins, Paul is telling how he wrote one of the songs he recorded in Nigeria. —P.G.

***

Paul: We were in Jamaica on holiday and we were staying in a little house outside Montego Bay, and we read in the local newspaper, The Daily Gleaner, that Dustin Hoffman and Steve McQueen were in town filming Papillon. They were just along the coast from us. We were saying it would be great to meet him, have dinner with him, so Linda rang up. She’s good at that, I’m always a bit embarrassed.

We got friendly and were chatting away. We’d been talking about songwriting, and Dustin was saying he thought it was an incredible gift to be able to write a song about something. People think that, but I always maintain it’s the same as any gift. It probably is more magical because it’s music, and I think it is more magical. But take his acting talent. It’s great. I was saying, “It’s the same as you and acting, when the man says ‘Action!’ you just pull it out of the bag, don’t you? You don’t know where it comes from, you just do it! How do you get all of your characterizations? It’s just in you.

So he says, “You mean you can just do it, like that?” He was lovely, Dustin. [Does Dustin Hoffman impersonation.] “You can just do it?” We went back a couple of days later and he said, “I’ve been thinking about this, I’ve seen a little thing in Time magazine about Picasso, and it struck me as being very poetic. I think this would be really great set to music.” It was one of those Passed On bits, you know, Transition or whatever they call it. . . . [Sees unusually dressed studio assistant.] . . . Transvestite. . . . So he says there’s a little story here. In the article he supposedly said, “Drink to me, drink to my health, you know I can’t drink anymore.” He went to paint a bit, and then he went to bed at three in the morning. He didn’t wake up the next morning and they found him, dead.

I happened to have my guitar with me, I’d brought it around, and I said, yeah, sure. I strummed a couple of chords I knew I couldn’t go wrong on and started singing “Drink to me, drink to my health,” and he leaps out of his chair and says, “Annie! Annie!” That’s his wife. He says, “Annie! Annie! The most incredible thing! He’s doing it! He’s writing it! It’s coming out!” He’s leaping up and down, just like in the films, you know. And I’m knocked out because he’s so appreciative. I was writing the tune there and he was well-chuffed.

Then we went to Nigeria and we were working in Ginger’s studio—Ginger Baker/ARC Studio in Lagos, nice studio down there. We thought we’d do this Picasso number, and we started off doing it straight. Then we thought, Picasso was kind of far out in his pictures, he’d done all these different kinds of things, fragmented, Cubism and the whole bit. I thought it would be nice to get a track a bit like that, put it through different moods, cut it up, edit it, mess around with it—like he used to do with his pictures. You see the old films of him painting, he paints it once and if he doesn’t like it he paints it again, right on top of it, and by about 25 times he’s got his picture. So we tried to use this kind of idea, I don’t know much about it to tell you the truth, but what we did know we tried to get in the song, sort of a Cubist thing.

Then there was the trouble in Nigeria with Fela Ransome Kuti [Ex-Ginger Baker’s Air Force].

Paul: You heard about that? All it was was we were recording in Lagos. Lately we’ve gone to two different places to record, just for the fun of it. We’ve been to Lagos and to Paris and in both of the places they say, “Why did you come here? You’ve got much better studios in England or America, you must be daft!” And we say, “Well, it’s just for the fun, it’s just to come somewhere different for a different type of turn-on, that’s all.” They never really seem to be able to understand it. I think old Fela, when he found us in Lagos, thought, “Hello, why have they come to Lagos?” And the only reason he could think of was that we must be stealing black music, black African music, the Lagos sound, we’d come down there to pick it up. So I said, “Do us a favor, we do OK as it is, we’re not pinching your music.”

They felt that they have their own little ethnic thing going and these big foreigners are taking all their bit and beating them back to the West with it. Because they have a lot of difficulty getting their sound heard in the West. There’s not an awful lot of demand, except for things like, what was it, “Soul Makossa.” Except for that kind of thing they don’t really get heard.

And they are brilliant, it’s incredible music down there. I think it will come to the fore. And I thought my visit would, if anything, help them, because it would draw attention to Lagos and people would say, “Oh, by the way, what’s the music down there like?” and I’d say it was unbelievable. It is unbelievable. When I heard Fela Ransome Kuti the first time, it made me cry, it was that good.

You’ve just had some musicians leave, haven’t you?

Paul: Our drummer [Denny Seiwell] didn’t want to come to Africa. I don’t know quite why. He was a bit nervous about coming to Africa. We’re all going to Africa to record and if the drummer won’t come, what do you do? You don’t say, “Well, we’ll see you when we get back, thanks a lot we understand.” You say, “Well, er, ummm,” and he leaves.

I think [guitarist] Henry McCulloch came to a head one day when I was asking him to play something he didn’t really fancy playing. We all got a bit choked about it, and he rang up later and said he was leaving. I said, “Well, OK.” That’s how that happened. You know, with the kind of music we play, a guitarist has got to be a bit adaptable. It was just one of those things. I don’t think there was anything wrong with them as musicians, they were both good musicians, but they just didn’t fit in.

In the film ‘A Hard Day’s Night,’ there were the stereotypes—if you remember John the thinker, Ringo the loner, and Paul the happy-go-lucky. Did you object to that?

Paul: No, I didn’t mind it. No, no; I still don’t. I was in a film. I don’t care what they picture me as. So far as I’m concerned I’m just doing a job in a film. If the film calls for me to be a cheerful chap, well, great; I’ll be a cheerful chap.

It does seem to have fallen in my role to be kind of a bit more that than others. I was always known in the Beatle thing as being the one who would kind of sit the press down and say, “Hello, how are you? Do you want a drink?” and make them comfortable. I guess that’s me. My family loop was like that. So I kind of used to do that, plus a little more polished than I might normally have done, but you’re aware you’re talking to the press. … You want a good article, don’t you, so you don’t want to go sluggin’ the guys off.

But I’m not ashamed of anything I’ve been, you know. I kind of like the idea of doing something and if it turns out in a few years to look a bit sloppy I’d say, “Oh well, sloppy. So what?” I think most people dig it. You get people livin’ out in Queens or say Red Creek, Minnesota, and they’re all wiped out themselves … you know, ordinary people. Once you get into the kind of critical bit, people analyzing you and then you start to look at yourself and start to analyze yourself, and you think, oh Christ, you got me, and things start to rebound on ya, why didn’t I put on a kind of smart image … you know, why wasn’t I kind of tougher? I’m not really tough. I’m not really lovable, either, but I don’t mind falling in the middle. My dad’s advice: moderation, son. Every father in the world tells you moderation. [Linda laughs hysterically in the background.]

British parents aren’t different . . .

Paul: No, they’re exactly the same. My dad could be the perfect American stereotype father. He’s a good lad, though; I like him, you know.

I tell you what. I think that a lot of people worried about that kind of stuff didn’t often have very good family scenes, and something happened in their family to make them bitter. OK, in the normal day-to-day life a lot of polished talk goes on . . . you don’t love everyone you meet, but you try and get on with people, you know, you don’t try and put ’em up-tight; most people don’t anyway.

So to me that’s always been the way. I mean, there’s nothin’ wrong with that; why should I go around slugging people? I really didn’t like all that John did. But I’m sure that he doesn’t now.

Have you talked to him about that?

Paul: No, but I know John and I know that most of it was just something to tell the newspapers. He was in that mood then and he wanted all that to be said. I think, now, whilst he probably doesn’t regret it, he didn’t mean every single syllable of it. I mean, he came out with all stuff like I’m like Engelbert Humperdinck. I know he doesn’t really think that. In the press, they really wanted me to come out and slam John back and I used to get pissed at the guys coming up to me and saying, “This is the latest thing John said and what’s your answer.” And I’d say, “Well, don’t really have much of an answer. He’s got a right to say . . .”—you know, really limp things, I’d answer. But I believe keep cool and that sort of thing and it passes over. I don’t believe if someone kind of punches you over you have to go kind of thumping him back to prove you’re a man and that kind of thing. I think, actually, you do win that way in the end, you know.

What was your reaction when you read that stuff at the time?

Paul: Oh, I hated it. You can imagine, I sat down and pored over every little paragraph, every little sentence. “Does he really think that of me?” I thought. And at the time, I thought, “It’s me. I am. That’s just what I’m like. He’s captured me so well; I’m a turd, you know.” I sat down and really thought, I’m just nothin’. But then, well, kind of people who dug me like Linda said, “Now you know that’s not true, you’re joking. He’s got a grudge, man; the guy’s trying to polish you off.” Gradually I started to think, great, that’s not true. I’m not really like Engelbert; I don’t just write ballads. And that kept me kind of hanging on; but at the time, I tell you, it hurt me. Whew. Deep.

Could you write a song or songs with John again?

Paul: I could. It’s totally fresh ground, right now, ’cause I just got my visa, too. About two or three days ago; and until then, I couldn’t physically write a song with John; he was in America. He couldn’t get out. I couldn’t get in. But now that’s changed so whole new possibilities are opening up. Anything could happen. I like to write with John. I like to write with anyone who’s good.

Right now you yourself are working on ‘The Mouse Gang.’

Paul: No, it’s not the Mouse Gang, it’s a show that will be called the Bruce McMouse Show.

I was thinking of ‘The Zoo Gang.’

Paul: The Zoo Gang, that’s right, that’s just a theme tune for a television show I was asked to do. Bruce McMouse is another thing. We filmed the last couple of dates at the end of Wings’ first European tour. Bruce lives under the stage, you see. [Bruce and his family are animated and their exploits are spliced in between Wings’ footage for a television film.]

Are you constantly deluged with this type of offer?

Paul: Not deluged. I get quite a few, you know. I just try and choose the ones I like the sound of. It’s not anything I plan out. I remember a thing in Rolling Stone—there’s a little bit of chat, I read the papers, you know—that said “McCartney’s going to do Live and Let Die, so it’s come to that, has it?” I thought, you silly sods. Because we were talking to another paper and when I said I was going to do Live and Let Die, the 007 thing, the reporter said, “Hey, man, that’s real hip.” So it just depends which way you look at it.

“Give Ireland Back to the Irish” was the first of your singles in eight years that didn’t sell in America and Britain.

Paul: Before I did that, I always used to think, God, John’s crackers, doing all these political songs. I understand he really feels deeply, you know. So do I. I hate all that Nixon bit, all that Ireland bit, and oppression anywhere. I think our mob do, our generation do hate that and wish it could be changed, but up until the actual time when the paratroopers went in and killed a few people, a bit like Kent State, the moment when it is actually there on the doorstep, I always used to think it’s still cool to not say anything about it, because it’s not going to sell anyway and no one’s gonna be interested.

So I tried it, it was Number One in Ireland and, funnily enough, it was Number One in Spain, of all places. I don’t think Franco could have understood.

[At this point Paul receives word that a playback of Bruce McMouse is beginning in the control room. He excuses himself and we chat with Linda while Denny Laine plays a medley of Tim Hardin songs on the studio piano.]

Did you feel scared when ‘McCartney’ was released, since that was your debut and the first song was pegged at you?

Linda: No. I didn’t take it as seriously as I probably should have. I think it was good copy at the time to slag everything. Everybody was getting slagged, the Beatles were getting slagged. I personally didn’t realize you had to explain yourself a lot once you get into the public eye. I just carried on with my normal life, like I had in New York, and I just got all this slagging. It never really brought me down much, though.

Do you think any Mrs. McCartney in that situation would have been slagged?

Linda: I think in what was going down then, yes. There was so much trouble for everybody, not done by one particular person, that everybody was getting blamed. I still can’t look at it from the angle that I’m Mrs. McCartney. You know what I mean? I still see me as the person I’ve always been, either you like me or you don’t. Paul likes me. [Laughter.]

And stood up for you during the slagging.

Linda: He was living with me, he knows I’m a good chick, he knows I don’t have any bad motives. I’m not a grabber, I’m not any of that. He wouldn’t have married me if I had been. So he stuck by me. I just read totally bizarre stuff about myself. People would do an article on me and then an article on Yoko from childhood on up. I couldn’t believe it. It was total fantasy. I mean, none of that happened, folks.

Unlike John, who went to a solo career, Paul went to a group.

Linda: John didn’t really go to a solo career, there was the Plastic Ono Band and that. But Paul is very much a teamwork person. He doesn’t like working just on his own. He still gets nervous. He likes working with people, bouncing off people and having them bounce off him. He likes helping people.

Have you ever entertained the thought of doing a record by yourself?

Linda: Not Linda McCartney’s Great Single, no. I fool around with the songs I write, but I don’t take it as a serious career.

You do have the novelty single coming up?

Linda: Yes. I did a song, “Seaside Woman,” right after we’d been to Jamaica, about three or four years ago, I guess. Very reggae-inspired. That’s when ATV was suing us saying I was incapable of writing, so Paul said, “Get out and write a song.” And then about a week ago we went in to do a B side for it of something I’d written in Africa, some chords I wrote in Africa, and we just talk over it. It’s very sort of Fifties R&B, the Doves, the Penguins. I love that, that was my era. I’m New York, you know, Alan Freed and the whole bit.

We’re going to put the single out under the name Suzi and the Red Stripes. When we were in Jamaica, there had been a fantastic reggae version of “Suzi Q,” so they used to call me Suzi. And the beer in Jamaica is called Red Stripe, so that makes it Suzi and the Red Stripes. It’ll be out someday, but I’ve been saying “Seaside Woman” will be released since 1971 and we still haven’t bothered. It’s a bit like my photography book. Someday there will be a book.

Was it strictly through you that your father became associated with Paul as his lawyer?

Linda: It’s through me, actually. I remember saying to my father, when I’d met Paul a few times but wasn’t living with him, after Brian died, that he had helped a lot of people out of messes, could he help? He said well, I don’t know. I said it would be great because I know you could help them out. So then I introduced Paul to my dad, and they got along instantly. If he hadn’t met my father, Klein would have just hawked right in there.

[At this point we retire to the control room. Linda goes over the Walt Disney Christmas show script, then talks on the phone to someone at EMI. “I think the only bit we’d like to add is a little bit from 101 Dalmatians . . .”

[Paul talks to the engineer of Dark Side of the Moon. They marvel at its sales record, and the engineer notes that Pink Floyd are going to give him a Christmas present. “Ask for a percentage,” McCartney recommends. “It’s the best present they could give you. What that album has done so far is amazing. In France, it’s outsold Abbey Road . . .”]

How did you meet Linda?

Paul: Linda and I met in a club in London called the Bag of Nails, which was right about the time that the club scene was going strong in London. She was down there with some friends. I think she was down there with Chas Chandler and some other people, and I was down there with some friends, including a guy who used to work at the office. I was in my little booth and she was in her little booth and we were giving each other the eye you know. Georgie Fame was playing that night and we were both right into Georgie Fame.

When did you first realize you wanted to marry her?

Paul: About a year later. We both thought it a bit crazy at the time, and we also thought it would be a gas. Linda was a bit dubious, because she had been married before and wasn’t too set on settling. In a way, she thought it tends to blow things, marrying ruins it. But we both fancied each other enough to do it. And now we’re glad we did it, you know. It’s great. I love it.

Some of the critical notices on her debut performances seemed to ask where she had come from.

Paul: Yeah. Well, the answer is, nowhere, really.

Mick Jagger had that quote. He wouldn’t let . . .

Paul: … his old lady in the band, yeah. That was all very understandable at the time because she did kind of appear out of nowhere. To most people, she was just some chick. I just figure she was the main help for me on the albums around that time. She was there every day, helping on harmonies and all of that stuff.

It’s like you write millions of love songs and finally when you’re in love you’d kind of like to write one for the person you’re in love with. So I think all this business about getting Linda in the billing was just a way of saying, “Listen, I don’t care what you think, this is what I think. I’m putting her right up there with me.”

Later we thought it might have been cooler not to introduce her so bluntly. Perhaps a little more show business: “Ladies and gentlemen, I’d like to introduce you to my better half. Isn’t she sweet and coy?”

It turns out it didn’t matter, it didn’t matter one bit. At the time it was a little rough, maybe. At the time it was rough for her. None of us realized what . . . it was like someone marrying Mick, you don’t realize . . . you know there’s going to be a lot of fans who are going to hate it, but you still end up thinking, well, it’s my life. I know of a lot of rock & roll stars or just even show business people who will regulate their life to their image. It can mess you up a lot. I know a lot of guys from the old days who wouldn’t get married, even if they wanted to. Wouldn’t get married because it might affect their careers. The old management thing—”You can’t get married, all your fans are going to desert you.” So the guy doesn’t get married.

But the thing is, in a couple of years, his career is over anyway. And he didn’t get married, and he went and blew it. So I didn’t. “Well, I’m not going to let that kind of thing interfere with me.” Although I didn’t wish to blow my career, I thought it was more important to get on with living. We went ahead and just did what we felt like doing. Some of it came out possibly a bit offensive to some people, but it turns out that it didn’t matter in the first place. You just keep going.

Did your friends in music stick by you at that time or did you find it a little tough? Or did you have that many friends at the time?

I remember Ringo saying at the time “How many friends have I got?” and he couldn’t count them on one hand. And that’s what it boils down to, really. You can have millions of friends, but when someone asks you how many friends you’ve got, it depends on how honestly you’re going to answer. Because I don’t think I have that many. No one went against me or anything, I think I isolated myself a bit. It’s just one of those things. We had just met for the first time. We’re very romantic, the both of us, and we didn’t really want to hang out with anyone else.

Do you often go back to Liverpool?

We visit to keep in touch with the Liverpool scene. My family roots are up there, our kids love, it, and my brother still lives there. In fact, we’re going to make an album with him in January.

Will it come out as a Mike McGear album?

That’s right. It’s a singing thing, he’s quit comedy for the moment. We’re going to do it at Strawberry Studios in Stockport. We’ll play it by ear, it’s Mike’s album.

Is it difficult for the kids, being your daughters?

I don’t think so, I don’t think they’re going to be crazed-out kids. But it is funny sometimes. I remember I was sitting in a field and Heather was leading Mary and a little baby on a pony, and Mary just said to me, “You’re Paul McCartney, aren’t you?” When she’s talking to me normally, she’ll just call me Daddy. When there’s company around, she knows I’m Paul McCartney, in inverted commas.

It’s nice that we have all girls. If we had a son it might be harder on him, like Frank Sinatra, Jr. Everyone assumes he’ll turn out to be his dad. At the moment, there’s not much to worry about with the kids.

At your Oxford press conference you mentioned your four-year-old daughter liked the Osmonds. Linda says your ten-year-old daughter is a bit off them now . . .

Yes, she is a bit . . .

. . . but I understand you met the Osmonds in Paris, which is a very unusual situation. It must have been as much of a thrill for them to meet you as it would be for a four-year-old to meet them.

A layer cake of generations.

As we’re talking today three of the Top Six here [England] are by them, which is the greatest chart domination by a group since 1964.

They’re very liked here by a lot of the record buyers, which in Britain are the young kids.

From your personal experience, do you think they can understand how much they mean to people?

Sure they know, sure. I think Little Jimmy probably knows less than the others what’s going on, but they seem to. They’ve got that kind of American showbiz family feeling, which does work. You can put it down, but it really does work. They’ve been doing it for years on The Andy Williams Show, and they’re troupers already. You know, the kid’s only eight or something, Little Jimmy, but he’s already a little trouper. He has what a seasoned performer has.

When you were in their position, did you feel a sense of responsibility, or did you feel the world had gone crazy?

No, no. We were a band who’d been trying to make it big for a long time. When you’re trying to get to the top, when you start to get there, that’s probably the biggest thrill. You don’t think the whole world’s gone crazy; you think it’s great that they like you and you’re well-chuffed that you’re going down so well. That’s all that enters your head. I think that even Little Jimmy just thinks, “Hey, man, that’s great, that’s far-out.” You know? He just loves it. And that’s really the best way.

When you get thinking too heavily about all of this stuff, like anything, you can do so many doublethinks on it all you end up with is not liking it, which is the only hang up. When you end up not liking it then you start to do it less well. I always thought, just great, great band, great things, kids screaming, fantastic, fabulous, great, everyone’s having a good night out. That sort of thing, basically.

Were you frightened of possible negative reaction when you released your solo album, ‘McCartney’? It was your first break from the Beatles.

I was as confident as I ever am about any LP. I realize it was more kind of throwaway and done at home than any of the previous ones, but that wasn’t a reason to worry about it. You never know what people are going to think about a record anyway.

The handout on the British edition of ‘McCartney’ didn’t appear in America. Why was that?

Linda and I did a mail-out from our house. We had made up this little interview for friends and the press and sent them out with about the first hundred albums. Somebody thought it was supposed to be a thing that came with the album, probably because we didn’t explain it in the mailing. We should have said. “Enclosed find press kit.” People got the idea it came with the album, but it didn’t come out in Britain in the copies in the stores.

I had asked Peter Brown [of Apple] for a list of questions he thought might have interesting answers. Looking back, it seems a bit blunt and weird, but at the time it wasn’t meant to be. Things like, “Are you gonna be another John and Yoko?” “No, we’re gonna be a Paul and Linda.” Little silly things like that.

How did you feel people would react to Linda’s presence?

She was on Let It Be doing backup vocals. That was her first appearance, and nobody said much about that. The time we did McCartney, as it was largely recorded in the back room, she was always there. That was how she came to be on the album as much as she was.

You did have the release date close to ‘Let It Be.’

There was some hassle at the time. We were arguing over who had mentioned a release date first. It was all a bit petty. I’d pegged a release date and then Let It Bewas scheduled near it. I saw it as victimization, but now I’m sure it wasn’t.

Seeing that ‘Let It Be’ was released basically after the fact, do you wish it had not been released?

Oh, no. I don’t wish that about anything. Everything seems to take its place in history after it’s happened and it’s fine to let it stay there.

It was the first album to have the little bits on, like the type that also appeared on ‘McCartney.’

I rather fancied having just the plain tapes and nothing done to them at all. We had thought of doing something looser before, but the albums always turned out to be well-produced. That was the idea of the whole album. All the normal things that you record that are great and have all this atmosphere but aren’t brilliant recordings or production jobs normally are left out and wind up on, say, Pete Townshend’s cutting floor. It ends up with the rest of his demos.

But all that stuff is often stuff I love. It’s got the door opening, the banging of the tape recorder, a couple of people giggling in the background. When you’ve got friends around, those are the kind of tracks you play them. You don’t play them the big finished produced version.

Like “Hey Jude,” I think I’ve got that tape somewhere, where I’m going on and on with all these funny words. I remember I played it to John and Yoko and I was saying, “these words won’t be on the finished version.” Some of the words were “the movement you need is on your shoulder,” and John was saying, “It’s great! ‘The movement you need is on your shoulder.'” I’m saying, “It’s crazy, it doesn’t make any sense at all.” He’s saying, “Sure it does, it’s great.” I’m always saying that, by the way, that’s me, I’m always never sure if it’s good enough. That’s me, you know.

So when McCartney came along I had all these rough things and I liked them all and thought, well, they’re rough, but they’ve got that certain kind of thing about them, so we’ll leave it and just put it out. It’s not an album which was really sweated over, and yet now I find it’s a lot of people’s favorite. They think it’s great to hear the kids screaming and the door opening, it’s lovely.

The first of your albums with some of those little bitsy things was ‘Let It Be.’ Had you wanted to do that before?

Yes, I think so. In the back of everyone’s mind there was always that kind of thing. The sound of a tape being spooled back is an interesting sound. If you’re working in a recording studio, you hear it all the time and get used to it. You don’t think anything of it. But when the man switches on the tape machine in the middle of a track and you hear that kind of djeeoww, and then the track starts, I’d always liked all that, all those rough edges and loose ends. It gives it a kind of live excitement.

When you do have rough edges on an album, you’re open to interpretation. There’s the famous example of John and Yoko’s ‘Wedding Album,’ where the reviewer reviewed the tone on the test pressing and said that the subtle fluctuations in this tone were very arty.

The whole analysis business is a funny business, it’s almost like creating history before it’s been created. When a thing happens you immediately start analyzing it as if it was 50 years ago, as if it was King Henry VIII who said it. It is daft, actually, but you can’t blame anyone for doing it, they’ve got to write something. Unless they can say “I was around at his house and he gave me a nice cup of tea … funny little blue cups he gave it in …” they’ve got to say, well, what did you mean by this, or what was that tone.

With one song you mentioned just a few minutes ago, “Hey Jude,” everyone was trying to figure out who Jude was.

I happened to be driving out to see Cynthia Lennon. I think it was just after John and she had broken up, and I was quite mates with Julian [their son]. He’s a nice kid, Julian. And I was going out in me car just vaguely singing this song, and it was like “Hey Jules.” I don’t know why, “Hey Jules.” It was just this thing, you know, “Don’t make it bad/ Take a sad song . . .” And then I just thought a better name was Jude. A bit more country & western for me.

Once you get analyzing something and looking into it, things do begin to appear and things do begin to tie in. Because everything ties in, and what you get depends on your approach to it. You look at everything with a black attitude and it’s all black.

This other idea of Paul Is Dead. That was on for a while. I had just turned up at a photo session and it was at the time when Linda and I were just beginning to knock around with each other steadily. It was a hot day in London, a really nice hot day, and I think I wore sandals. I only had to walk around the corner to the crossing because I lived pretty nearby. I had me sandals on and for the photo session I thought I’ll take my sandals off.

Linda: No, you were barefoot.

Paul: Oh, I was barefoot. Yeah, that’s it. You know, so what? Barefoot, nice warm day, I didn’t feel like wearing shoes. So I went around to the photo session and showed me bare feet. Of course, when that comes out and people start looking at it they say, “Why has he got no shoes on? He’s never done that before.” OK, you’ve never seen me do it before, but, in actual fact, it’s just me with my shoes off. Turns out to be some old Mafia sign of death or something.

Then the this-little-bit-if-you-play-it-backwards stuff. As I say, nine times out of ten it’s really nothing. Take the end of Sgt. Pepper, that backward thing, “We’ll fuck you like Supermen.” Some fans came around to my door giggling. I said, “Hello, what do you want?” They said, “Is it true, that bit at the end? Is it true? It says ‘We’ll fuck you like Supermen.'” I said, “No, you’re kidding. I haven’t heard it, but I’ll play it.” It was just some piece of conversation that was recorded and turned backwards. But I went inside after I’d seen them and played it studiously, turned it backwards with my thumb against the motor, turned the motor off and did it backwards. And there it was, sure as anything, plain as anything. “We’ll fuck you like Supermen.” I thought, Jesus, what can you do?

And then there was “I buried Paul.”

That wasn’t “I buried Paul” at all, that was John saying “cranberry sauce.” It was the end of “Strawberry Fields.” That’s John’s humor. John would say something totally out of synch, like “cranberry sauce.” If you don’t realize that John’s apt to say “cranberry sauce” when he feels like it, then you start to hear a funny little word there, and you think “Aha!”

When you were alive and presumed dead, what did you think?

Someone from the office rang me up and said, “Look, Paul, you’re dead.” And I said, “Oh, I don’t agree with that.” And they said, “Look, what are you going to do about it? It’s a big thing breaking in America. You’re dead.” And so I said leave it, just let them say it. It’ll probably be the best publicity we’ve ever had and I won’t have to do a thing except stay alive. So I managed to stay alive through it.

A couple of people came up and said, “Can I photograph you to prove you’re not dead?” Coincidentally, around about that time, I was playing down a lot of the old Beatle image and getting a bit more to what I felt was me, letting me beard grow and not being so hung up on keeping fresh and clean. I looked different, more laid back, and so I had people coming up saying “You’re not him!” And I was beginning to think, “I am, you know, but I know what you mean. I don’t look like him, but believe me.”

You were supposedly Billy Shears, according to one of the theories.

Ringo’s Billy Shears. Definitely. That was just in the production of Sgt. Pepper. It just happened to turn out that we dreamed up Billy Shears. It was a rhyme for “years” … “band you’ve known for all these years … and here he is, the one and only Billy Shears.” We thought, that’s a great little name, it’s an Eleanor-Rigby-type name, a nice atmospheric name, and it was leading into Ringo’s track. So as far as we were concerned it was purely and simply a device to get the next song in.

Your two big television shows were the ‘James Paul McCartney’ and ‘The Magical Mystery Tour’ shows. How were these conceived?

The Mystery show was conceived way back in Los Angeles. On the plane. You know they give you those big menus and I had a pen and everything and started drawing on this menu and I had this idea. In England they have these things called Mystery tours. And you go on them and you pay so much and you don’t know where you’re going. So the idea was to have this little thing advertised in the shop windows somewhere called Magical Mystery Tours. Someone goes in and buys a ticket and rather than just being the kind of normal publicity hype of magical . . . well, it never is magical, really . . . the idea of the show was that it was actually a magical run—a real magical trip.

I did a few little sketches myself and everyone else thought up a couple of little things. John thought of a little thing and George thought of a scene and we just kind of built it up. Then we hired a coach and picked actors out of an actor’s directory and we just got them all along with the coach and we said, “OK, act.” An off-the-cuff kind of thing.

The James Paul McCartney show were these people who wanted us to do a TV show and they said they wanted a nice show and said you can do it any way you want. This seemed like a good opportunity, you know, to kinda get on the telly. So that one was just worked up that way. We met the guy when we went to Morocco. We were on holiday then and they came out and we sat around the pool and talked about various ideas and came back to England and did it.

Were you sorry ‘The Magical Mystery Tour’ was not shown in America?

At the time, hey, I thought, “Oh, blimey,” but … eh … it started out to be one of those kind of things. Like The Wild One, you know, Marlon Brando … at the time it couldn’t be released. The interest in it came later. The interest started to grow, you know. Magical Mystery Show was a bit like that … well, whatever happened to it … that’s a bit magical itself. Like the Stones’ Rock and Roll Circus. You know, what happened to that, you know. I mean, I’d like to see that. So all of those things work out well. You’ve got to be patient. Everything like that works out well. I think it was a good show. It will have its day, you know.

There was an interesting reaction to ‘James Paul McCartney.’ Some people liked some parts and didn’t like others.

I can understand that. You know, I think a lot of people thought we could have done more . . . could have done a better show. It was a little bitty [disjointed]. That was a fair comment, but I got a lot of letters from people, you know, just people, old people, from like Red Creek, Minnesota, just saying, “Hey man, dug the show, you know.”

You told me you still ask your friends, ‘Is this really good?’ And Linda mentioned that you still get nervous about the work. And so does this mean you watch critical notices very closely?

No, I don’t like criticism whatever. I don’t think I ever liked it when my dad said, I don’t like your trousers. But I went through a difficult period where I started to listen to what the newspapers have to say . . . about me . . . and say, some guy would be sittin’ in New York all hung up thinking, “Well, that’s not as good as I woulda wanted.” And I thought, “Well, blimey, that’s only one guy. I’m not going to take it as gospel.”

Linda mentioned you “bounce off” people. After you left George Martin and the other three, was Linda the only person to bounce your ideas off of?

For a while, yes. Oh yes.

Did you miss not having more people? Is there anyone you ask now outside of people in the band?

Sometimes now I mainly bounce off myself. I do that more now, call it what you will—maturity? Sometimes if a friend is in the studio I’ll ask for their opinion and that will make it easier on me. The laugh of all this is I say all this rubbish and it all changes the next day.

I still read the notices and stuff and they’re usually bum ones when you’re expecting them to be great. Like after Ram, there were a lot of bum notices after Ram. But I keep meetin’ people wherever I go, like I met someone skiing. As he skied past me he said, “I loved Ram, Paul.” So that’s really what I go by. Just the kind of people who flash by me in life. Just ordinary people and they said they loved it. That’s why I go a lot by sales, not just for the commercial thing. Like if a thing sells well, it means a lot of people bought it and liked it.

Does that mean, then, that you didn’t think too much in retrospect of ‘Wild Life’? Because of all your albums . . .

No, ah, I quite liked it. I must say you have to like me to like the record. I mean, if it’s just taken cold, I think it wasn’t that brilliant as a recording. We did it in about two weeks, the whole thing. And it had been done on that kind of a buzz we’d been hearing about how Dylan had come in and done everything in one take. I think in fact often we never gave the engineer a chance to even set up a balance. There’s a couple of real big songs on there, that only freaks or connoisseurs know.

Well, “Tomorrow.”

Yeah, “Tomorrow” is one of them. It’s like, when I’m talking to people about Picasso or something and they say, well, his blue period was his only one that was any good. But for me, if the guy does some great things then even his downer moments are interesting. His lesser moments, rather, because they make up the final picture. Some moments seem less, he was going through kind of a pressure period. You know, you can’t live your life without pressure periods. No one I know has.

You mentioned Dylan sort of being an inspiration for doing ‘Wild Life’ the way you did it . . . He’s going on the road, of course, this month.

With the Band…

Does this in any way motivate you, inspire you?

No, not particularly. I mean, I’ve just been on the road last year, so my being . . . doing that just might have inspired him; I don’t know, you know. He’s a great guy, Dylan; he’s a musician, and stuff, and he’s a great spirit. Love him, you know.

Do you think he influenced you at all?

Oh, yes. Very heavily. I think the first time was in “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away.” That was John’s song. Then there was a good deal of influence in the Hard Day’s Night and Help! periods. Certain chords, the acoustic bit. We liked him. We met him when we came to New York and we were together awhile. He came to one of my sessions when I was doing Ram in New York.

You mentioned in the studio that you were influenced in a recent session by Marvin Gaye’s “Trouble Man.” Do you think Fela or someone else might misconstrue this?

Being influenced by something and stealing something are two different things. When you hear the track we did and hear Marvin Gaye’s you probably would never know they were related. I may be influenced by something, but it’s in my head and doesn’t necessarily show in the song. “Here, There and Everywhere” was supposed to be a Beach Boys song, but you wouldn’t have known.

“Hi, Hi, Hi” was the one that brought you back to the Top Ten, after “Give Ireland Back to the Irish” and “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” although in Britain they played “C Moon” because “Hi, Hi, Hi” was banned by the BBC.

I thought the “Hi, Hi, Hi” thing could easily be taken as a natural high, could be taken as booze high and everything. It doesn’t have to be drugs, you know, so I’d kind of get away with it. Well, the first thing they saw was drugs, so I didn’t get away with that, and then I just had some line “Lie on the bed and get ready for my polygon.”

The daft thing about all of that was our publishing company, Northern Songs, owned by Lew Grade, got the lyrics wrong and sent them round to the radio station and it said, “Get ready for my body gun,” which is far more suggestive than anything I put. “Get ready for my polygon,” watch out baby, I mean it was suggestive, but abstract suggestive, which I thought I’d get away with. Bloody company goes round and makes it much more specific by putting “body gun.” Better words, almost.

It made it anyway in the States.

Yeah, well, the great laugh is when we go live, it makes a great announcement. You can say “This one was banned!” and everyone goes “Hooray!” The audience love it, you know. “This next one was banned,” and then you get raving, because everyone likes to. Everyone’s a bit anti-all-that-banning, all that censorship. Our crew, our generation, really doesn’t dig that stuff, as I’m sure you know.

“Helen Wheels” has done better in America than England, as have many of your records past, back to the old days. Have you ever thought of a reason why?

The only thing I can think of is the foreigner syndrome. We’re British, and that means something to an American. It’s like some Americans who do better over here, like Cassidy and the Osmonds, even Elvis.

It’s been suggested that the Beatles provided something for Americans they had lost with the death of Kennedy—youth, happiness, freedom from inhibitions. Does that make much sense to you?

No, none at all.

In songwriting technique, how did you compose with John? How did you compose yourself and then with Linda?

Well, first, I started off on my own. Very early on I met John, and we then, gradually, started to write stuff together. Which didn’t mean we wrote everything together. We’d kind of write 80% together and the other 20% for me were things like “Yesterday” and for John things like “Strawberry Fields” that he’d mainly write on his own. And I did certain stuff on my own. So I’ve done stuff on my own.

When I said how do you compose, I meant actually sitting down and doing it. Did you use guitar, or did you use piano?

When I first started writing songs I started using a guitar. The first one I ever wrote was one called “I Lost My Little Girl” which is a funny little song, a nice little song, a corny little song based on three chords—G, G7 and C. A little later we had a piano and I used to bang around on that. I wrote “When I’m Sixty-Four” when I was about 16. I wrote the tune for that and I was vaguely thinking then it might come in handy in a musical comedy or something. I didn’t know what kind of career I was going to take.

So I wrote that on piano and from there it’s really been a mixture of the both. I just do either, now. Sometimes I’ve got a guitar in my hands; sometimes I’m sittin’ at a piano. It depends whatever instrument I’m at—I’ll compose on it, you know.

Do you start with a title or a line, or what?

Oh, different ways. Every time it’s different. “All My Loving”—an old Beatle song, remember that one, folks?—I wrote that one like a bit of poetry, and then I put a song to it later. Something like “Yesterday,” I did the tune first and wrote words to that later. I called that “Scrambled Egg” for a long time. I didn’t have any words to it. [Paul sings the melody with the words “scrambled egg… da da da da… scrambled egg…”] So then I got words to that; so I say, every time is different, really. I like to keep it that way, too; I don’t get any set formula. So that each time, I’m pullin’ it out of the air.

When did you get the idea you were going to bring in a string quartet on “Scrambled Egg”?

First of all, I was just playing it through for everyone—saying, how do you like this song? I played it just me on acoustic, and sang it. And the rest of the Beatles said, “That’s it. Love it.” So George Martin and I got together and sort of cooked up this idea. I wanted just a small string arrangement. And he said, “Well, how about your actual string quartet?” I said great, it sounds great. We sat down at a piano and cooked that one up.

How would you see George Martin’s contributions in those songs in those days?

George’s contribution was quite a big one, actually. The first time he really ever showed that he could see beyond what we were offering him was “Please Please Me.” It was originally conceived as a Roy Orbison-type thing, you know. George Martin said, “Well, we’ll put the tempo up.” He lifted the tempo and we all thought that was much better and that was a big hit. George was in there quite heavily from the beginning.

The time we got offended, I’ll tell you, was one of the reviews, I think about Sgt. Pepper—one of the reviews said, “This is George Martin’s finest album.” We got shook; I mean, “We don’t mind him helping us, it’s great, it’s a great help, but it’s not his album, folks, you know.” And there got to be a little bitterness over that. A bit help, but Christ, if he’s goin’ to get all the credit… for the whole album… [Paul plays with his children.]

The Wings tour in 1972 was the first time you had toured in six years, wasn’t it?

Yes.

Had you intended to keep it that long?

Oh, no, no, no. With the Beatles we did a big American tour, and. I think the feeling, mainly from George and John, was, “Oh, this is getting a little bit uhhh…” But I thought, “No, you can’t give up live playing, we’d be crazy to.” But then we did a concert tour I really hated and I came off stormy and saying, “Bloody hell, I really agree with you now.”

Where was that?

In America, somewhere, I can’t remember exactly. It was raining and we were playing under some sort of big canopy and everybody felt they were going to get electric shocks and stuff. We were driven off in a big truck afterwards and I remember sitting in the back of the truck saying, bloody hell, they’re right, this is stupid.

So we knew we were going to give up playing but we didn’t want to go make some big announcement, that we were giving it all up or anything, so we just kind of cooled it and didn’t go out. When anyone asked we’d say, “Oh, we’ll be going out again,” but we really didn’t think we would. So we recorded a lot and stuff and nobody felt the need to go out and play.

After six years I just thought it would be good to get out, because live shows are a lot of what it’s about. If nothing else, you get out there and see what people want. I remember at the end of the Beatles thinking that it would be good if I just went out with some country & western group. To have a sing every day surely must improve my voice a bit.

When you did start to play live again, were you very nervous?

Yes. Very nervous. The main thing I didn’t want to face was the torment of five rows of press people with little pads all looking and saying, “Oh, well, he’s not as good as he was.” So we decided to go out on that university tour, which made me less nervous because it was less of a big deal. We went out on that tour and by the end of that I felt quite ready for something else, and we went to Europe. I was pretty scared on the Europe tour. That was a bit more of a big deal, here he is, ladies and gentlemen, sold all the tickets out… I had to go on with a band I really didn’t know much. We decided not to do any Beatle material, which was a killer, of course, because it meant we had to do an hour of other material, and we didn’t have it, then. I didn’t have something like “My Love” that was sort of mine. I felt like everyone wanted Beatles stuff, so I was pretty nervous on that.

But by the end of the Europe tour I felt better, and at the end of the British tour I felt good. By the time we did the British tour I knew we could get it easily and that I could get it going. Everyone digs it, and there’s enough stuff not to be nervous.

On the Wings tour, the one song you did from the past was “Long Tall Sally.”

The first time I ever sang on a stage I did “Long Tall Sally.” I must have been pretty young, probably 14; I feel like I might have been 11, I don’t know. We went to stay with our parents at a holiday camp called Butlins, a branch in Wales. They used to have these talent shows, and one of my cousins-in-law was one of the red coats who had something to do with the entertainment. He called us up on the stage, I had my guitar with me. Looking back on it, it must have been a put-up job, I don’t know what I was doing there with my guitar. I probably asked him to get me up or something. I went up with my brother Mike, who had just recovered from breaking his arm and looked all pale. He had his arm in a big sling. We used to do an Everly Brothers number, something like “Bye Bye Love.” I think it might have been “Bye Bye Love,” in fact. We did that, and then I finished with “Long Tall Sally.”

Ever since I heard Little Richard’s version, I started imitating him. It was just straight imitation, really, which has gradually become my version of it as much as Richard’s. I started doing it in one of the classrooms at school, it was just one of the imitations I could do well. I could do Fats Domino, I could do Elvis, I could do a few people. [Smiles.] I still can! “I’m walking, yes indeed, I’m …” [Does Fats Domino impersonation.] “Thank you very much, ladies and gentlemen.” [An Elvis impersonation.] That’s Elvis.

Did many of those black artists appeal to you in the late Fifties and early Sixties? John did several Motown songs.

Yes, very much. I loved all that stuff. Those were my favorites, definitely.

When did you first think you wanted to be in a band?

I didn’t think I wanted to be in one; I wanted to do something in music and my dad gave me a trumpet, for my birthday. I went through trying to learn that. But my mouth used to get too sore. You know, you have to go through a period of gettin’ your lip hard. I suddenly realized I wouldn’t be able to sing if I played trumpet. So I figured guitar would be better. It was about the time that guitar was beginning to be the instrument. So I went and swapped my trumpet for a guitar and I got that home and couldn’t figure out what was wrong and I suddenly decided to turn the strings around and that made a difference and I realized I was left-handed. I started from there, really; that was my first kind of thing, and then once you had a guitar you were then kind of eligible for bands and stuff. But I never thought of myself being in a band.

One day I went with this friend of mine. His name was Ivan [Vaughn]. And I went up to Woolton, in Liverpool, and there was a village fete on, and John and his friends were playing for the thing. My friend Ivan knew John, who was a neighbor of his. And we met there and John was onstage singing “Come little darlin’, come and go with me. . .”

The Del Vikings’ “Come Go With Me”?

But he never knew the words because he didn’t know the record, so he made up his own words, like “down, down, down, down, to the penitentiary.” I remember I was impressed. I thought, wow, he’s good. That’s a good band there. So backstage, back in the church hall later, I was singing a couple of songs I’d known.

I used to know all the words to “Twenty Flight Rock” and a few others and it was pretty much in those days to know the words to that. John didn’t know the words to many songs. So I was valuable. I wrote up a few words and showed him how to play “Twenty Flight Rock” and another one, I think. He played all this stuff and I remember thinking he smelled a bit drunk. Quite a nice chap, but he was still a bit drunk. Anyway, that was my first introduction, and I sang a couple of old things.

I liked their band, and then one of their friends who was in the band, a guy called Pete Shotton who was a friend of John’s, saw me cycling up in Woolton one day and said, “Hey, they said they’d quite like to have you in the band, if you’d like to join.” I said, “Oh, yeah, it’d be great.” We then met up somewhere and I was in the band.

I was originally on guitar. The first thing we had was at a Conservative Club somewhere in Broadway, which is an area of Liverpool, as well as New York. There was a Conservative Club there and I had a big solo, a guitar boogie. I had this big solo and it came to my bit and I blew it. I blew it. Sticky fingers, you know. I couldn’t play at all and I got terribly embarrassed. So I goofed that one terribly, so from then on I was on rhythm guitar. Blown out on lead!

We went to Hamburg, and I had a real cheap guitar, an electric guitar. It finally blew up on me, it finally fell apart in Hamburg. It just wasn’t used to being used like that. Then I was on piano for a little while. So I went from bass to lead guitar to rhythm guitar to piano. I used to do a few numbers like Ray Charles’ “Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying” and a couple of Jerry Lee Lewis’ like “High School Confidential.”

Then Stuart [Sutcliffe] left the group. He was the bass player. He lent me his bass, and I played bass for a few weeks. I used to play it upside down. And he used to have piano strings on it, because you couldn’t get bass strings. They were a bit rare, you know, and they cost a lot, too, about 2 pounds for one string. So he would cut these big lengths of piano strings from the piano and wind them on this guitar. So I played that upside down for a while. I’m pretty versatile, I’ll give that to myself. I wasn’t very good, but I was versatile.

I’m in Hamburg, and I have a little bit of money together, and finally saved enough money to buy myself a Hoffman violin bass. It was my bass, then, that was the one. And I became known for that bass, a lot of kids got them. That was my big pride and joy, because it sounded great.

And that was it, basically. The rest you know.

In America, the anthology album [‘Beatles 1967-70’] and ‘Red Rose Speedway’ were back to back Number Ones. You were replacing yourself. Did that strike you as odd?

I thought it was good, rather than odd, because obviously the big hang up after the Beatles broke up was, and really still is, can any of them be as good as the unit? The answer in most people’s minds, I think, is “No. They can’t.” Because the unit was so good.

Were you glad those anthology albums were released for the historical record or to combat the bootleggers?

The bootlegging thing was one of the reasons. I didn’t take an awful lot of interest in them, actually. I still haven’t heard them. I know what’s on them because I’ve heard it all before, you know. I haven’t really taken much interest in Beatles stuff of late just because there has been this hangover of Apple and Klein. The whole scene has gone so bloody sick. The four ex-Beatles are totally up to here with it. Everyone wants it solved so everyone can get on with being a bit peaceful with each other.

There was a lawsuit recently, the three others against Klein.

Of course, I loved that. My God, I hope they win that one. That’s great. You see, apart from everything that went down, all the little personal conflicts, the reason why I felt I had to do what I had to do, which ended up specifically as being I had to sue the other three, was that there was no way I could sue Klein on his own, which is what I wanted to do. It took me months to get over the fact. I kept saying, I can’t sue the other three, just because it’s very hard news to go suing someone you like, and no matter what kind of personal things were going down and John writing songs about me and all that stuff, I still didn’t feel like the coolest thing in the world was to go and sue them. But it actually turned out to be the only way to stop Klein, so I had to go and do it.

Then it all started to come out, you know, that Klein had persuaded George – I don’t know how much of this is libelous –

Our lawyers will take out whatever is libellous.

Klein made his way into George’s big songwriting company, which is George’s big asset. The main one was the song “Something,” that was on Abbey Road. That was kind of George’s great big song, George’s first big effort, and everyone covered it and it was lovely and made him lots of money that he could give away, which is his thing, you know. It was a great thing for him. Well, it turns out that Klein has got himself into that company. Not only paid 20% [the percentage Klein claimed to have gotten from Abbey Road]—there’s a thought now that he’s claiming he owns the company!

It’s those kinds of little weird trips. Now the only good thing I feel is that I wasn’t wrong. I would have felt really bad if I was wrong and the guy was really a goodie all along and I’d gone and stuck my big nose in there like the pot calling the kettle black. But it turns out he is the type of man who wants to own it for himself and not the type of man who believes the artist should have it and do what he wants with it, which is what I believe.

He was once quoted in New York magazine as saying he was going to roast your ass.

Yeah, well, he never did, you know, and that’s cool. He wouldn’t get near my ass to roast it, anyway. Punk.

You mentioned you had to sue the other three to get at Klein. What was Klein doing that made you have to sue?

Basically, I was being held to my obligations under an old contract. I would have to just sit, lump it, and let him be my manager, which I didn’t want.

So I was told I could sue him. I said, “Great, I’ll sue him.” Then they said, “There’s one catch, you have to sue Apple”—and that meant suing the other three. For two months I sat around thinking, “I can’t do this.” Not that I didn’t see the others. I did, and kept asking them to let me out and they said, “No, Allen says there would be tax complications.” I said, “I don’t give a damn about tax considerations, let me go and I’ll worry about the tax considerations. I didn’t want to be an ABKCO-Managed Industry.” It was weird. My albums would come out saying “An ABKCO Company,” and he wasn’t even my manager.

As it turns out, it was the best thing, because that got the receiver in there and froze the money and gave everybody time to think about it. He’s still managed to get $5 million transferred to his own company, five million for management [the exact amount is subject matter of present litigation].

He has a very special gift for talking his way. He’ll use his Playboy interviews, and he’ll probably ask for a Rolling Stone interview after mine. Even a murderer has a great line in his own defense. But he’s nothing more than a trained New York crook. John said, “Anyone whose record is as bad as this can’t be so bad.” But that was Lennon-esque crap, which John occasionally did; utter foolishness. Klein had already been convicted on ten counts of income tax. [Criminal docket 66-72 of US District Court, Southern District of New York, shows one Allen Klein found guilty January 29th, 1971, on ten counts of “unlawfully failing to make & file returns of Federal income taxes and FICA taxes withheld from employees’ wages.” Conviction affirmed on appeal by US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit November 19th, 1971.] Somebody who’s been convicted ten times can’t be all clean. [Growing more emotional] My back was against the wall. I’m not proud of it. But it had to be done. To him, artists are money. To me, they’re more than that.

If Klein was the big reason for the breakup of Apple, do you think there would have been difficulties anyway without him?

I think there would have been difficulties. Had the Eastmans come in like I wanted, the others would have feared I was trying to screw everyone for the Eastmans. It would have been a bit hard for the others to swallow, I’m afraid, since the Eastmans were so close to me. But they didn’t want to screw anybody, and the way it’s turning out they’re settling up most of it anyway. Some people say, “People are all the same in business,” but they’re not.

I think the Apple thing was great. As it turned out, the one thing about business is that it does have to be looked after. If you have paperwork and bills and royalties and accounts and stuff, they all have to be handled very well, or else things get lost and then accountants have great difficulty in making up the final picture for taxes.

Apple was together in a lot of other ways. Although he didn’t get treated brilliantly at Apple, it was right for James Taylor to make his first record then. I think it was shameful of them to sue him afterwards, but I think that was largely Klein’s instigation because of the way he works. He’s kind of “OK, git the bastard. He’s left us and he’s a success, let’s sue him. We got him, we got his contract.”

But I still think all the records that came out of it, Billy Preston and James Taylor, Badfinger, Mary Hopkin, all the people we did take on all had very good records. George, even with the Radha Krishna Temple, I think that’s great stuff. I don’t think you can fault any of the artistic decisions. Looking back on it I think it was really a very successful thing.

The main downfall is that we were less businessmen and more heads, which was very pleasant and very enjoyable, except there should have been the man in there who would tell us to sign bits of paper. We got a man in who started to say, come on, sign it all over to me, which was the fatal mistake.

Just as I was going to do a radio show interview the other day, just as I was walking in, this feller walked up to me and said, “Hello, Paul,” and I thought I’d seen him somewhere before. He looked kind of middle-aged, 50ish, and I thought, “What’s he want with me? Looks a bit dubious.” He pushed a little bit of paper in me hand, he said, “I don’t want to embarrass you, Paul, I’m sure you know what this is all about, but I’ve got my job to do.” A wife and three kids, all that. So I walked on, muttering, looked at the bit of paper and it says “ABKCO hereby sue you, John, George, Ringo and everything you’ve ever been connected with,” in so many words, companies I’d never even heard of. “Sue you all for the sum of $20 million.” That is the latest little line.

I’m not trying to be immodest by classing myself with Van Gogh or with the biggies in the artistic world, but it is just a pure continuation of that kind of story. The whole idea of whoever makes the thing not being given the profits of it isn’t a new idea. I think it’s a joke, trying to sue us for that amount of money. It is just purely that he thinks, in some way, that he owns us. The laugh is that on that whole Klein thing there is one key thing which I luckily never would sign, so I feel a little bit out of that one, I must say.

Linda mentioned Lew Grade’s claim that she couldn’t write.

That was an old one. Around that time we had millions of suits flying here, flying there, George wrote the “Sue Me, Sue You Blues” about it. I’d kicked it all off originally, having to sue the other three Beatles in the High Court, and that opened Pandora’s box. After that everybody just seemed to be suing everybody.

Meanwhile Lew Grade suddenly saw his songwriting concessions, which he’d just paid an awful lot of money for, virtually to get hold of John and I, he suddenly saw that I was now claiming that I was writing half my stuff with Linda, and that if I was writing half of it she was entitled to a pure half of it, no matter whether she was a recognized songwriter or not. I didn’t think that was important, I thought that whoever I worked with, no matter what the method of collaboration was, that person, if they did help me on the song, should have a portion of the song for helping me. I think at the time their big organization suddenly thought, “Hello, they’re pulling a fast one, they’re trying to get some of the money back,” whereas in fact, it was the truth. So they slapped vast amounts on us, I can’t remember what.

I wrote Sir Lew Grade a long letter saying, “Don’t you think I ought to be able to do this and do that and don’t you think I’ve done enough and don’t you think I’m OK, and—Hey, man, why have you gotta sue me?” He wrote me back a very rational letter. I can’t remember exactly what it said, but it was a very nice letter. He’s actually OK, Lew, he’s all right.

You did a TV show for him.

After it, yeah, that’s right. All the suits were dropped by then. Bit me tongue . . .

When was the last time you saw George?

George? It’s been a little while.

Had George invited you to the Bangla Desh benefit?

George invited me, and I must say it was more than just visa problems. At the time there was the whole Apple thing. When the Beatles broke up, at first I thought, “Right, broken up, no more messing with any of that.” George came up and asked if I wanted to play Bangla Desh and I thought, blimey, what’s the point? We’re just broken up and we’re joining up again? It just seemed a bit crazy.

There were a lot of things that went down then, most of which I’ve forgotten now. I really felt annoyed—”I’m not going to do that if he won’t bloody let me out of my contract.” Something like that. For years there had been problems as to why the other three felt they couldn’t just rip up our partnership agreement. I thought it was crazy if we had split up as a band to have this piece of paper still going on. We were all tied into it and I wanted to break it up and they said, “Tax, you can’t.” Klein was saying, “You can’t do it, lads, you’ve got to stay together,” and I think I know why he was saying it. He was telling the others it was tax and it was impossible and stuff.

There was an awful lot of that, and a lot of what I did around about then was just out of bitterness at all that. I thought, “This is crazy, no one likes me enough to just let me go, give me my little bit of the proceeds and let me split off.” It was a little tit-for-tat, if you’re not going to do this for me, I’m not going to do that for you. I tend to see the others now just for business. It’s a bit daft, actually. That’s why I’m so hot to get these business things over with.

You were hoping to do it today, I gather.

Yeah, there was a little thing . . . you see, each time one of us will get hot for a meeting. Say me, I just got me visa and I got all hot for a meeting. I rang John up, and John was keen to do it. He was going to fly in today from L.A. to New York. Great! I was going to be here; John was going to be here. Then I rang Ringo, and Ringo couldn’t figure out what we were going to actually say, outside of “Hi, there.” And he didn’t want to come all the way to New York from England, he was just getting settled for Christmas. So he was a bit down on it, that kind of blew it out. Then I called John and he said he was talking to George and George was having some kind of visa problems. So it’s a bit difficult to get the four of us together. But it will happen soon.

Lee said that the show you’ll do for Phoenix House as part of the arrangement for your visa will be part of a tour.

The only thing now, obviously, is that it’s dependent on getting a band together. If we can get something together in the early months of 1974, then we’re hoping to come to the States, do a nice tour here. The Phoenix House people helped to get me in. It’s a good cause. We just went down to see one of their branches in East Harlem, just now. It’s fantastic. I wasn’t thinking it would be much, I thought it would be a bit depressing. But it’s a beautiful place. There’s a lot of love in that place. And it’s not the kind of a state thing. There’s discipline, too, but the discipline comes out of love. That way no one minds the discipline. If you just start off with discipline and nothing else, a lot of the kids find it hard to do it. But they’re all very self-supporting now. It’s a great place, I must say. Anyone who’s in trouble with drugs, pills, junk or whatever, should take a look in the Phoenix House.

What was the reaction of the kids when you went in there?

Great. We just shook hands. Their choir sang some songs and we went on a little tour of the house. There was a guy telling us about encounter meetings, how he was putting the bathroom in, doing all the plumbing himself—they’re all very proud, because they’re all people who almost messed up. They just made it, and most of them look like they can really go on to great strength because of it.

Would you like this to be a big proper tour or small, like your university tour?

A big proper tour. I think if you’re coming to the States, you can’t do it funky. I don’t think I could, anyway. I think now I’ll be ready to do a big concert tour, although I find it hard to imagine at the moment.

Now that you’re in New York, I suppose the rumors will start again. There’ll be a Beatles reunion of some sort?

Well, I must say, like as far as getting together as we were, as the Beatles were, I don’t think that’ll ever happen again. I think now everyone’s kind of interested in their little personal things. I kind of like the way we did Band on the Run, the way we did it. Something we’ve never done before, and it’s very interesting. But I do think that I for one am very proud—although I don’t like the word proud, it tends to be—ex-servicemen have used the word . . . if you know what I mean . . . “proud of my country” . . . but I will use the word—I am proud of the Beatle thing. It was great and I can go along with all the people you meet on the street who say you gave so much happiness to many people. I don’t think that’s corny. At the time obviously it just passes over; you don’t really think they mean it. Oh, yeah, sure, and you shake their hand or whatever.

But I dig all that like mad now, and I believe that we did bring a real lot of happiness to the times. So I’m very proud of that kind of stuff and consequently I wouldn’t like to see my past slagged off. So I would like to see more cooperation. . . . if things go right, if things keep cool, I’d like to maybe do some work with them; I’ve got a lot of ideas in my head what I’d like, but I wouldn’t like to tell you before I tell them. We couldn’t be the Beatles-back-together again, but there might be things, little good ventures we could get together on, mutually helpful to all of us and things people would like to see, anyway.

I wouldn’t rule everything out, it’s one of those questions I really have to hedge on. But, I mean, I’m ready. Once we settle our business crap—there was an awfully lot of money made, of course, and none of it came to us, really, in the end. Virtually, that’s the story. So I’d kind of like to salvage some of that and see that not everything’s ripped off.