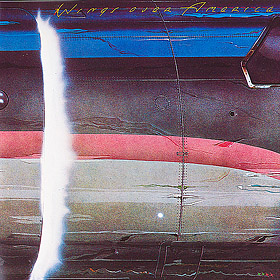

- Album This interview has been made to promote the Wings Over America Official live.

Timeline

More from year 1976

Interviews from the same media

Apr 30, 1970 • From RollingStone

Aug 31, 1972 • From RollingStone

Paul McCartney: The Rolling Stone Interview

Jan 31, 1974 • From RollingStone

Paul McCartney by Paul Gambaccini

Mar 30, 1979 • From RollingStone

Paul McCartney: Ten Days in the Life

Feb 20, 1980 • From RollingStone

Paul McCartney: The Rolling Stone Interview

Sep 11, 1986 • From RollingStone

Jun 15, 1989 • From RollingStone

Paul McCartney: One for the Road

Feb 08, 1990 • From RollingStone

Feb 10, 1994 • From RollingStone

Paul McCartney on 'Beatles 1,' Losing Linda and Being in New York on September 11th

Dec 06, 2001 • From RollingStone

Spread the love! If you like what you are seeing, share it on social networks and let others know about The Paul McCartney Project.

Interview

The interview below has been reproduced from this page . This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

WELL, IT SURE SOUNDS like rock & roll, even if it is Wings. Little Jimmy McCulloch, former Thunderclap Newman, and Denny Laine, former Moody Blue, are burners on guitars. Joe English, former nobody, is ecstatic on blistering drums. Linda McCartney, former photographer, punches away at a stockpile of keyboards and accounts for all the sound effects we’ve grown to love on all the Wings albums. And Paul McCartney, former Beatle, drives the whole band, plus a four-piece horn section adding funk and frills. He cruises on bass while Laine and McCulloch provide the power; on piano, he hammers out “Lady Madonna” and “Live and Let Die”; back on bass, he screams, reaching back for some of that Little Richard inspiration, through “Beware My Love” and “Letting Go.” And after a particularly meaty, beaty number, there is a shout from Laine or McCartney of “rock & roll!”

And Wings gets all the rock & roll responses: people in the audience suddenly sticking their arms up in clenched-fist salutes, piercing the air with two-fingered whistling, whooping in celebration of each of the five Beatles songs offered, unleashing ferocious, match-lit, Bic-flicked encore calls. It is the first American tour by Paul McCartney since 1966, when he was still a you-know-what. Along with John, George and Ringo, he was supposed to have detested the audiences, scream storms of wet panties that rushed them everywhere from Shea Stadium in New York to Candlestick Park in San Francisco. Now, with the Apple rot, Beatles split, lawsuits and bad-mouthings pretty much behind them, Paul finds himself invoking the old days, inviting people to clap hands and stomp feet, waving and posing to audiences behind and to the sides of the stage.

But here in America in 1976, few try rushing the stage; first-aid setups go untested; security guards wind up turning down their walkie-talkies so they can hear the show. The only Beatlemaniacal screaming is at the beginning, when Paul first appears out of the darkness. The one song that gets screeches – an absolute demonstration, in fact – is the quietest Beatle song of all . . .

Saturday, May 8th: on the main floor of the seedy Olympia Stadium in Detroit, Michigan, one young man keeps shouting for the people in front of him to sit down. We were into the acoustic set, with Laine, McCulloch and the McCartneys on rattan chairs, all but Linda playing guitars. After a few numbers, it is Paul alone onstage, tuning up for “Blackbird.” The man in the audience-he apparently saw the first show here the night before – seems to know what’s coming.

“Siddown!” he shrieks. “Siddown, you fuckers!” Then he turns to a friend and explains his urgency. The voice level is down to conversational and he sounds rational.

“I wanna see ‘Yesterday,’ ” he says.

If you want the Beatles, go see Wings.

–George Harrison, November 1974

Paul McCartney doesn’t mind a look back at Yesterday, but today he is dedicated to two goals: the acceptance by public and press of Wings as a band and not as a backup for a former Beatle, and acknowledgment from those same two difficult institutions that Wings (and Paul) are rock, not pop.

But McCartney has some difficulties.

First, he was a Beatle; he can’t change or deny that. And he wouldn’t anyway. “I’m a Beatles fan,” he says later. “When John was saying a couple of years ago that it was all crap, it was all a dream, I know what he was talking about, but at the same time I was sitting there thinking, ‘No it wasn’t.’ It was as much a dream as anything else is; as much crap as anything else is. In fact, it was less crap than a lot of other stuff.” And he agrees with George’s equation of Wings and Beatles:

“I wouldn’t put it just like that. I’d say, ‘If you want the Wings, go see Wings; if you want Beatles, look at an old film.’ But I probably was a little more sort of Beatleminded than the rest. I tended to ring people up and say, ‘Let’s work now,’ ‘Let’s do this.’ So I suppose it’s a fair point that that was my bag anyway and I just continued doing it. Whereas George . . . ’round about Sergeant Pepper, he only did the one track on Sergeant Pepper, he didn’t turn up for a lot of the other stuff, because he really wasn’t that interested. I was still very interested.”

Second difficulty: McCartney is cute. And at age 33, there are none of the signs that make for easy writing – that, say, his face is fuller . . . fleshier . . . rounded out by the years. Backstage, he introduced himself cheerfully as “David Cassidy,” and I could see why. But with few exceptions (if pressed, Peter Frampton and Suzi Quatro come to mind), cute people are not quite believable as pained, ravaged, booze-based, serious rockers.

Another difficulty is that McCartney writes, sings and produces in the pop manner. Not that he wants to. “We’re trying to make it sound as hard as possible,” he says. “But sometimes you just don’t bring off in a studio what you can bring off in a live thing.”

Also, Paul is a family man – married in 1969 to the former Linda Eastman. He doesn’t exactly flaunt her but there she is on the album covers and there she is onstage. The kids (Heather, 13 – by her first marriage – Mary, 6, and Stella, 4) are taken along on most Wings tours, and this one is set up partly around the family situation. The McCartneys, band members and closest aides are in four base cities (Dallas, New York, Chicago and Los Angeles) and commute to and from concerts (31 shows, 21 cities) by private jet. This saves on hotels, airports and general wear and tear, and it keeps the family together. But a photographer on the tour finds the daily commute limiting. “So far,” he says, “I’m shooting an architectural book, mostly buildings. They don’t exactly hang out a lot.”

And, finally, nothing – no new band he can concoct – can compare with the Beatles. This he knows well and, as he patiently counseled a young reporter from NBC-TV: “It may not be the Sixties, but nothing’s the Sixties anymore except the history books. It’s the Seventies and it’s hip and it’s happening. And it’s just . . . enjoy it.”

McCartney and his wife and band have weathered six years of criticism and misunderstanding. They are consoled only by the record buyers and have sold millions of records like “Hi Hi Hi,” “My Love,” “Helen Wheels,” “Jet,” “Band on the Run,” “Junior’s Farm,” “Listen to What the Man Said” and “Letting Go.” Not to mention seven albums, five under the name Wings.

But commercial success – the greatest, most consistent success of any of the former Beatles – is not enough. Paul says he ignores criticism – for every putdown, he says, there’s someone else who loves his stuff. He relishes reminding reporters how critic Richard Goldstein panned Sergeant Pepper. But he is thin-skinned to the point of writing “Silly Love Songs,” an answer to the dismissal of his music as pop puffery. And Linda has long been abused, written off as a particularly successful groupie in her days as a rock photographer in New York’s Village and Fillmore scenes. As a musician and a member of Wings, she has been written off as a particularly successful, etc. . . and she is, you can understand, very defensive.

AT THE SOUND CHECK BEFORE THE first of the two concerts in Detroit, Linda is showing me around her keyboards, instruments she learned to play after marrying McCartney. Atop the electric piano are an ARP synthesizer and a Mini-Moog, which she plays for the opening of “Venus and Mars.” Buttons are labeled “controllers,” “oscillator bank,” “mixer,” “decay time” and “modifiers for attack time.” And if that’s not confusing enough, here, facing the audience, is the Mellotron, which is loaded with tape loops that are activated by depressing keys. There are tapes of Paul singing a line – “Till you go down” – and of a laughing hyena, a pig and a bull. Here, too, is the chorale behind McCulloch’s number, “Medicine Jar,” and the robot/chain saw/moog/drum sound that opens “Silly Love Songs.” And the sounds of frying bacon and chips that appeared on Linda’s “Cook of the House,” her first solo vocal outing on the most recent album, Wings at the Speed of Sound. I mention the criticism that has already built over her celebration of her place in the kitchen. She swivels on her electric piano bench. “My answer,” she says, “is always ‘Fuck off!’ ” She continues, in a weird hybrid of accents from England, New York and finishing school. “Look, we had a great loon in the studios that night. All the hung up people don’t have to buy it, don’t have to listen to it. It’s like having parents on your back, this criticizing. I’ve grown up. I had a great night last night, this is a great band and this is great fun. And that’s all we care about.”

Offstage, heading toward the dressing room, Linda asks that I forget her outburst. But a few minutes later, in conversation with Denny Laine, her hostility wells up again. We are talking about “Silly Love Songs” as a reaction to criticism. “You respond to it,” she says, “but I’d rather have life without it. I had life without it before and found it quite nice. You have criticism in school. When you get out of school, you want to be free.”

Laine adds: “We’re pretty good critics of ourselves. We don’t need all these bums coming along and telling us, “Hey, man . . .’ “

I venture to say that theirs sounds like an insular process, with no room for sounding boards and outside opinions.

“We always know what’s wrong,” says Linda. “We know with every album what’s gone wrong.” During recording sessions, Denny adds, there are friends who drop by and offer thoughts. “So we know pretty well where we stand.”

“We know we’ve got a lot more to do,” Linda says, and turns away to talk with Paul, who’s just returned from the sound check.

Laine speaks with us for a minute more about Wings and the remains of Beatlemania. “The main thing about us,” he says, “is we want to be able to work on the stage without too much adoration, if you know what I mean. We’d rather work for it.” A lot of the audience, he says, still respond out of reverence for a Beatle. “They’re in awe, you know, of Paul. And that’s a bit of a drag.”

SUNDAY, MAY 9TH: PAUL McCARTNEY has just flown into Toronto from New York and sped, in one of the customary five limousines, into the backstage area of the Maple Leaf Gardens. It is 6:20; the show has a scheduled 8 p.m. starting time and he’s been booked into a gold-record presentation with Capitol Records/EMI of Canada, interviews with CBC-TV, two radio stations, one Toronto paper, and ROLLING STONE. And he should have dinner. He is running late. But a rushed sound check in Detroit spoiled the first concert there, and he isn’t about to let it happen again. He steps out of the Fleetwood, looks around, asks the closest person where the stage is and heads off. Dressed in his usual offstage clothing – loud Hawaiian print shirt, tails hanging out of a short leather jacket, unfaded jeans and rubber-soled shoes – he jumps from bass to keyboards to guitars to drums, pumping frantically until he loses a stick. Then he occupies himself behind the sound board to check other mikes and instruments. He works meticulously and by the time he’s finished, it’s 7:20. Capitol and all the interviewers have been waiting since five, but Paul seems positively casual. After a ten-minute break and a huddle with his manager (Brian Brolly, a former MCA executive who joined McCartney in 1974), he signals us into the dressing room for a double-speed interview that takes us up to the minute he has to switch to his stage outfit, a black suit with sequined shoulders. He gnaws at a fried-chicken drumstick, waving his hands expressively and freely to emphasize points.

We begin with Laine’s complaint – about the audience responding more out of awe for Paul than from appreciation of the music.

“I don’t think that’s happening so much now,” he says. “I think that’s what this tour is doing. Maybe they came a bit like that – which can’t be helped – but on this tour, everyone is saying backstage afterward, ‘We came and expected one thing, but it’s very different, really.’ I think you find yourself starting to look at Denny and Jimmy and Linda and Joe and thinking, ‘Well, it’s not what I expected.’

“In the Sixties, or the main Beatle time, there was screaming all the time. And I liked that then because that was that kind of time. I used to feel that that was kind of like a football match. They came just to cheer; the cheering turned into screaming when it translated into young girls. People used to say, ‘Well, isn’t that a drag, ’cause no one listens to your music.’ But some of the time it was good they didn’t because . . . you know, some of the time we were playing pretty rough there, as almost any band from that time will know.” McCartney eases into his answers, gets comfortable, stretches them out, seemingly unconscious of the rush around him.

“I thought when I came out on tour again, it might be very embarrassing if they were listening instead of screaming. David Essex was talking excitedly about the British audience. ‘They’re still screaming, you know.’ Well, for him they are, and that’s his kind of audience, but when we went out, we just got up there and started playing like we were a new group. So everyone just took us like that. Sat there. ‘Yeah, that’s all right.’ And they got up and danced when we did dancing numbers. It’s perfect: you can have your cake and eat it, because they roar when you need them to roar and they listen when you’re hoping they might be listening.”

McCartney opens a fresh pack of cigarettes – the brand, Senior Service – lights up and continues:

“There is this feeling that I should mind if they come to see me as a Beatle. But I really don’t mind. They’re coming to see me; I don’t knock it. It doesn’t matter why they came, it’s what they think when they go home. I don’t know for sure, but I’ve got a feeling that they go away thinking, ‘Oh, well, it’s a band.’ It lets them catch up. I think the press, the media is a bit behind the times, thinking about the Beatles a lot. And I think the kids go away from the show a lot hipper than even the review they’re going to read the next day.”

The press, however, seems to be catching up. On numerous next mornings, reviews have told about the reviewers’ discovery – that Wings is a rock & roll band. The New York Times attended the first show, in Fort Worth, and called it “impressively polished yet vital” and “harder-edged” than expected. Newsweek, apparently forgetting Wings’ six-year stack of golden wax, declared, “Paul McCartney had proved that he could make it on his own.”

“The whole idea behind Wings,” says McCartney, “is to get a touring band. So that we are just like a band, instead of the whole Beatles myth.”

But no matter how much he wants to be just a member of a band, and no matter how good the band is, most of the audience is there to see one man. You can tell by the explosion of strobes and flashes from cameras around the auditorium when the moment occurs that McCartney is by himself on the stage. And by the subsequent explosion set off by people who want to capture the actual moment McCartney is singing “Yesterday.”

Wings is a talented group of musicians, especially with Laine and McCulloch. But the Beatles came to be considered geniuses in the studios. I wonder whether Paul misses the other three as sounding boards. Or were Linda and Denny right in their assertion that they always knew “what’s gone wrong” with every album.

He does miss the Beatles, he says. “I don’t know about the genius bit, but yeah, I think the Beatles was a very equal thing . . . yeah, I used to worry a little more about that, kind of saying to Linda, ‘Look, I know Denny’s good, but he’s not used to me enough. Will I dare offer him this riff; what if he turns it down?’ This standoffishness. But again, you consult your inner oracle and it tells you, well, it’s time that does all of that. You can’t take a baby and make him 14 overnight. Everyone is coming forward a bit more now. So I just thank me lucky stars that I hung in there.”

But democracy, as McCartney knows, has its price. “You’re opening the door to other possibilities, and that’s sort of what broke the Beatles up, really. The freedom for the personalities to do it. I started a group, I’ve got my wife in, took the kids on the road, just because it was all part of the way I feel.”

The McCartney family image does not seem to bother or affect any of the other band members, but McCartney seems sensitive about its effects on Wings’ audience and on the band’s image.

The audience, he says, is “kind of the age group that goes to concerts – kids – and with us it stretches through to older people who were listening to the Beatles and have come right through. And I think we have a bit of a family audience because the way Linda and I live is pretty straight, in a way. So I think people maybe identify who’ve got kids and are bringing them up the same kind of way – sort of liberal, kind of ‘now’ way, rather than . . .” Paul seems momentarily embarrassed. “Sounds terrible, doesn’t it?” he asks.

Surprisingly, the audience is, as Paul notes, pretty much your rock concert crowd, more wheelchairs than baby strollers and not a picnic basket or a leisure suit in sight. And no one seems perturbed that the leader of Wings is not on the loose, the way a Robert Plant or Roger Daltrey or Mick Jagger seem to be. And even if they’re married, they don’t display their wives up onstage with them.

“I used to think of that, when we first got together, had Linda in the group. ‘Oh, oh, we’ve had it with the groupies now! Everyone’s gonna think we’re real old squares – blimey! Married! God, at least we could have just lived together or something – that would have been a bit hip.’ Then you realize it doesn’t matter. They really come for the music. At first it did seem funny to be up there with a wife instead of just friends or people associated with the game. But I think the nice thing that’s happened is it seems to be part of a trend anyway, where women are getting in a bit more, families are a bit cooler than they were, Things change.

“And the show doesn’t have anything that’s ‘family.’ I mean, I kissed Linda onstage the other night, and for me, that’s kind of, ‘Wow, I must be getting real relaxed,’ ’cause I can’t do that in public, normally. I’m a bit kinda shy.”

It is past eight now; the show, it was decided, would start around 8:30. Capitol and local press are still waiting. Paul waves all that aside with a hand. He had told a publicist that he wanted to do this interview right.

Being a family man, he is saying now, has not affected his songwriting. McCartney, after all, was always the softer, poppier side of the Beatles. “I still think basically the same kind of things I used to; the only difference is I’ll do a tune like ‘Mary Had a Little Lamb’ [an early Wings single], but that’s the kind of thing kids request. Limitations? Maybe. The only kind I can think of is not wanting to be maybe too . . . far out. But I write songs basically the same way, which is any way. It’s mainly just when I’ve got a minute, but that can come in any different form. Just sit around . . . if I feel like playing my guitar, a song comes out. That’s the same as it’s always been.”

Onstage, Linda McCartney stays discreetly in the shadows, behind her keyboards, for the first few numbers, leaving Paul looking unattached at least for a while. When he introduces her as “my better half,” she gets a roar of approval. In Detroit, with Paul on piano, she steps up to a vocal mike in front of the keyboards only after the 19th song has passed. Number 20 is “My Love,” and she places her hands, rather dramatically, on her hips, as if to show the crowd justwho “does it good.” But for the most part, she is there to lend able support to the band. And she has developed into a capable backup vocalist, and a spirited rock & roll cheerleader.

WINGS IS A POP MACHINE that has produced five albums in five years, with singles filling in the occasional lags. And now, as McCartney had hoped before the most recent personnel were affixed, it is a traveling band as well, with annual U.S. tours a real possibility. As such, there is less time for other projects but McCartney is still hoping to do the songs and score for a full-length animation film of Rupert, a British cartoon character. Rupert, McCartney explained, is a bear. “I like Walt Disney cartoons,” he says. “They sort of live forever.”

Rupert the bear is not exactly Yellow Submarine, in which, you remember, the Fab Four took on the Blue Meanies in defense of good old Pepperland and what it stood for: music, beauty and color. And some other stuff. Without getting into what the real-life Beatles seemed to stand for, one wonders what McCartney stands for today.

“Same goals exactly,” he says, with no hesitation. “It is still peace and light.”

A year and a winter ago, another former Beatle went on tour and, to put it mildly, flopped. George Harrison had maturity, sincerity and the best intentions on his side. He appreciated the Beatles and his role in the phenomenon, he said, but he had grown up, changed, and did not care to dwell in the past. And to let everyone know how firmly he felt, he did a two-and-a-half-hour show dominated by Indian music. He did four Beatles songs, and this only after active encouragement from fellow musicians on the tour. He changed lyrics in three of the four Beatles songs, and rearrangements (along with George’s overworked, hoarse voice) turned them into hardly reasonable facsimiles of the songs many in the audiences had wanted to hear.

Paul and Linda attended Harrison’s Madison Square Garden show, Paul disguised in Afro wig, shades and walrus mustache, “and we loved it,” he says. He agrees that George had the right, at whatever critical cost, to say, “This is me, now.”

People, says McCartney, have this . . . attitude about the Beatles. “There was some girl on holiday and we were talking to her. She’s a real average British girl and she sort of summed up her view of the Beatles: these lads from Liverpool, lovely, cheery and singing lovely songs . . . and then, drugs! And they all went crazy on drugs. And that was the end of the story for her. Well, that’s kind of silly. And I think there’s a lot of people approaching the new shows like that. ‘Oh, well, can they actually stand up there when they were once the Beatles.’ You just have to say, ‘Well, this is me now, sorry, folks.’ Sergeant Pepper‘s a big change from the record before it. That was us then. So I think George is just taking it very naturally and saying, ‘This is me.’ “

McCartney has said he doesn’t want to get into criticizing Harrison, but the producer in him finally wins out: “If I’d been producing him and if I’d been his impresario on that tour,” he says, “I would have asked him to do a few more songs he was known for. And also to stick to the arrangement a little bit.” McCartney puts on a good-natured look. “To which he’d probably say, ‘Piss off,’ and good luck to him.”

But, he adds, “I can see his attitude totally.” On the first Wings tours – a limited, bus-hopping affair to British universities in 1972, a larger European swing in ’73 – “We did the same thing; just no Beatles whatsoever. I’ll tell you the truth: it was too painful. It was too much of a trauma. It was like reliving a sort of a weird dream, doing a Beatles tune. One of the guys promoting us on that European tour said, ‘At the end, you should just come on with a guitar and do “Yesterday.” ‘I thought, ‘Oh God, I couldn’t face it.’ Because there was a lot of rubbish on, you know. We were into fighting for a while, we were being poisoned against each other by various people, mainly by one man who shall remain anonymous.”

The man, of course, was Allen Klein, who became manager of John, George and Ringo in May 1969, over McCartney’s protests. As tension in the studios mounted, as Apple teetered, and as Ringo, John and Paul announced separate threats to split, McCartney suspected Klein of taking more than his share of Apple’s money. In spring 1970, in order to take action against Klein, he was forced to sue Apple – and the other Beatles themselves – for dissolution of the group. After several difficult years, the years of the rubbish, Lennon, Harrison and Starr, along with others involved in Apple, filed suit in London against Klein, for “fraud,” for taking “excessive commissions” and for “otherwise mismanag[ing]” his clients. Klein turned around and filed a suit, in New York, against the three ex-Beatles, Yoko Ono and Apple for more than $63 million in damages and future earnings; Klein enjoined McCartney as part of a “conspiracy” to damage or injure him and his company, seeking damages of $34 million plus interest. The London case against Klein is scheduled to go to court next January.

McCartney hopes to steer clear of the trial, he says, but will cooperate with testimony – “anything that can help. I just want everyone’s head to be clear, to get on with what they do.” Klein’s countersuit, McCartney says, “is an old manager’s trick; the best form of defense being attack. It’s ridiculous what he’s doing. Even for himself. He should just get on with his business and think, ‘Well, Christ, I got the Stones’ old masters, I got this’ – he had a half million out of the company, so he’s had a bit, you know. But he’s just trying to hang in there, to prove a point. It’s a bit … to me it’s very like the Nixon thing, of ‘I said I was a goodie and I’m damn well going to prove it.’ “

With the pressures between him and the others off, McCartney found the songs coming back. “You think, well, they’re great tunes, I like the tunes. When we played them we’d get a bit nostalgic, think, ‘Oh, this is nice, isn’t it.’ So I just decided in the end, this wasn’t such a big deal. I’d do them.”

McCartney, in fact, is doing only one more Beatles song than George did on his tour. He, too, wanted to play down the Beatle identity (the tour is billed “Wings over America” and McCartney’s name does not appear on tickets or advertising). He selected the songs at random, he says, rejecting “Hey Jude” as a closer simply because “it didn’t feel right,” and choosing instead a song played on previous tours but never recorded, an all-out jam rocker called “Soily.”

But the difference between Harrison and McCartney is in the faithfulness of Paul’s arrangements, so that the horn section does a credible impression of a cello on “Yesterday,” and “Lady Madonna” is churned out happily, and “The Long and Winding Road” and “Blackbird” are almost straight off the records. Only on “I’ve Just Seen a Face,” played on amplified 12-string Ovation guitar, with the McCartneys’ and Laine’s voices blending together in a folky, Rooftop Singers style, does he wander.

In Toronto, there was a rash of reunion rumors. By show time, scalpers outside were happily selling their tickets for $50 and $60 apiece, while inside, film crews from as far away as London had their cameras hoisted and ready. From the first show in Texas, there had been talk that the once-again-friendly Beatles might do a friendly number together. In New York, where Lennon lives, similar talk persists. And in London, “Yesterday,” the single, leads a pack of two dozen Beatles reissues invading the pop charts.

McCartney is pleased about “Yesterday.” “It happens to coincide, luckily for us. It’s bringing it to people’s ears. That’s the main thing, really, ’cause if you’re not in with a single or record, people just tend to forget.” He is not wary of an acetate Beatlemania leading to even more fervent calls for a reunion.

“We maybe could be together for a thing but it always feels to me like it would be a bit limp.” In response to an American promoter’s offer of between $30 and $50 million for one Beatles concert, McCartney told a reporter that he would not participate in a reunion purely for money. Now, in Toronto, he is qualifying that remark.

“The truth is very ordinary. The truth is just that since we split up, we’ve not seen much of each other. We visit occasionally, we’re still friends, but we don’t feel like getting up and playing again. You can’t tell that to people. You say that and they say, ‘How about this money, then?’ ‘Or how about this?’ And you end up having to think of reasons why you don’t feel like it. And, of course, any one of them taken on its own isn’t really true, but I was just stuck for an answer, so I said I wouldn’t do it just for the money anyway. And I saw John last time, he says, ‘I agreed with that.’ But there’s a million other points in there. A whole million angles.

“I tell you, before this tour, I was tempted to ring everyone up and say, ‘Look, is it true we’re not going to get back together, ’cause we all pretty much feel like we’re not. And as long as I could get everyone to say, ‘No, we’re definitely not,’ then I could say ‘It’s a definite no-no.’ But I know my feeling, and I think the others’ feeling, in a way, is we don’t want to close the door to anything in the future. We might like it someday.

“Again, talking to John before the tour, I’m saying to him, ‘Well, are you coming to the show at Madison Square?’ ‘Well,’ he says, ‘Everyone’s kind of asking me, “Am I going?” Should I go?’ And I’m saying, ‘Oh, god, that’s a drag, isn’t it. You just can’t even come out and see our show.’ So there are these other involvements. If anyone comes, they feel like they’ve got to get up. Then they get up, we’ve got to be good. Can’t just get up and be crummy, ’cause then they say, ‘The Beatles really blew it on the Wings tour,’ or something. So, but you see how long I’ve taken just to answer this question. God, it goes on forever. So you can see why I just wanted to say no.”

And yet, McCartney just cannot close the door.

“We’ve left it,” he says, “if John feels like coming out that evening, great, we’ll try and get him in. Have it all cool, no big numbers. We’ll just play it by ear.”

The Wings concert is a little contrived – not unlike, say, a Wings album – but I like artists who get out there and entertain. With a lot of help from Showco, the Dallas-based sound-and-light company, McCartney has fashioned a show that reminds of Elton John – especially when Paul’s busying himself behind the Steinway – and has touches of the Who, David Bowie and Led Zeppelin. In fact, McCartney discovered Showco at a Led Zeppelin concert in Earls Court in London; he was impressed with how they managed to fill the 35,000-seat hall with crisp sound.

For Wings, Showco has provided touches like “flying monitors”–monitor speakers hung from beams instead of placed on the stage floor, between musicians and audience–and a black plexiglass stage with platforms that illuminate in a tangerine glow, surrounded by dancing yellow bulbs, for the music-hall number, “You Gave Me the Answer.” The laser machine from the last Who tour is here, projecting green beams against smoke from a pair of insect foggers for the last song, “Soily.”

The emotional high point of the concert, of course, is “Yesterday,” but the showstopper is “Live and Let Die,” the song McCartney wrote for a James Bond film. In concert, Wings attacks the audience with powder kegs, strobes, smoke, syncopated spotlights, and the laser machine gunning string beams of light from back of the stage to the opposite end of the hall. And the music – teasing, then exploding into rat-a-tat violence – fully warrants the effects.

For “Band on the Run,” the last number before the encore call, a film of the shooting of the album cover is projected onto a movie screen; behind other songs, paintings – and one cartoon – appear on another screen, behind the band. The paintings, McCartney says, are by Magritte and David Hockney; the etchings of Magneto and Titaniun Man are by Marvel Comics. “It’s all art,” says the Beatle.

Before the tour, the best guesses had Wings grossing $4.5 million for 28 shows in 20 cities. Since then, a huge show has been added in Seattle – at the 60,000-capacity King Dome – and additional concerts have been added in Los Angeles and Chicago. The gross should be over $5 million, roughly a million more than the Harrison tour. But the net should be another story, given the lavishness of the stage show, the size of the entourage (17 with Showco, nine-piece band, family, friends, publicists, manager, security and various other aides) and the private Braniff-leased Bac 1011 jet that flies the band back to a base city after every concert – not to mention a mess of Wings memorabilia. Out in the lobbies, fans can pick up a T-shirt, a program and a poster. But backstage, for the touring party, there are Wings jackets, T-shirts from all the different tours, badges, pins, patches and medallions. Linda wears jeans with “Wings” embroidered on a back pocket; she and Paul wear matching ivory wings on necklaces. And the crew drinks from Wings paper cups.

The in-group level of a kind of Wingsmania is furthered by the chronicling of this tour: concerts are being recorded for a possible album, filmed for a possible movie, photographed separately by two cameramen for the press and a possible book, and sketched, courtroom-artist style, for possible future paintings or inclusion in another possible book.

But all these projects, McCartney says, aren’t even that probable. “It’s all ‘in case.’ ” In case some day he wants a film, a photo, a record, even a sketch of the first Wings American tour. It’s nice to look back.

It is 8:30 now, the Wings are all in costume and they should be onstage by now. They are instead in an upstairs room backstage. Here, they manage to oblige the executives of Capitol Records/EMI of Canada, shake hands all around, accept six gold and platinum albums, pose for photographs, have a laugh or two and apologize for having to run – all within three minutes. But everybody, in the end, is happy.

The local interviewers are still afloat; they’ve been informed that after the show Wings have to make a quick getaway because their jet has to be off the runway by midnight, to comply with a noise-abatement ordinance. So they are not planning to get any time with McCartney.

But after the concert, with Showco breaking down the light-stands, the sound system and the stage, with band members, security guards, aides, photographers and the sketch artist all scurrying around, and with the five Fleet-woods already warmed up and purring, Brian Brolly, the manager, gathers up the local reporters and hustles them into the dressing room, apologizing all the way. They will have just about two hot minutes.

McCartney, back in street clothes, greets them, looking relaxed and interested. He apparently wants to do this right, too. He shows them a painting a friend has done of him and Linda and they proceed to field a dozen questions, about musical roots, the first time Linda saw Paul (Beatles, Shea Stadium, 1966) and, of course, the rumors about the Toronto Beatles reunion. Brolly gets itchy and clears his throat and the room all at once, and the McCartneys scram into their limo and screech away.

Outside, a knot of the faithful wave to them and come up with a modified ovation. It is not exactly Wingsmania, and it is by no means Beatlemania. But it sure seems like rock & roll.

Last updated on March 7, 2019

Contribute!

Have you spotted an error on the page? Do you want to suggest new content? Or do you simply want to leave a comment ? Please use the form below!

I wish Paul would play my song, "Does Your Mama Stop at Stop Signs!" It's on YouTube