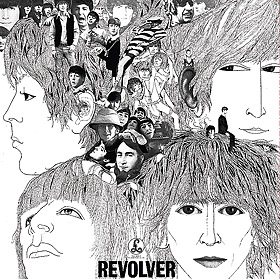

- Album This song officially appears on the Revolver (UK Mono) LP.

Related sessions

This song has been recorded during the following studio sessions

Circa 2022

Spread the love! If you like what you are seeing, share it on social networks and let others know about The Paul McCartney Project.

Song facts

This track proved very difficult for us to learn. I kept on getting it wrong, because it was written in a very odd way. It wasn’t four-four or waltz time or anything. Then I realised that it was regularly irregular, and, after that, we soon worked it out.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles: Off The Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

From Wikipedia:

“I Want to Tell You” is a song by the English rock band the Beatles from their 1966 album Revolver. It was written and sung by George Harrison, the band’s lead guitarist. After “Taxman” and “Love You To“, it was the third Harrison composition recorded for Revolver. Its inclusion on the LP marked the first time that he was allocated more than two songs on a Beatles album, a reflection of his continued growth as a songwriter beside John Lennon and Paul McCartney.

When writing “I Want to Tell You”, Harrison drew inspiration from his experimentation with the hallucinogenic drug LSD. The lyrics address what he later termed “the avalanche of thoughts that are so hard to write down or say or transmit”. In combination with the song’s philosophical message, Harrison’s stuttering guitar riff and the dissonance he employs in the melody reflect the difficulties of achieving meaningful communication. The recording marked the first time that McCartney played his bass guitar part after the band had completed the rhythm track for a song, a technique that became commonplace on the Beatles’ subsequent recordings.

Among music critics and Beatles biographers, many writers have admired the group’s performance on the track, particularly McCartney’s use of Indian-style vocal melisma. Harrison performed “I Want to Tell You” as the opening song throughout his 1991 Japanese tour with Eric Clapton. A version recorded during that tour appears on his Live in Japan album. At the Concert for George tribute in November 2002, a year after Harrison’s death, the song was used to open the Western portion of the event, when it was performed by Jeff Lynne. Ted Nugent, the Smithereens, Thea Gilmore and the Melvins are among the other artists who have covered the track.

Background and inspiration

George Harrison wrote “I Want to Tell You” in the early part of 1966, the year in which his songwriting matured in terms of subject matter and productivity. As a secondary composer to John Lennon and Paul McCartney in the Beatles, Harrison began to establish his own musical identity through his absorption in Indian culture, as well as the perspective he gained through his experiences with the hallucinogenic drug lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). According to author Gary Tillery, the song resulted from a “creative surge” that Harrison experienced at the start of 1966. During the same period, the Beatles had been afforded an unusually long time free of professional commitments due to their decision to turn down A Talent for Loving as their third film for United Artists. Harrison used this time to study the Indian sitar and, like Lennon, to explore philosophical issues in his songwriting while preparing to record the band’s next album, Revolver.

In his autobiography, I, Me, Mine, Harrison says that “I Want to Tell You” addresses “the avalanche of thoughts that are so hard to write down or say or transmit”. Authors Russell Reising and Jim LeBlanc cite the song, along with “Rain” and “Within You Without You“, as an early example of the Beatles abandoning “coy” statements in their lyrics and instead “adopt[ing] an urgent tone, intent on channeling some essential knowledge, the psychological and/or philosophical epiphanies of LSD experience” to their listeners. Writing in The Beatles Anthology, Harrison likened the outlook inspired by his taking the drug to that of “an astronaut on the moon, or in his spaceship, looking back at the Earth. I was looking back to the Earth from my awareness.”

Author Robert Rodriguez views the song as reflecting the effects of Harrison’s search for increased awareness, in that “the faster and more wide-reaching his thoughts came, the greater the struggle to find the words to express them”. As reproduced in I, Me, Mine, Harrison’s original lyrics were more direct and personal, compared with the philosophical focus of the completed song. The latter has nevertheless invited interpretation as a standard love song, in which the singer is cautiously entering into a romance. Another interpretation is that the theme of miscommunication was a statement on the Beatles’ divergence from their audience, during a time when the group had tired of performing concerts before screaming fans.

Composition – Music

“I Want to Tell You” is in the key of A major and in a standard time signature of 4/4. It contains a low-register, descending guitar riff that music journalist Richie Unterberger describes as “circular, full” and “typical of 1966 British mod rock”. The riff opens and closes the song and recurs between the verses. Particularly over the introduction, the rests between the riff’s syncopated notes create a stammering effect. The metric anomalies suggested by this effect are borne out further in the uneven, eleven-bar length of the verse. The main portion of the song consists of two verses, a bridge (or middle eight), followed by a verse, a second bridge and the final verse.

According to Rodriguez, “I Want to Tell You” is an early example of Harrison “matching the music to the message”, as aspects of the song’s rhythm, harmony and structure combine to convey the difficulties in achieving meaningful communication. As in his 1965 composition “Think for Yourself“, Harrison’s choice of chords reflects his interest in harmonic expressivity. The verse opens with a harmonious E-A-B-C#-E melody-note progression over an A major chord, after which the melody begins a harsh ascent with a move to the II7 (B7) chord. Further to the off-kilter quality of the opening riff, musicologist Alan Pollack identifies this chord change as part of the disorientating characteristics of the verses, due to the change occurring midway through the fourth bar, rather than at the start of the measure. The musical and emotional dissonance is then heightened by the use of E7♭9, a chord that Harrison said he happened upon while striving for a sound that adequately conveyed a sense of frustration. With the return to the I chord for the guitar riff, the harmonic progression through the verse suggests what author Ian MacDonald terms “an Oriental variant of the A major scale” that is “more Arabic than Indian”.

The middle eight sections present a softer harmonic content relative to the strident progression over the verses. The melody encompasses B minor, diminished and major 7 chords, together with A major. The inner voicings within this chord pattern produce a chromatic descent of notes through each semitone from F♯ to C♯. Musicologist Walter Everett comments on the aptness of the conciliatory lyric “Maybe you’d understand”, which closes the second of these sections, as the melody concludes on a perfect authentic cadence, representing in musical terms “a natural emblem for any coming together”.

Pollack views the song’s outro as partly a reprise of the introduction and partly a departure in the form of “a one-two-three-go! style of fade-out ending”. On the Beatles’ recording, the group vocals over this section include Indian-style gamaks (performed by McCartney) on the word “time”, creating a melisma effect that is also present on Harrison’s Revolver track “Love You To” and on Lennon’s “Rain”. Further to Harrison’s drawn-out phrasing over the first line of the verses, this detail demonstrates the composition’s subtle Indian influence.

Composition – Lyrics

The lyrics to “I Want to Tell You” address problems in communication and the inadequacy of words in conveying genuine emotion. Writing in 1969, author Dave Laing identified “serene desperation” in the song’s “attempt at real total contact in any interpersonal context”. Author Ian Inglis notes that lines such as “My head is filled with things to say” and “The games begin to drag me down” present in modern-day terms the same concepts regarding interpersonal barriers with which philosophers have struggled since the pre-Socratic period.

MacDonald cites the lyrics to the first bridge – “But if I seem to act unkind / It’s only me, it’s not my mind / That is confusing things” – as an example of Harrison applying an Eastern philosophical approach to difficulties in communication, by presenting them as “contradictions between different levels of being”. In Laing’s interpretation, the entities “me” and “my mind” represent, respectively, “individualistic, selfish ego” and “the Buddhist not-self, freed from the anxieties of historical Time”. In I, Me, Mine, however, Harrison states that, with hindsight, the order of “me” and “my mind” should be reversed, since: “The mind is the thing that hops about telling us to do this and do that – when what we need is to lose (forget) the mind.”

Further to Laing’s reading of the song’s message, author and critic Tim Riley deems the barriers in communication to be the boundaries imposed by the anxious, Western concept of time, as Harrison instead “seeks healthy exchange and the enlightened possibilities” offered outside such limitations. According to Riley, “the transcendental key” is therefore the song’s concluding lines – “I don’t mind / I could wait forever, I’ve got time” – signifying the singer’s release from vexation and temporal restrictions.

Recording

Untitled at the time, “I Want to Tell You” was the third Harrison composition that the Beatles recorded for Revolver, although his initial submission for a third contribution was “Isn’t It a Pity”. It was the first time he had been permitted more than two songs on one of the group’s albums. The opportunity came about due to Lennon’s inability to write any new material over the previous weeks. Exasperated by Harrison’s habit of not titling his compositions, Lennon jokingly named it “Granny Smith Part Friggin’ Two” – referring to the working title, derived from the Granny Smith apple, for “Love You To”. Following Lennon’s remark, Geoff Emerick, the Beatles’ recording engineer, named the new song “Laxton’s Superb” after another variety of apple.

The Beatles taped the main track, consisting of guitars, piano and drums, at EMI Studios (now Abbey Road Studios) in London. The session took place on 2 June 1966, the day after Harrison met Indian classical musician Ravi Shankar for the first time and secured Shankar’s agreement to help him master the sitar. The band recorded five takes of the song before Harrison selected the third of these for further work. After reduction to a single track on the four-track master tape, their performance consisted of Harrison on lead guitar, treated with a Leslie effect, McCartney on piano and Ringo Starr on drums, with Lennon adding tambourine. The group then overdubbed vocals, with McCartney and Lennon singing parallel harmony parts beside Harrison’s lead vocal. Further overdubs included maracas, the sound of which Pollack likens to a rattlesnake; additional piano, at the end of the bridge sections and over the E7♭9 chord in the verses; and handclaps.

Created during a period when the Beatles had fully embraced the recording studio as a means of artistic expression, the recording added further to the message behind the song. Like “Eight Days a Week“, the completed track begins with a fade-in, a device that in combination with the fadeout, according to Rodriguez, “provided a circular effect, perfectly matching the song’s lack of resolution”. Everett similarly recognises McCartney’s “clumsy finger-tapping impatience” on the piano over the E7♭9 chord as an apt expression of the struggle to articulate.

The final overdub was McCartney’s bass guitar part, which he added on 3 June. The process of recording the bass separately from a rhythm track provided greater flexibility when mixing a song, and allowed McCartney to control the harmonic structure of the music by defining chords. As confirmed by the band’s recording historian, Mark Lewisohn, “I Want to Tell You” was the first Beatles song to have the bass superimposed onto a dedicated track on the recording. This technique became commonplace in the Beatles’ subsequent work. During the 3 June session, the song was temporarily renamed “I Don’t Know”, which had been Harrison’s reply to a question from producer George Martin as to what he wanted to call the track. The eventual title was decided on by 6 June, during a remixing and tape-copying session for the album.

Release and reception

EMI’s Parlophone label released Revolver on 5 August 1966, one week before the Beatles began their final North American tour. “I Want to Tell You” was sequenced on side two of the LP between Lennon’s song about a New York doctor who administered amphetamine doses to his wealthy patients, “Doctor Robert“, and “Got to Get You into My Life“, which McCartney said he wrote as “an ode to pot”. For the North American version of Revolver, however, Capitol Records omitted “Doctor Robert”, together with two other Lennon-written tracks; as a result, the eleven-song US release reinforced the level of contribution from McCartney and from Harrison.

According to Beatles biographer Nicholas Schaffner, Harrison’s Revolver compositions – “Taxman“, which opened the album, the Indian music-styled “Love You To”, and “I Want to Tell You” – established him as a songwriter within the band. Recalling the release in the 2004 edition of The Rolling Stone Album Guide, Rob Sheffield said that Revolver displayed a diversity of emotions and styles ranging from the Beatles’ “prettiest music” to “their scariest”, among which “I Want to Tell You” represented the band at “their friendliest”. Commenting on the unprecedented inclusion of three of his songs on a Beatles album, Harrison told Melody Maker in 1966 that he felt disadvantaged in not having a collaborator, as Lennon and McCartney were to one another. He added: “when you’re competing against John and Paul, you have to be very good to even get in the same league.”

Melody Maker‘s album reviewer wrote that “The Beatles’ individual personalities are now showing through loud and clear” and he admired the song’s combination of guitar and piano motifs and vocal harmonies. In their joint review in Record Mirror, Richard Green found the track “Well-written, produced and sung” and praised the harmony singing, while Peter Jones commented on the effectiveness of the introduction and concluded: “The deliberately off-key sounds in the backing are again very distinctive. Adds something to a toughly romantic number.” Maureen Cleave of The Evening Standard expressed surprise that Harrison had written two of the album’s best tracks, in “Taxman” and “I Want to Tell You”, and described the latter as a “fine love song”.

In America, due to the controversy there surrounding Lennon’s remark that the Beatles had become more popular than Christianity, the initial reviews of Revolver were relatively lukewarm. While commenting on this phenomenon in September 1966, KRLA Beat‘s reviewer described “I Want to Tell You” as “unusual, newly-melodic, and interesting” and lamented that, as with songs such as “She Said She Said” and “Yellow Submarine“, it was being denied the recognition it deserved.

Retrospective assessment and legacy

Writing in Rolling Stone‘s Harrison commemorative issue, in January 2002, Mikal Gilmore recognised his incorporation of dissonance on “I Want to Tell You” as having been “revolutionary in popular music” in 1966. Gilmore considered this innovation to be “perhaps more originally creative” than the avant-garde styling that Lennon and McCartney took from Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luciano Berio, Edgar Varese and Igor Stravinsky and incorporated into the Beatles’ work over the same period. According to musicologist Dominic Pedler, the E7♭9 chord that Harrison introduced in the song became “one of the most legendary in the entire Beatles catalogue”. Speaking in 2001, Harrison said: “I’m really proud of that as I literally invented that chord … John later borrowed it on I Want You (She’s So Heavy): [over the line] ‘It’s driving me mad.'”

In his overview of “I Want to Tell You”, Alan Pollack highlights Harrison’s descending guitar riff as “one of those all-time great ostinato patterns that sets the tone of the whole song right from the start”. Producer and musician Chip Douglas has stated that he based the guitar riff for the Monkees’ 1967 hit “Pleasant Valley Sunday” on that of the Beatles’ song. Neil Innes of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band (and later the Rutles) recalls being at Abbey Road Studios while the Beatles were recording “I Want to Tell You” and his band were working on a 1920s vaudeville song titled “My Brother Makes the Noises for the Talkies”. Innes said he heard the Beatles playing back “I Want to Tell You” at full volume and appreciated then, in the words of music journalist Robert Fontenot, “just how far out of their league he was, creatively”. Innes has since included his recollection of this episode in his stage show.

Among Beatles biographers, Ian MacDonald cites the song as an example of Harrison’s standing as “[if] not the most talented then certainly the most thoughtful of the songwriting Beatles”. He comments that, in keeping with the lyrics’ subtle Hindu-aligned perspective, Harrison’s embrace of Indian philosophy “was dominating the social life of the group” a year after its release. Jonathan Gould considers that the track would have been a highlight of any Beatles album before Revolver but, such was the standard of songwriting on their 1966 album, it “gets lost in the shuffle of Lennon and McCartney tunes on side two”. Simon Leng writes that, aided by the “fertile harmonic imagination” evident in “I Want to Tell You”, Revolver “changed George Harrison’s musical identity for good”, presenting him in a multitude of roles: “a guitarist, a singer, a world music innovator … [and] a songwriter”.

In his review of the song for AllMusic, Richie Unterberger admires its “interesting, idiosyncratic qualities” and the group vocals on the recording, adding that McCartney’s singing merits him recognition as “one of the great upper-register male harmony singers in rock”. Similarly impressed with McCartney’s contribution, Joe Bosso of MusicRadar describes the incorporation of vocal melisma as “an affectionate nod to Harrison’s Indian influences” and includes the track among his choice of Harrison’s ten best songs from the Beatles era. In a 2009 review of Revolver, Chris Coplan of Consequence of Sound said that Harrison’s presence as a third vocalist “fits perfectly in contrast with some of the bigger aspects of the [album’s] psychedelic sounds”, and added: “In a song like ‘I Want To Tell You’, the sinister piano and the steady, near-tribal drum line combine effortlessly with his voice to make for a song that is as beautiful as it is emotionally impacting and disturbing.” […]

I asked George whether he was more confident in his songwriting.

Naturally. You get more confident as you progress. In the old days, I used to say to myself, ‘I’m sure I can write’, but it was difficult because of John and Paul. Their standard of writing has bettered over the years, so it was very hard for me to come straight to the top — on par with them, instead of building up like they did.

Did you go to John and Paul for advice? I asked.

They gave me an awful lot of encouragement. Their reaction has been very good — if it hadn’t I think I would have crawled away. Now I know what it’s all about, my songs have come more into perspective. All of them are very simple, but simplicity to me may seem very complex to others. I’ve thrown away about thirty songs, they may have been alright if I’d worked on them, but I didn’t think they were strong enough. My main trouble is the lyrics. I can’t seem to write down what I want to say — it doesn’t come over literally, so I compromise, usually far too much I suppose. I find that everything makes a song, not just the melody as so many people seem to think. but the words, the technique — the lot.

George Harrison – From The Beatles Monthly Book, October 1966

From The Usenet Guide to Beatles Recording Variations:

[a] mono 3 Jun 1966.

UK: Parlophone PMC 7009 Revolver 1966.

US: Capitol T 2576 Revolver 1966.[b] stereo 21 Jun 1966.

UK: Parlophone PCS 7009 Revolver 1966.

US: Capitol ST 2576 Revolver 1966.

CD: EMI CDP 7 46441 2 Revolver 1987.The piano comes through more noticeably in mono.

Last updated on November 14, 2023

Lyrics

I want to tell you

My head is filled with things to say

When you're here

All those words they seem to slip away

When I get near you

The games begin to drag me down

It's all right

I'll make you maybe next time around

But if I seem to act unkind

It's only me, it's not my mind

That is confusing things

I want to tell you

I feel hung up and I don't know why

I don't mind

I could wait forever, I've got time

Sometimes I wish I knew you well

Then I could speak my mind and tell

Maybe you'd understand

Variations

Officially appears on

LP • Released in 1966

2:28 • Studio version • A • Mono

- Paul McCartney :

- Backing vocals, Bass, Handclaps, Piano

- Ringo Starr :

- Drums, Handclaps, Maracas

- John Lennon :

- Backing vocals, Handclaps, Tambourine

- George Harrison :

- Handclaps, Lead guitar, Lead vocals

- George Martin :

- Producer

- Geoff Emerick :

- Recording engineer

- Session Recording:

- Jun 02, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Overdubs:

- Jun 03, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Mixing:

- Jun 03, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

LP • Released in 1966

2:28 • Studio version • B • Stereo

- Paul McCartney :

- Backing vocals, Bass, Handclaps, Piano

- Ringo Starr :

- Drums, Handclaps, Maracas

- John Lennon :

- Backing vocals, Handclaps, Tambourine

- George Harrison :

- Handclaps, Lead guitar, Lead vocals

- George Martin :

- Producer

- Geoff Emerick :

- Recording engineer

- Session Recording:

- Jun 02, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Overdubs:

- Jun 03, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Mixing:

- Jun 21, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Revolver (UK Mono - first pressing)

LP • Released in 1966

2:28 • Studio version • A • Mono

- Paul McCartney :

- Backing vocals, Bass, Handclaps, Piano

- Ringo Starr :

- Drums, Handclaps, Maracas

- John Lennon :

- Backing vocals, Handclaps, Tambourine

- George Harrison :

- Handclaps, Lead guitar, Lead vocals

- George Martin :

- Producer

- Geoff Emerick :

- Recording engineer

- Session Recording:

- Jun 02, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Overdubs:

- Jun 03, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Mixing:

- Jun 03, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

LP • Released in 1966

2:28 • Studio version • A • Mono

- Paul McCartney :

- Backing vocals, Bass, Handclaps, Piano

- Ringo Starr :

- Drums, Handclaps, Maracas

- John Lennon :

- Backing vocals, Handclaps, Tambourine

- George Harrison :

- Handclaps, Lead guitar, Lead vocals

- George Martin :

- Producer

- Geoff Emerick :

- Recording engineer

- Session Recording:

- Jun 02, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Overdubs:

- Jun 03, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Mixing:

- Jun 03, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

LP • Released in 1966

2:28 • Studio version • B • Stereo

- Paul McCartney :

- Backing vocals, Bass, Handclaps, Piano

- Ringo Starr :

- Drums, Handclaps, Maracas

- John Lennon :

- Backing vocals, Handclaps, Tambourine

- George Harrison :

- Handclaps, Lead guitar, Lead vocals

- George Martin :

- Producer

- Geoff Emerick :

- Recording engineer

- Session Recording:

- Jun 02, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Overdubs:

- Jun 03, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Mixing:

- Jun 21, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Revolver (Mono - 2009 remaster)

Official album • Released in 2009

2:28 • Studio version • A2009 • Mono • 2009 mono remaster

- Paul McCartney :

- Backing vocals, Bass, Handclaps, Piano

- Ringo Starr :

- Drums, Handclaps, Maracas

- John Lennon :

- Backing vocals, Handclaps, Tambourine

- George Harrison :

- Handclaps, Lead guitar, Lead vocals

- George Martin :

- Producer

- Geoff Emerick :

- Recording engineer

- Paul Hicks :

- Remastering

- Guy Massey :

- Remastering

- Sean Magee :

- Remastering

- Allan Rouse :

- Project co-ordinator

- Session Recording:

- Jun 02, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Overdubs:

- Jun 03, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Mixing:

- Jun 03, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Revolver (Stereo - 2009 remaster)

Official album • Released in 2009

2:28 • Studio version • B2009 • Stereo • 2009 stereo remaster

- Paul McCartney :

- Backing vocals, Bass, Handclaps, Piano

- Ringo Starr :

- Drums, Handclaps, Maracas

- John Lennon :

- Backing vocals, Handclaps, Tambourine

- George Harrison :

- Handclaps, Lead guitar, Lead vocals

- George Martin :

- Producer

- Geoff Emerick :

- Recording engineer

- Guy Massey :

- Remastering

- Steve Rooke :

- Remastering

- Allan Rouse :

- Project co-ordinator

- Session Recording:

- Jun 02, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Overdubs:

- Jun 03, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Mixing:

- Jun 21, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Official album • Released in 2014

2:28 • Studio version • A2009 • Mono • 2009 remaster

- Paul McCartney :

- Backing vocals, Bass, Handclaps, Piano

- Ringo Starr :

- Drums, Handclaps, Maracas

- John Lennon :

- Backing vocals, Handclaps, Tambourine

- George Harrison :

- Handclaps, Lead guitar, Lead vocals

- George Martin :

- Producer

- Geoff Emerick :

- Recording engineer

- Paul Hicks :

- Remastering

- Guy Massey :

- Remastering

- Sean Magee :

- Remastering

- Allan Rouse :

- Project co-ordinator

- Session Recording:

- Jun 02, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Overdubs:

- Jun 03, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Mixing:

- Jun 03, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Official album • Released in 2014

2:28 • Studio version • B2009 • Stereo • 2009 remaster

- Paul McCartney :

- Backing vocals, Bass, Handclaps, Piano

- Ringo Starr :

- Drums, Handclaps, Maracas

- John Lennon :

- Backing vocals, Handclaps, Tambourine

- George Harrison :

- Handclaps, Lead guitar, Lead vocals

- George Martin :

- Producer

- Geoff Emerick :

- Recording engineer

- Guy Massey :

- Remastering

- Steve Rooke :

- Remastering

- Allan Rouse :

- Project co-ordinator

- Session Recording:

- Jun 02, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Overdubs:

- Jun 03, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Mixing:

- Jun 21, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Revolver (UK Mono - 2014 vinyl)

LP • Released in 2014

2:28 • Studio version • A2014 • Mono • 2014 remaster

- Paul McCartney :

- Backing vocals, Bass, Handclaps, Piano

- Ringo Starr :

- Drums, Handclaps, Maracas

- John Lennon :

- Backing vocals, Handclaps, Tambourine

- George Harrison :

- Handclaps, Lead guitar, Lead vocals

- George Martin :

- Producer

- Geoff Emerick :

- Recording engineer

- Sean Magee :

- Remastering

- Steve Berkowitz :

- Remastering

- Session Recording:

- Jun 02, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Overdubs:

- Jun 03, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

- Session Mixing:

- Jun 03, 1966

- Studio :

- EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Live performances

Paul McCartney has never played this song in concert.

Contribute!

Have you spotted an error on the page? Do you want to suggest new content? Or do you simply want to leave a comment ? Please use the form below!