- Album This interview has been made to promote the Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (UK Mono) LP.

Timeline

More from year 1967

Songs mentioned in this interview

Officially appears on Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (UK Mono)

Officially appears on All You Need Is Love / Baby You're A Rich Man (UK)

Officially appears on Yesterday and Today (Mono)

Officially appears on Revolver (UK Mono)

Officially appears on Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (UK Mono)

Officially appears on Love Me Do / P.S. I Love You

Officially appears on Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (UK Mono)

Officially appears on Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (UK Mono)

Officially appears on Strawberry Fields Forever / Penny Lane

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

Officially appears on Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (UK Mono)

Officially appears on Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (UK Mono)

Officially appears on Revolver (UK Mono)

Interviews from the same media

1969 • From The Observer

Mar 11, 2001 • From The Observer

2003 • From The Observer

When the McCartneys came for lunch

Apr 29, 2007 • From The Observer

Pete Doherty meets Paul McCartney

Oct 14, 2007 • From The Observer

Spread the love! If you like what you are seeing, share it on social networks and let others know about The Paul McCartney Project.

Interview

This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

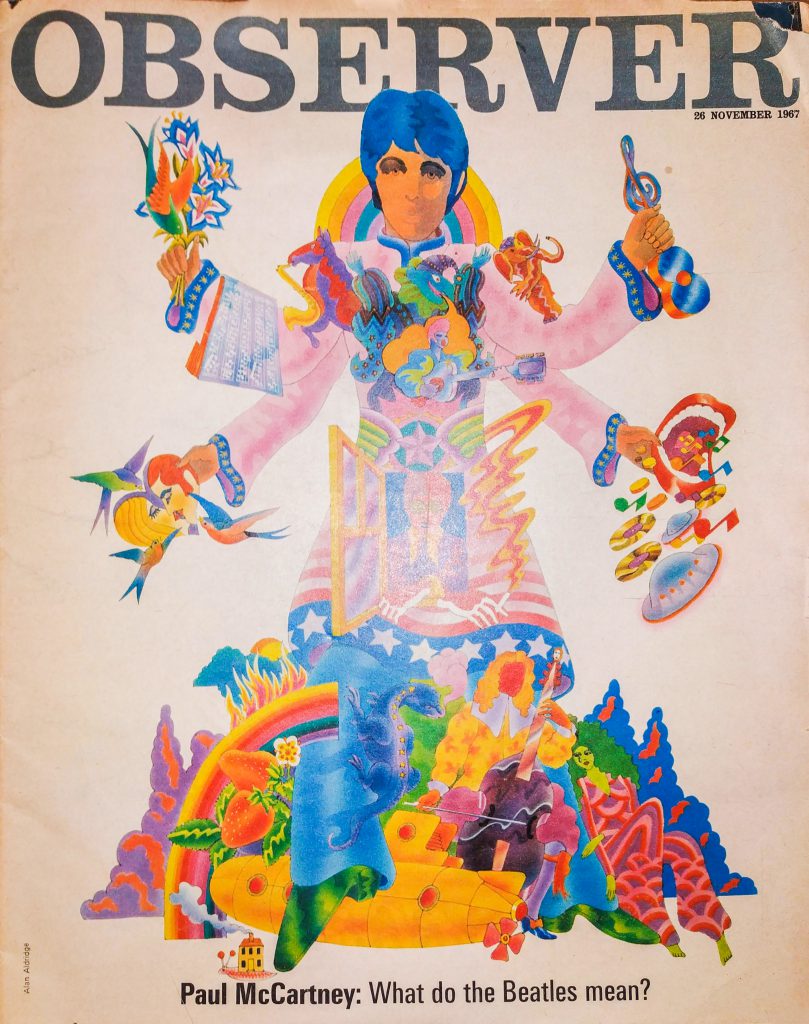

In this interview, Paul McCartney talked to Alan Aldridge, a British artist, graphic designer and illustrator, who is best known for his psychedelic artwork made for books and record covers by The Beatles and The Who. He especially made the illustrations for the two-volume book “The Beatles Illustrated Lyrics“, published in 1969 and 1971.

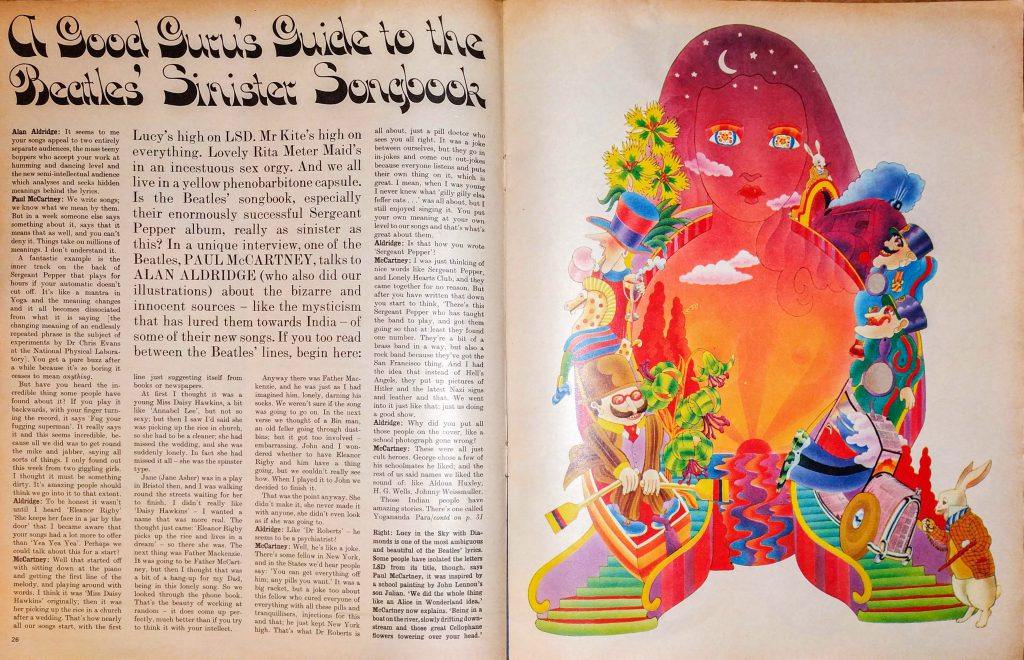

A Good Guru’s Guide to the Beatles’ Sinister Songbook

Lucy’s high on LSD. Mr Kite’s high on everything. Lovely Rita Meter Maid’s in an incestuous sex orgy. And we all live in a yellow phenobarbitone capsule. Is the Beatles’ songbook, especially their enormously successful Sergeant Pepper album, really as sinister as this? In a unique interview, one of the Beatles, PAUL McCARTNEY, talks to ALAN ALDRIDGE (who also did our illustrations) about the bizarre and innocent sources — like the mysticism that has lured them towards India — of some of their new songs. If you too read between the Beatles’ lines, begin here:

Alan Aldridge: It seems to me your songs appeal to two entirely separate audiences, the mass teeny boppers who accept your work at humming and dancing level and the new semi-intellectual audience which analyses and seeks hidden meanings behind the lyrics.

Paul McCartney: We write songs; we know what we mean by them. But in a week someone else says something about it, says that it means that as well, and you can’t deny it. Things take on millions of meanings. I don’t understand it.

A fantastic example is the inner track on the back of Sergeant Pepper that plays for hours if your automatic doesn’t cut off. It’s like a mantra in Yoga and the meaning changes and it all becomes dissociated from what it is saying [the changing meaning of an endlessly repeated phrase is the subject of experiments by Dr Chris Evans at the National Physical Laboratory]. You get a pure buzz after a while because it’s so boring it ceases to mean anything.

But have you heard the incredible thing some people have found about it? If you play it backwards, with your finger turning the record, it says ‘Fug your fugging superman’. It really says it and this seems incredible, because all we did was to get round the mike and jabber, saying all sorts of things. I only found out this week from two giggling girls. I thought it must be something dirty. It’s amazing people should think we go into it to that extent.

Aldridge: To be honest it wasn’t until I heard ‘Eleanor Rigby’ ‘She keeps her face in a jar by the door’ that I became aware that your songs had a lot more to offer than ‘Yea Yea Yea’. Perhaps we could talk about this for a start?

McCartney: Well that started off with sitting down at the piano and getting the first line of the melody, and playing around with words. I think it was ‘Miss Daisy Hawkins’ originally; then it was her picking up the rice in a church after a wedding. That’s how nearly all our songs start, with the first line just suggesting itself from books or newspapers.

At first I thought it was a young Miss Daisy Hawkins, a bit like ‘Annabel Lee’, but not so sexy; but then I saw I’d said she was picking up the rice in church, so she had to be a cleaner; she had missed the wedding, and she was suddenly lonely. In fact she had missed it all — she was the spinster type.

Jane (Jane Asher) was in a play in Bristol then, and I was walking round the streets waiting for her to finish. I didn’t really like ‘Daisy Hawkins’ — I wanted a name that was more real. The thought just came: ‘Eleanor Rigby picks up the rice and lives in a dream’ — so there she was. The next thing was Father Mackenzie. It was going to be Father McCartney, but then I thought that was a bit of a hang-up for my Dad, being in this lonely song. So we looked through the phone book. That’s the beauty of working at random — it does come up perfectly, much better than if you try to think it with your intellect.

Anyway, there was Father Mackenzie, and he was just as I had imagined him, lonely, darning his socks. We weren’t sure if the song was going to go on. In the next verse we thought of a Bin man, an old feller going through dustbins; but it got too involved — embarrassing. John and I wondered whether to have Eleanor Rigby and him have a thing going, but we couldn’t really see how. When I played it to John we decided to finish it.

That was the point anyway. She didn’t make it, she never made it with anyone, she didn’t even look as if she was going to.

Aldridge: Like ‘Doctor Robert’ — he seems to be a psychiatrist?

McCartney: Well, he’s like a joke. There’s some fellow in New York, and in the States we’d hear people say: ‘You can get everything off him; any pills you want.’ It was a big racket, but a joke too about this fellow who cured everyone of everything with all these pills and tranquillisers, injections for this and that; he just kept New York high. That’s what Dr. Roberts is all about, just a pill doctor who sees you all right. It was a joke between ourselves, but they go in in-jokes and come out out-jokes because everyone listens and puts their own thing on it, which is great. I mean, when I was young I never knew what ‘gilly gilly elsa feffer cats . . .’ was all about, but I still enjoyed singing it. You put your own meaning at your own level to our songs and that’s what’s great about them.

Aldridge: Is that how you wrote ‘Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’?

McCartney: I was just thinking of nice words like Sergeant Pepper, and Lonely Hearts Club, and they came together for no reason. But after you have written that down you start to think, ‘There’s this Sergeant Pepper who has taught the band to play, and got them going so that at least they found one number. They’re a bit of a brass band in a way, but also a rock band because they’ve got the San Francisco thing. And I had the idea that instead of Hell’s Angels, they put up pictures of Hitler and the latest Nazi signs and leather and that. We went into it just like that: just us doing a good show.

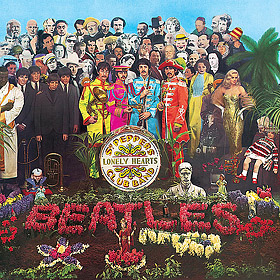

Aldridge: Why did you put all those people on the cover, like a school photograph gone wrong?

McCartney: These were all just cult heroes. George chose a few of his schoolmates he liked; and the rest of us said names we liked the sound of: like Aldous Huxley, H. G. Wells, Johnny Weissmuller.

Those Indian people have amazing stories. There’s one called Yogananda Para Manza, who died in 1953 and left his body in an incredibly perfect state. Medical reports in Los Angeles three or four months after he died were saying this is incredible; this man hasn’t decomposed yet. He was sitting there glowing because he did this sort of transcendental bit, transcended his body by planes of consciousness. He was taught by another person on the cover and he was taught by another, and it all goes back to the one called Babujee who’s just a little drawing looking upwards.

You can’t photograph him – he’s an agent. He puts a curse on the film. He’s the all-time governor, he’s been at it a long time and he’s still around doing the transcending bit.

Aldridge: These are all George’s heroes?

McCartney: Yes. George says the great thing about people like Babujee and Christ and all the governors who have transcended is that they’ve got out of the reincarnation cycle: they’ve reached the bit where they are just there; they don’t have to zoom back.

So they’re there planning the spiritual thing for us. So, if they are planning it, what a groove that he’s got himself on our cover, night in the middle of the Beatles’ LP cover! Normal ideas of God wouldn’t have him interested in Beatles music or any pop – it’s a bit infra dig – but obviously, if we’re all here doing it, and someone’s interested in us, then it’s all to do with it. There’s not one bit worse than another bit. So that’s great, that’s beautiful that he’s right on the cover with all his mates.

Whatever it is, it’s what is doing all those trees and doing us and keeping you going; which someone must be doing.

The Yogi goes through millions of things to realise the simplest of all truths, because while you are going through this part, there’s always the opposite truth. You say, ‘Ah well, that’s all there is to it then. It’s all great, and God’s looking after you.’ Then Someone says, ‘What about a hunchback then, is that great?” And you say, ‘OK then, it’s all lousy.’ And this is just as true if you want to see it. But the truth is that it’s neither good nor lousy; Just down the middle; a state of being that doesn’t have black or white, good or bad.

Aldridge: Is that what George’s number is about?

McCartney: I think George’s awareness has helped us because he got into this through Indian music – or as he calls it, ‘All India Radio’. There’s such a sense of vision in Indian music that it’s just like meditation. You can play it forever; there’s just no end to what you can play on a sitar and how good you can get.

Aldridge: It struck me that Sergeant Pepper is one of the first LPs that has looked at the idiom either like a symphony or a paperback: trying to present a complete show that lasts an hour.

McCartney: That’s it. We realised for the first time that someday someone would actually be holding a thing that they’d call ‘The Beatles’ new LP’ and that normally it would just be a collection of songs or a nice picture on the cover, nothing more. So the idea was to do a complete thing that you could make what you liked of; just a little magic presentation. We were going to have a little envelope in the centre with the nutty things you can buy at Woolworth’s: a surprise packet.

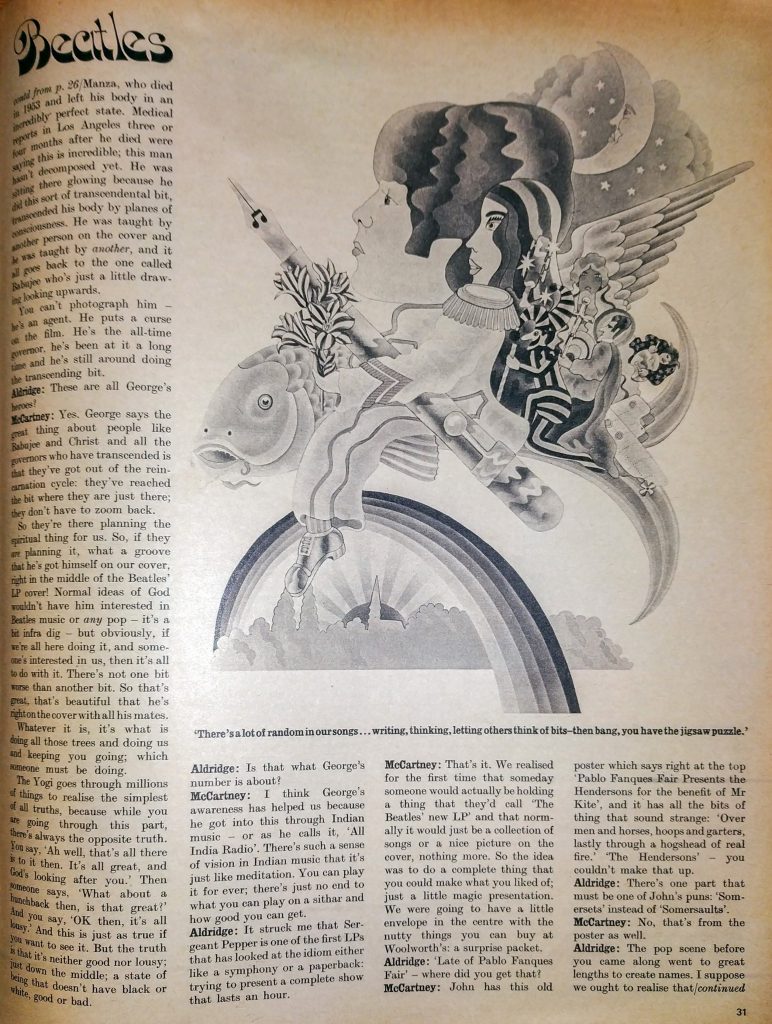

Aldridge: ‘Late of Pablo Fanques Fair’ – where did you get that?

McCartney: John has this old poster which says right at the top ‘Pablo Fanques Fair Presents the Hendersons for the benefit of Mr. Kite’, and it has all the bits of thing that sound strange: ‘Over men and horses, hoops and garters, lastly through a hogshead of real fire.’ ‘The Hendersons’ – you couldn’t make that up.

Aldridge: There’s one part that must be one of John’s puns: ‘Somersets’ instead of ‘Somersaults’.

McCartney: No, that’s from the poster as well.

Aldridge: The pop scene before you came along went to great lengths to create names. I suppose we ought to realise that you can’t do better than real fact — your own actual experience of life.

McCartney: There’s no need to make things up. We started on interviewers who would say, ‘What do you believe!’ and we’d say, ‘We do not believe in gold lamé suits: that’s trying to glory it up and doesn’t even do it well.’ That detaches you from the real thing. That’s why Daisy Hawkins wasn’t any good — it sounds like Daisy made-up. Billy Shears is another that sounds like a schoolmate but isn’t. Possibly one day we’ll meet all these people.

Aldridge: One of the most obviously ambiguous of your songs, the one that everybody can see something in, is ‘Lucy in the Sky Diamonds’.

McCartney: This one is amazing. As I was saying before, when you write a song and you mean it one way, and then someone comes up and says something about it that you didn’t think of — you can’t deny it. Like ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’, people came up and said, very cunningly, ‘Right, I get it. L — S — D’ and it was when all the papers were talking about LSD, but we never thought about it.

Aldridge: If you take LSD as a sort of pun, the whole song is a trip.

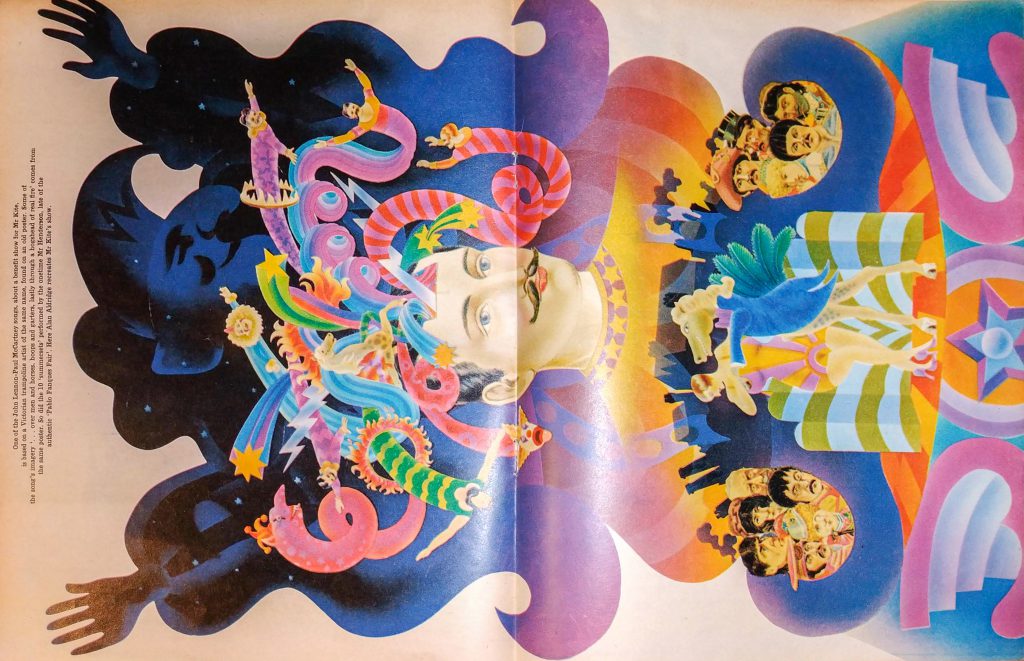

McCartney: What happened was that John’s son Julian did a drawing at school and brought it home, and he has a schoolmate called Lucy, and John said what’s that, and he said ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’ — so we had a nice title. We did the whole thing like an Alice in Wonderland idea, being in a boat on the river, slowly drifting downstream and those great Cellophane flowers towering over your head. Every so often it broke off and you saw Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds all over the sky. This Lucy was God, the big figure, the white rabbit. You can just write a song with imagination on words and that’s what we did.

It’s like modern poetry, but neither John nor I have read much. The last time I approached it I was thinking ‘This is strange and far out’, and I did not dig it all that much, except Dylan Thomas who I suddenly started getting, and I was quite pleased with myself because I got it, but I hadn’t realised he was going to be saying exactly the same things.

It’s just that we’ve at last stopped trying to be clever, and we just write what we like to write. If it comes out clever, OK. You get to the bit where you think, if we’re going to write great philosophy it isn’t worth it. ‘Love Me Do’ was our greatest philosophical song: ‘Love me do/ you know I love you/l’ll always be true/So love me do/Please love me, do.’ For it to be simple, and true, means that it’s incredibly simple.

Aldridge: People have told me that ‘Fixing a Hole’ is all about junk, you know, this guy, sitting there fixing a hole in his arm.

McCartney: This song is just about the hole in the road where the rain gets in; a good old analogy — the hole in your make-up which lets the rain in and stops your mind from going where it will. It’s you interfering with things; as when someone walks up to you and says, ‘I am the Son of God.’ And you say, ‘No you’re not; I’ll crucify you,’ and you crucify him. Well that’s life, but it is not fixing a hole.

It’s about fans too: ‘See the people standing there/who disagree and never win/and wonder why they don’t get in/Silly people, run around/they worry me/and never ask why they don’t get in my door.’ If they only knew that the best way to get in is not to do that, because obviously anyone who is going to be straight and like a real friend and a real person to us is going to get in; but they simply stand there and give off, ‘We are fans, don’t let us in.’

Sometimes I invite them in, but it starts to be not really the point in a way, because I invited one in, and the next day she was in the Daily Mirror with her mother saying we were going to get married. So we tell the fans, ‘Forget it.’

If you’re a junky sitting in a room fixing a hole then that’s what it will mean to you, but when I wrote it I meant if there’s a crack or the room is uncolourful, then I’ll paint it.

Aldridge: ‘She’s leaving Home’ is a great song, very simple, similar to ‘Eleanor Rigby’.

McCartney: It’s a much younger girl, but the same sort of loneliness. That was a Daily Mirror story again: This girl left home and her father said: ‘We gave her everything, I don’t know why she left home.’ But he didn’t give her that much, not what she wanted when she left home.

Aldridge: Fine. What’s ‘Lovely Rita’ all about?

McCartney: I was bopping about on the piano in Liverpool when someone told me that in America they call parking-meter women meter maids. I thought that was great, and it got to Rita Meter Maid and then Lovely Rita Meter Maid and I was thinking vaguely that it should be a hate song: ‘You took my car away and I’m so blue today.’ And you wouldn’t be liking her; but then I thought it would be better to love her and if she was very freaky too, like a military man, with a bag on her shoulder. A foot stomper, but nice.

The song was imagining if somebody was there taking my number and I suddenly fell for her, and the kind of person I’d be, to fall for a meter maid, would be a shy office clerk and I’d say, ‘May I inquire discreetly when you are free to take some tea with me.’ Tea, not pot. It’s like saying, ‘Come and cut the grass’ and then realising that could be pot, or the old teapot could be something about pot. But I don’t mind pot and I leave the words in. They’re not consciously introduced just to say pot and be clever.

Aldridge: After a ‘little like a military man’ there’s a fantastic ‘Whoop Whoop’. How did you do that?

McCartney: It’s done with a comb and paper. We had it in the bit after and it sounded too corny; it wasn’t quite good enough to have twice, but in a way that’s nice because you listen for it to come round again.

There’s a lot of random in our songs — Strawberry Fields is the name of a Salvation Army School — by the time we’ve taken it through the writing stage, thinking of it, playing it to the others, writing it, and letting them think of bits, recording it once and deciding it’s not quite right and do it again and then find ‘Oh, that’s it, the solo comes here and that goes there’, then bang, you have the jigsaw puzzle.

That happens with all our songs, except the ones we want to keep really simple, like ‘When I’m 64’ and ‘Fixing a Hole’.

Aldridge: What kind of scene are you thinking of when you say ‘Took her home and nearly made it, sitting on the sofa with a sister or two’?

McCartney: That’s it: there are a couple of sisters around so that is why I never made it.

Aldridge: I could see a whole scene of naked bodies writhing on the sofa . . .

McCartney: If it had been really made…

Aldridge: Then the tricky one that the BBC banned – ‘A Day in the Life’. It’s been said that this is a sort of requiem to Tara Brown (the heir to the Guinness Trust, killed last December in a car crash in London).

McCartney: I’ve heard that. I don’t think John had that in mind at all. The real words to that are ‘Read the news today’. There’d been a story about a man who’d made the grade, and there’d been a photograph of him sitting in his car. John said ‘I had to laugh’. He’d sort of blown his mind out in the car.

Aldridge: Literally, with a gun?

McCartney: No, he was just high on whatever he uses, say he was pissed in this big Bentley, sitting at the traffic lights. He’s driving today; the chauffeur isn’t there, and maybe he got high because of that. The lights have changed and he hasn’t noticed that there’s a crowd of housewives and they’re all looking at him saying ‘Who’s that? I’ve seen him in the papers’ and they’re not sure if he’s from the House of Lords. He looks a bit like that with his homburg and white scarf and he’s out of his screws.

That’s a bit of black comedy. The next bit was another song altogether but it just happened to fit. It was just me remembering what it was like to run up the road to catch a bus to school, having a smoke and going into class. We decided: ‘Bugger this, we’re going to write a turn-on song.’ It was a reflection of my school days — I would have a Woodbine then, and somebody would speak and I would go into a dream.

This was the only one in the album written as a deliberate provocation. A stick-that-in-your-pipe… But what we want is to turn you on to the truth rather than pot.

Aldridge: ‘Yellow Submarine’ has connotations — I read that in Greenwich Village they call yellow phenobarbitone capsules — nembutals — ‘yellow submarines’.

McCartney: I knew it would get connotations, but it really was a children’s song. I just loved the idea of kids singing it. With ‘ Yellow Submarine’ the whole idea was ‘If someday I came across some kids singing it, that will be it’, so it’s got to be very easy — there isn’t a single big word. Kids will understand it easier than adults. ‘In the Town where I was born/there lived a man who sailed to sea/And he told of his life in the land of submarines.’

That’s really the beginning of a kids’ story. There’s some stuff in Greece like icing sugar — you eat it. It’s like a sweet and you drop it into water. It’s called submarine; we had it on holiday.

Aldridge: But some of your songs are real places and real facts. Can you remember the little influences that made ‘Penny Lane’, for example?

McCartney: Penny Lane is a bus roundabout in Liverpool; and there is a barber’s shop showing photographs of every head he’s had the pleasure to know — no that’s not true, they’re just photos of hairstyles, but all the people who come and go/stop and say hullo. There’s a bank on the corner so we made up the bit about the banker in his motor car. It’s part fact, part nostalgia for a place which is a great place, blue suburban skies as we remember it, and it’s still there.

And we put in a joke or two: ‘fish and finger pie.’ The women would never dare say that, except to themselves. Most people wouldn’t hear it, but ‘finger pie’ is just a nice little joke for the Liverpool lads who like a bit of smut.

Aldridge: I’ve heard it said that George Martin writes most of your music.

McCartney: He always has something to do with it, but sometimes more than others. For instance, he wrote the end of ‘All You Need is Love’ and got into trouble because the ‘In the Mood’ bit was copyrighted. We thought of all the great clichés because they’re a great bit of random. It was a hurried session and didn’t mind giving him that to do — saying ‘There’s the end, we want it to go on and on’. Actually what he wrote was much more disjointed, so when we put all the bits together we said, ‘Could we have Greensleeves right on top of that little Bach thing?’ And on top of that, we had the ‘In the Mood’ bit.

George is quite a sage. Sometimes he works with us, sometimes against us; he’s always looked after us. I don’t think he does as much as some people think. He sometimes does all the arrangements and we just change them.

Aldridge: Finally, many people in the trade tell me Ringo can’t drum.

McCartney: That’s extraordinary. He wasn’t on our first record; with ‘Love me Do’ Ringo was on the LP and Andy White on the single and you really notice the difference. What a long time ago that was.

Last updated on September 1, 2023

Contribute!

Have you spotted an error on the page? Do you want to suggest new content? Or do you simply want to leave a comment ? Please use the form below!