- Album This interview has been made to promote the Kisses On the Bottom Official album.

Timeline

More from year 2012

Interviews from the same media

Sep 18, 1966 • From The Sunday Times

Jan 22, 1967 • From The Sunday Times

Apr 06, 2008 • From The Sunday Times

A Lucky Man Who Made The Grade

Feb 05, 2012 • From The Sunday Times

Paul McCartney interview: the Beatles star on seeing God, teaching Stormzy to play piano..

Sep 02, 2018 • From The Sunday Times

Paul McCartney on what climate change and Brexit mean for his grandchildren

Aug 30, 2019 • From The Sunday Times

Sunny Side Up - Paul McCartney On The Joy Of Making His New Solo Album

Dec 05, 2020 • From The Sunday Times

Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr: We never thought the Beatles would last

Nov 04, 2023 • From The Sunday Times

Spread the love! If you like what you are seeing, share it on social networks and let others know about The Paul McCartney Project.

Interview

The interview below has been reproduced from this page . This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

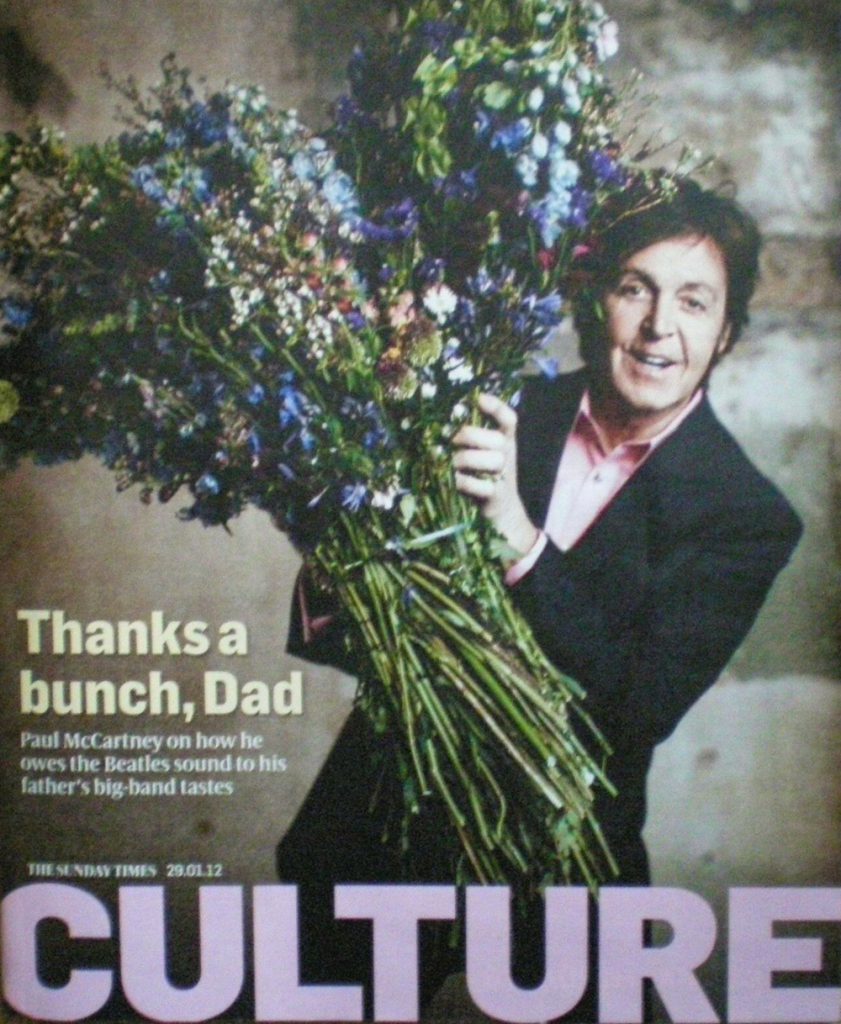

When Paul McCartney made the decision to name his new album Kisses on the Bottom, his choice was met with not only raised eyebrows, but, in some quarters, panic. McCartney’s motive was in part, he admits, to make mischief. “I like mischief,” the former Beatle says. “It’s good for the soul, it’s always a good idea — if only because people think it’s a bad idea.”

The album sees McCartney backed by Diana Krall and her band on a set of interwar and post-war standards — classics by the likes of Harold Arlen, Frank Loesser and Irving Berlin, including It’s Only a Paper Moon, The Glory of Love, More I Cannot Wish You and Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate the Positive. They are of the type he grew up hearing his band-leader father, Jim, play, and certainly a departure for the newly remarried 69-year-old. McCartney Sr would surely have approved — not to mention known in an instant where that provocative title came from. Lifting a line from Fats Waller’s 1935 hit I’m Going to Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter, which opens the new album, it serves as a fitting tribute to the man Macca credits with giving him his introduction to music and melody.

“My first musical memories come from my dad,” McCartney says. “He would play the piano at home — he and his friend Freddie Rimmer, both of whom worked at the cotton exchange in Liverpool, as salesmen. This was the old days, you know, ‘We make our own entertainment’, because you didn’t have anything else. And those old memories, for me, are of my dad playing the piano. I would lie on the carpet, listening to him and taking it all in. I think a lot of my musicality came from then. I was hearing quite complex songs, which the songs of that era were. He used to do a little thing called Stumbling” — as McCartney, spine-tinglingly, launches into the old Zez Confrey number, you hear immediately an irrefutable link with his White Album song Honey Pie — “and the syncopation there is kind of interesting, it’s not four-square.”

Curiosity has always characterised McCartney’s work — sometimes to its detriment, as when his restless musical brain has followed trails a cooler, harder head might have left unblazed. (His recent, poorly received ballet, Ocean’s Kingdom, is an example of this.) More often, though, it is this aspect of his creativity that has helped to explain both the endless innovations he and the other Beatles were responsible for and the nomadic nature of his subsequent artistic output. The era the record pays homage to is one McCartney has visited before — on Fab Four songs such as When I’m Sixty-Four (which he wrote when the Beatles were in their infancy), Martha My Dear and the aforementioned Honey Pie, and on later Wings tracks such as You Gave Me the Answer. On Only Our Hearts, one of two McCartney originals on the album, and a song featuring a mouth-watering harmonica solo from Stevie Wonder (Eric Clapton plays on the other), you can again trace a direct line, in this case from The Long and Winding Road, through the early Wings song My Love, to the new composition.

Following the chain and locating new links continues to absorb McCartney, just as it did when I last met him, five years ago. On the morning of our meeting a fortnight ago at the Soho HQ of his multimillion-pound publishing and recording empire, I had just opened a text from his publicist, and was reading it as I almost bumped into a fast-moving man coming towards me on the pavement. It was, of course, McCartney. I didn’t stop him. He is known to walk around London a lot, but can do so only if he stays on the move. Make him cool his heels and, within seconds, he will be surrounded. That is the level of his fame.

It helps to bear this in mind when you assess the work he has produced, and the sanity he has clung to, since the Beatles split up. It is probably safe to assume that he isn’t expecting his new album to start many fires or shoot out the lights — let alone convert his detractors. Yet the record will fascinate his fans, not least for the dots it joins (those old links again) — dots that were also joined during his extraordinary, incandescent three-hour set at the O2 Arena, in London, last month. And, as is evident when he talks about both devising and recording it, the album also fascinated McCartney — for the lessons it taught him and the memories it triggered.

“I realise now that a lot of what informed the writing I did with John was that early period, and John and I shared that. You would think that, maybe because of my father, that was my specific thing — because John’s dad ran away to sea, when he was three, I think. But when we started to talk about it, John would say, ‘Oh, I love such-and-such song.’ His two favourites that I remember were Little White Lies and Close Your Eyes [McCartney starts to sing again: ‘Close your eyes, / Rest your head on my shoulder and sleep’]. And that was an attraction for me, with John, because I realised that it wasn’t that we liked rock’n’roll solely. And I think that when you look now at the Beatles’ body of work, it was sort of rock’n’roll informed by this back plot from this complete other era.

“When people ask me why I think the Beatles’ stuff has lasted, I’ve had to try to figure out my answer to that, and over the years I’ve realised. I now answer, ‘Structure.’ They’re well structured, those songs — there is nothing that doesn’t need to be there. That sounds a bit immodest, but it’s a body of work now, so I can talk like that.”

And structure, along with unpredictability and, musically, a willingness to roam, was, of course, a characteristic of the era the new album covers. “Dick Lester,” McCartney continues, referring to the man who directed the first two Beatles feature films, “always used to say that what he liked in our songs was that he always thought he could tell where they were going to go, and they didn’t. We hadn’t realised that. I suppose that, for it to work, and for us to turn out to be any good at all, that had to be something we naturally had, that sense of ‘We don’t want it to go to the obvious place, let’s go here’. And I think that some of those clues, if you like, were in that earlier music.”

Most of the album was recorded at the famous Capitol Studios, in Hollywood, and, for the first time, McCartney’s only role was as a vocalist — an experience he admits he found problematic at first. “Here was I in this completely new role, feeling really quite intimidated. There was nothing to hide behind, no guitar or piano that I could put between me and ‘it’. I had to sort of find a vocal style, and I started off full-voice. A lot of the songs are rangy, they go from low notes to high notes. And I was going [he puts on his rock voice] ‘Wah wah-eeh’, and thinking, ‘Oh my God, I didn’t realise this song had such a high note [in it].’ I’m in front of really good musicians, who know what’s going on, and I’m thinking, ‘Bloody hell, I’m going to totally disgrace myself here. I’m going to be, like, the worst person in this band, and I’m supposed to be, like, not bad. They’re all going to be smiling at me, but secretly thinking, Jesus Christ, this guy is rubbish.’ Then I think, ‘Get it together, Macca, come on.’

“The engineer goes, ‘You know you’re on Nat King Cole’s mike?’ So I decide that I’m going to get in on the mike. And I was joking with Diana afterwards — ‘I don’t know what’s happened, I’ve turned into Whispering Jack Smith.’ So, yeah, me not having an instrument was very strange, very intimidating. It took me a few songs to settle into it — and,” he chuckles, “needless to say, they’re not on the album.”

The recording sessions, which were produced by Tommy LiPuma (Miles Davis, Al Jarreau et al) were, McCartney says, all about working “organically”. “The nicest thing about that, and I realised this after we’d done it, was that it was the way the Beatles would work — bring in an idea, which you hadn’t rehearsed, with nobody knowing how the end product was going to turn out. For instance, we’d go in with, I don’t know, Eight Days a Week, and go, ‘Here it is’, and we’d sketch it out, show each other how it went, then it would be, ‘Well, what about an intro. And you’d go, ‘Da-da-da-da, sounds good, okay.’ And over the next half an hour” — half an hour! — “we’d format it, then we’d go and record it.”

We return to the question of the album title. He obviously knew, I suggest, the trouble it would cause. “The more I looked at it,” McCartney answers, with a twinkle in his eye, “the more serious about it I became, and I thought, ‘Do you know what, that’s going to put the cat among the pigeons.’ So I made the suggestion and got this nervous text [from the label] — ‘Paul, under no circumstances can we do this.’ One of the guys said he felt like he’d been punched in the gut. And I said, ‘Listen to me, the very first time I had this reaction was when we told people the name of our group.’” And what was the reaction on that occasion? “People freaked,” McCartney laughs. “You know, ‘Creepy-crawly insects?’”

Contribute!

Have you spotted an error on the page? Do you want to suggest new content? Or do you simply want to leave a comment ? Please use the form below!