Part of

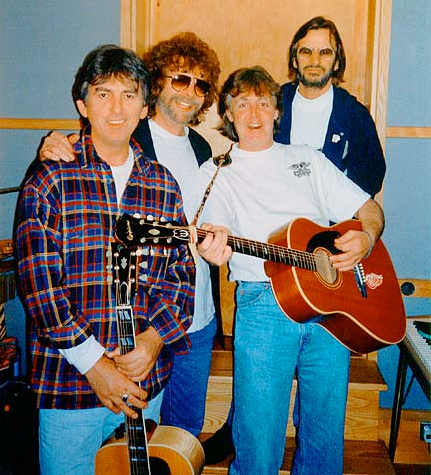

"The Beatles Anthology" sessions

Feb 11, 1994 - 1996 • Songs recorded during this session appear on Anthology 1

- Album Songs recorded during this session officially appear on the Anthology 1 Official album.

- Studio:

- Hog Hill Studio, Rye, UK

Timeline

More from year 1994

Some songs from this session appear on:

Spread the love! If you like what you are seeing, share it on social networks and let others know about The Paul McCartney Project.

About

(the content of this page was taken from https://reunionsessions.tripod.com/al/faabsessions/1994a.html , with changes introduced)

In January 1994, when Paul came over to New York to induct John into the Rock Hall Of Fame, Yoko apparently gave Paul tapes of at least four John Lennon compositions (the exchange definitely involved more than three songs). Neil Aspinall claims he believes the transaction consisted of “two cassettes” of John’s songs, “It might have been five or six tracks.” It’s possible at this stage that the fourth Lennon demo, entitled “Now And Then”, which had not been heard publically before, was handed over by Yoko.

Yoko: It was all settled before then, I just used that occasion to hand over the tapes personally to Paul. I did not break up the Beatles, but I was there at the time, you know? Now I’m in a position where I could bring them back together and I would not want to hinder that. It was kind of a situation given to me by fate.

Paul: So I took the tapes back, got copies made for the guys and they liked it.

Ringo: And that’s how it came about. It was just a natural thing which gradually evolved. It actually took about three years for all this to happen.

Paul: I played these songs to the other guys, warning Ringo to have his hanky ready. I fell in love with “Free As A Bird“. I thought I would have loved to work with John on that. I liked the melody, it’s got strong chords and it really appealed to me. Ringo was very up for it, George was very up for it, I was very up for it. I actually originally heard it as a big, orchestral, forties Gershwin thing, but it didn’t turn out like that. Often your first vibe isn’t always the one. You go through a few ideas and someone goes ‘bloody hell’ and it gets knocked out fairly quickly. In the end, we decided to do it very simply.

The first recording sessions with Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr since the break-up of the Beatles in July then started on February 11th, 1994. The work on “Free As A Bird” was quite fruitful – they completed the work on this track during those February sessions which lasted till the end of the month. But time and effort were also spent on the three other songs.

From Wikipedia about the work on “Free As A Bird“:

[…] George Martin, who had produced most of the Beatles’ 1960s recordings, turned down an invitation to produce “Free as a Bird” due to hearing problems (though he subsequently managed to produce and direct the Anthology series). Harrison, in turn, suggested Lynne as producer, and work commenced at McCartney’s studio in February 1994. Geoff Emerick and Jon Jacobs were chosen to engineer the new tracks.

The original tape of Lennon singing the song was recorded on a mono cassette, with vocals and piano on the same track. They were impossible to separate, so Lynne had to produce the track with voice and piano together, but commented that it was good for the integrity of the project, as Lennon was not only singing occasional lines, but also playing on the song.

Although Lennon had died in 1980, Starr said that the three remaining Beatles agreed they would pretend that Lennon had “gone for lunch“, or had gone for a “cup of tea“. The remaining Beatles recorded a track around Lennon’s basic song idea, but which had gaps they had to fill in musically. Some chords were changed, and the arrangement was expanded to include breaks for McCartney and Harrison to sing extra lines. Harrison played slide guitar in the solo.

The Beatles’ overdubs and production were recorded between February and March 1994 in Sussex, England, at McCartney’s home studio. It ends with a slight coda including a strummed ukulele by Harrison (an instrument he was known to have played often) and the voice of John Lennon played backwards. The message, when played in reverse, is “Turned out nice again“, which was the catchphrase of George Formby. The final result sounds like “made by John Lennon“, which, according to McCartney, was unintentional and was only discovered after the surviving Beatles reviewed the final mix. When Starr heard McCartney and Harrison singing the harmonies, and later the finished song, he said that it sounded just like them [The Beatles]. He explained his comment by saying that he looked at the project as “an outsider“. Lynne fully expected the finished track to sound like The Beatles, as that was his premise for the project, but Harrison added: “It’s gonna sound like them [The Beatles] if it is them… It sounds like them now” [in the present].

McCartney, Harrison and Starr all agreed that the recording process was more pleasurable than when they later recorded “Real Love” (the second song chosen for release); as it was almost finished, they had very little input, and felt like sidemen for Lennon. […]

Worth noting that George Martin, also declared about “Free As A Bird“:

When Paul, George and Ringo recorded the two new Beatles songs, Free As A Bird and Real Love, did they ask you to be involved?

I kind of told them I wasn’t too happy with putting them together with the dead John. I’ve got nothing wrong with dead John but the idea of having dead John with live Paul and Ringo and George to form a group, it didn’t appeal to me too much. In the same way that I think it’s okay to find an old record of Nat King Cole’s and bring it back to life and issue it, but to have him singing with his daughter is another thing. So I don’t know, I’m not fussy about it but it didn’t appeal to me very much. I think I might have done it if they asked me, but they didn’t.

Did you enjoy Jeff Lynne’s production of Free As A Bird and Real Love?

I thought what they did was terrific; it was very very good indeed. I don’t think I would have done it like that if I had produced it.

What would you have done differently?

Well, you see the way they did it you must remember the material they had to deal with was very difficult. It was a cassette that John had placed on top of his piano, played and sang. The piano was louder than the voice, and the voice wasn’t very clear and the rhythm was all over the place. So they tried to separate the voice and the piano, not very successfully.

Then they tried to put it into a rigid time beat so they could overdub easily other instruments. So they stretched it and compressed it until it got to a regular waltz and then they were done. The result was, in order to conceal the bad bits, they had to plaster it fairly heavily, so what you ended up with was quite a thick homogeneous sound that hardly stops. There’s not much dynamic in it.

The way I would have tackled it if I had the opportunity would have been the reverse of that. I would have looked at the song as a song and got The Beatles together and say ‘what can we do with this song?’ bearing in mind we have got John around as well somewhere. I would have actually have started to record a song and I would have dropped John into it.

I wouldn’t have made John the basis of it. So where possible I would have used instruments probably and we would then try and get his voice more separate and use him for the occasional voice so it would become a true partnership of voices. Whether that would be practical or not I don’t know, this is just theoretically the way I would tackle it.

George Martin, interviewed by Rock Cellar Magazine, April 2013

About the 1997 Free As A Bird demo

The Free As A Bird late 1977 demo took off from a basic doo-wop chord sequence, taking in some of the stately changes of Grow Old With Me as it progressed. Agonisingly slow, it was written at the piano around a maudlin set of chord changes that virtually guaranteed an air of sadness. The lyrics, certainly incomplete, explored different ways of conveying the metaphor of the title, quite clearly it was the concept rather than any particular lyrical phrase which had been the initial inspiration. Lennon filled the second half of his demo with wordless vocal lines and repetitions of the title phrase, picked up by the tiny mike of a portable tape player placed on top of his piano.

John recorded at least two, possibly three, piano backed demos of Free As A Bird (and in 1998 there were reports than an acoustic guitar demo of the song had also been discovered). This was a tune of great promise that seems to have been written at the piano one day, preserved on tape and forgotten by John. But despite its incomplete lyrics, it had an air of majesty that deserved further attention. What stayed in the mind was the mood, an air of phoenix-like hope drifting uncertainly out of a fog of depression – and that haunting melody.

About the mindset of the three ex-Beatles

Paul: It’s crazy really because when you think about a new Beatles record, it is impossible because John is not around. I invented a little scenario; he’s gone away on holiday and he’s just rung us up and he says “Just finish this track for us, will you? I’m sending the cassette – I trust you.” That was the key thing, “I trust you, just do your stuff on it.” I told this to the other guys and Ringo was particularly pleased, and he said: “Ahh, that’s great!” It was very nice and it was very irreverent towards John. The scenario allowed us to be not too, ahh, the great sacred fallen hero. He would never have gone for that. John would have been the first one to debunk that – “A fucking hero? A fallen hero? Fuck off we’re making a record.”

Ringo: At the beginning it was very hard, knowing that we were going in there to do this track with him. It was pretty emotional. He wasn’t there. I loved John. We had to imagine he’d just gone for a cup of tea, that he’s gone on holiday but he’s still here. That’s the only way I could get through it.

Paul: Once we agreed to take that attitude it gave us a lot of freedom because it meant that we didn’t have any sacred view of John as a martyr, it was John the Beatle, John the crazy guy we remember. So we could laugh and say, ‘Wouldn’t you just know it? It’s completely out of time! He’s always bloody out of time, that Lennon!’ He would have made those jokes if it had been my cassette.

George: Because it was only a demo he was just plodding along and in some places, he’d quicken up and in some places, he’d slow down.

I said to Ringo, ‘Let’s pretend that we’ve nearly finished some recordings and John is going off to Spain on holiday. He’s just rung up and said, ‘There’s one more song I wouldn’t mind getting on the album, but it’s not finished. So if you’re up for it, take it in the studio, do your stuff like you would normally do, have fun with it, and I trust you’. With that scenario in place, Ringo then said, ‘Oh, this could even be joyous’.

And it was. We’d not met for a long time, we did it down in my studio, and the press didn’t guess that we’d be down there. We had technical problems to overcome. But because we said, ‘John’s only left us this tape,’ we could take the piss. That was our attitude, we were never reverent to each other.

Paul McCartney

About the producer

Production duties for the sessions were shared not by George Martin, but by George Harrison’s fellow Traveling Wilbury, Jeff Lynne.

George Martin: The Beatles are very good record producers and they don’t need me anymore. They wanted to keep this project to themselves as much as possible. I knew about it, I knew it was happening and there was no rancour about it. What they did with John’s tape is exceptionally clever and very good. Jeff Lynne has done a brilliant job and having heard it now, I wish I had produced it. I’ve been working on Anthology all year, and if I had to choose between working on the single or the album, I’d have chosen Anthology, because it’s the bigger one.

Paul: George (Martin) wasn’t involved, no. I was originally keen to have George do it. I thought it might be a bit insulting not to ask him to do this. But George doesn’t want to produce much anymore because his hearing’s not as good as it used to be. He’s a very sensible guy and he says, ‘Look, Paul, I like to do a proper job,’ and if he doesn’t feel he’s up to it he won’t do it. It’s very noble of him, actually, most people would take the money and run. Plus George Harrison was keen to make sure we had someone really current with ears. He knew Jeff Lynne. I was worried there might be a bit of a wedge but in fact, it wasn’t like that, it was great. Jeff worked out really well. As I said to him, a lot of people are very wary of your sound. I said you’ve got a sound. He said, “Oh have I?” He’s got a way of working but it’s very similar to some of the ways we worked in the Beatles.

Ringo: We started off with a cassette that Yoko gave us, but the cassette wasn’t in the greatest condition.

Paul: We took a cassette of John’s, it was him and piano, interlocked. You couldn’t pull the fader down and get rid of the piano.

About the pre-production work

Jeff Lynne contacted Marc Mann, an LA studio musician, to assist him in cleaning up the tapes. Mann recalls that the cassettes used were very old and very noisy (others involved, however, claim that Yoko handed over copies of the original cassettes, not the originals themselves).

Lynne: It was very difficult and one of the hardest jobs I’ve ever had to do because of the nature of the source material. It was very primitive sounding, to say the least. Free As A Bird however, wasn’t as quarter as noisy as Real Love, and only a bit of EQ was needed to cure most problems. I spent about a week at my own studio cleaning up both tracks on my computer. So it took a lot of work to get it all in time so that the others could play to it.

Using DINR (Digidesign), Logic Audio (Emagic) and Studio Vision (Opcode) running on a Macintosh computer loaded with ProTools (Digidesign), Marc Mann edited and otherwise massaged the tapes. The pre-production work done by Lynne and Mann was pretty heavy duty, and a dummy of the anticipated final recording was done to see if the concept would actually work before Paul, George or Ringo played a note.

The cassette was dumped to a hard drive and all the processing necessary to clean up the audio was done first (among other things, there was apparently massive tape hiss). The dummy temp tracks (played by Lynne, Mann and other studio musicians) were sequenced with the original in Studio Vision to see what the final product might sound like.

The final pre-produced tracks were then sent back to McCartney’s England studio on DAT with Lennon’s voice and piano in the left channel, a click track in the right channel (Ringo used the click to add live drums).

Ringo: Jeff Lynne did a great job putting it into time and cleaning it up. Only then could we begin overdubbing.

Paul: Once that had been done we were able to play with it because John was now perfectly in time and there were just little gaps where he’d sped up or gone out a bit. After that we did acoustic guitars and I learned John’s piano part. I’d been studying it a little bit the week before we did the session, and Jeff Lynne had studied it very hard and showed me one or two interesting little variations that John had put in there, that I hadn’t picked up. Then I played it – John and I had very similar piano styles because we learned together – which meant that we now had a voice and a piano separate and could get control over them. Then I put the bass on, which I kept very, very simple: I didn’t want to do any of my trademark swoops or get it too melodic, I just wanted to anchor the piece. I did one or two little tricks but they’re very subtle, like I used my five-string bass, which has got a very low string on it, and saved the low string till the tune does a big key change in the solo, and it really lifts off there. So instead of doing the same bass note I went right down to my second lowest note on the instrument. Then Ringo did some great drumming on it, and Jeff Lynne – being very, very precise – made sure that every single snare was exactly correct and he and the engineer Geoff Emerick got a really great sound.

About the recording location

One of the reasons for the secrecy of those sessions may have been safety. One of the effects of John’s death was that the three remaining Beatles became highly concerned about security matters. Any advance announcement that the group were getting together, even ‘behind closed doors’, would have brought out not only hoards of fans and press photographers, but it would also have been an invitation to any nutter who personally considered George, Paul and Ringo targets.

We agreed to do it at my studio because this is really the only studio that was up and running. I’d been working here regularly so it was all cleaned and ready to go and in full working order. Also, because my studio is slightly off the beaten track – off the Beatle track! – it meant that we’d have privacy. And the press were doing a lot of talk at the time – “It’ll be in Abbey Road” – and we figured they’d be watching places like that. So this became the perfect place to do it and we were very lucky both the times we did it: we didn’t have anybody notice that the guys were here, and I accommodated them all locally so the word didn’t get out too much.

Paul McCartney

Paul: Before the session we were talking about it, and I was trying to help set it up, because we never even knew if we could be in a room together, never mind make music together after all these years. So I was talking to Ringo about how we’d do it, and he said it may even be ‘joyous’. We’d not met for a long time, and the press didn’t bother us because nobody guessed we’d be down there.

About the making-of of Free As A Bird

George, Paul and Ringo were adamant that analogue equipment and die-hard techniques should be used wherever possible. The Beatles experimented on several of the songs Yoko had given them (whether such experiments were actually recorded is unknown) before deciding to focus their attentions on Free As A Bird.

Paul: We just started listening to the cassette, which, as you know, was just a mono cassette with John’s voice and his piano locked in. Anyone who knows anything about recording knows that, for a mix, you try to isolate the voice and the piano on separate tracks to give yourself a bit of control. But we had a fixed tape. First of all, George and I tried to put some acoustics on, and play along with it as it stood because we wanted to be as faithful as possible to the original. But because he was doing a demo John went out of time a bit. Unless you’re working to a click track you don’t concentrate on tempo when you’re doing demos. And because he was trying to find the song on the demo the middle-eights weren’t filled out, lyrically. His vocal quality was nice and he’d put a funny phasing effect on, which there was no getting rid of, but it was a nice effect actually, very Sixties, very evocative. I think it’s one of the things that gives the record a nostalgic feel. But eventually, because George and I had to keep looking at each other and giving signs through our eyes, like “he slows down here, he speeds up here”, it became difficult. It became quite annoying to try and keep up with the speed changes.So it was decided that we had to take another approach. We had to isolate John’s voice as best we could and then lay it back in on the tape to a click track that would not be heard on the record but would be strict tempo. Jeff Lynne and the engineers did that.

McCartney says there was some tension between him and Harrison when it came time to write a few new lines for the song but it passed quickly.

Paul: When we were working on Free As A Bird there were one or two little bits of tension, but it was actually cool for the record. for instance I had a couple of ideas that he didn’t like and he was right. I’m the first one to accept that, so that was OK.

Lennon had left one half-finished verse behind: “Whatever happened to/the life that we once knew?” George and Paul finished it off and took turns singing the first new verse in decades: “Can we really live without each other?/Where did we lose the touch?/It seemed to mean so much/It always made me feel so…“

Paul: John hadn’t filled in the middle eight section of the demo so we wrote a new section for that, which, in fact, was one of the reasons for choosing the song; it allowed us some input, he was obviously just blocking out lyrics that he didn’t have yet. When he gets to the middle he goes, ‘Whatever happened to / The life that we one knew / Woowah wunnnnn yeurrggh!’ and you can see that he’s trying to push lyrics out but they’re not coming. He keeps going as if to say ‘Well, I’ll get to them later’. That was really like working on a record with John, as Lennon/McCartney/Harrison, because we all chipped in a bit on this one. George and I were vying for best lyric. That was more satisfying than just taking a John song, which was what we did for the second, Real Love. It worked out great but it wasn’t as much fun.

George: If you hear the original version you know that John plays very different chords changes in it as well. Historically, what we’d say would be, ‘Well, hang on, I’m not too sure about that chord there, why don’t we try this chord here?’ So we took the liberty of doing that, of beefing the song up a bit with some different chord changes and different arrangements.

Paul: It was the nearest I was ever going to get to writing with John again.

Soon, Lennon’s high, wavering voice was in their headphones. ‘Free as a bird / It’s the next best thing to be / Free as a bird / Home, home and dry / Like a homing bird I’ll fly‘

Paul: It was very good fun for me to have John in the headphones when I was working, it was like the old days and it was a privilege.

Ringo: We were all hanging out together in the studio, but we didn’t do it like we used to. Back then, the four of us would just kick in and get the backing track. We couldn’t do that.

By now, John’s original mono cassette had been expanded into analogue 48 track form. Ringo started the song off with two beats on snare. George broke in with a bluesy slide guitar riff and continued with a slide solo. The demo was further augmented with George’s and Paul’s acoustic guitars, Paul’s bass guitar and new vocals from George, Paul and Ringo. Paul also doubled the piano part to the point where there wasn’t much left of John’s original playing. Jeff Lynne added harmonizer chorus to that piano to blend it in.

Marc Mann: You can hear a little bit of mid-range color coming in when John sings . . . that’s the piano.

Paul: We just got on with it, and treated it like any old tune the Beatles used to do, fixed the timing and then added some bits. George played some great guitar, we did some beautiful harmonies. What I liked was I played very, very normal bass, really out of the way, because I didn’t want to ‘feature’. There are one or two moments where I break a little bit loose, but mostly I try to anchor the track. There’s one lovely moment where it modulates to C, so I was able to use the low C of the five-string. That’s it, the only time I use the low one, which I like, rather than just bassing out and being low, low low. I play normal bass, and there’s this low C and the song takes off. It actually takes off anyway because a lot of harmonies come in and stuff, but it’s a real cool moment that I’m proud of.

George: We did the total new record, then we just took his voice and we dropped it in every line where we needed it until we built up the lead vocal part.

Lynne: Although a long time has passed since they last recorded as one unit, they worked terribly well together. Being in the control room watching and listening to them interact with each other was fascinating. Paul and George would strike up the backing vocals and all of a sudden it’s the Beatles again. They were having fun with each other and reminding each other of the old times. I’d be waiting to record but I was too busy laughing and smiling at everything they were talking about. It was a lovely, magical time. But it was very scary because it had never been done before and there were no points of reference. What do you do on a Beatles record when the singer’s not there?

Paul: It came to the backing harmonies and George said to me ‘ Jeff is such a big Beatles fan, he’d love to get on this record, he’d just die! Even if he goes ‘hey!’ he can then say he was on it’. And I was a little bit reluctant. I’m a bit sort of precious, a bit private about who’s in the Beatles and we didn’t do too badly on that philosophy. Even when Billy Preston came in I was in two minds. The others were so definite that I went with their thinking, as I always did, because I knew they had right-on opinions. Well, Ringo says ‘You know why ELO broke up? They ran out of Beatles riffs.’ One-off Jeff’s great pride is that he met John once – obviously a huge fan of John’s – and John said ‘I really like all that ELO stuff man.’ That was the highspot of Jeff’s life! He was vindicated. John said it was alright! So we got Jeff on Free As A Bird.

At the time, Ringo was reported as saying that the reunion sessions, which had been planned to last a week, had gone “much better than expected” and had been extended right until the end of the month (where work may also have briefly commenced on Now And Then and Grow Old With Me).

Paul: I am quite proud of it. I think it worked great, it’s actually a Beatles record. It’s spooky to hear John singing lead, but it’s beautiful. People said beforehand we shouldn’t do it, but that kind of focused us up a bit. I thought, fuck you! We’ll fucking show you! It’s fatal if they come out in the papers and say we shouldn’t do it, because I want to do it even more. It was a joyful experience, it was magic, it was a really good laugh to be making music together again. Me and George ended up doing harmonies and Ringo’s sitting in the control room. He says, ‘Sounds just like the Beatles!’ It finally did, really, sound like a Beatle record, and we were becoming more and more convinced that we were doing the right thing.

Ringo: Oh I was shocked, it just blew me away. I don’t know why I didn’t think it is us anyway, but, I just had a moment thereof being far enough away from it to look at it as a real thing. And it’s just like them, it was a mind-blower. It sounds like the bloody Beatles, it sounds like a Beatles track. It could have been recorded in 1967. So much has gone down since those days, twenty-odd years ago, but when I played the track, I thought, ‘Sounds just like them!’ Of course, it does, because we’re on it. Doing this project has brought us together. Once we get the bullshit behind us, we all end up doing what we do best, which is making music!

Paul: It was better when there were three of us than when Ringo said: “Oh I’ve done my bit” and left me and George to do it. Me and George, as artists, we had a little bit more tensions. But I don’t think that’s a bad thing. It was only as a normal Beatles session; you’ve got to reach a compromise.

There are banks of Harrison/McCartney harmonies which support the wordless Lennon vocals, and a majestic Harrison solo that leads the track from a Starr drumbreak to the end of the song.

Paul: We pulled it off, that’s the thing, and I don’t care what anyone says. We could work together. We did a bit of technical stuff on tape, to make it work, and Jeff Lynne was very good. We had Geoff Emerick, our old Beatle engineer; he’s solid, really great. He know how Ringo’s snare drum should sound.

The end of the track features Lennon muttering the old George Fromy catchphrase “Turned out nice again” to tie in with some ukulele playing Harrison had taped for the outro.

Paul McCartney: There is real magic going on. On the end of ‘Free As A Bird’, just for a joke – in case people were thinking, “God, they really mean it, this is so serious, this isn’t like all their other records, this is serious homage” – we re-entered with the drums, then George did his George Formby stuff on the ukulele and then, to even take it one stage further, we put in something backwards. We got the guys at the film production office to find a clip of John talking – we gave them a certain phrase to look for, which I’m not giving away – and then we put it in backwards, just as a little joke, a bit of fun that ties in with the ending. Anyway, the incredible thing is, the other day Eddie [Klein, Paul’s studio manager] was working on the tape and he said, “Paul, listen to this” and he played it to me and, I swear to God, the backwards stuff says, “Made by John Lennon”. None of us had heard it when we compiled it, but when I spoke to the others and said “You’ll never guess…” they said, “We know, we’ve just heard it too”. They’d heard it, independently. And I swear to God, he definitely says it! We could not in a million years have known “what that phrase would be backwards. It’s impossible. So there is real magic going on. Hare Krishna!

Geoff Emerick: We hadn’t seen each other or been together in 25 years, and suddenly we were all working like before. The old magic was there instantly.

Paul: And there was a kind of crazy moment, thinking, oh yeah, ’cause, not having done it for so long, you become an ‘ ex-Beatle ‘. But of course, getting back in the band and working on this Anthology, you’re in the band again. There are no two ways about it. And it was good, it was good being them again for a little while. We work well together, that’s the truth of it, we just work well together. And that’s a very special thing. When you find someone you can talk to, it’s a special thing. But if you find someone you can play music with, it’s really something, y’know.

George: It was interesting to actually get back together. For Ringo, Paul, and I, we’ve had the opportunity to let all the past turbulent times go down the river and under the bridge and to get together again in a new light. I think that has been a good thing, it’s like going full circle, and I feel sorry that John wasn’t able to do that, because I know he would have really enjoyed that opportunity to be with us again.

Most of the track was completed by the end of February with the addition of George’s closing guitar part.

Paul: I was worried because it was going to be George on slide. When Jeff suggested slide guitar I thought (dubiously), it’s My Sweet Lord again, it’s George’s trademark. John might have vetoed that. George started to work on his guitar parts, and he did a secondary guitar part, between a lead and a rhythm, sort of arpeggio rhythm you’d have to call it. He came up with some nice little phrases there which are very subtle on the record: I tend to hear them about the third time through. And then finally he came up with his slide guitar. I told Jeff Lynne that I was slightly worried about this because I thought it might get to sound a little bit like My Sweet Lord or one of George’s signature things. I felt that the song shouldn’t be pulled in any way, it should stay very Beatles, it shouldn’t get to sound like me solo or George solo, or Ringo for that matter. It should sound like a Beatles song. So the suggestion was made that George might play a very simple bluesy lick rather than get too melodic. And he did: what he played was almost like a Muddy Waters riff. And that really sealed the project. I thought – I still think – that George played an absolute blinder because it’s difficult to play something very simple, you’re so exposed. But it was fantastic and Jeff Lynne and Geoff Emerick got a great sound on him. In fact, he got a much more bluesy attitude, very cool, very minimal, and I think he plays a blinder. Free As A Bird is really emotional. I’ve played it to a few people who’ve cried, because it’s a good piece of music and because John’s dead. The combination of that can be emotional. But I love that. I don’t have a problem with something that grabs you by the balls so you’ve gotta cry. I rather respect that. We did the end bit, put little extra vocal things on that, and then the ukuleles, which was a tip of the hat to George Formby, whom George is particularly enamoured of. And I like George Formby a lot too, he’s a great British tradition – and John’s mum, Julia, used to play the ukulele so I suppose there was a point of contact there too. And then we got the phrase of John’s to turn backwards, laid it into the mix and thought, “That’s it, it really sounds like a Beatles record.” And so that was it

George: Free As A Bird does sound like the Beatles, only a more modern version. But we went through a lot of changes musically in the 1960s so it’s hard to actually put your finger on what was the Beatles sound. When you say it sounds like the Beatles, people may expect it to sound like 65 or 68. It’s very similar in some respects to Abbey Road because it has the voicing, the backing voices like Because. But the whole technical thing that has taken place between 1969 and 1995 is such that, you know, it sounds a lot more like now.

Paul: No, we didn’t go “We’ll go for the Beatles circa 1967.” It was the Beatles now.

Julian Lennon: I heard the song for the first time when I was last in New York visiting Sean and Yoko. It’s a great song. I love it. Although I must say I find it hard to hear Dad’s vocals.

Paul: When George Martin heard it he was very pleased with it, so that was nice.

George Martin: They stretched it and compressed it and put it around until it got to a regular waltz control-click and then they were done. The result was that in order to conceal the bad bits they had to plaster it fairly heavily so that what you ended up with was quite a thick homogeneous sound that hardly stops.

The Beatles rounded off with a trip to the local pub and a visit to Paul’s neighbour, Spike Milligan.

Paul: When we’d done it, I thought, we’ve done the impossible. Because John’s been dead and you can’t bring dead people back. But somehow we did – he was in the studio.

George: We always said the Beatles was us four and if ever one of us wasn’t in it then it’s not the Beatles, and the idea of having John as the singer on the record, it works, it is the Beatles. There was talk about us doing stuff on our own but I have no desire really to do a threesome.

When the Anthology DVDs were released in 2003, some video footage from these inital Free As A Bird sessions was included on a bonus disc (it’s easily differentiated from the later Real Love footage as George has no beard at this point). The group can be heard rehearsing the song and discussing the chord structure.

Paul: The only recording session I’ve ever written about was Free As A Bird. It was an exciting week and shortly afterwards I went on holiday to America. On the plane I wrote down what had gone on at the session. Just to remember the facts really, before they were forgotten.

From The Beatles Book, N°216, April 1994:

Besides the work on John’s material, those close to the sessions report that Paul, George and Ringo have purely been recording (as promised) “incidental music” for the Anthology video series. The initial phase of recording was completed by the end of February, after which Paul went on a trip to Jamaica. The Beatles’ reunion may be the subject of worldwide speculation, but the Beatles themselves clearly aren’t going to let the project get in the way of their family holidays!

Jeff Lynne, who to that point had already worked with George Harrison and Ringo Starr on solo projects, would later produce McCartney’s Flaming Pie project.

Last updated on September 30, 2020

Songs recorded

1.

2.

Written by John Lennon

Recording • It is believed the three ex-Beatles experimented on the other Lennon demos during those sessions.

3.

Written by John Lennon

Recording • It is believed the three ex-Beatles experimented on the other Lennon demos during those sessions.

4.

Written by John Lennon

Recording • It is believed the three ex-Beatles experimented on the other Lennon demos during those sessions.

Staff

Musicians

- Paul McCartney:

- Keyboards, Acoustic guitar, Vocals, Piano, Bass

- Ringo Starr:

- Vocals, Drums

- Jeff Lynne:

- Guitar, Harmony vocals

- George Harrison:

- Vocals, Acoustic guitar, Ukulele, Electric slide guitar

Production staff

Going further

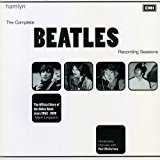

The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions • Mark Lewisohn

The definitive guide for every Beatles recording sessions from 1962 to 1970.

We owe a lot to Mark Lewisohn for the creation of those session pages, but you really have to buy this book to get all the details - the number of takes for each song, who contributed what, a description of the context and how each session went, various photographies... And an introductory interview with Paul McCartney!

Eight Arms to Hold You: The Solo Beatles Compendium

We owe a lot to Chip Madinger and Mark Easter for the creation of those session pages, but you really have to buy this book to get all the details!

Eight Arms To Hold You: The Solo Beatles Compendium is the ultimate look at the careers of John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr beyond the Beatles. Every aspect of their professional careers as solo artists is explored, from recording sessions, record releases and tours, to television, film and music videos, including everything in between. From their early film soundtrack work to the officially released retrospectives, all solo efforts by the four men are exhaustively examined.

As the paperback version is out of print, you can buy a PDF version on the authors' website

Contribute!

Have you spotted an error on the page? Do you want to suggest new content? Or do you simply want to leave a comment ? Please use the form below!