Barry Miles and Steve Abrams meet Paul McCartney to discuss a campaign against drug laws

About

John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, one of the co-founders of the underground newspaper International Times, was arrested for possessing cannabis in December 1966. He was sentenced to 9 months in prison on June 1, 1967.

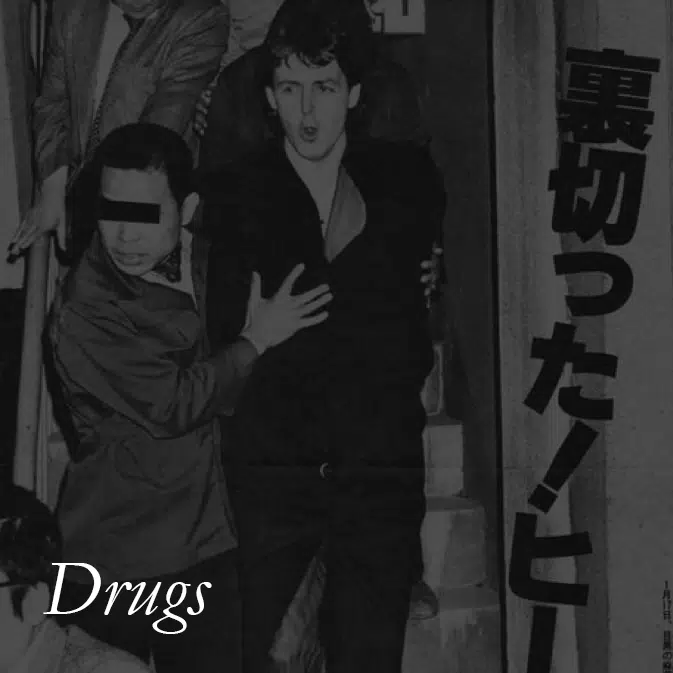

The next day, on June 2, Barry Miles, the other co-founder of International Times and a friend of Paul McCartney, contacted him to seek his support in organizing a petition for reforming the laws against marijuana. Paul promised that the Beatles would finance an advertisement in The Times newspaper condemning the existing laws against marijuana.

On June 3, Barry Miles and drug researcher Steve Abrams visited Paul in his London home to discuss some details. These discussions led to the publication of a full-page advertisement titled “The law against marijuana is immoral in principle and unworkable in practice” in The Times on July 24, 1967.

An emergency meeting of Hoppy’s friends was called the next day in the back room of the Indica Bookshop. There were dozens of people present […], but no one had any constructive ideas except Steve Abrams, founder of the drugs-research organisation SOMA. Steve was a tall American, originally from Beverly Hills but now in possession of a perfect Oxford accent. He was enormously knowledgeable about drugs and the laws pertaining to them. […]. In order to bring the whole issue of soft drugs and the law into the public debate, he proposed running a full-page advertisement in The Times. Since Steve was prepared to organise this, the idea was unanimously approved. The matter of paying for the advertisement, however, was not solved. I called Paul McCartney and arranged to take Steve over to meet him the next day.

Steve met me at the bookshop and we took a cab to Cavendish Avenue. The French windows in the living room were wide open and a slight breeze stirred the warm air in the room. Psychedelic posters lined the hallway and the drum head with ‘Sgt Pepper’ written on it was on the wall over the settee. An Indian sarod leaned drunkenly in the middle of the carpet where Paul had left it. Steve was well prepared and had the idea very thoroughly worked out in his head. He told Paul the names of some important people he thought would sign the advertisement. Paul said the Beatles would pay for the ad and that he would arrange for all of the Beatles and Brian Epstein to put their names to it. As we left the living room, Paul gave Steve a copy of Sgt. Pepper from a big pile on a table by the door. Steve later wrote, “Unless my memory is playing tricks on me, McCartney thrust a copy of Sgt Pepper into my hands and said, ‘Listen to this through headphones on acid.'”

Barry Miles – From “In The Sixties“, 2003

From Wikipedia:

Stephen Irwin Abrams (15 July 1938 in Chicago, Illinois – 21 November 2012) was an American scholar of parapsychology and a cannabis rights activist who was a long-standing resident of the United Kingdom. He is best known for sponsoring and authoring the full-page advertisement petitioning for cannabis law reform which appeared in The Times on 24 July 1967. […]

Oxford and the founding of SOMA

Abrams was an Advanced Student at St. Catherine’s College of Oxford University from 1960 to 1967. He headed a parapsychological laboratory in the university’s Department of Biometry, investigating extrasensory perception.

In January 1967, the content of an article by Abrams “The Oxford Scene and the Law”, intended as a contribution to a forthcoming book The Book of Grass was republished, without his permission, in The People Sunday newspaper. The article was a balanced reasoning on the social and personal effects of cannabis use and its repression. The article observed that under current laws cannabis users were punished more severely than heroin users. Cannabis smoking was regarded as a crime but heroin addiction was treated as an illness. Doctors had the right to prescribe heroin. The Court might send a cannabis smoker to prison and send a heroin user to a doctor. Presented in the sensationalist manner for which the paper was known, the story emphasized Abrams claim that 500 of Oxford’s student body were cannabis users. The story spread. Headlines like “Smoke more pot. It’s safer than beer”, appeared in the popular press. On 1 February, the same day as long clarifying letter from him was printed in The Daily Telegraph, Abrams announced, via the pages of student newspaper Cherwell, the formation of SOMA, an acronym for the Society of Mental Awareness, as a drug research project. Two weeks later, on 15 February 1967, Abrams gave evidence before the University Committee on Student Health, which agreed to pursue his suggestion that the Home Secretary be prevailed upon to institute an inquiry. After the committee’s published report received national press coverage, on 7 April 1967 home secretary Roy Jenkins appointed a “sub-committee on hallucinogens” to be chaired by Baroness Wootton to report to the Advisory Council on Drug Dependence, itself appointed four months earlier in December 1966.

Protests and organizing The Times advertisement

Public awareness had been increased by the February arrests of Keith Richards and Mick Jagger on drug charges. In the midst of Abrams campaign in Oxford, on March 1, 1967, activist Hoppy had organized a happening in Oxford that had turned into an impromptu “pot protest”. Swelled by rowdy participants from Oxford Polytechnic’s rag week, the event gained national coverage. Hoppy himself, a member of the editorial board of the underground newspaper International Times, had been arrested for cannabis possession the previous December, after police raided his London flat. Although the amount was small, he had a previous conviction, so this was a serious matter. Out on bail, Hoppy went on to organize the massive 14 Hour Technicolor Dream multimedia event at Alexandra Palace on April 29. In his drug case – despite having no defense – he insisted on pleading ‘Not Guilty’, elected for trial by jury, and lectured the court on the iniquity of the law. Needless to say he was found guilty. On June 1, 1967, he was sentenced to 9 months in prison by a judge who called him a “pest to society”. He rapidly became a cause célèbre and a ‘Free Hoppy’ movement was born.

On 2 June, at a gathering of Hoppy supporters, Abrams launched the idea of a SOMA advertisement in The Times petitioning for reform. The idea was that this could serve the double purpose of raising awareness of Hoppy’s case and to influence the Wootton Committee, who everyone thought was going to legalise cannabis use. Barry Miles introduced Abrams to Paul McCartney who was persuaded to anonymously donate the £1,800 cost. McCartney had recently blurted to the press about his LSD use. Controversy raged over lyrics suggestive of drug use on the Sgt. Pepper’s album, released on 1 June . After word got out of his backing of the advertisement his support wavered. Abrams was able to convince McCartney that associating The Beatles with the cannabis cause could serve to direct all the attention in a positive direction. The space was booked for The Times of Monday 24 July 1967, and Abrams set about recruiting signatories.

He was helped by circumstances. On 29 June 1967, the sentencing of Richards and Jagger to lengthy jail sentences precipitated spontaneous protests on Fleet Street outside the offices of the News of the World, widely seen as having instigated the police action after Jagger had threatened them with a libel action over drug allegations earlier in the year. The protests met with violent police responses, including the use of dogs. Jagger and Richards were freed on bail the next day, Friday 30 June. At midnight that day the entire crowd at underground club UFO and many others, including Abrams, again marched to the News of the World to demonstrate. After a third night of protests, again met with police violence, Abrams was among those whose picture appeared on the News of the World‘s front page on 2 July.

The next big event was a “Legalize Pot Rally” at Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park on Sunday 16 July. A permit having been refused for a larger event, the protesters led by Abrams – and including speakers Allen Ginsberg, Caroline Coon, Stokely Carmichael, Alexis Korner, Spike Hawkins, Clive Goodwin and Adrian Mitchell – split into small groups in this famous haven of free speech. Again wide publicity was gained, and International Times commented “Vast publicity for legalize pot rally. Steve Abrams appears on television with amazing regularity”

The Times advertising department were still apprehensive. Abrams speculated around 1988 that, if it were not for the furor over the Rolling Stones case – which included the famous William Rees-Mogg editorial Who breaks a butterfly upon a wheel? on July 1 – they would have balked. As it was, at the last moment they demanded payment in advance. Abrams called The Beatles office Apple and assistant Pete Brown came up with a personal cheque to save the day.

A week after the advertisement appeared, on 31 July 1967, Keith Richards’ cannabis conviction was quashed, and Mick Jagger’s prison sentence (for possession of amphetamine tablets) reduced to a conditional discharge.

The Times advertisement

The advertisement appeared in The Times on 24 July 1967. A full page, it stated: ‘The law against marijuana is immoral in principle and unworkable in practice.’

The advertisement went on to present medical sources asserting the harmlessness of cannabis, and recommended a five-point plan:

- The government should permit and encourage research into all aspects of cannabis use, including its medical applications.

- Allowing the smoking of cannabis on private premises should no longer constitute an offence.

- Cannabis should be taken off the dangerous drugs list and controlled, rather than prohibited, by a new ad hoc instrument.

- Possession of cannabis should either be legally permitted or at most be considered a misdemeanour, punishable by a fine of not more than £10 for a first offence and not more than £25 for any subsequent offence.

- All persons now imprisoned for possession of cannabis or for allowing cannabis to be smoked on private premises should have their sentences commuted.

The sixty-five signatories comprised leading names in British society, including Nobel Laureate Francis Crick, novelist Graham Greene, Members of Parliament Tom Driberg and Brian Walden, photographer David Bailey, directors Peter Brook and Jonathan Miller, broadcaster David Dimbleby, psychiatrists R. D. Laing, David Cooper, and David Stafford-Clark, the critic Kenneth Tynan, scientist Francis Huxley, activist Tariq Ali, and The Beatles, along with their manager Brian Epstein.

The advertisement was controversial, receiving both public support and establishment condemnation. It was discussed in Parliament. At the 1967 Tory party conference, the Shadow Home Secretary, Quintin Hogg said he was “profoundly shocked by the irresponsibility of those who wanted to change the law“, describing their arguments as “casuistic, confused, sophistical and immature.“

The Wootton Committee’s Report, when submitted in November 1968, specifically cited the advertisement’s influence on its proceedings, noting that the advertisement’s claim that “the long-asserted dangers of cannabis are exaggerated and that the related law is socially damaging, if not unworkable’, had caused the committee to “give greater attention to the legal aspects of the problem” and “give first priority to presenting our views on cannabis.” The Report vindicated much of the advertisement’s position, stating “the long-term consumption of cannabis in moderate doses has no harmful effects.”, that cannabis was “no more dangerous than alcohol” and that prison only be recommended for cases of “organised large-scale trafficking” and all other offenders be given, at the worst, suspended sentences. The Home Secretary of the day, James Callaghan denounced the Report, claiming its authors had been “overinfluenced” by the “lobby” responsible for “that notorious advertisement.” However he later quietly reversed his position, and many of the Report’s recommendations became law in 1971 – ironically enacted by Hogg who, after a change of government, had taken over as Home Secretary. […]

Last updated on May 9, 2024