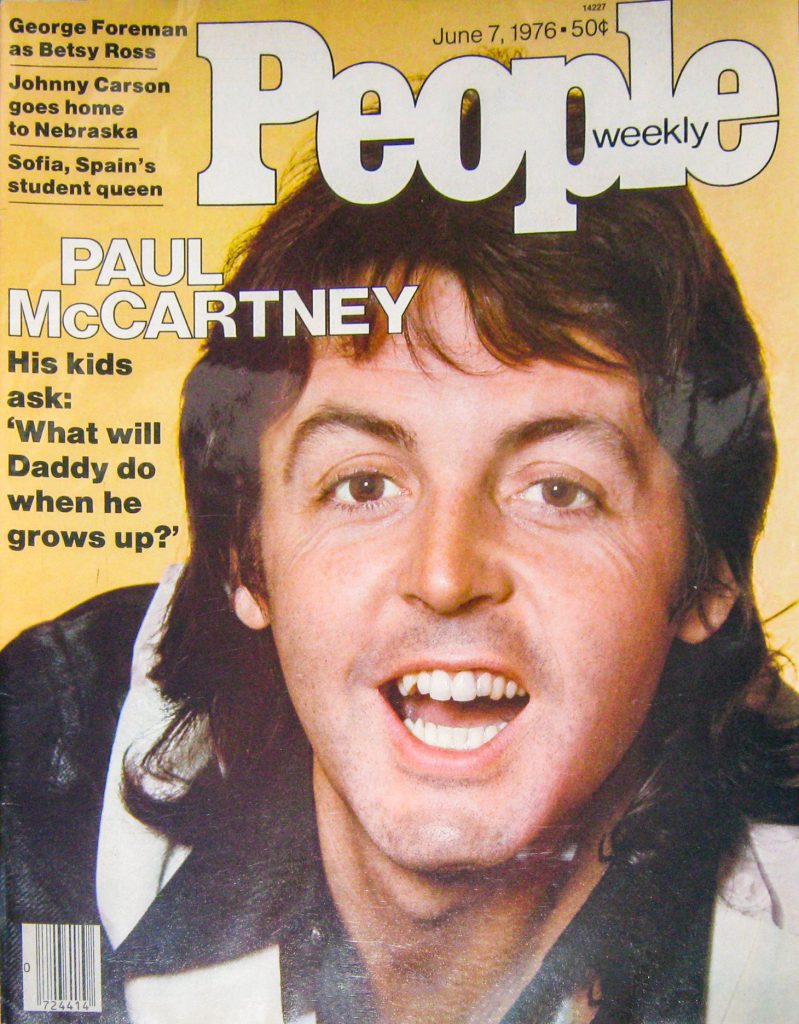

Interview for People Weekly • Monday, June 7, 1976

Daddy McCartney

Interview of Paul McCartneyInterview

Paul McCartney: While I accept that I was with a group called the Beatles —they were very famous — now I’m in Wings. Beatle is really just like a nickname now.

Paul: I love bein’ a parent— I never realized how much kids remind you of your own youth.

Linda McCartney: Our kids keep asking, “What is Daddy going to do when he grows up?”

—On tour, May 1976

Paul McCartney is two-thirds through his first American tour in a decade, having, enervatingly, to explain away the continuing nonreunion of the Beatles, not to mention the presence of his wife, Linda (on vocal harmonies and keyboards), with Wings. Most troubling, Paul, at 33, has to grapple with the crucial metaphysical puzzle of his own and his kids’ generation: not life after death, but is there rock ‘n’ roll after 30?

“The Beatles always used to say, ‘Ooof, can’t imagine us rockin’ when we’re 30, can you?’ But bein’ 30 is really just like bein’ 25, or even 18. Unless, of course,” Paul adds puckishly, “you’re the type of 30 who settles down and grows a corporation.” And, alas, that’s McCartney’s dilemma. He’s the most commercially successful of the Beatles since the 1969 bust-up (seven LPs, all at least gold including his latest single, “Silly Love Songs”, and accompanying LP, Wings At the Speed of Sound). “Paul’s very worried,” says John Eastman, his brother-in-law and lawyer, “about losing his fans because of being too Establishment. He doesn’t want to be a businessman, but he really didn’t have any choice.” McCartney’s present 21-city tour is the monster rock event so far in 1976, an assured $4 million sellout. But, says Paul exuberantly, “Here I am, 33, and I still feel I know what it’s like to be 13—not knowin’ anything, but thinkin’ I’ve got the hang of it all—and I’m still rockin’ at heart.” McCartney’s two-and-a-half-hour shows make his point. Not only is his voice still an instrument of remarkable range and precision, but Paul can also stomp and stalk onstage like a power-riffing punk-rocker half his age. Simultaneously, he transforms Wings’ hits (too often innocuous on records) into thrilling and gutsy rock on stage. But it is McCartney’s singing of Yesterday, with acoustic guitar, in mid-concert—the last of five Beatles songs worked into every show—that is transcendent. The song is received, night after night, with long and thunderous ovations—as other fans simply stand in tearful silence. This seems to be McCartney’s subtle—if unwitting—way of acknowledging the awesome emotional power of the Beatles’ past, while unburdening himself, for now, of its crushing weight. It is not really just a nickname—that’s a canard—but McCartney’s canonization and a curse. Paul is grudgingly resigned to questions about a Beatles reunion for the rest of his life (“Great, isn’t it?” he grouses). He has prepared nonanswers for this tour, the most optimistic of which runs, “No one wants to shut any doors permanently, but by the same token, no one wants to start any rumors.” “It was a tough act to follow,” he admits, referring to the schism, after a recent show. “I felt a bit panicky for a few years at the idea of losing my job, and a plum of a job at that. You better believe it was hard to get going on my own after we split.” (Bringing Linda, the so-called “Park Avenue Groupie,” into Wings also didn’t exactly ease his way with the critics.) Nothing about the Wings tour suggests that McCartney is a roadaholic. On the contrary, his monogamous life-style makes clear that he enjoys being a father and is still decidedly sane after all these years. The son of a cotton salesman and a midwife from Liverpool, McCartney’s views of family were shaped as a boy, in his own tight-knit home. Paul reports that he and Linda have left the children outside of their extended family only “one or two nights” in their seven-year marriage. He has adopted Heather, now 13, by Linda’s first husband (a Princeton-educated geologist), and they have two of their own, Mary, 6, and Stella, 4. An enormously energetic and disciplined man, McCartney plans child-care arrangements as meticulously as his tours. Leaving the kids at home in London, or on their farm in Scotland “with totally strange influences on them—people teachin’ them their ways,” was unthinkable. “Our kids go with relatives for a few days,” he says, “and come back with sweets comin’ out their ears, Coke on their teeth and talkin’ back: ‘I don’t WANNA do it.’ ” But in no time, reports Paul, with a mock scowl, “they get back to the old working-class way of ‘You bloody WILL do it.’ This is the way I grew up and it still works—acting on that tribal instinct. Now Dr. Spock has come out years later and said he was afraid he was wrong—the kids are running away with it. Well, that’s what I could have told him right at the beginning. If the kid doesn’t respect the parent as the boss of the house, you’re in for trouble.” (Actually, McCartney has—as Spock says of others—misunderstood him.) “We don’t believe in nannies,” says Paul, “because the kids end up callin’ them Mommy.” (The McCartneys do travel with a housekeeper, though, and a tutor to help Heather with her studies.) Even the tour has been scheduled to ensure at-home surroundings. They rented a house in Dallas, stayed with relatives of Linda’s late mother in Cleveland, and, though a hotel is their Manhattan base, they frequently visited the Long Island or in-town quarters of her brother and dad. “Most people,” says Linda, who grew up in the swanky suburb of Scarsdale, “don’t see their kids this much because fathers work, kids are in school, mothers are off playing golf. On weekends,” she observes, “everyone is usually too tired.” Never the McCartneys. In his free time Paul likes to teach Mary reading (his own favorites: sci-fi and comics). A decade has passed since Paul co-wrote Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the catalytic musical force in the late ’60s cultural upheaval. Time, and parenting, have made him mellower, more optimistic, he says. “Lots of people in suburbia got some money, went a little above themselves and bought furniture you couldn’t sit on. Livin’ in houses like that—that’s what everyone was revolting against. The Beatles probably encouraged it, that revolt, but we didn’t start it. It was all goin’ to happen anyway. We just happened to be in the fore—along with the Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan, the poet of it all. “But the ’60s parent-gap thing is the ’70s parent thing, the ’50s and the ’40s, too. We thought the ’50s were dead, but Heather’s here to prove they aren’t.” Adds Linda, a self-described Transistor Sister from that period herself, “Heather and her friends are all so laid back and cool. Very Fonzie.” The McCartneys, like their dual-citizen kids, are bicultural—he prefers To Tell the Truth and reruns of The Munsters. “Now, I’m more mature,” notes Paul. “I’m not happier than I was as a single man with the Beatles. But as happy, in a different way. I used to wake up to chicks and old drinks,” he reflects, “but that horror has been removed from my life. Now,” he smiles, “it’s a whole other thing. I have my own kids in the morning when I wake up.” But what, to answer those kids’ question, is Paul going to do when he grows up? “I keep telling them, a sailor or something,” he quips. “If it gets to be where I feel a bit decrepit and I can’t rock,” he says, “well, I’ll go to the kind of fruity music I also like. Cheek to Cheek is one of my favorites. I might go on till I’m 90 and just slow the songs down a bit. I was talking to John [Lennon] just before the tour began,” continues Paul, “and he said, ‘Sooner you than me.’ I understand John’s big ambition is to write the great classical novel. Tony Curtis wants to be a great painter.” As for Paul McCartney, he eyes his guitar and his family, and observes: “I think I am what I want to be.”

Last updated on September 1, 2020