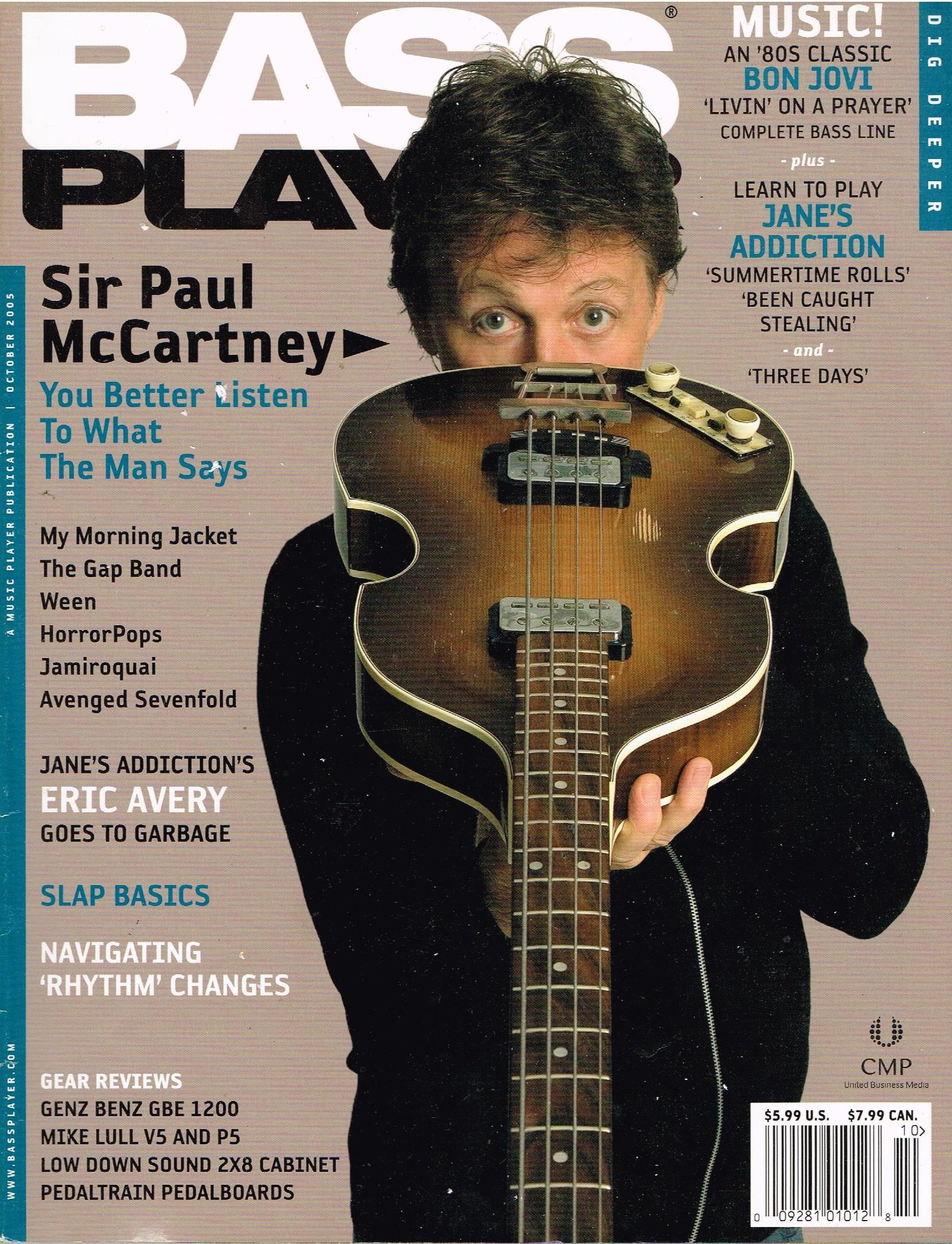

Interview for Bass Player • October 2005

This image is a cover of an audio recording, and the copyright for it is most likely owned by either the publisher of the work or the artist(s) which produced the recording or cover artwork in question. It is believed that the use of low-resolution images of such covers qualifies as fair use.

- Album This interview has been made to promote the Chaos and Creation in the Backyard Official album.

Interview

He was a member of the most famous band ever, he’s one of the most influential first-generation bass guitarists, and he constitutes one half of the most successful songwriting team in history. But the buzz about Sir Paul McCartney is true: He’s one of us! Not only is Paul proud to be a bassist, he’s as down-to-earth as the thumper in your local garage band or pub. Warm and friendly and quick with a witty anecdote or self-barb, McCartney cracks the same jokes as our bandmates—except his are about rock iconography. He expresses the same struggles and doubts we have about trying to finish a song or a bass line; he just happens to be talking about “Hey Jude” or “Day Tripper.” And when it comes to listening—whether it’s a suggestion from Beatles producer George Martin in the studio, or a Bass Player interviewer on the phone from New York to London—he’s second to none. In fact, it’s that fascination with all things musical that keeps Paul McCartney as wide-eyed and open-eared as the rest of us. His latest CD, Chaos and Creation in the Backyard, is one of his strongest in years; it’s packed with lush mid-tempo meditations and dark-colored, reflective ballads. There’s also an interesting footnote: Paul plays virtually all the instruments, and producer Nigel Godrich [Radiohead, Beck] employs the all-Macca ensemble in much the same way Martin might have himself, back when Abbey Road met “Penny Lane.” Everyone knows a lot about Paul McCartney, but here are the bass essentials: Born in Liverpool on June 18, 1942, McCartney learned his first instrument about 14 years later—a trumpet bought for him by his dad. He soon moved on to guitar, re-stringing it to be left-handed. Shortly after the Beatles formed, in 1960, Paul switched to piano, while the band was performing in Hamburg, Germany. In mid 1961, on a second tour of Hamburg, original Beatle bassist Stuart Sutcliffe informed the others that he was leaving to pursue his art career. By default, McCartney inherited the bass chair; he purchased his first Hofner “violin bass” for the equivalent of $45. Fast-forward as Beatlemania ensued (via his ’63 Hofner and, from Sgt. Pepper on, a ’65 Rickenbacker) until Paul, John, George, and Ringo decided to call it quits in 1970. That same year, McCartney began a solo career (later forming the band Wings) which is now in its 35th year. And while he may not have settled on a bass as easily as during his Fab Four days—he fingered Fenders, Ricks, Yamahas, and a Wal 5-string, among others, before returning to his Hofner—his solo sound zeroed in on the charts to the tune of nine No. 1 singles and seven No. 1 albums. We spoke to Paul (on the eve of a fall U.S. tour) about his new CD and the development of his bass style through the years—a revisit that just so happens to chronicle major changes to the musical landscape.

Q: What led to the recording of Chaos and Creation in the Backyard?

A: I’d been touring with my live band, and I just fancied making a new record so we would have some fresh songs for our upcoming tours. I started writing with that in mind, and when I had enough material, I rang George Martin and asked him if he could recommend a producer. He suggested Nigel Godrich. We got together in the studio and he said, Look, I love your band, but I’d like to try a different direction—I’d like to hear you play some drums, guitar, and piano, in addition to bass. I agreed to try it, but I told him it would be awkward to explain to my band, and he said, “Blame me”—which I did! They were very cool about it; they said we’ll be playing the songs live, anyway. [The band assists on one track.] So that’s how I proceeded. I even ended up playing some recorders and, on “Friends to Go,” an old flügelhorn my dad had given to me. Nigel’s concept really turned the album around and gave it the organic quality it has.

Q: How did having to play all the instruments affect your bass parts?

A: In a way it was kind of helpful, because I knew what the drummer was going to do! I knew what bass drum pattern I had played, as well as the thinking behind it, so it was very handy. One aspect of playing all the instruments—which Nigel instinctively realized—is that the feel is basically the same because it’s all coming from one person, which is interesting. I wouldn’t want to make albums like that forever, but it was enjoyable. Also, we do have other musicians doing the strings and specialty stuff, and Nigel had [L.A. session vet] James Gadson and [Beck sideman] Joey Waronker play drums on a few tracks.

Q: How do you typically write a song?

A: Usually, I start on either piano or guitar. “At the Mercy” is a good example. I was sitting at my piano looking for some interesting chords, and I found these quite dark chords [C7, Daug, D, D(5), D6, Em, and Edim]. From there, I started scatting along to see what came into my head. That’s basically what I do; I find something to vamp on, and then I throw some sort of melody and words against it—even if it’s just wordless syllables. And then a phrase will be there that I don’t necessarily understand at first. In this case, I suddenly heard myself singing, “at the mercy.” That gave me a concept to flesh out the rest of the lyrics with. Then, musically, I contrasted the darker opening section with the happy, Beatles-like melodic section that follows.

Q: How do you typically come up with your bass lines?

A: I just jam it with the song. I’ve always done that. I just play along with the song a few times; hopefully the cream rises to the top and you get a good part. The first thing I do is work out the root notes and see if I can find a little melody in the way I pass from one chord to another. Like, if you have C to A minor, you might come down by the B, or the B and B, or you might go up to the high A through the G. Then I’ll maybe not go to the root at times and try to “defeat” the chord somewhat, and I’ll try other ideas. I’m a melodicist; I like melodies, which I think you can hear in my songwriting. So I always try to get a bit of melody out of the bass part, but not too much—you can get in the way if you do it all the time or play too many notes. You have to be selective, or else the composer can get a bit annoyed. I don’t think George [Harrison] was too pleased with what I did on “Something” at first; I mean, I had to sell it to him!

Q: What basses did you use on the CD?

A: It’s all my little old Hofner. I had laid it to rest quite a few years ago because the intonation was a little out. It wasn’t the world’s most expensive instrument, you know; they don’t have a Hofner Precision! I used to love it in the Beatles, but I put it aside. Then [in 1989] I was doing Elvis Costello’s album Spike, and while we were working on “Veronica,” he asked me to play a bass line on the Hofner. I explained I hadn’t used the bass in a long time, but he talked me into it, and I found I really dug playing it again. Soon after, I happened to see the on-the-roof footage from the Let It Be movie [the Beatles playing on the roof of Apple Records], and I noticed I was playing rather delicately on the Hofner. Because the bass is so light, it encouraged me to play with a light touch and be more adventurous with it. I’d play it more like a guitar, whereas my big, heavy Wal 5-string leads me to play more solid, deep bass. So looking back, the Hofner was a key to my style.

Q: You can hear that on “How Kind of You,” “At the Mercy,” and “Promise to You Girl,” where you use octaves and upper-register passages very effectively. Can you explain how you apply them?

A: It’s just something I love to do and recognize as a sort of signature of mine. I always try it, though sometimes it’s not appropriate. But I’ll always go up the octave and just vroom, vroom, slur into high notes for a few little runs, and then come back down and nail the bass part—and maybe do it again later in the song. The slides and slurs are, as we said, from playing guitar and using some of that approach on my Hofner.

Q: Can you describe your basic technique? Do you do any slapping or muting?

A: I use either a pick or my fingers; I don’t really do any muting or slapping. I’m pretty straightforward. I normally use my thumb and index finger; I use thumb downstrokes when I’m chuggin’ eighth-notes, like on “Fine Line,” which is the first single [and opening track] from the album. It’s a light thumbstroke. You don’t need to bash it—especially on the Hofner—but it still gives a nice, thick sound.

Q: Your use of chromaticism on the verses of “How Kind of You” recalls Motown’s James Jamerson. Was he an influence melodically as well as rhythmically?

A: Oh yes, he was a major influence all around; he was certainly where I picked up a lot of my style. I simply loved all of his bass lines [sings “Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch”]—each one was a gem in itself. I’d have to listen to my old tracks to point out the direct influences, and I’m not a great retainer or analyst of what I do. Really, I just tried to take his ideas to my own place, and he was very inspirational in that way.

Q: Tracks like “English Tea” and “Anyway” typify your trademark use of non-root tones. Let’s trace the development of that.

A: Initially, I think it was from having heard it done in songs before I was a bass player, and wondering, What is happening here? The whole song just changed. The bass player stayed on the I chord when the band went to the IV chord. It’s like he’s holding them up for ransom—that’s cool. That’s when I discovered the power of the bass! Because bass players normally have to follow: We follow the chords, follow the drummer, follow the vocalist, we have a following role. Suddenly, the bass had power! We could dictate the direction of the music and add interest and excitement. From there, I heard it used very effectively by [the Beach Boys’] Brian Wilson, who would have, say, the 7th in the bass. Plus, there were other factors, like my playing piano and guitar, and working out vocal harmonies with the Beatles—all of which involved non-root bass notes. As a device, it can give a song a new lift, a hook nobody intended—and you might find your drummer comes along with you and accentuates it a bit. Ultimately, it’s about looking around and seeing what’s on the horizon that you can pull in and use—but not overuse.

Q: “Jenny Wren” has a fingerstyle-guitar-derived bass line, like the Beatles’ “Blackbird.”

A: That was the intention. I’ve had “Blackbird” on my mind since my poetry book came out [Blackbird Singing, 2001], and I’d read the lyrics at poetry readings. Plus, people are always asking me to show them how the song goes on guitar. Anyway, I had a day off while recording the album at Oceanway in L.A., so I grabbed by guitar and drove up into the canyons to try writing a song. When I got up there and started playing, the idea came to me to revisit the “Blackbird” style, with a two-part melody and bass line on guitar. I finished the song in my kitchen that night, while [my wife] Heather was cooking. Actually, the original genesis for “Blackbird” was a piece by Bach [sings “Bourée in E Minor”]. As kids, George and I used to show off and try to play it as a party piece, and folks would go, Wow, man, you know classical! [Laughs.] Of course we didn’t play it quite right; we left out a few notes, but that mistake became the first line of “Blackbird.”

Q: The lead bass-like openings of “Too Much Rain” and “This Never Happened Before” allude to your famous use of sub-hooks on tracks like “Come Together.” Were you aware of that concept back then?

A: I was, yeah. I love the sub-hook. It’s something I’m very proud of: having been lucky enough to be involved in some great records and to come up with a cool riff like “Come Together” or “Silly Love Songs,” which supports the chords and the melody, while becoming an actual hook. The only trouble is having to play them and sing them at the same time, live! The worst for me was “Day Tripper”; I had to try to sing the high part and play a completely independent riff. You just have to learn each part separately. Once your brain has learned its bit and your hands have learned their bit, and you’ve persuaded them to go off in different directions, you’re on your way!

Q: You’ve said Sgt. Pepper is your strongest bass work with the Beatles.

A: Yeah, probably, right around that period; it was the most inventive. Take a track like “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds,” with the sort of independent bass line that wanders off as its own little tune. And I got away with it—John [Lennon] didn’t tell me off! I think Pepper was a highpoint in many ways: in clothes, in songs, in concepts for albums, as well as in bass playing. I was looking for something different, for somewhere to go, really, that I hadn’t been before—using heavy James Jamerson and Brian Wilson influences. It all came together on that album.

Q: What do you like, bass-wise, from the Wings/solo portion of your career?

A: I always liked “Letting Go” [from the 1975 Wings album Venus and Mars]; it’s very simple, but always nice to play the bass to. And, as I mentioned, “Silly Love Songs” is a good bass tune; it’s fun to sing and play live.

Q: Let’s talk about other bassists. On your own projects you’ve worked with Stanley Clarke, John Paul Jones, Louis Johnson, Nathan Watts, and Herbie Flowers, to name some.

A: All those guys are fantastic. Sometimes I might be looking for a style that I can’t do; particularly in Stanley’s case, it was his slapping [sings a cool slapped rhythm]—and in actual fact we didn’t use that much slapping on the two records he guested on. But I love to work with great musicians, and occasionally, if I’m playing more piano or guitar on a song, I’ll think, It would be nice to get someone else’s take on the bass part. John Paul Jones and I did some film stuff together, he was on Back to the Egg, and he did the live Rockestra shows with me [for UNICEF in London, in 1979]. I’m lucky in that if I make the call these guys will show up!

Q: Do any current bassists catch your ear?

A: There are so many great ones. Pino Palladino and Will Lee come to mind. A lot of today’s bassists are tremendous; I just don’t know their names, or much about them, nor do I get a chance to study them. But there’s a very healthy music scene right now of people playing instruments as opposed to feeding a computer. There are a host of bands coming up with good songs and good musicianship, and I like to see that. My album is just me singing and playing without getting too far-out or gimmicky, and that traditional approach seems to be favored by a lot of artists at the moment.

Q: Apparently, the family of Elvis Presley bassist Bill Black found his original Precision, which they’re going to show you.

A: That’s right. I’ve got his original Elvis stand-up bass, and I’m so pleased with that; [my late wife] Linda bought it for me in Nashville [in 1974]. I did a TV/radio show the other night at Abbey Road to promote my album—which was more like a master class where I spoke to people—and at one point I unveiled Bill’s bass and told some stories about it. And then me and the bass did a version of “Heartbreak Hotel”! When I got the bass, we found an old packet of acoustic guitar strings in it. Bill used to change Elvis’s strings, so our theory is they must have been on one of these big, gold lamé special events, Elvis broke a string, and Bill changed it. So where do you put a string packet in the middle of a posh affair? You post it in the ƒ-hole of the bass!

Q: You’ve explored every shade of rock and pop music, as well as classical and film scoring. Is there anything you want to do musically that you haven’t done yet?

A: Not really. It’s still the same as it ever was; I just love making music, and I want continue making music. I’d really like to find out more about the technical side of what I do, because to me it’s still a mystical process. Otherwise, I just look forward to finding that odd note on the bass or that strange little riff that shouldn’t work but does.

BEATLE BASS MANIA

It’s likely the most prized electric bass guitar in history: Paul McCartney’s 1963 Hofner 500/1 “violin bass,” now known to the world as the Beatle Bass. Present on most Beatles recordings and then semi-retired in the ’70s and ’80s, it has been McCartney’s main bass since the early ’90s, when intonation work was done on it by Mandolin Bros. in Staten Island, New York. According to Keith Smith, McCartney’s technical manager for the past 16 years (he joins Paul’s longtime personal assistant, John Hammell, in tending to everything from Paul’s bass to gear for the entire band and tour), the Beatles set list from their last live show in 1966, which was taped to the side of the Hofner, was removed a few years ago to restore and preserve it. For strings, McCartney favors La Bella Beatle Bass flatwounds, gauged .039, .056, .077, .096. His picks are heavy-gauge oversize Fenders. Other basses in his collection include his ’65 Rickenbacker 4001S (dubbed “Rickey”), a newer Hofner, his Wal 5-string (“I love the sound of the low B, but I’m a 4-string boy at heart; I expect there to be an E on the bottom!”), and Elvis Presley bassist Bill Black’s upright, which boasts a gold-sprayed top, white bindings, and unknown strings.

With his live band (guitarists Rusty Anderson and Brian Ray, drummer Abe Laboriel Jr., and keyboardist Wix), McCartney plays his main Hofner (with the newer Hofner and his ’65 Rickenbacker as backups), as well as his Les Paul and Martin D28 guitars through the following signal chain: His bass or guitar goes through a Pete Cornish custom switching system, with footpedal switches for bass, guitar, sustain, chorus (both for the guitars—he uses no effects with bass), and a Boss TU-12 tuner—plus an input for his Shure UHF wireless system. That goes to his Mesa/Boogie Bass 400+ head (500 watts, 12 tubes), which, for bass, powers older Mesa/Boogie cabinets: a Super 15 (1×15) and a 1516 (1×15, 1×10, 2×6, and a tweeter). His bass sound goes to the house via a mic on the 1×15 cabinet and a custom DI in the Cornish system. Paul prefers to feel the bass, so he often stands in front of his centerstage-located rig, and he keeps a mix of the whole band in his monitors. When McCartney is playing guitar or keyboard (about one-third of a show), bass duties are handled by either Wix on keyboard, or Brian Ray, who will have a new Yamaha bass on this tour.

For the recording of Chaos and Creation in the Backyard, McCartney sent his Hofner through Nigel Godrich’s Ashdown rig: a 500-watt head and a 4×10 cabinet, which Godrich miked with an old Neumann U 47; no direct signal was taken. (One early track was recorded through McCartney’s miked Mesa/Boogie rig.) Paul usually tracked his bass parts after he recorded the initial keyboard or guitar, and the drums.

Last updated on January 11, 2021