Interview for McCall's • Wednesday, August 1, 1984

The Alarmingly Normal McCartneys

Interview of Paul McCartney

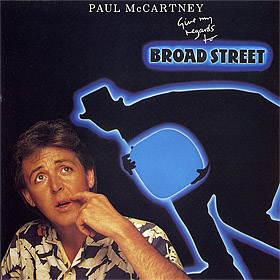

This image is a cover of an audio recording, and the copyright for it is most likely owned by either the publisher of the work or the artist(s) which produced the recording or cover artwork in question. It is believed that the use of low-resolution images of such covers qualifies as fair use.

- Album This interview has been made to promote the Give My Regards To Broad Street (CD version) Official album.

Interview

Yes, Paul McCartney is still very cute. Rumors of his imminent old age, his loss of adorableness, have been greatly exaggerated. Those large puppy-dog eyes, that cherubic face with the permanently quizzical expression, are the same as they were in 1964 when my friends and I argued vehemently over which Beatle really was the fabbest of the four, Paul usually winning hand down. Now I am talking to The Cutest Man In The World and A Legend In His Own Time, and the thing I am struck by is that he is fiercely ordinary. The boy next door — who just happens to have sold 100 million albums and 100 million singles (a Beatles entry in the Guinness Book of World Records) — who is one of the richest men in the world and whose face is as recognizable as the Pope’s.

We are at Elstree Studios outside London, where Star Wars was made, and where Paul is dubbing his film Give My Regards to Broad Street, to be released in the next few weeks. The movie, which he wrote and stars in, is describe by his company as “a musical fantasy drama in the tradition of The Wizard of Oz.”

“The Wizard of Oz?” I ask as Paul offers me half his fruit salad and some red wine. “That’s jut the director’s way of explaining the spirit of the music,” he explains, “the way you say Star Wars is a ‘sci-fi epic.’ There’s a dream quality to it, but there are no Munchkins,” he assures me. “And I don’t play Dorothy.” While no one would question his ability to write a score, they did question whether he could write a film. Undaunted, he interviewed Britain’s top playwrights, then decided he would do it himself.

Paul McCartney never had any grandiose notions of his art. It’s entertainment, and people who want to read more into it generally receive a shrug from him. You should hear his songs, see his movies, and judge their success by how you feel afterward. Of his new film he says, “If people come out of the cinema not cursing me, saying, ‘I didn’t waste my time or my money,’ then that’s fine.”

Paul McCartney’s sweet, fey, melodic love songs have been criticized for their “shallowness,” particularly when the heat was on and the world was busy comparing his to John Lennon’s obscure, anarchic songs (“What does ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ mean?” we all wondered with delight). “All my life people have said, well, that’s sort of sentimental, isn’t it?” he says in that familiar Liverpudlian lilt. “But a heavy, Shakespeare thing? That’s not really who I am. I don’t think ‘light’ is terrible; ‘heavy’ is great. Some Like It Hot was light — but a very great film.” His favorite entertainer of all is Fred Astaire, who is the embodiment of McCartney’s songs: brilliantly talented and light as air. “Sentimental is the bottom line for most people. As for the critics, I just have to let them at this film, like hyenas on the bone.”

Paul’s sentences are sprinkled with animal and plant imagery, and indeed what he seems most realized talking about is his farm at Kintyre, Scotland, where he lives with his wife, Linda, and their four children, Heather, 21, Mary, 14, Stella, 12, and James, six. It’s not technically a working farm, since the animals are neither killed nor eaten. The McCartneys became vegetarians one day when, in the middle of a lam roast, one of their own four legs of lamb wandered into the kitchen. “That was it,” Paul says. “Now we don’t eat anything that has to be killed for us. We’ve been through a lot, coming through the Sixties with all those drugs and friends dropping like flies, and we’ve reached the stage where we really value life.

Some interviewers have been put off by the McCartneys’ animal and pro-life talk, perhaps because it seems a device by which the deflect more personal issues. “We talked to a woman from a French magazine,” Paul says. “She led us on, ‘And you like sheep, don’t you,’” he mocks her patronizing, encouraging tone. “And so we went on and on about our farm and our animals. Then she reported in her magazine, ‘All they bloody talked about was sheep, sheep, sheep.’”

Linda McCartney too talks about her animals, but she speaks with the conviction of someone who has loved them all her life. As a young girl, Linda was so anxious to have her own horse that she lied to her friends in Scarsdale, New York, where she grew up, telling them that she owned one, a very beautiful one. Now she does — an appaloosa stallion — in addition to “millions” of other animals. The RSPCA (Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals) regularly calls Linda with homeless creatures. If they’re not predators, they usually find a home at the McCartneys’.

“Let’s talk about peace,” she’s apt to say, and because I’m thrown when people come out with what sounds like post-hippie flower-child talk, I respond slowly, cautiously, as if she’s said something so general, so broad I can only half sense its meaning. I am suspicious of interviewees’ evasions; she of interviewer’s intrusions. What I soon become sure of, though, is that “peace” is not a way for Linda to avoid other issues. It is a genuine concern that crops up constantly in her conversation and is meant not only in a vague, global sense. She means peace among animals, between a man and woman, between friends. “Why are we so crazy?” she asks, as if of the wind. “Life is so beautiful…”

He wariness of words (“I hate them,” she says) next to Paul’s easy, offhand way with them belies the fact that she seems more open, more emotionally accessible than her charming husband. After 20 years of being interviewed, he has mastered an ostensible warmth and polish she doesn’t have: he is “on” throughout the interview, she wanders in and out. Paul moves away quickly, deftly, wittily from places he doesn’t want to go, while she lights up when a subject moves her, becomes vaguely preoccupied when it doesn’t. She is most comfortable talking about her feelings, even though she doesn’t believe they’re of interest.

“Linda is a nicer person than I am,” Paul says of his wife. “Women are usually nicer,” he adds, “and I have a theory about that: it’s because they’re closer to nature. They get their periods and have babies.” His theory seems to be a new one to him, leading me to believe the whole issue of men and women and their interaction is also probably new — about 15 years old, dating from the time Linda came into his life.

Paul is still not at home with emotional issues, sometimes sounding trite or uninterested when he talks about them. If any emotion subject is likely to elicit a cheerfully dismissive crack from Paul, it is the subject of John Lennon’s death. He is reported to have said to a reporter who stuck a microphone in his face after the shooting, “It’s a drag,” and was thereafter accused of both flippancy and indifference.

The offhand remark, however, is indicative of Paul’s style, not a measure of his feelings, and to this day he gets that raised-eyebrow, defensive expression when Lennon is mentioned. “If he were alive,” I asked him, “would you want another conversation with John?” “I’ll have two, if you don’t mind,” he says, wit at the ready. Then, more seriously, but slightly agitated, “You know, I can’t even really think about it; it’s like a dream. It’s all just too far out for me. The saving grace of it all was that in our final conversation we weren’t arguing about business, which we had done for about ten years. We just talked about our families, we laughed, we smiled.” We leave the subject quickly.

Of all the rock stars and their wives, it is Paul McCartney who is adored. He is the darling of the press, just as he was the darling of the Beatles. Linda McCartney, on the other hand, has been portrayed a the Wicked Witch of the West. “Haven’t I just?” she exclaims when I bring it up. Linda is, as Paul’s song says, lovely: She wears almost no makeup, and in her navy suit and yellow cotton shetland she could be right in preppie Scarsdale, New York. There’s a genuine sweetness about her, a gentleness and shyness that she used to cover by seeming above it all. “I came on a little aloof in the early days, a little blasé, but life was crazy for me and I wasn’t used to it,” she says. “There are certain kinds of people I just seem to rub the wrong way,” she reflects, “and, well, I never did suck up to the press. But I was the total opposite of everything I read about myself: ‘Ooooo, look at the way she wears her hair; look at the way she dresses! She talks back! She’s so fresh!’ And then suddenly those I did care about thought I had become ‘big time.’ I remember a friend of mine, a journalist whim I knew when I was a photographer in New York. I thought of her about a year after I got married and thought I’d send her a Christmas card. She wrote in the paper, ‘Linda McCartney sent me a postcard today because they’re touring America and she wants me to say nice things about her.’”

Then, she adds darkly, “I was blamed for the Beatles breakup. God, I’m not that powerful.” She pauses for a long moment. “I remember saying to Paul, ‘You know, people quite liked me before I married you.’”

Linda married Paul in March, 1969, the same month John Lennon married Yoko Ono — and moved to England with him. The Beatles were already breaking up, and it was, like a complicated divorce of a once-in-love and famous couple, shocking and prolonged and public and painful. “I remember Paul saying, ‘Help me take some of this weight off my back,’” Linda says, “and I said, ‘Weight? what weight? You guys are the princes of the world. You’re the Beatles.’ But in truth Paul was not in great shape; he was drinking a lot, playing a lot and, while surrounded by women and fans, not very happy.” Linda recalls: “We all thought, oh, the Beatles and flower power — but those guys had every parasite and vulture on their backs. I still think I could have eased the pain somewhat more than I did…”

Maybe so, but the pain involved in the breakup of the Beatles seemed to have no end, as one by one they each, bewildered, watched the band dissolve. “If there was one single element that was the most crucial to the breakup of the Beatles,” write Peter Brown and Steven Ganes in their book, The Love You Make: An Insider’s Story of the Beatles, “it was John’s heroin addiction.”

But like most break ups, it’s hard to pin it on any one thing. Certainly John and Yoko were the first to leave the group bodily, and certainly too their various bed-ins and nude album covers didn’t thrill Paul. But the conflicts were deeper than any of us know. The marriages all dissolved in messy, music-business fashion, and even today the complicated problems of Apple, their recording label, remain unsolved. Long after the technical breakup, the Beatles aired their dirty laundry, as it were, in public, which was both sad and a little thrilling to a public that didn’t understand why the animosity had grown so among what it saw as four beloved and brilliantly successful brothers.

In case it wasn’t clear to everyone that the breakups was final and fine by Paul McCartney, it became clear when his first solo album, McCartney, came out. Inside the album was an interview with Paul — by Paul.

Q. Are you planning a new album or single with the Beatles?

A. No.

Q. Do you foresee a time when Lennon and McCartney become an active songwriting partnership again?

A. No.

Q. Do you miss the Beatles?

A. No.

Later, when he came out with his second solo LP, Ram, the cover was a photograph taken by Linda of Paul grabbing a ram by its horns. Inside was a shot of two beetles fornicating; a graphic illustration of how Paul felt he was being treated by his former mates. John Lennon’s next album, Imagine, had a postcard tucked in the album mocking Paul’s Ram cover; John was grabbing a fat pig by the ears. The lyrics of some of the songs were insulting to Paul’s Ramtunes…and so forth…

It was always Paul and John, Paul and John. Nobody compared either one with Ringo Starr or George Harrison, but the two seemingly opposite men were constantly compared and their rivalry encouraged it. As Linda says, “Oh, yes, John was the creative, weird one; Paul the soppy one,” yet, she adds, “They were equally complex — and creative — and so romantic. They were both, in a funny way, the same.”

True, but to the public they couldn’t have seemed more opposite. John was always busy shedding skin after skin after skin, while Paul was busy becoming ever more comfortable in his own. John was fighting, always to leave his lower-middle-class origins, his old ways of thinking, through therapies and drugs and anything he could find; Paul seemed to be clearly getting back to where he once belonged. John seemed always to be announcing a “new” John Lennon; Paul was striving to be happy with himself as he was, a man who loved to fill the world with silly love songs. John was intent on living on the edge, doing the outrageous, handing over his psyche to Yoko for development. Paul seemed to find more creativity in the middle of the road, and what he handed over to Linda was his heart more than his head. At first, Linda was not prepared for her new life as the wife of the star she so admired. After seeing the way things really were, and then being blamed for breaking up the Beatles, she was, to the horror of music fanatics, made a member of his new group, Wings. She was then blamed for pushing her way, with little musical experience and undeniably undeveloped talent, into the band. It is clearly not Linda McCartney’s style to push her way into anything, and even if it were, Paul, a serious musician and consummate businessman, was not about to welcome anyone into any group of his unless he wanted her there.

“Want to be in the group?” he had asked her. “Well,” she says to me with a gleam in her eye, “of course I did: I was a Sixties rock’n’ roller, and I pictured the Shangri-Las or the Dells; we’d show up at clubs and get down and sing schwaddy-doddy-doo. But tell me I’ve really got to learn how to play the piano; that I’ve got to sing in tune — what?? We did have fun at first, but then I had every single critic, every single jealous person on my back, and I realized what Paul had been through all those years.” She was learning firsthand about the forces that had shaped Paul for years. About a life with unlimited access to excess. They reached a point where they could have gone from being superstars to supernovas, burning out in a blinding flash, like so many of their contemporaries.

Instead, they chose a simple life back on earth. “We make a point of being alarmingly normal,” Paul tells me. “I’m a father and to me there’s nothing more important.”

There’s little high-rolling, night-clubbing, big-spending. “I miss pizza and Haagen Dazs coffee ice cream,” Linda says, wistfully, and I tell her I know a celebrity who used to have it flown in wherever she went. “I’ve thought of that,” she admits, “but it’s a bit big time for me.”

Paul says they’re pretty free with the children. “I get strict when I think I have to. We don’t swear around the house — usually it’s me who does, and then I have to go around and apologize to everybody.” Linda feels the children are her closest friends. Paul admits having three girls presents difficulties for a man whose reputation when he was young was that of an avowed skirt chaser. “I know what the boys are after,” he says to me, with the air of any father talking to his daughter, “because I know what I was after. And it wasn’t marriage,” he says with a smile. “It had nothing to do with security. It’s very weird when you were man-the-hunter and you know what visiting boyfriends are after.”

Paul will happily discuss his children as a group, but he will not discuss the individual personalities of each. “They’ve all got good hearts: you can take your troubles to them and they to you. I could talk about them ’til the cows come home, but the kids will read it, and we’re purposely protecting them from being the famous McCartney children. They’d grow up and people would say, ‘Let’s see what happened to little John-John and little Caroline, they’re all grown up now!’ Suddenly they’re personalities and have to deal with the pressures of showbiz without lifting one tiny little finger.”

In the midst of the McCartneys’ “almost perfect middle-class values,” there is what some might think of as a chink in the armor: they love marijuana. They are distinctly unrepentant when caught at various borders with weed in their bags, and the question naturally arises, how does this affect the children? Children always reject the habits and values of their parents: are the McCartney children any different? “I say to them, look, what do I do?” Paul says, innocently shrugging his shoulders. “I don’t want to preach this stuff. I used to drink: I’m from this society where if you drink eight pints a day you’re a man. But I think it’s dumb; I’m not a steelworker in a hot furnace all day and I don’t play rugby. Sorry, kids, but I genuinely feel pot is less harmful for me. And they say, ‘Well, Dad, if that’s what you think, it would be crazy to do the other.’ ‘Well,’ I say, ‘it’s illegal, so I’m going to be told off,’ and I hate that part because I want to be the most upstanding father in the world.”

He goes on. Paul admits to being accused of “always being right” and his pot story does smack rather sweetly of a lecture. “Me and your mum,” he tells the children, “have a slightly better than average knowledge of drugs, having been part of what was once called the drug culture. We know harmful, addictive drugs. We know too many people who have died from drugs. One of the great things about Linda and me is that we’ve sown all our wild oats…” “So what happens,” I ask, “when you and Linda are busted?” “The kids say, ‘Oh, Dad.’”

Paul also stresses the normality of his marriage. “It’s a real marriage: anyone out there who’s really married can sympathize. We love each other, but we’re male and female animals living in the same quarters. She does everything different form how I do it.”

“We’re total opposites,” Linda agrees. “I’m a girl from Scarsdale, New York, and he’s a boy from Liverpool, England, and we’re actually living in the same house, living life, getting up in the morning and making a cup of tea and looking at each other and the kids…and people think, ‘Showbiz, they lived happily ever after.'” “No one as any illusions, really,” I say. “Don’t they?” she counters with a smile.

It has been hard, she admits, but it’s getting better all the time. Earlier in the marriage, the background differences created more obvious problems; for instance, back home she never even had to make her bed and, well, Paul’s mother was a nurse midwife who, Paul says, “was hygenic to the point of craziness. I mean, my class likes to polish. You can’t tell a modern woman she should like to polish.”

But he did just that, much to Linda’s horror. “At first, I thought Paul was so old-fashioned, with this tidiness, and this doing your own laundry and your own ironing.” “Why did you have to?” I ask. “Well, when you read the little storybooks, it was the mother and the father and the kids…it wasn’t ‘and then the cleaning lady came and…’”

“Paul was saying that there’s a lovely pleasure in laundering something and smelling it, or ironing something. He remembers the smell in his house, of his mother, his auntie. And his mother died when he was young. So to have a wife who is intelligent, independent, artistic — but who also fills that role — was important. He thought I was missing something: I thought, come on, I want to be outdoors with my horse.

“It’s all teamwork,” she goes on. “If I were working, believe me, I wouldn’t take this, ‘You’re the wife, this is your role.’ Oh, no, thank you. But he goes to work at nine and comes home at five, so it’s fair, really. It’s all changing, so I can’t say it’s bad any more. Men and women used to be lovers, not fighters,” she says, suddenly bringing in her usual peace motif.

There is no doubt that Linda is Paul’s staunchest supporter. “She’s so pro-me it’s incredible. Unbelievable, really.” I believe it. I believe she is the emotional backbone of the relationship, that the feeling side of Paul is largely generated by her. I tell her this, that I have a hunch the things he talks about –animals, vegetarianism, life, love — are because of her. “Say no more,” she says. To my own embarrassment I add that he’s lucky to have her, and worry that I sound obsequious. “That’s what the kids say,” she says frankly. “He is lucky to have me. Cause when I met him, let me tell you: he was down at the club boozing — for a kid from Liverpool with a lot of roots and family, he certainly had been led away from it. He’s right, I am nicer than he is. I care about the right things, things that need caring about.”

Suddenly we are talking about men who don’t reciprocate, who don’t love back, who don’t understand their wives. Linda is passionate on the subject. “Some men make women feel so guilty: they’re their wives’ worst enemies — and that is death,” she says. “And these women keep saying to themselves, ‘But I’ve got a good heart. I am good.’ Imagine fearing your husband coming home!” She looks as if maybe she once did, long ago, but she quickly says, “I don’t like to talk about my first marriage, because it was crazed, and I started going crazy. All I know is that a woman has to say to a man, ‘I have to love myself one hundred percent, and you have to help me love myself just as I am helping you to love yourself.’”

Paul and Linda have been learning to help each other for years, and it’s taken, says Linda, “staying power and a lot of tears. I’ve got a long way to go; I’m still learning.” Has it taken all this time to know Paul?” “Yes,” she says, “and all this time to know myself.”

The sheer longevity of Paul MCartney’s life in the limelight is astonishing. Buried in his mythic past as a Beatle is the strange fact that by 1981 he had been a Wing as long as he had been a Beatle: time does indeed fly, a cliché just beginning to hit home with Beatles fans. And, in an age when someone on the cover of a magazine can be forgotten within the year, Paul McCartney’s every move still appears in every newspaper in the world.

So the term “survival,” literally and figuratively, is as relevant as the term “success” to Paul McCartney, and sheds some light on the life he has chosen. For the McCartneys, caution, conservatism, capitalism, conservation, and deeply traditional values — “alarming normalcy,” as Paul calls it — are consciously cultivated characteristics. They are the family’s protection against burnout, their ticket to a life even legends have a right to — a life in which, as Linda says, “every living thing is free to be happy.” And, as we should know by now, it takes a whole lot more than fame, money, success, and a cute face to be that.