Timeline

More from year 1976

Interviews from the same media

1967 • From Time Magazine

Jun 09, 1997 • From Time Magazine

Spread the love! If you like what you are seeing, share it on social networks and let others know about The Paul McCartney Project.

Interview

The interview below has been reproduced from this page . This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

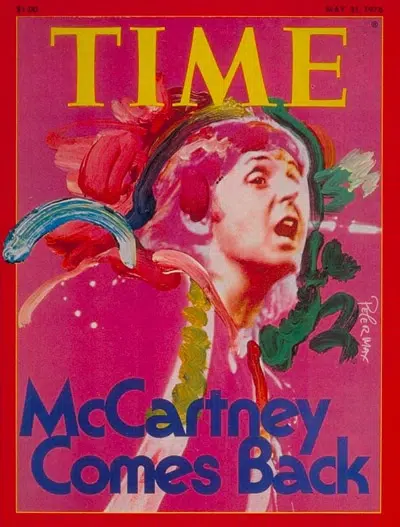

It seems like yesterday’s come round again. Paul McCartney sits alone, stage center, angling slightly forward in a straight-backed chair as he holds his six-string Ovation guitar, playing the first sinuous chords, softly easing into the familiar words.

Yesterday, all my troubles seemed so far away; Now it looks as though they’re here to stay. Oh I believe in yesterday.

The song is a good ten years old. The place goes up for grabs: the collective memory of a generation is galvanized into sweet lyric communion; 16,500 fans in Atlanta’s Omni arena stand, cheer, and start to drift away, remembering.

Or nearly. This is also a brand-new day, and a whole new generation. For a great many members of this crowd—perhaps most —this wonderful, wistful ballad recalls a time they never knew. Beatles are legend. McCartney, 33, is here, right now, in barnstorming triumph, making his first concert tour of the States since he and his three noted mates sang their last song together at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park in the late summer of 1966. McCartney still draws many of the Beatles faithful, to be sure. He has also found a whole new audience, his audience. They have come to hear him, not history.

The concert is a study in controlled flash, spectacular but not gaudy. Even the trappings of the typical rock super-production—smoke bombs, laser beams, meticulous lighting and shifting backdrops—are used sparingly, for maximum effect. McCartney, wide-eyed, boyish, bounces along eagerly on the warm good will of the crowd. He swings into his syncopated little ditty Silly Love Songs, a current hit single (number two on the charts) taken from his latest hit album, Wings at the Speed of Sound, out two months and already gone way past gold (a million dollars’ worth of album sales) into platinum (a million albums sold). His group, Wings, provides him with full-force backing, surprisingly stronger in performance than on records: Lead Guitarist Jimmy McCulloch and Rhythm Guitarist—and sometime vocalist —Denny Laine, co-founder of the Moody Blues, give McCartney a brawny underpinning of sound, while Joe English whacks away at the drums. Paul’s homey wife Linda, 34, is there too, at his insistence. She is hardly a professional musician, but she inflicts no damage either. Linda pokes at keyboards, occasionally chiming in to provide some harmony.

Silly Love Songs is just the sort of tune that comes at the unwary out of car radios and open windows, attaching itself like a particularly stubborn lap cat. It will probably never go away. The brazen breeziness of the music is unshakable.

You ‘d think that people would have had enough of silly love songs,

But I look around me and I see it isn’t so; Some people want to fill the world with silly love songs.

And what’s wrong with that I’d like to know.

It is a sort of refined disco tune, made for dancing and casual listening. At every concert Silly Love Songs gets the same amuck reception as Yesterday or any of the other five Beatles tunes McCartney performs during the course of the evening. Sometimes even bigger. Like much of McCartney’s recent work, the song slips neatly, without fuss, into the mainstream.

This is a course McCartney has been following since John Lennon initiated the breakup of the Beatles in 1969 by telling Paul “I want a divorce.” McCartney’s first few albums, done solo or with Linda or with the constantly metamorphosing Wings, survived uncertain financial prospects and some serious critical drubbing. 1974’s Band on the Run got raves, however, and won the first platinum record McCartney did not have to split four ways. Venus and Mars, released last year, was just as successful, and McCartney’s current concert tour—which will land him in New York this week for two shows at Madison Square Garden —is sold out in each of the 21 cities it will blitz. In Los Angeles and New York, all tickets were snapped up within four hours. Right now, McCartney is bucking Elton John as Pop’s top gun.

McCartney is more than a celebrity, because he is part of the poignant, exalted contemporary myth of the Beatles. Each member of the group had a persona that was clearly defined. George Harrison was the shy mystic, Ringo the innocent good-timer, John the dark poet, Paul—well, the one who would make the best impression on a weekend in the country. His bounteous melodic gifts seemed to be reflected in the brightness of his step, the openness of his smile. His impishness, and his considerable charm, always had an ironic undercurrent of worldliness and assurance. Even now, in performance or in conversation, he has the surprised sophistication of a gremlin who has just been caught under the drawbridge compromising the fairy princess.

It is not for any of this that Paul is popular, however. It is for the music he is making, the flowing Pop that typifies, even defines, the snug place much contemporary rock has found. When Lennon and McCartney wrote “Why don’t we do it in the road?” neither one of them was talking about the middle, which is where Paul finds himself now, bopping straight down the white line. M.O.R.—”middle of the road”—is what the music business calls it, and that is the course Wings most frequently flies. McCartney is tempering the revolution he helped to create.

The Top 40 is where the money is, but never the heavy action. Bob Dylan, a visionary who helped alter the course of contemporary popular culture, is regularly outsold by the whimpy Carpenters, and has had only a handful of singles in the Top 10. One of the most remarkable things about the Beatles was their ability to have it all: to catch and change the spirit of the times, to be wildly popular, vastly influential and still adventurous, to amuse their audiences and make demands on them as well. Rock ‘n’ roll was born in the 1950s, out of black rhythm and blues mostly, and it took it just about a fast, funky decade to reach its adolescence. Dylan and the Beatles were most influential in bringing it along. In the early ’60s it might have seemed heretical to suggest that rock could be a vehicle for intimate self-expression, for anger and confusion, or a cultural revolution. By mid-decade, all that was a foregone conclusion. Rock music had scrounged for and found its own randy legitimacy.

The legitimacy has lasted, but, in 1976, some of the heat has died down. The music itself has become diffuse. Pop is not just rock: it is also disco, soul, reggae, country and ballads. The hottest trend in Top 40 music seems to be themes from successful TV shows. Last week’s charts had no fewer than four, including the title songs from Baretta and Laverne and Shirley. When a smart, articulate song like Paul Simon’s smash 50 Ways to Leave Your Lover gets to the top, it seems like a happy accident.

“The scene is wide open,” says Clive Davis, president of Arista, which shared in 1975’s booming record sales of some $2.3 billion. Danny Goldberg, former vice president of Swan Song Records, which has hit it big with Led Zeppelin, complains that “everybody in the business knows a new era has got to come, but they’re too busy cashing in on the old one to help it along.” Some are helping, either by working their own personal territory (like Randy Newman, Ry Cooder, Tom Waits and James Talley) or, like Simon, Dylan, Bruce Springsteen (TIME cover, Oct. 27) or The Band, trying to make their private property public. There are superb performers (like Linda Ronstadt), and wizardry writers (like Jackson Browne) who are learning the tricks of showmanship. But finding spirited new directions for music is a tradition that, for the time being, is not widely practiced. “Now it has become fashionable not to be too serious,” comments Jon Landau, producer of albums by Springsteen and Browne.

As a Beatle, McCartney ebulliently proved that he could mix with the best of them, but at the moment he is having fun being flippant about rock’s old insistence on relevance. His tunes are elaborately homespun, lined with shifting, driving rhythms and coy harmonics, their lyrics full of flights of gentle, sometimes treacly fantasy. There are little science-fiction ditties and frequent paeans to Linda. Even during his Beatle days, McCartney was something of a sentimentalist, and not embarrassed about it. At this point in his development, he seems pleased to be a first-rate performer and a composer of clever songs. “People say the music’s not as strong as it was,” he told TIME Correspondent James Willwerth. “But quite possibly it is. If you’re not a critic, not some old person who’s been around the music business a long time, maybe it’s as strong. And if you’re a young, vital person who goes to discos looking for birds and all that, maybe it’s just fine.”

This puts McCartney in the company of good music craftsmen like the Eagles and Neil Sedaka, a singer-songwriter of strong commercial rock in the late ’50s. Sedaka lay low during the Beatles era, but in the past few years, with the enthusiastic support of his friend Elton John, has come back as strong as ever. His music, somewhat more urbane, remains essentially unchanged: catchy songs designed for the top of the Pops. Sedaka treats McCartney as a fellow tunesmith of the highest order. “A Pop hit has to have certain hooks you can hang your hat on,” Sedaka points out. “The hooks can be either musical or lyrical, but the best is a marriage of both words and music. McCartney does this. A song like Listen to What the Man Said is terrific.”

Listen to What the Man Said is a good tune, all right, with shrewdly alternated rhythms and a lyric that goes down easy.

. . . love is fine for all we know.

For all we know our love will grow—

That’s what the man said.

So won ‘t you listen to what the man said?

Still, at his best McCartney writes words and music with the sort of unruffled brilliance and canny razzle-dazzle that can put both Sedaka and songs like Listen to What the Man Said straight in the shade. Take this example from Band on the Run:

Well the rain exploded with a mighty crash

As we fell into the sun,

And the first one said to the second one there

I hope you’re having fun.

Even the brightest of his recent songs, however, carry their quality very lightly. “True, Paul’s not innovative at the moment, but nobody is except Stevie Wonder,” says Singer-Composer Harry Nilsson, a Beatles crony from way back, adding with some heat, “I don’t buy all that crap about saccharine lyrics.” Says Bhasker Menon, 41, president of Capitol, which distributes the McCartney records in the U.S.: “Paul is a consummate musician. When he does Yesterday it is one of the most beautiful songs I ever hear.” Perhaps meaning to flatter, he adds with impolitic directness, “As a songwriter I would compare Paul to John Denver.”

McCartney’s roughest critic over the years was also his best friend. “He sounds like Engelbert Humperdink,” said John Lennon of McCartney’s first solo efforts. Later, in Lennon’s remarkable album Imagine, he put it directly to Paul in How Do You Sleep?, a fierce song full of anger and injury:

A pretty face may last a year or two;

But pretty soon they’ll see what you can do.

The sound you make is Muzak to my ears.

You must have learned something in all those years.

The song was less spiteful than revealing, fueled with the kind of fury that can come only out of friendship, injured perhaps irreparably, that refuses either to disintegrate completely or to mend. Wounds went deep, and they stayed open for a while. “I find that I have to leave all that behind,” McCartney says now. “It’s a decision you make, that’s all. Otherwise I would have ended up thinking John was the most evil person on this earth . . . saying all that.”

The reasons for the bitter dissolution of the Beatles, and the protracted legal brawling that followed, are all a matter of public record, if not common knowledge. Once they stopped touring in 1966, the Beatles began to grow in different directions. Their varying attitudes toward business affairs were as typical of these changes as the songs they wrote or the women they chose.

The Beatles did not own the rights to any of their songs. Their two major sources of income—record royalties and music publishing—were almost totally controlled by others. Without the friendship and advice of their manager, Brian Epstein, who died in 1966, the Beatles found themselves in a series of disastrous business deals. They lost their publishing company in a stock-exchange fight, then plunged into a series of financial misadventures through their management company, Apple Corps Ltd.

The group had started its own recording and production company, Apple Records, which was also meant to serve as a kind of Ford Foundation for the counterculture. The place attracted all sorts of daytrippers, rip-off artists and weirdos. “People were robbing us and living off us,” Lennon comments. “Eighteen or 20 thousand pounds a week was rolling out of Apple and nobody was doing anything about it.”

Not for want of trying. McCartney had met Linda Eastman in London in 1967. A year later he was living with her in London, and he looked to her father and brother, Lee and John, fashionable, tough-minded New York show-business lawyers, for advice on Apple’s chaotic affairs. Lennon, in the meantime, had met up with Allen Klein, a free-swinging wheeler-dealer who once sent out Christmas cards with this greeting: “Yea though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, because I’m the biggest bastard in the valley.”

Klein and the Eastmans did not get along. “It was a choice,” John recalled recently, “between the in-laws and the outlaws.” John, George and Ringo went with Klein; McCartney, now married, stuck close to his new family. To extricate himself Paul would have to sue not only Klein but the rest of the Beatles, and in 1971 he did. “It all came down to that—I had to fight my own pals,” McCartney recalls. “Of course, by that time, they didn’t look like such pals. I was having dreams, amazing dreams about Klein, running around after me with some hypodermic needle, like a crazy dentist.”

Doubts, recriminations, bitterness. “You rarely get artists who are good businessmen as well,” comments James Taylor, whose first album was issued by Apple and lost in the prevailing madness. “The Beatles were artists.” It is not over yet. Klein is still suing Apple Corps Ltd. for all manner of unclaimed commissions. This legal furor to date has cost the Beatles £ 7 million in royalties.

The emotional cost is not so easily calculated. Lennon and McCartney both retreated, Paul seeking the shelter of quiet, closely restricted family life while John exorcised all his demons in public. Apart, they reveled in the sort of vocational excesses they had once checked in each other. Lennon collaborated with his wife, Yoko Ono, on a series of noisome avant-garde records, then switched to abrasive social protest on subjects as various as the Attica killings and the oppression of women. McCartney wrote about the undemanding pleasures of farm life and domestic bliss, going so far as to record a version of Mary Had a Little Lamb four years ago.

“Looking at it purely bluntly,” McCartney reflects now, choosing the words carefully, “there was sort of a dip for me and my writing. There were a couple of years when I had sort of an illness. I was a little dry. Now I’m not ill any more. I feel I’m doin’ fine.” Shoring up his defenses, drawing his family tight around him, McCartney hymned Linda endlessly. “You want to know about his family life, you can hear it in his music,” says McCartney’s brother, Mike McGear, himself a Pop singer. Those qualities that many critics find cloying could also be melodic acts of self-persuasion. The songs may not work for the same reason that many of Lennon’s from this period do not: they are written and sung more out of need than conviction.

Whatever the reasons, this period is mostly past, and McCartney has embraced the good life with a fine passion. “Paul’s very worried about losing his fans because of being too Establishment,” John Eastman observes, but McCartney has no hesitation in announcing: “It’s nice waking up in the morning now. Instead of the dregs of the night, you have the refreshing faces of children and a cup of tea.” There are three faces likely to pop up in front of him—Heather, 13, Linda’s daughter from a previous marriage, Mary, 6, and Stella, 4—and a nice assortment of houses for the daily awakening.

Despite all the money he has lost, Paul is now worth £ 10 million. The McCartneys have adopted a pastoral variation on rock’s royal style. They keep a home in London’s tony St. John’s Wood, but, says a member of the McCartney staff, “it is definitely not a show house.”

The family also spends a great deal of time at a farm in the Scottish Highlands, a retreat that has the advantages of rugged beauty and almost total inaccessibility. To reach the unprepossessing stone farmhouse, a visitor must start down a tiny, unmarked country lane that leads to two footpaths, each passing through separate farms and yards. Impressively large and vocal dogs patrol the neighbors’ property. If an intrepid fan tried the back way, he would be stopped by an impenetrable bog.

If anyone managed to surmount these natural obstacles, there would be little enough to spy on. Mum might be cooking up a batch of her special pea soup (secret ingredient: sea salt), Dad might be settled back with some favorite reading material—science-fiction novels and comics, mostly. The whole family could be gathered around the table, enjoying a favorite meal of eggs and chips and larking about, hitting Dad for “requests”—everything from That Doggy in the Window to songs composed on the spot, to order, for whatever child does the asking. Dad may be working on the score for a cartoon movie about a bear named Rupert who flies around in little glass balls, or sawing away on the kitchen table he is building for Mum (“I’m not very good at building—I wonder if it will stand up”). If the skies are fair, he may be in the fields, helping with the shearing. He loves to fall back on a pile of just-shorn wool, burrow down in it, enjoy the aroma, turn his face up and feel the tang of the air, the strength of the sun.

McCartney is proud to be a little bit of old England—even though the homeland taxes him up to 83% on earned income, up to 98% on investments. “I love the place,” he says. “I see it as having one of the biggest potentials in the world.” The McCartney politics are conservative. “Paul would be a sort of Republican,” says John Eastman. His philosophy of child rearing is elemental. “We try to be very open with them, but not to the point of Dr. Spock, where they sort of run us.”

Smarmy as all this may sound to any fan used to high-voltage tales about the profligate life of rock stars, McCartney draws enough sustenance from his rigorously imposed family structure to have it re-created for the current Wings tour. Houses and an apartment are rented in four cities—New York, Dallas, Chicago and Los Angeles. The McCartneys, the boys in the band and assorted advisers and technicians then fly to each gig in a private plane. There is a nanny in attendance, and a “smoothie girl,” who packs her blender, fruits and assorted organic goodies and can whip up a quick-energy smoothie drink. A special advance man, Orrin Bartlett, formerly of the FBI, scouts out each concert venue and makes inquiries about bomb threats and grudge calls. Paul worries about snipers.

It is Linda, however, who catches most of the flack. When she first hooked up with Paul, she had been on the rock scene, snapping photos, for a few years, and had been involved in affairs with prominent musicians. Born in Scarsdale, raised to wealth, Linda was considered by many just a high-flown groupie. But according to Journalist Robin Richman, she had “a sense of breeding and culture that all these guys responded to. Linda’s place in Manhattan was like home for some rock stars, a place they could crash if they didn’t feel like a hotel.”

Attacks—similar to the ones on Yoko Ono—reached a fever pitch when Linda began chipping in on the music. According to her husband, it was all his idea. He started her at the keyboard by pointing out middle C. “I could have done a smart bit of p.r. during the time she was being criticized,” Paul told Beatles Biographer Hunter Davies. “But I thought, ‘Sod ’em.’ I don’t have to explain her away. She’s my wife and I want her to play with the group. She’ll improve. She’s an innocent talent. That’s all rock ‘n’ roll music is. Innocent music.”

Unlike most rock superstars, the McCartneys try to stay in touch with reality. A couple of years ago, after Paul complained about not meeting people on a personal level, Wings toured rural England for a month, stopping each night to play at friendly-looking pubs. The isolated feeling popped up again a few months after a concert in Berlin. This time the solution was quicker and zanier. Paul and Linda painted the lyrics of Silly Love Songs on a bed sheet and paraded it along the Berlin Wall. The trek ended at Checkpoint Charlie.

Like the rest of rock’s nobility, the McCartneys can indulge any generous or acquisitive whim. Linda has sponsored a couple of struggling artists. On the current tour, the family got off a Texas freeway at the wrong exit, spotted an Appaloosa grazing in his pasture and bought the animal there and then.

Any tour brings unwelcome questions about a Beatles reunion. Paul and John—”They talk a lot now,” says a friend of Lennon’s. “All the guys do”—got together with their wives recently in New York and discussed not reunion, but how to field questions about it. “You’re really going to get all that,” Lennon reminded McCartney. The requisite denials come from the McCartneys with weary certitude whenever a journalist raises the subject.

The persistent interest is understandable, however, based not only on nostalgia but also on a sense of what is happening once again with Beatles records. Even as McCartney brings the crowds to their feet at his concerts, five old Beatles songs are in the British Top 20. Capitol is gearing up to release an upbeat anthology of Beatles goldies in two weeks, and plans to spend a million dollars on promotion alone, the largest campaign in the company’s history. Along with TV ads, Capitol plans to bedeck the country’s leading record stores with Beatles banners and posters and, accordingly, has purchased 110 miles of clothesline.

It does not seem sufficient to hang such a big dream on. Lawyers for the four Beatles had uncommonly long, closed meetings most of last week in Los Angeles, and were adamant about discussing none of the details. A West Coast promoter and part-time Barnum named Bill Sargent has offered the group $50 million for a reunion. Said Paul: “The only way the Beatles would come together is if we wanted to do something musically.” The others say nothing. It has been this way since the group disbanded, brush fires of hope fanned a little, then stamped out.

A reunion would be particularly wrenching for McCartney just as he is enjoying his first full success since the breakup. It might not be easier for anyone else either. Jenny Brandt, a 17-year-old McCartney fan, said it best as she waited to get into the Philadelphia concert. “Wings is doing good on its own, even though it’ll never be the same as the Beatles. But I don’t want them to get back together. It would be a super-let down. They could never produce the music they once did. It’s a different era, and they’ve changed in different ways.”

Some years back, of course, Paul McCartney put it well, too: let it be.

Contribute!

Have you spotted an error on the page? Do you want to suggest new content? Or do you simply want to leave a comment ? Please use the form below!