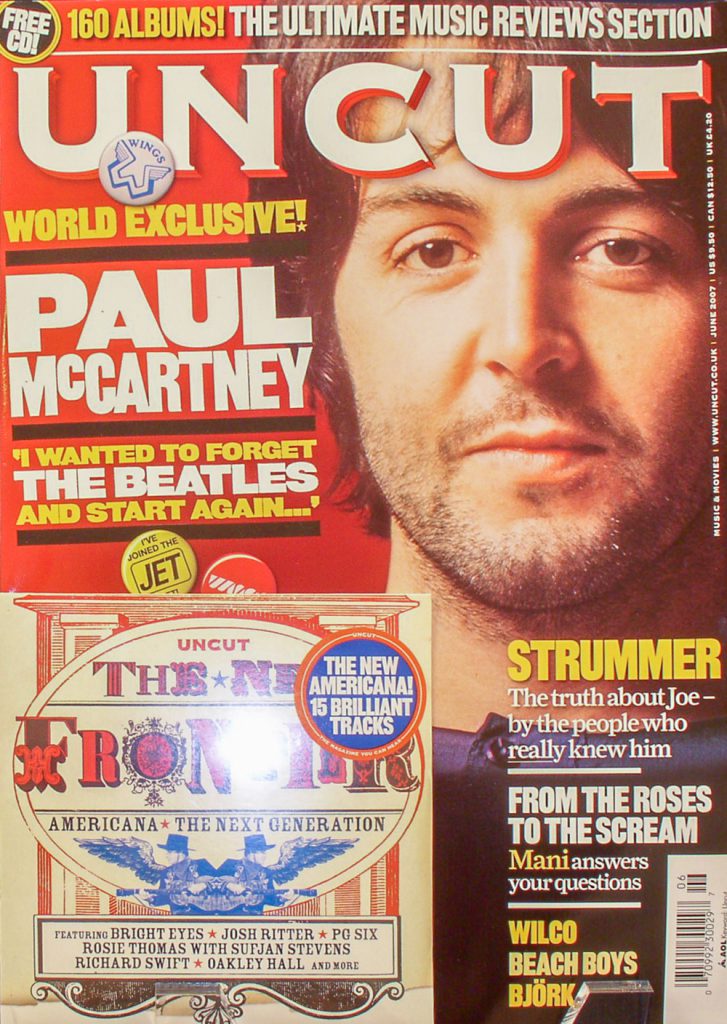

Interview for Uncut • June 2007

Paul McCartney: I wanted to forget The Beatles and start again

Interview of Paul McCartneyInterview

I bought a mandolin. It isn’t tuned like a guitar, so I didn’t know my way around it. But the feeling of picking my way through and finding chords was magic. It was like I was 17 again. I remembered – this is what its all about. It was like me and John (Lennon) learning piano. You play, and then you hit a wrong note, and you go (in amazement, delight) ‘Oooh’ And you write a whole song on that chord. The excitement of getting the mandolin, finding new chords – that’s really lifted me, that has. That’s the opening track on to my new album.

March 15, 2007. Soho Square is bathed in buoyant sunshine as a few lunchtime stragglers drain their lattes and wander back to work. Between azure sky and coffee aroma, the only affront to the senses comes from workmen entrenched behind fencing, cacophonously digging up the road. “Replacing London’s Victorian Water Mains”, read the signs around the square.

Sir Paul McCartney emerges from his second-floor office overlooking the road works and steps into a cluttered reception area. He’s wearing a white shirt and grey trousers with pin-sharp creases. His hair is a discreet older gentleman’s brown – his stylist would know the exact shade – and his manner is quizzical. He squints at his young publicist, pretending not to recognise him. Then he turns to me, gesturing towards his office with a thumb. “Are you comin’ in here, then?”

Bright and airy, the office contains an executive desk on one side, and some chairs and a chaise longue on the other. There’s a table where an interviewer from Uncut can rest his coffee-mug and tape recorder. A piece of abstract expressionism by Willem de Kooning adorns the far wall. In a corner stands a beautifully preserved Wurlitzer jukebox, all sleek contours and strawberry-pineapple fluorescence. The workmen’s drilling intrudes through an open window. McCartney presses a button and Presley’s “Hound Dog” drowns it out.

At this moment, his estranged wife, Heather Mills, is somewhere across London, engaged in a hectic itinerary of TV and radio appearances that will dominate tomorrow’s newspapers. Teams of highly trained showbiz correspondents will dissect her cryptic claims regarding the McCartney divorce. (“There are huge powers. I don’t have that powerful system he has. There is a huge agenda about trying to destroy me.”) As if oblivious to her activities, McCartney seems presidentially calm this afternoon. But not even presidents can stop the passing of time. He’ll be 65 on June 18. You’re struck by the facial gauntness and the husky cracks in his voice.

We’re here to talk about Wings, the band he led from ignominy to record-breaking glory in the 1970s with his intrepid but musically L-plated wife Linda. However, he also slips in a mention of an imminent new album, his follow-up to the well-received Chaos And Creation In The Backyard (2005).

“I bought a mandolin,” he explains. “It isn’t tuned like a guitar, so I didn’t know my way around it. But the feeling of picking my way through, and finding chords, was magic. It was like I was 17 again. I remembered – this is what it’s all about. It was like me and John [Lennon] learning piano. You play, and then you hit a wrong note, and you go [in amazement, delight] ‘Ooohh!’ And you write a whole song on that chord. The excitement of getting the mandolin, finding new chords – that’s really lifted me, that has. That’s the opening track to my new album.”

Great. Can you tell me the title?

“I don’t think so, actually,” he hesitates. “I’m never sure with that… I want to tell you the title, definitely, but…”

Days later it’s announced that the album signals the end of McCartney’s 45-year association with EMI, and will instead be sold in 13,500 Starbucks stores as part of a revolutionary deal signed with the planet’s foremost coffee retailer. “It’s a new world now, and people are thinking of new ways to reach the people,” McCartney’s statement runs. One commentator estimates the album could reach 44 million customers a week. Not bad for a mandolin player with only limited experience.

Wings: the very name carries a pejorative echo in the universal mind. Wings: that FM radio colossus. A precarious rope-ladder from Abbey Road to “Ebony And Ivory”. Wings: a song about a peninsula that stayed at No 1 for a million years. But the Wings story epitomised McCartney in action – his bloody-mindedness, his inner battles between cliché and genius, his loyalty to Linda Mac, his irrepressible gung-ho spirit. And he needed every ounce of that. Wings: the poor saps with the impossible job of following The Beatles.

“I knew it was impossible,” says McCartney straight away. He holds up his hands. “Come on. It’s the impossibility of the universe to follow The Beatles, as all bands ever since have found. Even bands who have almost been successful at it.”

But if Wings are Wings, McCartney is McCartney, a pan-global superstar and billionaire who doesn’t strictly enjoy having his judgment questioned. There’s a physical emphasis to him in person that doesn’t come over on TV, and certain remarks have an unmistakable edge. He dismisses the rock critics (“They come and go”) who sneered at every Wings album except Band On The Run. There are no olive branches for Beatles fans who found Wings maddeningly inconsistent (“That’s too bad, isn’t it? It’s my life”). To McCartney, Wings always made perfect sense.

“It’s like with ‘Mary Had A Little Lamb’,” he scoffs, referring to a much-maligned 1972 single. “People said, ‘Oh, he only put that record out because [“Give Ireland Back To The Irish”] was banned.’ It wasn’t like that. I had a baby. We used to sing the song around the house and I thought it sounded catchy. I probably should have thought, ‘Yes, but is this the record that you want in your portfolio right now? Is it “the move”?’ But I don’t think in terms of ‘moves’.”

Wings were born out of a farmhouse, a marriage, “almost a nervous breakdown” and a pair of sketchy, convalescent solo albums. In 1969 McCartney had grown weary of driving from his St John’s Wood house to Savile Row every day to have the same circular argument with The Beatles about whether the notorious Allen Klein should be their manager, and what percentage of their income he should get. “The others were saying, ‘He’s great.’ And I was saying, ‘No, he isn’t! He’s not great at all, and 20 per cent is too much for someone to take off The Beatles. This is not The Bottles. It’s The Beatles, and it’s a fucking great group, and someone should take 10 per cent, if that.’”

Exhausted and defeated, McCartney withdrew from London for a simpler life – with his American wife Linda and their daughters – at his farmhouse in Argyllshire, near the Mull of Kintyre.

“It was hippie times,” he smiles, “and Linda and I were looking after ourselves, planting vegetables, farming. I was mowing the fields, shearing the sheep and stuff. It was an attempt to return to basics. I felt like I needed to get back to ‘me’. I’d got way too far away from who I was.”

By mid-1970, with McCartney vilified nationally as The Beatles’ executioner, Linda was nursing him through a year-long depression on the farm. She was both rock and collaborator. Having sung a harmony on “Let It Be” (uncredited), she now added her folksy voice to some of Paul’s best early solo work (“Another Day”, “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey”), as well as some of his worst. His commercial stock remained high – McCartney topped album charts in America, Ram in Britain – but neither critics nor old friends had kind words for the homespun, hit-or-miss ditties he now favoured. “I don’t think there’s one tune on Ram,” lamented Ringo Starr in 1971.

In bed one night, Paul asked Linda a question. Did she fancy being in a band? “She said, ‘Ooh I don’t know, really,’” he recalls, adopting a Mavis Riley quaver. “I said to her, ‘You have to imagine there’s a curtain there, and we’re behind it, and if it opens up… would you like that? We’d be the band and there’d be an audience out there. Could you get into that?’ She said, ‘Yeah… I think so.’ We took it as lightly as that. Mick Jagger said [scornfully] ‘Why did he get his old lady in the band?’ I wanted to be with her, that’s all.”

On November 8, 1971, the McCartneys launched their new band, Wings, at the Empire Ballroom, Leicester Square. Completing the quartet’s line-up were New York drummer Denny Seiwell and ex-Moody Blues singer/guitarist Denny Laine. The Empire, with its roots in Victorian music hall and Lumière Brothers moving pictures, provided a suitably historic setting for Wings’ inauguration.

But when their first album, Wild Life, appeared in December, it was patently substandard. Denny Seiwell tells Uncut that five of the eight songs were first takes. The rock papers savaged it. “This is not even acceptable pop music,” wrote one reviewer. McCartney was undaunted. Wings were going on the road.

Britain was hit by a power crisis in February 1972. Affecting heat, lighting and amplification, it caused numerous gigs to be cancelled, and there were fears for musicians’ livelihoods if the situation worsened. In this context, Wings debuted on February 9. They had a new member, Henry McCullough (lead guitar), but no manager or booking agent. They travelled in two vans –musicians, wives, children, dogs, roadies. On the M1, seeing signs for Nottingham, McCullough suggested they try Nottingham University.

“How do you ‘do a band’ was the question,” explains McCartney on the subject of Wings’ low-key, morale-boosting University Tour. “You could do the supergroup thing like Jimmy Page and Eric Clapton. Or you could return to your roots – and that’s what I was doing. I wanted to get away from being huge in The Beatles, and experience being at the bottom again. It was like leaving a very posh job and going to work on the streets.”

The scenario went like this. Wings pull into a uni campus. Their roadies ask the students’ union if they’d like a band to play. “No thanks.” “It’s Paul McCartney.” “Whaat?” Student comes out to the van, sees McCartney, grins in disbelief. It is agreed Wings will play for 50p on-the-door, tonight or tomorrow, whichever is convenient, mate. Wings look for somewhere to spend the night.

“We didn’t stay in many hotels,” Henry McCullough laughs. “It was mostly Mrs Murphy’s bed-and-breakfast. But it was fantastic, like a little English magical mystery tour. Only a man like McCartney could have done it.”

“We were having a great laugh,” McCartney enthuses. “This is what I thought it was going to be about. Camaraderie. A baptism of fire. Learning to play together, getting a chemistry. We only had a few numbers. We had to repeat some of them, pretending they were requests.”

Wings released their first single, “Give Ireland Back To The Irish”, that month. A horrified McCartney’s response to Bloody Sunday (January 30), when 13 civil rights protestors in Derry were shot dead by British soldiers, the song proved bitterly controversial. EMI reluctantly sanctioned its release, but as Northern Ireland teetered on the brink, the single was given no exposure whatsoever. Radio 1’s chart show wouldn’t even mention its title. McCartney was unrepentant. “My family comes from Ireland,” he reasons today. “Half of Liverpool comes from Ireland. That was the shocking thing. We were fighting us. And we’d killed them, very visibly, on the news.”

Wings lay low. The University Tour had created an ‘issue’ in the band, one that successive line-ups would all have to face. Linda McCartney was a novice-standard prodder of a keyboard, and tended to sing waywardly onstage. As everyone from band-members to road crew gritted their teeth, the stoical Linda became the butt of countless jokes during Wings’ lifetime. Henry McCullough remembers losing his temper and telling McCartney to hire a proper piano player. He was told to sit down and shut up.

That summer, with child-friendly single “Mary Had A Little Lamb” gambolling around the Top 30, Wings upgraded from a van to a bus, and toured Europe. Denny Seiwell: “It was an open-top London double-decker bus. They’d painted it bright colours and fitted it with mattresses on the top deck for sunbathing. It only went 35mph, that was the problem. In Germany we were late and they sent five BMWs to meet us on the motorway.”

Incredibly, Wings’ third single, “Hi Hi Hi”, received another Radio 1 ban – this time for sexual innuendo. However, an incident on the European tour would have much more serious repercussions than any BBC embargo. In Gothenburg, Sweden, the McCartneys and Seiwell were arrested and fined for possessing marijuana. Media reports of the bust triggered a second bust at the McCartneys’ farm by Scottish police. Paul now found he was repeatedly denied a US visa. The drug convictions also kept him out of Japan, one of rock’s most lucrative markets.

Seiwell: “That wasn’t just a menial fine that was paid in Gothenburg. That cost him a lot of money.”

Paul and Linda McCartney are sauntering down a dark, unlit road one evening in September 1973, tape recorders and cameras in hand, the red Lagos mud underfoot. Paul, who has chosen Nigeria from a list of EMI’s studios round the world, has multiple duties on his plate – including playing lead guitar and drums on the new album. McCullough and Seiwell, unhappy that their retainers did not increase in line with recent chart success (“My Love”, “Live And Let Die”), have quit – Seiwell by telephone, hours before the Lagos flight –reducing Wings to an overstretched trio. A car passes the McCartneys on the road, and stops. An African man gets out. Paul tells Linda he thinks they’re being offered a lift.

In his Soho Square office 34 years later, McCartney’s face creases up. He is relishing this story. It has already become the interview’s centrepiece anecdote. “They told us at the studio not to go walking late at night, because there was crime and stuff. We just went (sarcastically) ‘Yeah, sure!’ We were hippies. We thought we were immortal.”

The McCartneys have now caught up with the car. Paul gives the man a friendly nod.

“I said, ‘You know what, this is so nice of you – but it’s a beautiful evening and we don’t want a lift.’ I’m bundling him back into the car. ‘Come on, now. Get in the car. Get back in that bloody car.’ I’m doing the Liverpool thing. ‘You’re not giving us a lift. Go on, mate, off you go!’”

He decides to illustrate what he means. Getting up from his chaise longue, he grabs me by the shoulders and tries to push me off my chair. He’s quite a lot stronger than you think.

“So then the car stopped again. Only this time it stopped a bit more sharply – and suddenly all the doors flew open, bam bam bam, and five or six of them jumped out. The little one had a knife. Now the penny drops, finally.”

The McCartneys were stripped of their pricey cameras and tape recorders, and returned to their rented house deeply shaken. Next day, recounting the story at the studio, they were told they would probably have been killed if they’d been a black couple. The robbers had left them alive as they wouldn’t expect white people to identify them.

“Looking back on it, it was funny,” McCartney says, shaking his head helplessly. “I’ve got this – I think it’s basically stupidity. I must admit there’s an element of stupidity there. When I look at these things afterwards, I think, ‘What are you on?’ But I see it as a sort of enthusiastic innocence. It’s enthusiasm to me. Yeah, let’s do this. Don’t worry about that. Everything’ll be great!”

Following the mugging, Wings’ Nigerian adventure turned thoroughly sour. Local musicians came to the studio to intimidate them. Paul suffered a bronchial condition that made him fear he was having a heart attack. Yet the driven McCartney slaved over Band On The Run in Nigeria and London like no Wings project before, and the result was a career landmark. The songs were saturated in infectious hooks. The arrangements were witty and inspired. Band On The Run followed its patchy predecessor, Red Rose Speedway, to No 1 in America, and became Britain’s best-selling album of 1974. The unqualified triumph did wonders for McCartney’s self-confidence. He was back. He’d made a classic. Even John Lennon said so.

And as McCartney now overtook Lennon to become the most successful and critically acclaimed ex-Beatle (ironically the two men had a rapprochement in New York at this time), the image of Wings changed totally. Once a good-time band for blokes and birds, they increasingly catered for a more exclusive, high-end clientele. Dustin Hoffman hung out with them. The Magnificent Seven’s James Coburn was among the startled celebrities on the amusing sleeve of Band On The Run. Wings joined the jet set. By 1976, once McCartney had finally been granted a US visa, there would be $80,000 end-of-tour parties in Hollywood mansions, attended by A-listers Warren Beatty and Tony Curtis. Wings, the band that had played Little Richard covers for 50p on-the-door at Nottingham University, were now grossing $5 million for seven weeks’ work.

The mid-’70s were Wings’ commercial heyday. The albums Venus And Mars (1975) and Wings At The Speed Of Sound (1976), while sorely flawed, dovetailed consummately with the baby boomers’ insatiable appetite for easy-going arena-rock (Eagles, Peter Frampton, Steve Miller) both at home and abroad. Back to full strength after the addition of Jimmy McCulloch (guitar) and Joe English (drums), Wings racked up a fifth consecutive US No 1 album in 1977 (with the triple-live Wings Over America), having obliterated the indoor world audience record (67,100) in Seattle on the tour in question.

Of course, by late 1977 in Britain, there were new forces to compete with. McCartney, never so foolish as to try to identify publicly with the punk scene, instead trusted his judgment and released a misty-eyed waltz, composed in tribute to the area of Scotland where he lived. While the Sex Pistols sneered at stupid old EMI on an album released that month, McCartney and his record company savoured their colossal international hit. Statistically outrageous, “Mull Of Kintyre” sold over two million in Britain alone.

“We were expecting it to be a flop,” McCartney protests. “We thought we should really be putting out something thrashy, fast and loud. But it had occurred to me that there weren’t any new Scottish songs. I like the pipes, you know. The skin-tingling, bloodcurdling thing. So we released it, thinking ‘Nah… it’s not the time for it.’ But I remember ringing here [his office] and the guy said, ‘It’s selling 30,000 a day.’ As a joke I said, ‘Don’t get back to me until it’s selling 100,000 a day.’ And the next week, it was.”

He laughs, and goes on to tell a story – which may or may not be true – about him and Linda being stuck in traffic in the West End when “Mull Of Kintyre” was enjoying one of its nine weeks at No 1. Through the car window, they espied a large gang of punks loitering on the pavement.

“They looked pretty menacing,” he says, rolling his shoulders like Del-Boy in Only Fools And Horses, “and there were a lot of them. I said to Linda, ‘Keep your head down. Get the sunshields [in the car] down..’ And of course one of them recognises me. [Cockney accent] ‘Oi, Paul! Awright, Paul!’ I thought, oh no… The guy’s going like this [signalling for Macca to wind down the window]. So I put the window down a little bit. And he says: ‘You know that “Mull Of Kintyre”? It’s faaking great!’ I thought, ‘Now that is cool. Punks like it.’”

With its buttery production and soft-rock electric pianos, Wings’ 1978 LP, London Town, doubtless kept those punks thrilled. It had partly been recorded on a yacht moored in the Virgin Islands, where Wings relaxed with cordon bleu dinners and water-skiing sessions. So it was a surprise when McCartney unveiled a new Wings line-up that year, featuring two newcomers who looked like members of Blondie. Producer Chris Thomas, fresh from Never Mind The Bollocks, was brought in, and McCartney promised a “raw” Wings sound.

Guitarist Laurence Juber remembers the band listening to “a lot of reggae, new wave, whatever was in the air”. Things looked promising. But Back To The Egg (1979) saw McCartney’s innate conservatism scupper the experiment. He just couldn’t help inviting some decidedly pre-punk acquaintances – Dave Gilmour, Pete Townshend, John Bonham, Ronnie Lane – to participate in an Abbey Road supergroup (the Rockestra) on a couple of gratuitous blowouts.

Stung by the album’s rejection – it yielded no UK hits – McCartney focused his mind on the upcoming world tour. After the UK, Wings’ next stop was Japan, where the authorities had finally relented and allowed McCartney permission to play 11 sell-out concerts. He and Linda flew into Tokyo’s Narita Airport on January 16, 1980. Just prior, Wings had dispensed with their usual sound equipment team, sending their production schedules awry. “The crazy thing is that I hadn’t allowed enough time to rehearse,” McCartney says. “Normally I’m very good about that. But we were only going to have a week to put the whole Tokyo show together. We were up against it. It was like fate…. closing us down.”

The McCartneys approached airport customs: surely a formality. Television crews and hundreds of fans crowded around to welcome them. But McCartney had forgotten – or perhaps was unaware – that 229g (about half a pound) of top-quality marijuana was packed in his luggage.

He leans forward. “I’ve asked myself, ‘Why was that pot in the suitcase? So… obviously. And so much of it.’ I mean, there was not one hint of discretion. And if you see the film of the arrest, the guy is embarrassed to find it. He almost puts it back and closes the suitcase.”

Juber: “I was standing next to him. I looked at the suitcase. Then I looked at Paul’s face. He’d turned white.”

McCartney was escorted to the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Office, where he spent 10 days in a cell, subsisting on bread and coffee. He was denied a guitar. Meanwhile, his lawyers tried legal and diplomatic routes to free him.

“It was such a different world,” he says softly. “It was like going to another planet. They would say, highly curious, ‘You are MBE?’ And I’d say ‘Yeah’, hoping that would carry weight. And it sort of did. They were a bit deferential. Then they said, even more curious, ‘You live at Queen’s Palace?’ I said, ‘Well, no, not actually… Well, yes, quite near.’ I was hoping they might let me off if I lived near the Queen’s house. ‘You smoke marijuana?’ ‘Hardly ever.’ They said, ‘Make you hear music better?’ I thought, God, I wonder if that’s a trap.” After some concern that he might go to prison, McCartney received a fine and was made to contribute £184,000 to the ticket refunds for the cancelled tour. He was then deported.

Everyone in the Wings camp was furious with him for sabotaging a potentially lucrative tour, not least Denny Laine. The faithful Laine had been an ever-present since ’71, on a system of retainers and salaries, and had co-written “Mull Of Kintyre” with McCartney. Later, suffering financial hardship, Laine sold McCartney his publishing rights to the song. In 1986 he was declared bankrupt. He now lives in either LA or Las Vegas – it’s not clear from his MySpace page – and does not respond to Uncut’s email requesting an interview.

Wings officially ended in April 1981 when Laine left. By then, McCartney had released the solo LP, McCartney II (hit single: “Coming Up”) and was wondering if the grass in the suitcase at Narita Airport had been subconsciously placed there by himself – as a non-negotiable, unequivocal way of freeing him from the pressure of a 1980 world tour.

“I wondered. I wonder to this day if there was something strange like that. But it would be subconsciously, because I absolutely wasn’t doing it on the surface. It [his post-Wings solo career] was a new start, an enforced new start. [Pause] Or was it? Did I subconsciously force it on myself? I don’t know. I don’t know. It was a strange period.”

Our interview is over. It’s time for me to leave the presidential bubble. McCartney is still ruminating on spooky, subconscious matters as he shows me to the door. He says he recognises me now. I tell him he’s mistaken, we’ve never met. But he’s adamant: we’ve met before. I assure him we haven’t.

“Is that right? Oh. Well, that’s the wonderful thing about senility,” he beams, accompanying me out into reception. “You’re always meeting interesting new people.”

Last updated on July 29, 2021