Friday, April 16, 1971

Interview for Life Magazine

The ex-Beatle tells his story

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Last updated on October 15, 2023

Friday, April 16, 1971

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Last updated on October 15, 2023

Previous interview December 1970 • Paul McCartney interview for BBC Radio One

Session Apr 07, 1971 • Recording "Dear Boy", "Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey"

Single Apr 12, 1971 • "Another Day / Oh Woman Oh Why (Promo)" by Paul McCartney released in the US

Interview Apr 16, 1971 • Paul McCartney interview for Life Magazine

Article Apr 25, 1971 • John Lennon, George Harrison, Ringo Starr decide not to appeal High Court order

Article May - June 1971 • Paul McCartney starts thinking about a new band

Next interview May 08, 1971 • Paul McCartney interview for New Musical Express

AlbumThis interview was made to promote the "Ram" LP.

Jun 16, 1967 • From Life Magazine

Aug 28, 1968 • From Life Magazine

The case of the missing Beatles - Paul is still with us

Nov 07, 1969 • From Life Magazine

The interview below has been reproduced from this page. This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

Read interview on Life Magazine

I love my life now because I’m doing much more ordinary things, and to me that brings great joy. We’re more ordinary than ordinary people sometimes.

Paul McCartney

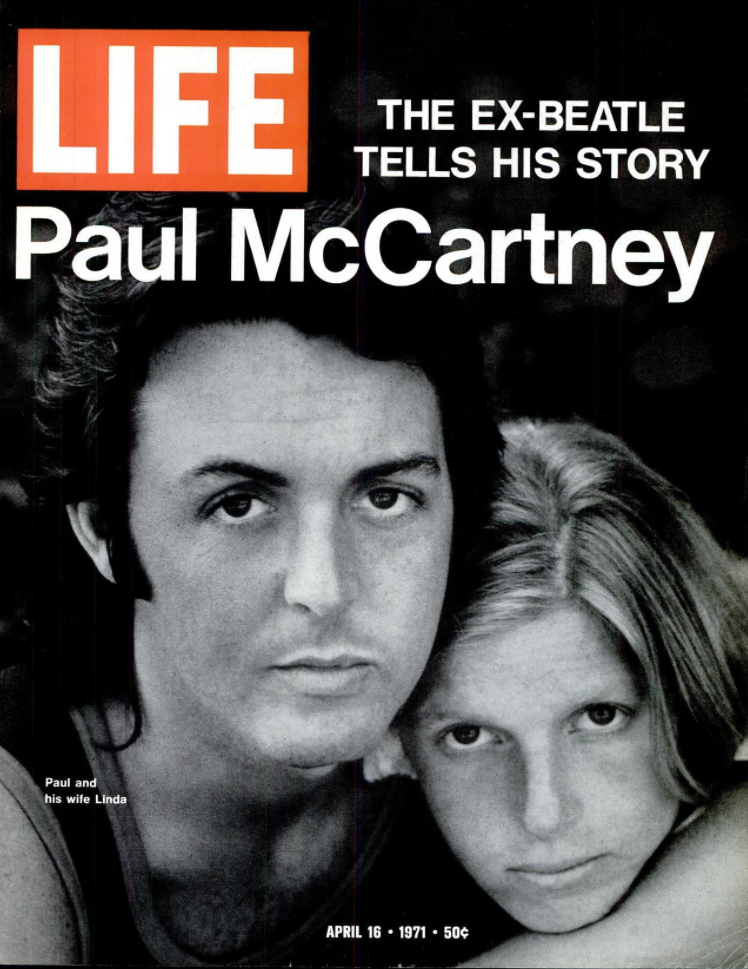

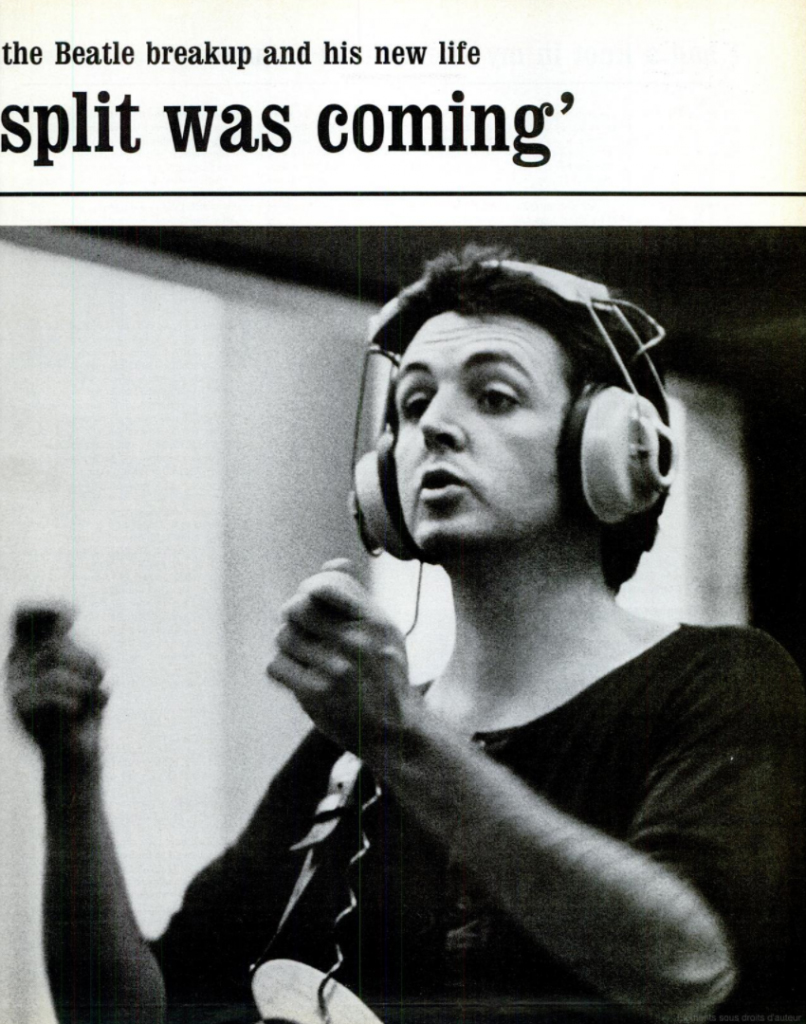

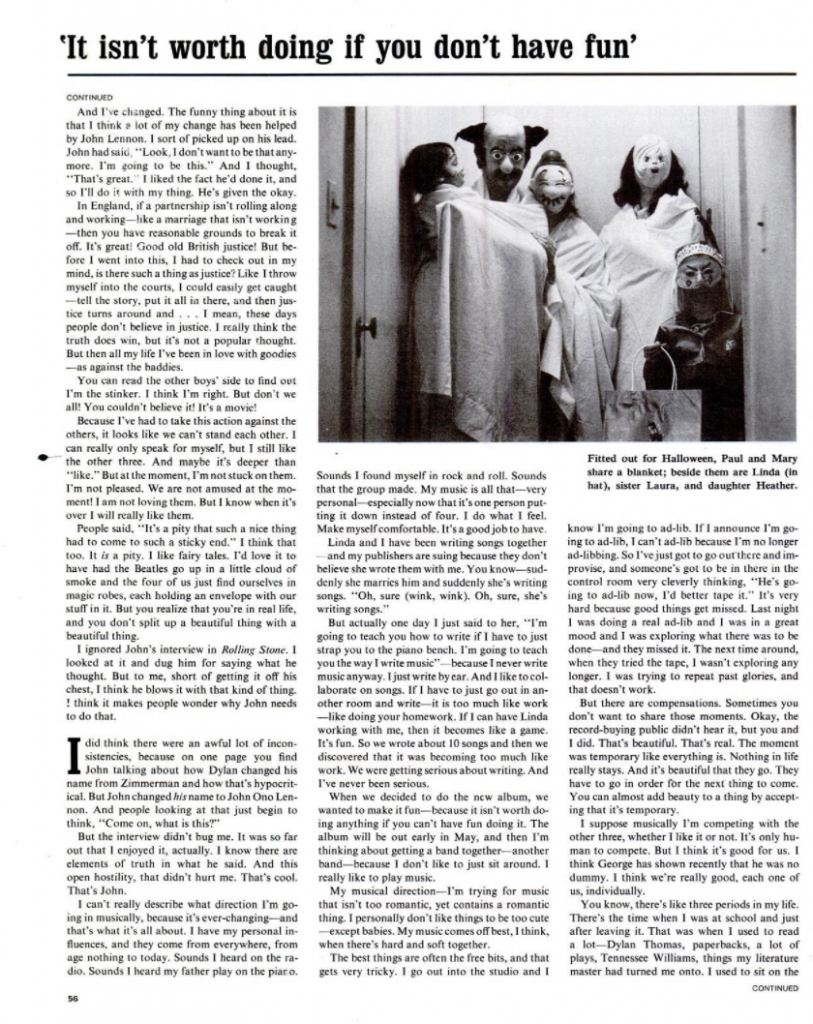

McCartney was interviewed in Los Angeles, during a recording session for his new album Ram. The album, which was partly recorded in New York, contains 11 new songs by Paul, including several written in collaboration with his wife Linda. It is scheduled for release May 15.

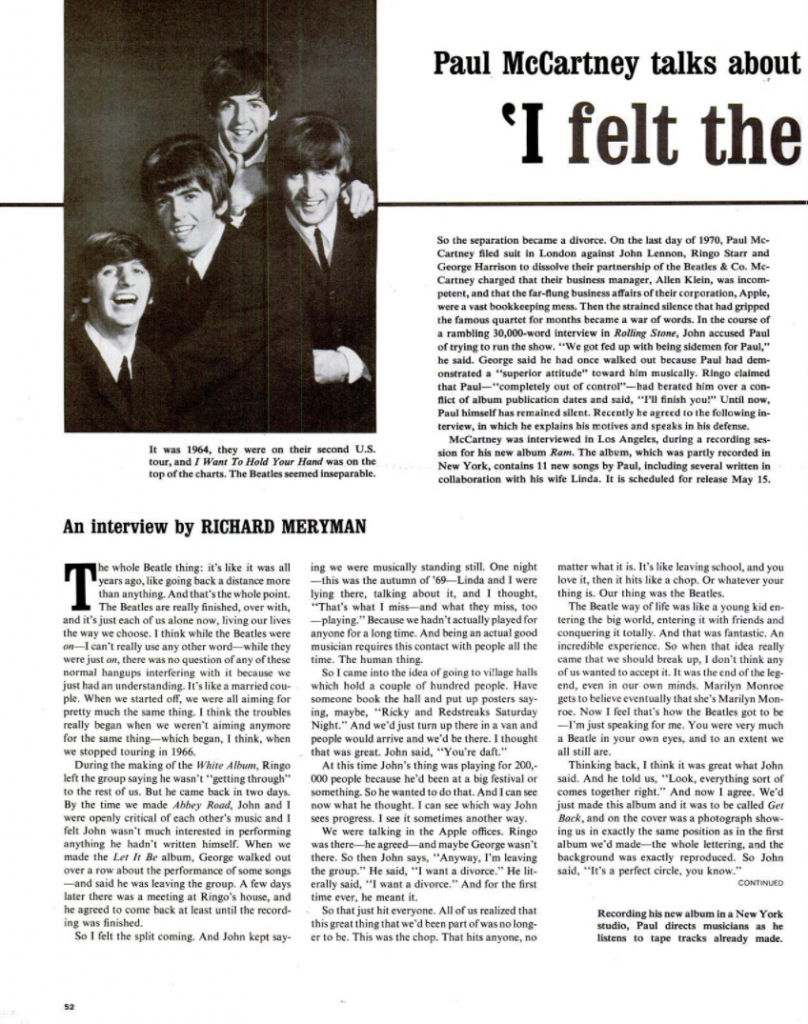

PAUL: “The whole Beatle thing — it’s like it was all years ago — like going back a distance more than anything. And that’s the whole point. The Beatles are really finished, over with, and it’s just each of us alone now, living our lives the way we choose. I think while the Beatles were on — I can’t really use any other word — while they were just on, there was no question of any of these normal hangups interfering with it because we just had an understanding. It’s like a married couple. When we started off we were all aiming for pretty much the same thing. I think the troubles really began when we weren’t aiming anymore for the same thing, which began, I think, when we stopped touring in 1966. During the making of the White Album, Ringo left the group saying he wasn’t ‘getting through’ to the rest of us. But he came back in two days. By the time we made Abbey Road, John and I were openly critical of each other’s music and I felt John wasn’t much interested in performing anything he hadn’t written himself. When we made the ‘Let It Be’ album, George walked out over a row about the performance of some songs — and said he was leaving the group. A few days later there was a meeting at Ringo’s house, and he agreed to come back at least until the recording was finished.”

“So I felt the split coming. And John kept saying we were musically standing still. One night — this was the autumn of ’69 — Linda and I were lying there, talking about it, and I thought, ‘That’s what I miss, and what they miss too — Playing.’ Because we hadn’t actually played for anyone for a long time. And being an actual good musician requires this contact with people all the time. The human thing. So I came into the idea of going to village halls which hold a couple of hundred people. Have someone book the hall and put up posters saying, maybe, ‘Ricky and Redstreaks, Saturday Night.’ And we’d just turn up there in a van and people would arrive and we’d be there. I thought that was great. John said, ‘You’re daft.'”

“At this time John’s thing was playing for 200,000 people because he’d been at a big festival or something. So he wanted to do that. And I can see now what he thought. I can see which way John sees progress. I see it sometimes another way.”

“We were talking in the Apple offices. Ringo was there — he agreed — and maybe George wasn’t there. So then John says, ‘Anyway, I’m leaving the group.’ He said, ‘I want a divorce.’ He literally said, ‘I want a divorce.’ And for the first time ever, he meant it. So that just hit everyone. All of us realized that this great thing that we’d been part of was no longer to be. This was the chop. That hits anyone, no matter what it is. It’s like leaving school, and you love it then it hits like a chop. Or whatever your thing is. Our thing was the Beatles.”

“The Beatle way of life was like a young kid entering the big world, entering it with friends and conquering it totally. And that was fantastic. An incredible experience. So when that idea really came that we should break up, I don’t think any of us wanted to accept it. It was the end of the legend, even in our own minds. Marilyn Monroe gets to believe eventually that she’s Marilyn Monroe. Now I feel that’s how the Beatles got to be — I’m just speaking for me. You were very much a Beatle in your own eyes, and to an extent we all still are. Thinking back, I think it was great what John said. And he told us, ‘Look everything sort of comes together right.’ And now I agree. We’d just made this album and it was to be called ‘Get Back’ and on the cover was a photograph showing us in exactly the same position as in the first album we’d made — the whole lettering and the background was exactly reproduced. So John said, ‘It’s a perfect circle, you know.’ I think what John did was tremendous from the point of view of ‘Okay, so we are actually going to go our own ways.’ You just can’t be as tied together as we were for so long a period of time, unless you all live in the same house. From then onward it was to be a question of living your own life, which was the first real turn-on for me in a long time — and this coincided with my meeting Linda. So early in 1970 I phoned John and told him I was leaving the Beatles too. He said, ‘Good! That makes two of us who have accepted it mentally.'”

“I do think if it were just up to the four of us, if we were totally unencumbered, we would have had a dissolution — I hate these heavy terms — the day after John said he was leaving. We would have picked up our bags — these are my shoes, that’s my ball, that’s your ball — and gone. And I still maintain that’s the only way, to actually go and do that, no matter what things are involved on a business level. But of course we aren’t four fellows. We are part of a big business machine. Even though the Beatles have really stopped, the Beatle thing goes on– repackaging the albums, putting tracks together in different forms, and the video coming in. So that’s why I’ve had to sue in the courts to dissolve the Beatles, to do on a business level what we should have done on a four-fellows level. I feel it just has to come. We used to get asked at press conferences, ‘What are you going to do when the bubble bursts?’ When I talked to John just the other day, he said something about, ‘Well, the bubble’s going to burst.’ And I said, ‘It has burst. That’s the point. That’s why I’ve had to do this, why l had to apply to the court. You don’t think I really enjoy doing that kind of stuff. I had to do it because the bubble has burst– everywhere but on paper.’ That’s the only place we’re tied now.”

“You see, there was a partnership contract put together years ago to hold us together as a group for 10 years. Anything anybody wanted to do — put out a record, anything — he had to get the others’ permission. Because of what we were then, none of us ever looked at it when we signed it. We signed it in ’67 and discovered it last year. We discovered this contract that bound us for 10 years. So it’s ‘Oh gosh, Oh golly, Oh heck,’ you know. ‘Now, boys, can we tear it up, please?’ But the trouble is, the other three have been advised not to tear it up. They’ve been advised that if they tear it up, there will be serious, bad consequences for them. The point, though, to me was that it began to look like a three-to-one vote, which is what in fact happened at a couple of business meetings. It was three to one. That’s how Allen Klein got to be the manager of Apple, which I didn’t want. But they didn’t need my approval.”

“Listen, it’s not the boys. It’s not the other three. The four of us, I think, still quite like each other. I don’t think there is bad blood, not from my side anyway. I spoke to the others quite recently and there didn’t sound like any from theirs. So it’s a business thing. It’s Allen Klein. Early in ’69 John took him on as business manager and wanted the rest of us to do it too. That was just the irreconcilable difference between us.”

“Klein is incredible. He’s New York. He’ll say ‘Waddaya want? I’ll buy it for you.’ I guess there’s alot I really don’t want to say about this, but it will come out because we had to sort of document the stuff for this case. We had to go and fight — which I didn’t want, really. All summer long in Scotland I was fighting with myself as to whether I should do anything like that. It was murderous. I had a knot in my stomach all summer. I tried to think of a way to take Allen Klein to court, or to take a businessman to court. But the action had to be brought against the other three.”

“I first said, ‘No, we can’t do that. We’ll live with it.’ But all those little things kept happening, such trivia compared to what has happened, but the kind of things that… well, for example, my record McCartney came out. Linda and I did it totally — the record, the cover the ads — everything presented to the record company. Then there started to appear these little advertisements. On the bottom was ‘On Apple Records,’ which was okay. But somebody had also come along and slapped on ‘An Abkco-managed company.’ Now that is Klein’s company and has nothing to do with my record. It’s like Klein taking part of the credit for my record.”

“Maybe that sounds petty, but I can go into other examples of this kind of thing. The build-up is the thing — All these things continuously happening making me feel like I’m a junior with the record company, like Klein is the boss and I’m nothing. Well, I’m a senior. I figure my opinion is as good as anyone’s, especially when it’s my thing. And it’s emotional. You feel like you don’t have any freedom. I figured I’d have to stand up for myself eventually or get pushed under. The income from the McCartney album is still being held by Apple, and Linda and I are the only ones on the record. John has a new record out with a song called ‘Power to the People.’ There’s a line in it — sort of shouting to the government — ‘Give us what we own.’ And to me Apple’s the government thing. Give me what I own.”

“So then we began to talk again about the suit, over and over. I just saw that I was not going to get out of it. From my last phone conversation with John, I think he sees it like that. He said, ‘Well, how do you get out?'”

“My lawyer, John Eastman, he’s a nice guy and he saw the position we were in, and he sympathized. We’d have these meetings on top of hills in Scotland, we’d go for long walks. I remember when we actually decided we had to go and file suit. We were standing on this big hill which overlooked a loch — it was quite a nice day, a bit chilly — and we’d been searching our souls. Was there any other way? And we eventually said, ‘Oh, we’ve got to do it.’ The only alternative was seven years with the partnership — going through those same channels for seven years.”

“And I’ve changed. The funny thing about it is that I think a lot of my change has been helped by John Lennon. I sort of picked up on his lead. John had said, ‘Look, I don’t want to be that anymore. I’m going to be this.’ And I thought, ‘That’s great.’ I liked the fact he’d done it, and so I’ll do it with my thing. He’s given the okay. In England, if a partnership isn’t rolling along and working — like a marriage that isn’t working– then you have reasonable grounds to break it off. It’s great! Good old British justice! But before I went into this, I had to check out in my mind, is there such a thing as justice? Like I throw myself into the courts I could easily get caught — tell the story, put it all in there, and then justice turns around and… I mean, these days people don’t believe in justice. I really think the truth does win, but it’s not a popular thought. But then all my life I’ve been in love with goodies, as against the baddies.”

“You can read the other boys’ side to find out I’m the stinker. I think I’m right. But don’t we all! You couldn’t believe it! It’s a movie! Because I’ve had to take this action against the others, it looks like we can’t stand each other. I can really only speak for myself, but I still like the other three. And maybe it’s deeper than ‘like.’ But at the moment, I’m not stuck on them. I’m not pleased. We are not amused at the moment! I am not loving them. But I know when it’s over I will really like them.”

“People said, ‘It’s a pity that such a nice thing had to come to such a sticky end.’ I think that too. It is a pity. I like fairy tales. I’d love it to have had the Beatles go up in a little cloud of smoke and the four of us just find ourselves in magic robes, each holding an envelope with our stuff in it. But you realize that you’re in real life, and you don’t split up a beautiful thing with a beautiful thing. I ignored John’s interview in Rolling Stone (1971). I looked at it and dug him for saying what he thought. But to me, short of getting it off his chest, I think he blows it with that kind of thing. I think it makes people wonder why John needs to do that.”

“I did think there were an awful lot of inconsistencies, because on one page you find John talking about how Dylan changed his name from Zimmerman and how that’s hypocritical. But John changed his name to John Ono Lennon. And people looking at that just begin to think, ‘Come on, what is this?'”

“But the interview didn’t bug me. It was so far out that I enjoyed it, actually. I know there are elements of truth in what he said. And this open hostility, that didn’t hurt me. That’s cool. That’s John.”

“I can’t really describe what direction I’m going in musically, because it’s ever-changing — and that’s what it’s all about. I have my personal influences, and they come from everywhere, from age nothing to today. Sounds I heard on the radio. Sounds I heard my father play on the piano. Sounds I found myself in rock and roll. Sounds that the group made. My music is all that — very personal — especially now that it’s one person putting it down instead of four. I do what I feel. Make myself comfortable. It’s a good job to have.”

“Linda and I have been writing songs together — and my publishers are suing because they don’t believe she wrote them with me. You know, suddenly she marries him and suddenly she’s writing songs. ‘Oh, sure — wink, wink — Oh, sure, she’s writing songs.’ But actually one day I just said to her, ‘I’m going to teach you how to write if I have to just strap you to the piano bench. I’m going to teach you the way I write music’ — because I never write music anyway. I just write by ear. And I like to collaborate on songs. If I have to just go out in another room and write — it is too much like work — like doing your homework. If I can have Linda working with me, then it becomes like a game. It’s fun. So we wrote about 10 songs and then we discovered that it was becoming too much like work. We were getting serious about writing. And I’ve never been serious.”

“When we decided to do the new album, we wanted to make it fun, because it isn’t worth doing anything if you can’t have fun doing it. The album will be out early in May, and then I’m thinking about getting a band together — another band — because I don’t like to just sit around. I really like to play music.”

“My musical direction — I’m trying for music that isn’t too romantic, yet contains a romantic thing. I personally don’t like things to be too cute — except babies. My music comes off best, I think, when there’s hard and soft together.”

“The best things are often the free bits, and that gets very tricky. I go out into the studio and I know I’m going to ad-lib. If I announce I’m going to ad-lib, I can’t ad-lib because I’m no longer ad-libbing. So I’ve just got to go out there and improvise, and someone’s got to be in there in the control room very cleverly thinking, ‘He’s going to ad-lib now, I’d better tape it.’ It’s very hard because good things get missed. Last night I was doing a real ad-lib and I was in a great mood and I was exploring what there was to be done — and they missed it. The next time around when they tried the tape, I wasn’t exploring any longer. I was trying to repeat past glories, and that doesn’t work. But there are compensations. Sometimes you don’t want to share those moments. Okay, the record-buying public didn’t hear it, but you and I did. That’s beautiful. That’s real. The moment was temporary like everything is. Nothing in life really stays. And it’s beautiful that they go. They have to go in order for the next thing to come. You can almost add beauty to a thing by accepting that it’s temporary.”

“I suppose musically I’m competing with the other three, whether I like it or not. It’s only human to compete. But I think it’s good for us. I think George has shown recently that he was no dummy. I think we’re really good, each one of us, individually. You know, there’s like three periods in my life. There’s the time when I was at school and just after leaving it. That was when I used to read alot — Dylan Thomas, paperbacks, alot of plays, Tennessee Williams, things my literature master had turned me onto. I used to sit on the top level of buses, reading and smoking a pipe. Then there was the whole sort of Beatle thing. And just now again I feel I can do what I want. So it’s like there was me, then the Beatles phase, and now I’m me again.”

“It’s rather serious — life. And you can’t live as if you have nine lives. I find myself doing that often. I think everybody does, saying in his mind, ‘I’ll get it tomorrow.’ But I can’t do that anymore. Take One with the Beatles should have been like I said, with a puff of smoke and magic robes and envelopes. But we missed Take One, so now we do Take Two. And in the disappointment of Take Two — I feel I can always find something good in the bad — the good thing is that it really has made me come to terms more with my life. As a married couple, Linda and I’ve really become closer because of all those problems, all the decisions. It’s been very real what I’ve been through — a breath of air, in a way — because of having been through very inhuman things.”

“The Beatle thing was fantastic. I loved every minute of it. It was beautiful. But it was a very sheltered life. Why, somebody would even ring me up in the morning and say, ‘You’ve got to be at Apple in an hour.’ It got very nursemaidy. If you are a real human, you’ve got to wake yourself up. You’ve got to take on these tedious little things because out of the tedium comes the joy of life. I got fed up by Apple this year over Christmas trees. ‘Did we want one, because the office was buying Christmas trees for everyone?’ I hated that. Actually we pinched one from a field in Scotland.”

“I love my life now because I’m doing much more ordinary things, and to me that brings great joy. We’re more ordinary than ordinary people sometimes.”

“In New York, we go to Harlem on the subway — a great evening at the Apollo. We walk through Central Park after hours. You may find us murdered one day. Last time we went it was snowy like moonlight in Vermont — just fantastic. And I figure anyone who scares me, I scare him.”

“We try never to organize our lives very much. We do things on the spur of the moment. We were in Scotland and we decided to take a trip to the Shetland Islands. So we piled in the Land Rover with the two kids, our English sheep dog, Martha, and a whole pile of stuff in the back with Mary’s potty on the top. On the second day we get up to a little port called Scrabster at the top of Scotland. When we tried to get on the big car ferry, we got in queue but were two cars too late — missed it. So, don’t despair. Okay, make the best of it. We really didn’t want to go on that big liner, a mass-produced thing. So we thought, let’s beat the liner. But we gave that up — it became a bit difficult with airplanes and such. Let’s try to get a ride in one of the little fishing boats, and how much should we offer.”

“So the romantic idea was that they’d rather have a salmon or a bottle of Scotch than the 30 pounds. I went to a bunch of boats but they weren’t going to the Orkney Islands. So I went on this one and I went to this trapdoor sort of thing, and they were sleeping down below — the smell of sleep is coming up through the door. At first the skipper said no, and then I said there was 30 quid in it for him, and they say they’ll take us. It was a fantastic little boat called the Enterprise and the captain named George, he’s wearing a beautiful Shetland sweater. We brought all our stuff aboard and it was low tide, so we had to lower Martha in a big fishing net and a little crowd gathers and we wave our farewells. As we steam out, the skipper gives us some beer, and Linda, trying to be one of the boys takes a swig and passes it to me. Well, you shouldn’t drink before a rough crossing to the Orkneys. The little one, Mary, throws up all over the wife, as usual. That was it. I was already feeling sick. I sort of gallantly walked to the front of the boat, hanging onto the mast. The skipper comes up and we’re having light talk, light chit-chat. And I don’t want it. So he gets the idea and points to the fishing baskets and says, ‘Do it in there!’ So we were all sick, but we ended up in the Orkney Islands, and we took a plane to Shetland. It was great.”

“We do things like that — do it sort of eccentricordinary because we have got the money to do it eccentric. I always wondered what happened to those maharajahs who used to do things. But there never are really any of those people. So we try and do a bit of it in our own lives.”

“People do recognize us sometimes, but they respect our privacy. It’s a beautiful thing. If you come on as a star, you get star treatment and all the disadvantages. But often, when we dress in dungarees and sneakers — Last night we got turned out of two restaurants. The guy in an evening suit turns us out. But I quite like it when they chuck us out.”

“I love to find that, even in this day of concrete, there are still alive horses and places where grass grows in unlimited quantities and sky has got clear air in it. Scotland has that. It’s just there without anyone touching it. It just grows. I’m relieved to find that it isn’t all pollution. It isn’t all the Hudson. It’s not all the drug problem. When we are in Scotland we plant stuff — vegetables — and we’ll leave them there, and of their own volition they will push up. And not only will they push up and grow into something, but then they will be good to eat. To me that’s an all-time thing. That’s fantastic. How clever! Just that things push their own way up and they feed you. We don’t eat meat because we’ve got lambs on the farm, and we just ate a piece of lamb one day and suddenly realized we were eating a bit of one of those things that was playing outside the window, gamboling peacefully. But we’re not strict. I don’t want to put a big sign on me, ‘Thou Shalt Be Vegetarian.’ I like to allow myself. I like to give myself a lucky break. Give yourself a lucky break, son.”

“So I think you’ve got to live your own life. That sounds like one of those statements, but it is, in fact, just very necessary to realize that. And particularly necessary for me. Or else someone else is going to be living part of your life for you. But now I would like to stop talking and get up and get to work. I haven’t done any today, and it’s beginning to frustrate me. I’ve got that album to finish. We’ve got to get back to plant the seeds. Nature doesn’t wait.”

I met Linda Eastman in a New York photo lab, getting some films developed, and we got to be friendly over lunch. Then one day, I read that she’d married Paul McCartney. I was like, ‘Wow, go figure!’

A year later, I got a call from her and she said, ‘Henry, we’re out in Malibu, and we need some pictures for the RAM album’. So I went out and spent the afternoon sitting around the swimming pool, eating lunch, with the little girls Heather and Mary.

As I was taking pictures, Paul was sitting in a deck chair, plucking on his ukulele. I saw Heather and Mary hold hands and jump into the pool together. Without stopping, Paul started singing, ‘Two little sisters jumping in the pool’. It was a beautiful little melody and I thought, oh my God, there’s a Beatles song that only I will ever hear.

Towards the end of the day, Linda told me, ‘We need a nice portrait of the two of us’, so we went over, brought some flowers and took the pictures. Then she said, ‘We need these first thing in the morning because we want to send one to Life magazine’.

Life magazine was the Holy Grail for photographers, so of course I got there early. This was 1971, before scanning and emailing, so the lady from Life magazine was there, in the living room. She looked through the pictures on a slide board, picked one, put it in her purse, went to the airport and flew to New York with it. And that was the cover.”

Henry Diltz – From Henry Diltz: Rock’s ‘accidental photographer’ wins lifetime achievement prize – BBC News

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.