Timeline

More from year 1990

Songs mentioned in this interview

Officially appears on Hey Jude / Revolution

Officially appears on I Feel Fine / She's A Woman

Officially appears on Please Please Me (Mono)

Officially appears on Let It Be / You Know My Name (Look Up The Number)

Officially appears on She Loves You / I'll Get You

Interviews from the same media

Aug 31, 1972 • From RollingStone

Paul McCartney: The Rolling Stone Interview

Jan 31, 1974 • From RollingStone

Jun 17, 1976 • From RollingStone

Paul McCartney by Paul Gambaccini

Mar 30, 1979 • From RollingStone

Paul McCartney: Ten Days in the Life

Feb 20, 1980 • From RollingStone

Paul McCartney: The Rolling Stone Interview

Sep 11, 1986 • From RollingStone

Jun 15, 1989 • From RollingStone

Feb 10, 1994 • From RollingStone

Paul McCartney on 'Beatles 1,' Losing Linda and Being in New York on September 11th

Dec 06, 2001 • From RollingStone

Oct 20, 2005 • From RollingStone

Spread the love! If you like what you are seeing, share it on social networks and let others know about The Paul McCartney Project.

Interview

The interview below has been reproduced from this page . This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

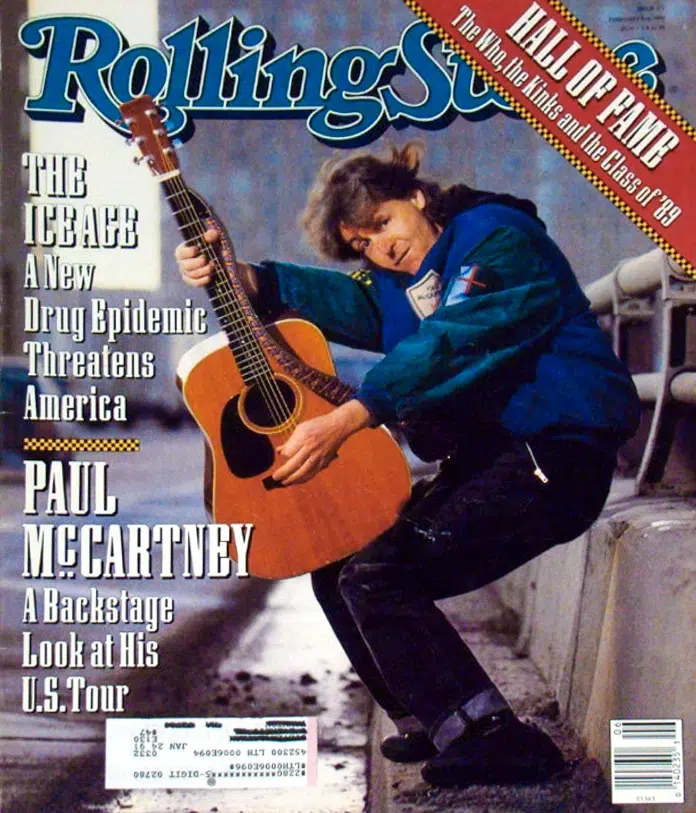

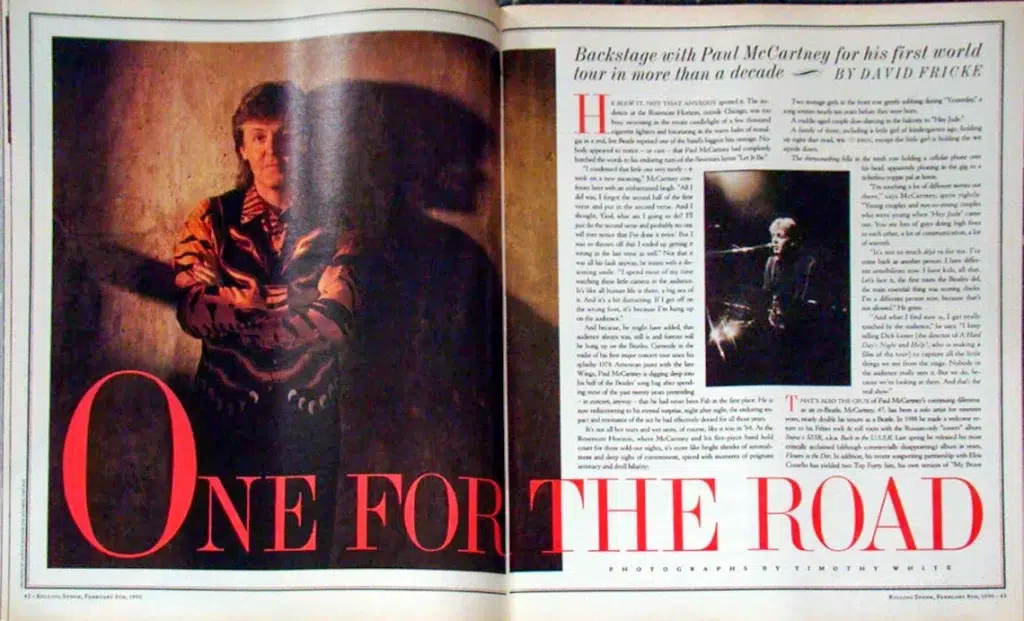

He blew it. Not that anybody spotted it. The audience at the Rosemont Horizon, outside Chicago, was too busy swooning in the ersatz candlelight of a few thousand cigarette lighters and luxuriating in the warm balm of nostalgia as a real, live Beatle reprised one of the band’s biggest hits onstage. Nobody appeared to notice — or care — that Paul McCartney had completely botched the words to his enduring turn-of-the-Seventies hymn “Let It Be.”

“I condensed that little one very nicely — it took on a new meaning,” McCartney confesses later with an embarrassed laugh. “All I did was, I forgot the second half of the first verse and put in the second verse. And I thought, ‘God what am I going to do? I’ll just do the second verse and probably no one will ever notice that I’ve done it twice.’ But I was so thrown off that I ended up getting it wrong in the last verse as well.” Not that it was all his fault anyway, he insists with a disarming smile. “I spend most of my time watching these little cameos in the audience. It’s like all human life is there, a big sea of it. And it’s a bit distracting. If I get off on the wrong foot, it’s because I’m hung up on the audience.”

And because, he might have added, that audience always was, still is and forever will be hung up on the Beatles. Currently in the midst of his first major concert tour since his splashy 1976 American jaunt with the late Wings, Paul McCartney is digging deep into his half of the Beatles’ song bag after spending most of the past twenty years pretending — in concert, anyway — that he had never been Fab in the first place. He is now rediscovering to his eternal surprise, night after night, the enduring impact and resonance of the act he had effectively denied for all those years.

It’s not all hot tears and wet seats, of course, like it was in ’64. At the Rosemont Horizon, where McCartney and his five-piece band hold court for three sold-out nights, it’s more like bright shrieks of astonishment and deep sighs of contentment, spiced with moments of poignant intimacy and droll hilarity:

Two teenage girls in the front row gently sobbing during “Yesterday,” a song written nearly ten years before they were born.

A middle-aged couple slow-dancing in the balcony to “Hey Jude.”

A family of three, including a little girl of kindergarten age, holding up signs that read, “We ♥ Paul,” except the little girl is holding the “We” upside down.

The thirtysomething fella in the tenth row holding a cellular phone over his head, apparently phoning in the gig to a ticketless yuppie pal at home.

“I’m touching a lot of different nerves out there,” says McCartney, quite rightly. “Young couples and not-so-young couples who were young when ‘Hey Jude’ came out. You see lots of guys doing high fives to each other, a lot of communication, a lot of warmth.

“It’s not so much déjà vu for me. I’ve come back as another person. I have different sensibilities now. I have kids, all that. Let’s face it, the first tours the Beatles did, the main essential thing was scoring chicks. I’m a different person now, because that’s not allowed” He grins.

“And what I find now is, I get really touched by the audience,” he says. “I keep telling Dick Lester [the director of A Hard Day’s Night and Help!, who is making a film of the tour] to capture all the little things we see from the stage. Nobody in the audience really sees it. But we do, because we’re looking at them. And that’s the real show.”

That’s also the crux of Paul McCartney’s continuing dilemma as an ex-Beatle. McCartney, 47, has been a solo artist for nineteen years, nearly double his tenure as a Beatle. In 1988 he made a welcome return to his Fifties rock & roll roots with the Russian-only “covers” album Snova v SSSR, a.k.a. Back in the U.S.S.R. Last spring he released his most critically acclaimed (although commercially disappointing) album in years, Flowers in the Dirt. In addition, his recent songwriting partnership with Elvis Costello has yielded two Top Forty hits, his own version of “My Brave Face” and Costello’s recording of “Veronica.” He capped 1989 by debuting a fine, new touring band featuring top-drawer studio and road guys who could outplay Wings blindfolded — guitarist Robbie McIntosh (the Pretenders), singer-guitarist Hamish Stuart (Average White Band), keyboardist Paul “Wix” Wickens (Paul Young, the The) and drummer Chris Whitten (the Waterboys, Julian Cope), plus McCartney’s wife, Wings vet Linda, on keys and harmonies.

Yet it has hardly escaped McCartney’s attention that many of the people packing arenas and, later this spring, stadiums on his 1989-90 world tour are not coming to see him play obscure album tracks from Flowers in the Dirt. They are coming to see the Beatles-by-proxy. They are coming to have their emotional buttons pushed by the songs that defined and transformed their youth — “The Long and Winding Road,” “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” “Good Day Sunshine,” “Things We Said Today,” “Back in the U.S.S.R.,” “I Saw Her Standing There,” the climactic “Golden Slumbers/Carry That Weight/The End” medley from Abbey Road. They are coming to see many of these songs performed live for the first time (the bulk of the Beatles oldies in McCartney’s show postdate their 1966 retirement from the stage) and, quite possibly, the last.

At the Rosemont Horizon and later that week at the Skydome in Toronto and at the Forum in Montreal, you could feel the audience buzz take a palpable dip every time McCartney went into an unfamiliar number from Flowers in the Dirt, like the reggaefied shuffle “Rough Ride” or “We Got Married,” a Flowers highlight recalling the hard-rock melodrama of mid-Seventies Wings. The pressure drop was particularly noticeable at the beginning of the two-and-a-half-hour show, as the crowd cheered the soundtrack of Beatles, Wings and solo McCartney hits that accompanied Richard Lester’s opening rockumentary-film montage with its kinetic blasts of Beatlemania, flower power, Vietnam, et cetera. After which McCartney and his band hit the stage and stepped right into … his new single, the appealing but comparatively low-key “Figure of Eight.”

“We did that on purpose — we had to do that,” McCartney argues over a veggie burger (the McCartneys are devout vegetarians) during a preshow dinner break backstage in Toronto. “Originally, we were going to open with ‘I Saw Her Standing There.’ But I really got upset by the idea. I was going home one night and I thought, ‘That’s really betraying our new material, sending it right down the line.’ Like saying, ‘Hey, I haven’t been around for thirteen years and I haven’t done anything worthwhile. Here’s the Beatles stuff.’

“It’s the obvious thing. Boom, bang, Beatles, Beatles. Then you say, ‘Now we’d like to do some new material.’ Boo! Hiss! I’ve seen the Stones try and do it, and it doesn’t go down that great. That’s a fact of life. Even with the Beatles, new material didn’t always go down that well. It was the older tunes. ‘Baby’s in Black’ never went down nearly as well as ‘I Feel Fine’ or ‘She Loves You.’ That’s just the nature of the beast.

“It is hard to follow my own act,” he admits. “But the only answer to that would be to give up after the Beatles. I only had two alternatives. Give up, or carry on. And having elected to carry on, I couldn’t stop.”

McCartney has been consistently productive as an ex-Beatle. He has not, however, been consistently successful. His Eighties chart duds include Pipes of Peace, Give My Regards to Broad Street (the soundtrack to his disastrous feature film of the same name), Press to Play and the solo/Wings “greatest hits” package, All the Best. Notably, McCartney includes only one song from the first three albums in his current show: “Say Say Say,” his Number One duet with Michael Jackson, from Pipes of Peace, is featured in Richard Lester’s opening film.

Flowers in the Dirt has done reasonably well saleswise — 600,000 copies in the United States, 1 million in continental Europe by year’s end — but has not been the chartbuster either McCartney or his manager, Richard Ogden, certainly hoped for. The record went into a particularly bad airplay-and-promo slump in the early fall; the sprightly “This One” was issued as a single to the sound of one hand clapping.

“It was as if it didn’t exist,” Ogden says ruefully. “I sat with a radio program director from Chicago, very nice, very up about the show. And he said, ‘What’s the next single?’ And I said, ‘We’re just starting with “Figure of Eight” ‘ And he said, ‘What about “This One”? That’s really good.’ And I said, ‘That came out in August, mate.’ That really drives me crazy.”

McCartney’s response, says Ogden, is a bit stoic. “Paul’s been doing this for a long time, and he’s going, ‘I don’t want to think about this anymore. You guys sort it out.’” In fact, McCartney’s response to his ongoing Eighties commercial and, until recently, critical slump has been to get out and play, something he had done infrequently (Live Aid, the 1986 Prince’s Trust concert) since Wings broke up following his arrest in Japan in 1980 for possession of marijuana. In 1987, with Ogden’s active encouragement and organization, McCartney initiated a series of Friday-night jam sessions at a suburban-London studio with an eye toward eventually finding enough new, inspiring players to start a formal band. He also liked the idea, he says, of having a rockers’ equivalent of cafe society.

“The Beatles nearly did that once,” says McCartney. “We were going to open an Apple tea room, where we could all go and be intellectual, talk art or Stockhausen. So I thought, ‘We’ll do a similar thing with the jam. Maybe the word will get out that there’s a jam every Friday night, see who shows up.’ But in fact, because it’s done by your office, and they just ring specific people, it didn’t work out like that. Whoever they rang, showed. Whoever they didn’t ring, didn’t show.”

Among those who did show were former Rockpile and Dire Straits drummer Terry Williams, top record producer Trevor Horn (he played bass), Elvis Costello (he was already hanging around for songwriting sessions) and ex-Smiths guitarist Johnny Marr, who borrowed some of his dad’s old records to bone up on McCartney’s favorite Fifties tunes. Out of those Friday jams came the Russian covers album, which was originally cut just to have a memento of the sessions. Drummer Chris Whitten, who played on Snova v SSSR, was the only member of McCartney’s current road band who actually “auditioned” at the jams. But it was a start. Hamish Stuart and Robbie McIntosh subsequently arrived during the recording of Flowers in the Dirt, Wix at the tail end.

When asked why he stayed off the road for so long, McCartney says very casually: “I just couldn’t be bothered. Until Live Aid came along, I didn’t think of doing anything live. I don’t know why. Maybe because nobody asked me. Nobody asked me personally, anyway. I’d hear little things here and there; I heard that Elton John was quoted as saying, ‘What he needs is to get back on the road.’ But it never seemed that vital for me; I was already enjoying myself.”

McCartney was never really much of a road hog. Wings’ first and only American tour came ten years after the Beatles said sayonara to the road at Candlestick Park. And it’s easy to tell how much time has elapsed by watching McCartney’s current show. The production is heavy on Seventies arena kitsch: lasers galore, levitating keyboards. McCartney’s between-song patter also probably seems quaint (“We’re going to go back through the mists of time, to a time known as the Sixties”) to veteran Eighties concertgoers used to the narrative command of Springsteen or Bono’s spiritual cheerleading.

One distinctly Eighties aspect of McCartney’s tour is his controversial tour-sponsorship deal with Visa for the 1990 American shows. The Visa arrangement — reportedly worth $8.5 million, which McCartney says basically covers the cost of transport for the tour — represents a new, potentially troublesome twist in pop-music sponsorship: rock & roll sponsored (some will say co-opted) not simply by a merchandiser but by a credit-card company, with close ties to banks and their complex networks of possibly questionable investments. McCartney says he vetted Visa as thoroughly as possible before saying, “I do.” “It may be true that they are a gigantic money corporation,” he says, “but I can’t see what’s wrong with that, unless you can prove to me South African links.”

McCartney also insists he is not betraying any kind of political, social or emotional trust represented by the Beatles or the songs of theirs that he’s performing on tour. “Whether you like it or not,” he says, “no matter what people thought was going on in the Sixties, every single band that did anything got paid for it. You look back at the early Beatles concert programs, there were Coke ads. We always got paid for everything we did, and when we made a deal, we always wanted the best.

“Somebody said to me, ‘But the Beatles were anti-materialistic.’ That’s a huge myth. John and I literally used to sit down and say, ‘Now let’s write a swimming pool.’ We said it out of innocence. Out of normal, fucking working-class glee that we were able to write a ‘swimming pool.’ For the first time in our lives, we could actually do something and earn money.

“You get any act around the table with their record company, they tell their manager, ‘Go in and kill.’ They don’t say, ‘Oh, let the punters in at half price.’ We’ve actually done a lot of that — the free program, that wasn’t necessary. [According to Richard Ogden, the costs for the program on the 1989 European and American shows totaled about $1 million.]

“And I think it’s just going to be tough if people don’t like it,” he says coolly. “Stick the finger up and say, ‘Sorry, boys, it’s tough. You may not like me because of it. Tough darts. I know I’m not doing it for whatever perception you put on it. It doesn’t alter me.’ I’ve taken money off of EMI. The Beatles took money off of United Artists.

“I wish we’d taken a little more actually,” he says, suddenly laughing, taking some of the chill out of the air. “The accountants on A Hard Day’s Night got three percent. We got a fee.”

I‘m actually getting tired of Paul interviews,” Linda McCartney remarks with a shrug while her husband is being trailed by a television-news crew backstage in Chicago. “People always ask him about the same things. What John said about this, or what such and such Beatles song meant? Why don’t they ask him about other things, about the important things going on in the world?”

For many of the press hounds, radio DJs and TV interviewers following this tour, not to mention the fans who are paying for the privilege, the Beatles are still one of the most important things in the world. In a world still reeling from their original sound and remarkable creative vision, the Beatles’ significance as a cultural touchstone and spiritual anchor cannot be overestimated. In the Sixties the group was the embodiment of youthful ambition and utopian desire amid the graphic realities of war in Southeast Asia and at home in the urban ghettos. Now, with the world plagued by crack, wracked with racial hatred and poised on the edge of ecological apocalypse, talking about the Beatles is like a form of therapy.

That seems to be just as true for McCartney as it is for any fan. During rehearsals for the tour, the band would take an occasional tea break, at which point, Paul Wickens recalls, “anecdotes would come out about the old days, little stories about him and John.”

But the usual aura of Beatlemania that accompanies McCartney wherever he goes has increased tenfold, at least, with the inclusion of so many Beatles songs in his set. The recent settlement of the band members’ lawsuits with their record company, Capitol-EMI, and among themselves has also brought the tiresome issue of a Beatles reunion back to the fore. McCartney himself fanned that flame at the start of the American tour in November when he suggested during a Los Angeles press conference that with their legal differences settled, maybe he and George Harrison might write songs together for the first time. (He didn’t say anything about writing with Ringo Starr.) Harrison quickly put the kibosh on a possible reunion, issuing a terse press statement: “As far as I’m concerned, there won’t be a Beatles reunion as long as John Lennon remains dead.”

Indeed, John Lennon is an extremely conspicuous presence on McCartney’s tour, by his very absence. His name, his music and his celebrated differences with McCartney during and after the Beatles’ lifetime repeatedly come up in both interviews and idle conversation. Lennon figures prominently in the autobiographical passages that constitute the bulk of the 100-page concert program McCartney is distributing gratis at his shows. But in discussing Lennon in the context of his own contributions to the Beatles’ legacy, without Lennon to answer back, McCartney runs the risk of looking like he’s grabbing all the glory.

For example, a portion of the program’s interview section is devoted to McCartney’s adventures in the nascent London underground of the mid-Sixties: hanging out with art scenesters like gallery owner Robert Fraser, attending avant-garde music concerts, helping to set up the pioneering Indica Bookshop and Gallery, funding the seminal underground newspaper IT (International Times). “I’m not trying to say it was all me,” McCartney points out in the program, “but I do think John’s avant-garde period later, was really to give himself a go at what he’d seen me having a go at.”

“Because I talk about this so much, people go around saying, ‘Oh, he’s trying to reclaim the Beatles for himself, to take it away from John,’” says McCartney while relaxing on the chartered jet ferrying him, his family and the band between Toronto and Montreal. “I’m not doing anything of the kind! I’m not trying to claim the history and achievements of the Beatles for myself. I’m just trying to reclaim my part of it.

“It’s not sour grapes. It’s true. I was there in the mid-Sixties when all these things started to happen in London. The Indica Gallery, art people like Robert Fraser. I was living in London, and I was the only bachelor of the four. The others were married and living in the suburbs. I was just there when it all started to happen.

“The difference is that once John got interested in it, he did it like everything else — to extremes. He did it with great energy and enthusiasm. He dove into it headfirst with Yoko. So it looked like he had been the one doing all the avant-garde stuff.

“It’s the ultimate conundrum,” he admits rather helplessly. “If I don’t say anything, I go on being the so-called wimp of the group. If I do open my mouth, it looks like I’m sullying John.

“And this has only become an issue because he’s dead. Because of the mythologizing that inevitably comes with someone as special as that. And he never wanted that for himself. I remember driving in a car, listening to an interview with John on the radio on the day he died in which he said, ‘I don’t want to be a martyr.’ He didn’t want that responsibility, to be larger than life, to be some kind of god.”

No one brings it up, but this discussion, ironically enough, is taking place on the evening of the ninth anniversary of John Lennon’s murder.

“The fact is, we were a team,” McCartney states firmly as the plane begins its descent, “despite everything that went on between us and around us. And I was the only songwriter he ever chose to work with. Nuff said.”

A day in the touring life, McCartney style, is a nonstop series of interviews, photo opportunities, press conferences, sound checks and meals grabbed quickly by a band on the run. And, of course, the nights are busy, too.

This evening’s performance at Toronto’s Skydome includes McCartney’s nightly plug for Friends of the Earth, the international ecological lobbying group that he is promoting throughout the tour. As the final notes of the closing Abbey Road medley reverberate around the cavernous Skydome, McCartney and the band jump into a fleet of golf carts, which zoom through the hallways to a waiting tour bus. With all aboard, the bus pulls out of the Skydome Starsky and Hutch-style before most of the fans have even left their seats. Back at the hotel at 1:00 a.m., McCartney hosts a small bash for the tour entourage in his suite. The food is vegetarian Chinese. The main attraction is a video of the evening’s Sugar Ray Leonard-Roberto Duran fight. At 2:30 a.m., as the party breaks up, McCartney, wearing a bathrobe, dances alone in the living room to the new Quincy Jones album.

Sedate in tone, organized with stunning military efficiency, the 1989-90 Paul McCartney World Tour is strictly business — the business of putting on a good show, promoting the latest record, getting maximum publicity and attempting to satisfy the constant public hunger for all things Beatle.

“This is more like a Beatles tour, strangely enough,” says McCartney. “In doing this tour, I’ve taken hints. If someone comes up and says, ‘How should we do this?’ my mind goes back to the best tours I’ve been on. And those were the first Beatles tours of America. They were highly organized, very efficient.

“And if you’re going to go on tour, it doesn’t hurt to do press. I just started talking about ‘Well, in the Beatles, we used to do press conferences.’ So when we were doing warm-up shows in Europe, they had a lot of people who wanted to talk to me. So I said, ‘Why don’t we do press conferences?’ It’s all those little ingredients, looking back on the Beatles things, seeing what was good about it.”

Where there was once the hysteria of four wild boys with the world at their feet, however, now there is the calm of a middle-aged man who spends nearly all of his offstage hours meeting with assorted advisers, attending to his family (he and Linda are accompanied on this series of shows by two of their four children, Stella and James) and in turn being attended to by personal staff and security, the most prominent of the latter being three muscular, well-dressed men who look as if they had graduated with honors from Secret Service finishing school. Hell raising, needless to say, is at a premium on this tour.

“I’m not used to that,” Robbie McIntosh says of the tour’s emphasis on organization. “When I was with the Pretenders, we would do a sound check and then we would go to a pub or something. Now with this, I get a feeling I can’t do that. It’s a lot more regimented, basically because the security is a lot heavier, because of who Paul is. And I guess because of what happened to John, although nobody directly mentions that.”

Not that McCartney is a killjoy on the road. McIntosh observes that the band “is sort of sacred” to McCartney, wholly separate from business. “He never talks business. Never, ever. He’s never mentioned money or anything like that to me. If he’s got something to say, then he’ll say it to the manager, and you will get it from him.

“And he’s got a very young approach as far as the band,” says McIntosh “You’d think this is his first band the way he goes on. You see him at sound checks, going around in circles and doing those silly little jumps. It’s a real novelty to him to have a band again — and he treats it like that.”

The sound checks are shows in themselves. McCartney doesn’t run through any of the songs in the regular production; instead, he leads the band through a batch of oldies (Carl Perkins’s “Matchbox,” an old Beatles cover, and tracks from the Russian album, like “Just Because” and “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore”), the Wings B side “C Moon,” the jaunty British music-hall number “Me Father Upon the Stage” and a Latin-hustle medley of Beatles songs.

“He’s a real clown,” Wix says quite admiringly. “He loves to show off, and he loves to be there doing it, making people laugh.”

And sure enough, onstage you can see by the light of his beaming, vintage Beatle Paul smile and the way he throws himself into the sixteen Beatles songs featured in the show that no one is enjoying this forward-into-the-past expedition more than McCartney himself.

“It’s twenty years, man,” McCartney says a bit wearily in response to the questions that have dogged him the whole length of the tour — why Beatles songs, and why so many?

“You can’t keep angry forever, twenty years after an event that hurt,” he says, referring to the band’s acrimonious breakup. “Time is a great healer.”

McCartney explains that in preparation for the tour he actually sat down with pen and paper and drew up a list of his favorite Paul McCartney songs, Beatles and otherwise. He came up with so many of them that at one point there was talk, briefly anyway, of doing two completely different shows in each city. “I’d said to myself, ‘You’re a composer,’” he says. “‘There’s no shame in doing these songs.’”

The songs of late partner John Lennon were a different matter. “In fact, I considered doing a major tribute to John,” says McCartney. “But it suddenly felt too precious, too showbiz. I was going to have a whacking great picture of John and just say, ‘He was my friend.’ Which was true. I’m totally proud to have worked with him.

“But then people started saying, ‘Why don’t you do “Imagine”?’ And I thought, ‘Fucking hell, Diana Ross does “Imagine.” They all do “Imagine.”‘ That’s when I backed off the whole thing. You go on tour, you sing your songs, arrange ’em nice, do it, and if you do it well enough, that’s what people will remember.”

Paul McCartney was rather late out of the starting gate for the 1989 Dinosaurs on the Road Sweepstakes, eating the dust already kicked up during the summer and early fall by the Who, the Rolling Stones and even Ringo Starr. But he’s not bugged either about his membership in the club — “I’m another dinosaur,” he says frankly — or by the implicit pressure to prove his viability as a contemporary artist to an audience obsessed by his past, if necessary at the expense of his peers.

“It’s never stopped,” says McCartney, sitting on a bench in the Montreal Canadiens’ locker room while a sold-out house awaits him inside the Forum next door. “I will never stop competing with every other artist in this business. Pet Sounds kicked me to make Pepper. It was direct competition with the Beach Boys. So what? That’s what everyone’s doing. Although when Brian Wilson heard Pepper, he went the other way.

“But, yeah, it’s competition. If you put ten children in a room, after an hour or so, they’ll sort themselves out. The smart one. The big, tough one. The cowardly one. The funny one who’s the friend of the smart one and the big, tough one. They will establish a pecking order.”

And where does McCartney place himself in rock’s pecking order?

“I’d put me at the top. Just because I’m a competitor, man. You don’t have Ed Moses going around saying, ‘Sure, I’m the third-best hurdler in the world.’ You don’t find Mike Tyson saying, ‘Sure, there’s lots of guys who could beat me.’ You’ve got to slog, man. I’ve slogged my way up from the suburbs of Liverpool, and I am not about to put all that down.”

Nor is he about to let all that go forgotten. With the key Beatles lawsuits settled, he’s keen to go ahead with the long-discussed authorized Beatles film biography, The Long and Winding Road, although the project hit an early snag in terms of finding a director. McCartney mistakenly attempted to solicit interest from top screen talent by sending form letters outlining the project to the likes of Steven Spielberg, Ridley Scott and Michael Apted. “George [Harrison], who’s in the film business, went, ‘Major no-no, man, we shouldn’t have done that.’ And he should have stopped me. It was a mistake.”

Yet having willingly reawakened the Beatlemania beast with his current show, Paul McCartney enters the Nineties with a new variation on his old Seventies dilemma: How do you follow an act like the Beatles — again? He talks of making a new album with his touring band, and he’s halfway through a major orchestral and choral piece, written with British conductor Carl Davis, to be debuted during the 150th-anniversary celebrations of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic next year. More important, though, he’s come to realize that you don’t follow an act like the Beatles. You learn to live with it, and learn from it.

“I’ve already done the thing where you go out and shun the Beatles,” says McCartney. “That was Wings. Now I’ve done this whole thing. I recognize that I’m a composer and that those Beatles songs are a part of my material.

“The only alternative is that I turn my back on it forever, never do ‘Hey Jude’ again — and I think it’s a damn good song,” he says before heading out onstage, where he’ll play it again for a grateful crowd. “It would really be a pity if I don’t do it. Because someone else will.”

Last updated on February 3, 2022

Contribute!

Have you spotted an error on the page? Do you want to suggest new content? Or do you simply want to leave a comment ? Please use the form below!