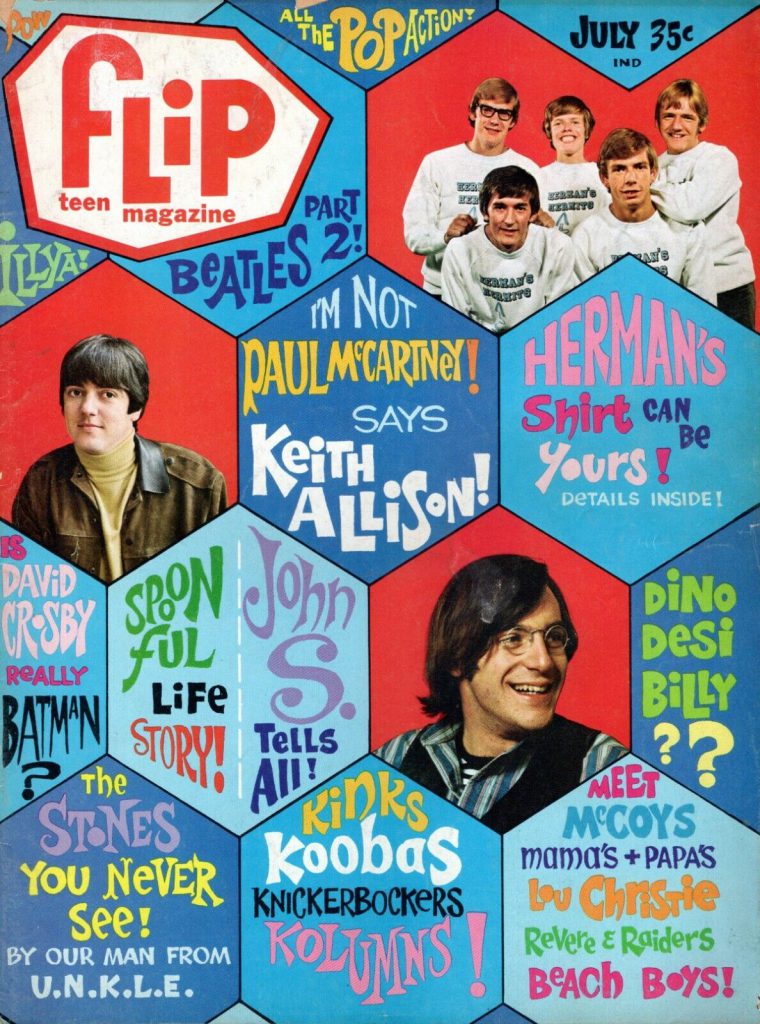

July 1966

Interview for Flip Teen Magazine

Press interview • Interview of The Beatles

Last updated on August 25, 2025

July 1966

Press interview • Interview of The Beatles

Last updated on August 25, 2025

Previous interview Jun 29, 1966 • The Beatles interview for NTV Channel 4

Concert Jul 01, 1966 • Japan • Tokyo • 2pm show

Concert Jul 01, 1966 • Japan • Tokyo • 6:30pm show

Interview July 1966 • The Beatles interview for Flip Teen Magazine

Concert Jul 02, 1966 • Japan • Tokyo • 2pm show

Concert Jul 02, 1966 • Japan • Tokyo • 6:30pm show

Next interview Jul 03, 1966 • Press conference in Manilla

John Lennon and Paul McCartney speak up!

May 1966 • From Flip Teen Magazine

This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

In 1966, Flip Teen Magazine published a two-part interview of Paul McCartney and John Lennon. The first part was published in the May 1966 edition and the second part in the July 1966 edition.

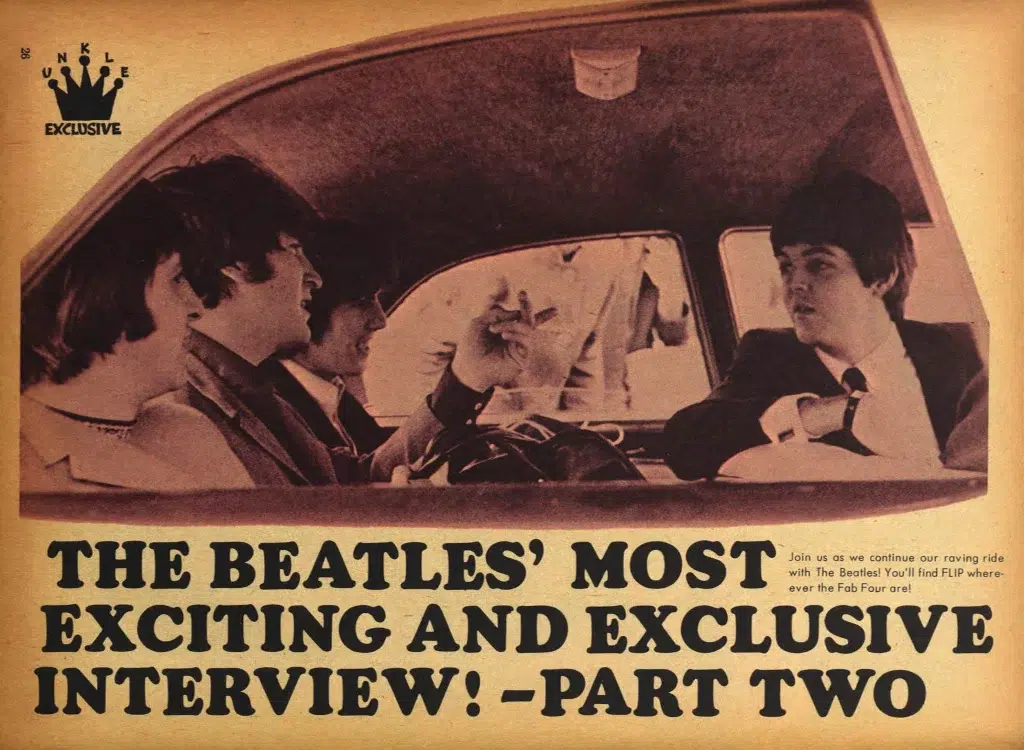

The most written-about people in the world must be Lennon and McCartney. But what do the Beatles think about the journalists who write about them? This subject of conversation arose during the afternoon I spent with them in their dressing room at the Manchester TV studio.

John offered a filter tip to top DJ Jimmy Savile, who had wandered in for a chat but declined and lit one of his famous 18-inch cigars after mentioning that George had previously requested he not do so. “That was George and not me,” said John. “You go ahead.”

I introduced the subject of reporters, and Paul rocked back on his chair with an intense look of concentration on his face. He was apparently trying to remember what one looked like.

“Yes, reporters,” he said reflectively. “You know we can always spot the journalists who understand what we are saying. In a crowded press reception there is always one guy writing down what none of the others have bothered to listen to. Those are the ones we dig.

“When you get as well known as we are now, people tend to make up things about you for the sake of stories. That’s not too bad as long as the stories are harmless and not adverse.

“We remember the people who helped us in the early days when we needed the publicity — the ones who didn’t jump on the bandwagon but helped to get us rolling naturally have our gratitude. We used to be knocked out back in the Cavern Club days if we got a couple of lines in the New Musical Express. It meant a lot to us then.”

John indicated the only other journalist present in the dressing room.

“Take Tom here,” he said. “Tom has probably spent more time with us than any other journalist in the world. He works for the Daily Worker. He’s a friend of long standing, and even if we don’t share his views we find his company interesting and agreeable.

“It has always been a part of our policy to be polite to the press. Reporters expect us to be polite — we’ve never taken the big-time line. Dylan has a different attitude. He has no time for stupid questions and is a sensitive, intelligent man. I respect that and him. His way is not to go out of his way. We do.”

“Sometimes I lose my temper, like the other day when a reporter from Liverpool came bustling up and demanded what I was doing to help save the Cavern from closing. ‘What are you doing to help the club that made you?’ he said. I told him straight that I believe we made the Cavern and the Cavern never made us.”

Paul made the observation that journalists in America and Britain differ widely in their attitude and while a number of Americans seem preoccupied with questions like ‘Do you Believe in God’ the British almost expect you to think up your own questions.

What kind of image would Paul report for the Beatles?

“You can only report the facts if you are honest,” said Paul. “The difficulty comes about when everything is put under a magnifying glass, and now if Ringo says ‘I’m going to the toilet’ some one will report it.”

As a writer himself John expressed surprise that people were shocked over the use of strong words.

“Someone actually sent me back a copy of ‘Spaniard In The Works’ because they claimed it contained bad language,” said John. “I kept it.”

The conversation was turned by Jimmy to tv productions of pop shows. I put forward the premise that there was a fortune waiting for someone who could think up a new way of presenting pop. Something to bring back the excitement of the “Oh Boy” shows produced by Jack Good.

“I’m not so sure,” said Paul. “When you look that far back you always tend to remember the good points. It’s like the people who compare the old sportsmen with the new. The older always looks better in retrospect. People will say the same about ‘Ready Steady Go’ in a few years time.”

John said that the most exciting programme they had seen for weeks was a discussion over Rhodesia between Quentein Hogg and Canon Collins.

“When two interesting conversationalists get on the screen we’re glued to the box,” grinned Paul. “Nothing is as exciting as a good spontaneous debate.”

At this juncture John had to go before the cameras and began to pull at his fringe.

“Y’know I keep having rows with Cyn about cutting my hair,” smiled John. “She always cuts it just that little bit too short. There’s a girl who lives locally who comes over to cut it occasionally but she is a friend and you just can’t keep trading on friendship.”

Paul patted his stomach after having eaten a hearty meal and observed he needed some exercise.

“Never did like sport,” said John, “Not even at school — I played football once and hated it. Still never mind all the great artists had physical disabilities, there was Byron with gout — Beethoven who was deaf and Shelley who drowned.”

“Was that a disability,” asked Paul innocently.

“It was after he drowned,” returned John.

“What about Coleridge,” asked Paul, “He wrote under the influence of opium.”

“An incentive, not a disability,” corrected John.

The question of symbolism then arose and Paul bought up the subject of what certain songs mean with suggestive lyrics.

“They said that ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ was about a junky,” said Paul. “Personally I think you can put any interpretation you like on it but when someone suggests that ‘Can’t Be Me Love’ is about a prostitute, that’s going too far.”

“Puff the Magic dragon is supposed to be about junkies,” said John.

“How about Jack and Jill?” asked Paul.

On a final note, I asked John what he thought he would be doing in five years time.

“If I thought I had to spend the rest of my life being pointed and stared at I’d give up now,” said John. “It’s only the thought that one day I’m going to be able to lead a normal life that keeps me going.”

“You just don’t think about,” said Paul. “We know it has to end one day but so does everything. You just take it as it comes—I’ll probably manage Brian Epstein.”

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.