Sunday, May 12, 2013

Interview for Mail On Sunday

It was a great love affair. But nobody's perfect

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Sunday, May 12, 2013

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Previous interview May 2013 • Paul McCartney interview for Q Magazine

Article May 07, 2013 • Paul McCartney rests at Txai Resort

Concert May 09, 2013 • Brazil • Fortaleza

Interview May 12, 2013 • Paul McCartney interview for Mail On Sunday

Article May 14, 2013 • Paul McCartney gives a masterclass at LIPA

Article May 15, 2013 • "Rockshow" theatrical release

Next interview June 2013 • Paul McCartney interview for MOJO

AlbumThis interview was made to promote the "Wings Over America - Archive Collection" Official live.

From me to you: Paul McCartney in his own words

May 12, 2008 • From Mail On Sunday

The interview below has been reproduced from this page. This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

Read interview on Mail On Sunday

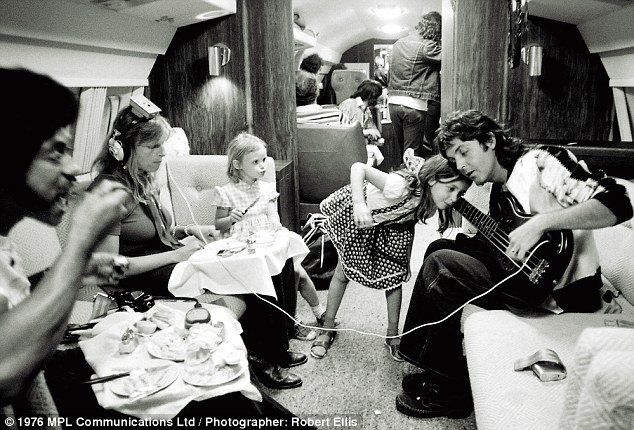

The photograph above was taken during the summer of 1976 and perfectly illustrates how being a member of the McCartney family must have been, in some ways, completely normal, and at the same time, utterly surreal.

In it, Linda and four-year-old Stella are settling down to dinner in a lounge, the former perched on a sofa while balancing a tray on her lap.

Across from them, Paul sits playing a bass guitar as Mary, only six, leans in to listen. It appears to be a fairly typical cosy, slightly boho picture. Except for the fact that it finds the McCartneys aboard their private jet, high in the skies above America.

‘That became normal for us,’ Paul tells me. ‘In our minds, we were giving the kids a normal upbringing. While at the same time we knew it was not.’

McCartney is on candid form today as he talks for the first time, and often movingly, about the momentous tour with Linda and their children that saved him from his deep post-Beatles depression.

He recalls the effect vicious criticism aimed at Linda, when she joined Wings, had on their family life, laughs as he shares vivid memories of wild adventures on the road with their young children as the McCartneys juggled family life with the chaos of touring the biggest stadiums in the world with a group of hedonistic musicians.

‘At the time we didn’t realise that that was quite strange,’ he says. ‘But actually, looking back at some photos, I do think, God, what were we on? But that was just the way we did it.’

Throughout the 1970s, the McCartneys were a travelling family, accompanying Paul everywhere as he carved out his post-Beatles career with Wings, whose membership included Linda on keyboards.

When back in England, the children attended local state schools near their home in Sussex (Paul and Linda being determinedly anti private education), though they often had to put up with mickey-taking from classmates about their odd, itinerant lifestyle.

‘Mary’s friends used to call her a “hippy commune kid”,’ Paul remembers.

‘It was those kind of days, though. I mean, it wasn’t really that far out. It was just kind of a question of everyone mucking in. We were more like gypsies than anything else. This family was going to move around…’

If McCartney in the 1970s managed to make balancing family and touring life look somehow effortless, he admits that it wasn’t always the case.

The pressures heaped on the married couple sometimes strained their relationship, causing them to bicker and argue, particularly if, while on the road, one of the children got sick.

‘Yeah, that would be the worst thing, if we were away and one of the kids was ill,’ Paul admits.

‘But life causes arguments and there were plenty of reasons for that. I don’t think having the kids on tour was particularly stressful. I think just people living together can be stressful. You know, it was a great love affair, but nobody’s perfect.’

Particularly in later years, Linda privately tired of being in Wings and on the road. But while she would reveal these feelings to others, Paul says that she kept these frustrations hidden from him.

She never said to you: ‘I’ve had enough’?

‘Uh, no,’ McCartney says. ‘I think it’s quite possible she thought that. She might have confided that to a couple of her mates, but we never really got into it.’

As McCartney talks to me today, it is nearly 15 years since Linda’s death from breast cancer in 1998 – which understandably devastated him – and 32 years after the end of Wings.

In spite of the fact that he turned 70 in June 2012, recent years have found him creatively re-energised, the past 12 months alone seeing him top the bill at both the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee concert and the opening ceremony of the Olympics, before walking away at the start of 2013 with a Grammy for his jazz standards album, Kisses On The Bottom.

But while obviously best known as a Beatle, McCartney can sometimes be taken aback by the impact other aspects of his career have had on younger individuals.

He tells me about an acquaintance of his, a former Olympic swimmer, who was dying to know which song McCartney was going to perform at the UK opening ceremony. Paul told him he wanted to keep it as a surprise.

The next time the singer bumped into the swimmer, he was a touch amazed to hear the athlete say that, while he loved Hey Jude, he was slightly disappointed that he didn’t play his favourite, Wings’ 1976 hit, Silly Love Songs.

‘Suddenly,’ McCartney marvels, ‘you realise it’s an age thing.’

McCartney clearly enjoys hearing compliments about Wings, not least since the 1970s were one long struggle for him.

Emerging from the wreck of The Beatles, he no longer had the protective shield of the Fab Four, nor could he count on instant adulation for his work.

In fact, the opposite was true. He found his motives and music constantly questioned and then came under fierce attack for having the audacity to make his non-musician wife a member of the band.

Paul first met Linda, an American divorcee and already a renowned rock photographer, in 1967, at the Bag O’Nails nightclub in London’s Soho.

‘There was an immediate attraction between us,’ he recalls. ‘It’s so corny, but I told the kids later that had it not been for that moment, none of them would be here.’

To Paul, Linda seemed altogether grown-up and womanly, in contrast to the giggly girls who tended to flock around The Beatles.

‘She had a five-year-old child,’ he points out, referring to his adopted daughter, Heather.

‘I was genuinely impressed by the way she handled herself in life.’

The couple married in March 1969, though the subsequent period proved a troubling one for McCartney, who suffered an acute personal crisis during the final, messy days of The Beatles.

Retreating to his High Park farm on the Kintyre peninsula in Scotland, Paul found it hard to get out of bed in the mornings and was drinking heavily.

In the end, he was pulled out of this depressive hole by his new wife.

‘Linda saved me,’ he admits. ‘And it was all done in a sort of domestic setting.’

In deciding to put together another band and make his return to live performance, Paul turned to Linda first, even though she wasn’t a musician. The couple were lying in bed one night in 1971 when he first broached the idea.

‘How it started,’ he remembers, ‘was I said: “Just imagine, y’know, we’re up on the stage and a curtain opens and there’s an audience. How would you feel about that?” And she thought about it for a moment and she said: “I think I’d quite like it.” And I said: “Well OK, that’s enough to start with. We can build on that.’’’

This was easier said than done, however. In the first line-up of Wings, Linda struggled to keep up on a musical level.

When in 1972, Paul decided that the newly formed band should set out – with kids and dogs in tow – on a UK tour of universities, turning up unannounced at student unions and asking to play impromptu shows.

Wings were so laid-back, they didn’t even book B&Bs until the day of the show, Paul and Linda often fashioning a cot in their room for the baby Stella, using an opened drawer.

‘We’d put blankets and sheets in it and improvise, and there you had a little baby cot.’

Throughout this tour, the musical teething problems they experienced were sometimes far worse than anticipated.

At one key gig at Leeds Town Hall, Linda froze onstage, paralysed by nerves, forgetting the chords to proto-animal-rights ballad Wild Life, which she was supposed to play to introduce the song.

Paul immediately rushed across the stage to her rescue, only to find that he too had forgotten the chords. The audience began to laugh nervously.

‘It was hilarious really, Paul remembers, ‘because I started it, ‘1-2-3’. I just looked around at Linda and there were no chords coming out and the audience thought, “This is good… this is a little joke they’ve got going.” So I said ‘1-2-3’ again and nothing came. Then I went over and it looked more like a joke – like a great big set-up thing. The joke was then I forgot the chords and I thought, Oh my God. So for a moment there was panic.’

Eventually, Linda somehow remembered the simple keyboard riff and the band joined in, their hearts racing.

‘I would say to her: “Everyone gets nerves, you know, particularly if you haven’t done it much,”’ McCartney recalls.

‘Anyway, she got over it, the more confident she got with her music. Onstage, she became the cheerleader. She had so much spirit, she became the core of the band.’

Nevertheless, Linda had to endure much in the way of vicious criticism from journalists, which McCartney nonchalantly insisted at the time was ‘like water off a duck’s back’.

But surely some of it must have hurt?

‘Well, it was like oil off a duck’s back,’ he laughs. ‘Bit harder to shift.’

At the time, many writers, and even fans, were scratching their heads in bewilderment wondering why the former Beatle was so keen to have his wife in his new band.

Then, at one point in the 1970s, the singer perhaps revealingly admitted that, taking uncertain steps in the long shadow cast by his former group, he needed Linda there ‘for my confidence’.

Today, however, he refutes this.

‘That’s not really true,’ he insists. ‘The thing is, if I’d needed someone there for my confidence, I would have got someone like Eric Clapton. So then I’d have more confidence, because I know he knows how to do it and I know how to do it. So it wasn’t so much that; it was more just Linda and I wanting to be together. I realised that if I was going to get a band together, one of the possibilities was that she would be in it. The other possibility was that she would come along with the band. But the first option, of being in it, sort of tickled us.’

More than anything, McCartney says, he saw Wings as an ‘experiment’. Having toyed with the idea of putting together a supergroup containing other famous names, the star decided to go back to square one with a band of virtual unknowns, including – at least in a musical sense – Linda.

‘I like the idea of raw talent,’ he explains. ‘We were going to do what all bands basically had done, which was start from nothing. When we started with The Beatles, we didn’t really know anything – we were fresh out of Hamburg with a few songs under our belt and we had to learn that fame game. So I liked the idea we’d all learn it together.’

Early Wings tours continued to be highly unorthodox. Their first European jaunt in 1972, for instance, found them travelling from show to show in an open-topped double-decker bus painted in psychedelic colours.

But the lumbering vehicle’s top speed was an unimpressive 38mph, resulting in promoters sometimes being forced to meet the band en route if it seemed they might be in danger of missing the gig.

This, ultimately, only added to the sense of adventure.

‘We were,’ says McCartney, proudly, ‘a bunch of nutters on the road.’

Still, a self-imposed rule in the first years of Wings, not to perform any songs from his Beatles catalogue, was challenging for him, particularly when his initial output following the breakup of his former group was decidedly patchy.

For every great single such as the beautifully dreamy Another Day or the thrilling, episodic Bond theme Live And Let Die, there was the baffling soft-rock nursery rhyme Mary Had A Little Lamb and the lightweight protest song Give Ireland Back To The Irish.

‘I wanted to grow Wings from seed,’ he explains. ‘And that was what we ended up doing. However, this meant that, you know, if you had a bad spring and you didn’t get enough rain or enough sunshine…’

You’d find you had a poor song harvest?

‘Yeah,’ he laughs. ‘And we had some pretty bad weather in the early days.’

After all of the initial struggles, come 1976, McCartney felt sufficiently emboldened by the progress of Wings to return to the U.S. for a major concert tour, ten whole years after The Beatles had quit live performance.

The Wings Over America jaunt was a hugely ambitious affair, taking in enormous arena gigs and a sold-out show at Seattle’s Kingdome stadium, where the group played for 67,000 fans, beating the attendance record previously held by The Beatles for their landmark Shea Stadium show in New York in 1965.

In America, McCartney’s reappearance onstage was treated by many as some kind of second coming.

At Wings’ first U.S. show, on May 3, 1976, at the Tarrant County Convention Center in Fort Worth, Texas, the star got a 15-minute standing ovation before he’d played a note.

But it was, he admits: ‘Nerve-racking. This was big-time American media: The Beatle returns. What’s he going to be like? You want to throw up. But you get on there and you suddenly see, these are your people, this is OK. You’re home.’

Following the modest early days of Wings, McCartney had stepped back into the full glare of the media spotlight.

‘Yeah, it was interesting,’ he says. ‘Because we started so small, it was like I wasn’t famous. But then, suddenly all that fame came back. You were suddenly on prime-time news.’

Even with this level of tour, there was never any question of the McCartney kids being dumped on to nannies or sent away to boarding school.

‘That’s right, and we even got slagged for that,’ Paul says. ‘I remember someone saying: “Oh, they’re dragging their kids around the world.” And our answer for that was to say: “Yeah, look, the thing is, number one, we love ’em. Number two, what are we gonna do? We’re gonna be in Australia and a nanny’s gonna ring up and say: ‘Ooh, your kid’s got a fever of 105.’” We would wanna be there, so that was it.’

Wherever they were in the world, the McCartneys employed tutors for the kids.

‘We’d get them to talk to the school first and find out what subjects they were going to cover,’ Paul explains. ‘We kind of kept up. The kids tell me now they didn’t really keep up. They did inevitably sort of fall behind a bit. They would moan when they had to go to a tutor instead of going on the beach in Brazil. But, hey, if you’re talking geography, they got an A plus.’

‘Y’know, nobody’s saying it was perfect,’ he adds. ‘But is life really perfect when you sit in an office all day and then you go home and see your kids at night? I’m not sure that’s any better.’

Aboard the customised British Aircraft Corporation 1-11 jet that flew the McCartneys and band from gig to gig, the children particularly loved the mini-disco situated in the rear of the plane, with its fluorescent lights, luminous stars and state-of-the-art sound system.

Elsewhere, in spite of the fact that some members of the group displayed distinctly hedonistic tendencies – not least wildcard Scottish guitarist Jimmy McCulloch, who died three years later in 1979 as a result of his various habits – McCartney says that it wasn’t difficult to maintain a reasonable distance between his children and the harder-living rock and rollers.

‘Well, the nice thing about anyone who’s likely to get a bit crazy is they’re normally not gonna do it around the kids,’ he stresses.

‘I’ve known some of the most legendary madmen in rock ’n’ roll, but, when they’re hanging out with me and the kids, they’re unbelievable gentlemen. Someone like Keith Moon was the world’s greatest gentleman. So this is what happened – anyone who was likely to get crazy, it would be on their own time, in a hotel room and somewhere where the kids weren’t. They were very respectful and the kids never really saw any kind of hedonistic behaviour.’

As the Wings Over America tour progressed, the almost Beatlemania-like crowd hysteria began to intensify and Paul’s returned star power drew celebrities from all corners.

Backstage at Madison Square Garden in New York, the McCartneys were visited by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and her children, John Junior and Caroline Kennedy.

At an extravagant end-of-tour party at comedian Harold Lloyd’s former estate in Los Angeles, A-list Hollywood guests included Henry Fonda, Steve McQueen and Tony Curtis, along with major musical names including The Jacksons and Bob Dylan.

In the final reckoning, Wings Over America was a triumph. After a bumpy start to the 1970s, Paul McCartney was now as successful in his own right as he had been as a Beatle.

‘I sometimes wonder if it was crazy after The Beatles to do the entire thing again. To cook another three-course meal starting from scratch. And at times it looked like a crazy decision but we finally proved we could be a really cool band – play to American audiences in the same way The Beatles had and have the same impact, in a different way. It was a buzz. A huge buzz.’

In the end, McCartney has nothing but positive memories of his life with Linda and the kids and Wings.

‘Y’know, I like to see the good in everything,’ he concludes. ‘The memory overall of the Seventies was that it was difficult, but the fact it worked was really rewarding. So it’s great to see Linda up there, rocking, looking great. ’Cause you sort of think, God, the s*** she endured, bless her. And here we are on stage, and it all worked out.’

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.