Interview location: Apple offices, 3 Savile Row • London • UK

This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

Paul McCartney had been deeply involved in the activities of Apple Corps since its inception in 1967, often taking a hands-on role in its creative and business ventures. However, following the appointment of Allen Klein as business manager for John Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr in May 1969 — a move Paul opposed—his presence at Apple diminished noticeably. After John privately announced his decision to leave The Beatles in September of that year, Paul withdrew further and was rarely seen at Apple’s Savile Row headquarters.

This article features comments from John Lennon, Derek Taylor, George Harrison and Allen Klein.

Paul is rarely seen there nowadays. Lennon’s and Harrison’s names are the only ones given on the company notepaper as directors. After a reign by McCartney, John is also reinstated in the world’s mind as the senior partner of the four.

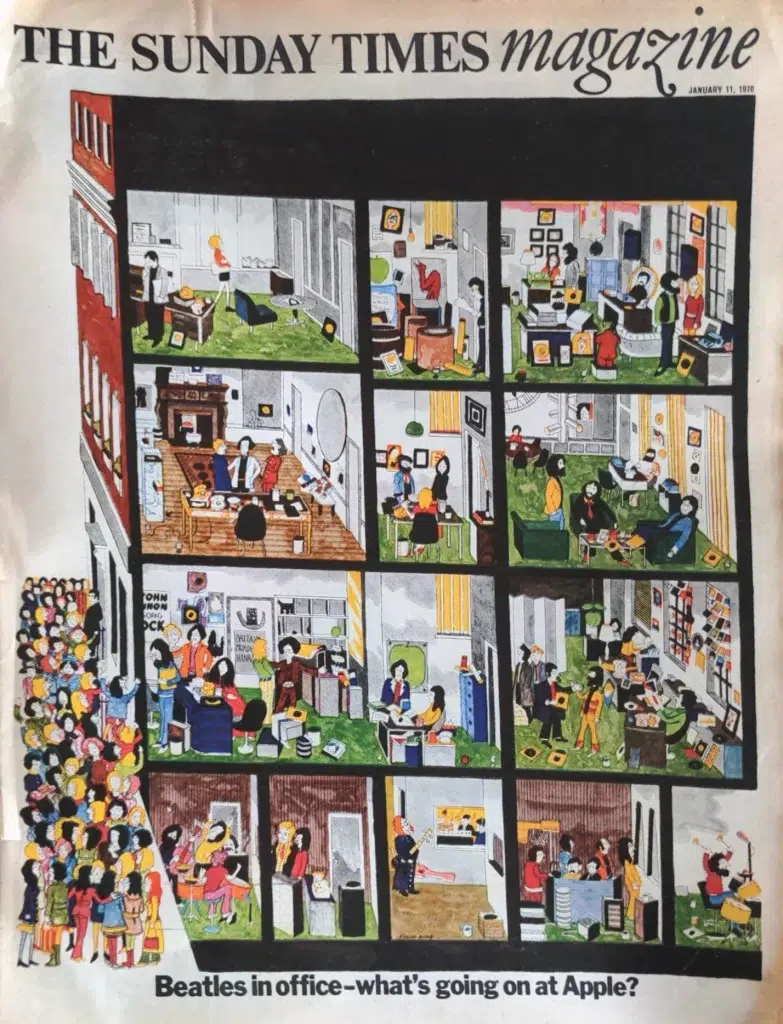

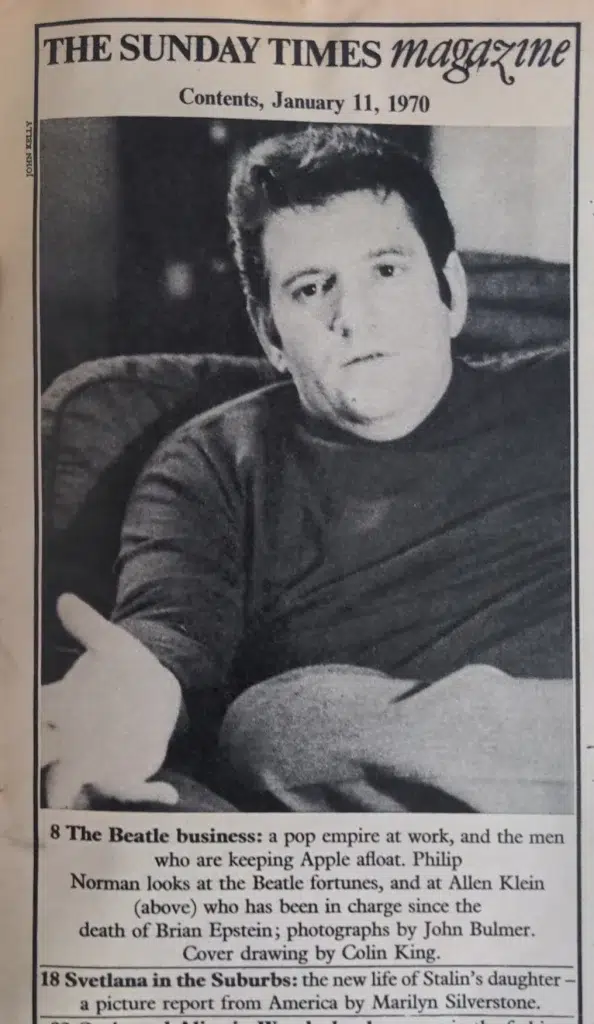

What has happened since Allen Klein gained control at Apple Inc., the Beatles’ business run from Savile Row (below)? Does it make money, or is it still as rich a whim as John and Yoko’s fondness for chocolate cake? By Philip Norman, photographs by John Bulmer

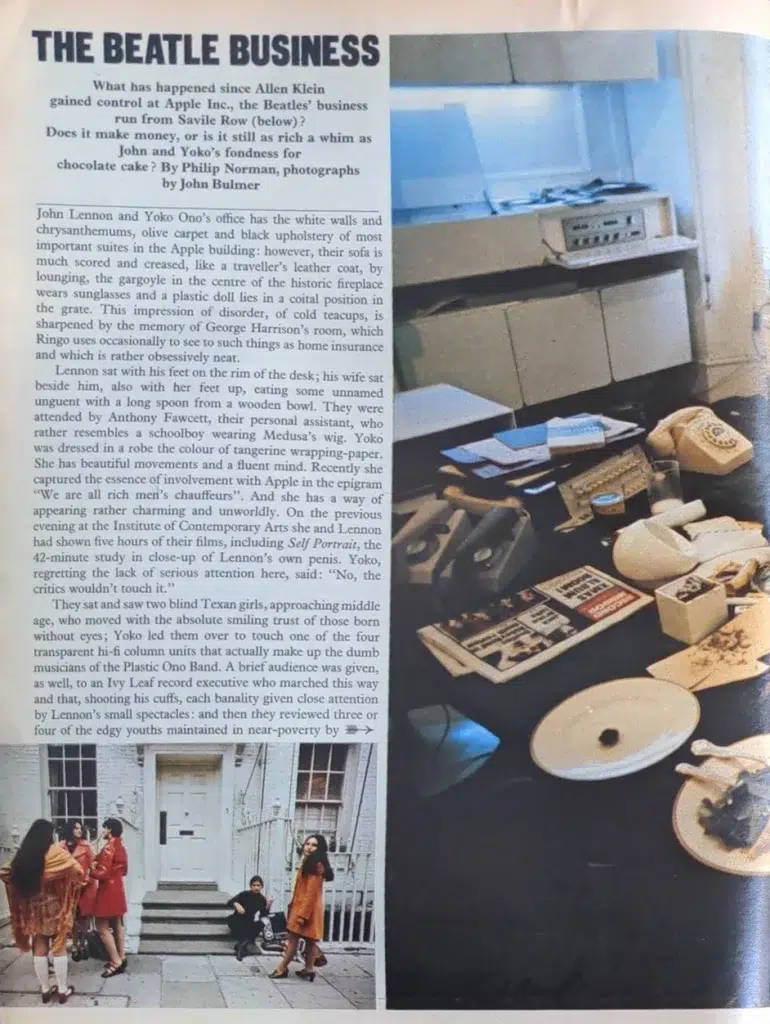

John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s office has the white walls and chrysanthemums, olive carpet and black upholstery of most important suites in the Apple building: however, their sofa is much scored and creased, like a traveller’s leather coat, by lounging, the gargoyle in the centre of the historic fireplace wears sunglasses and a plastic doll lies in a coital position in the grate. This impression of disorder, of cold teacups, is sharpened by the memory of George Harrison’s room, which Ringo uses occasionally to see to such things as home insurance and which is rather obsessively neat.

Lennon sat with his feet on the rim of the desk; his wife sat beside him, also with her feet up, eating some unnamed unguent with a long spoon from a wooden bowl. They were attended by Anthony Fawcett, their personal assistant, who rather resembles a schoolboy wearing Medusa’s wig. Yoko was dressed in a robe the colour of tangerine wrapping-paper. She has beautiful movements and a fluent mind. Recently she captured the essence of involvement with Apple in the epigram “We are all rich men’s chauffeurs”. And she has a way of appearing rather charming and unworldly. On the previous evening at the Institute of Contemporary Arts she and Lennon had shown five hours of their films, including Self Portrait, the 42-minute study in close-up of Lennon’s own penis. Yoko, regretting the lack of serious attention here, said: “No, the critics wouldn’t touch it.”

They sat and saw two blind Texan girls, approaching middle age, who moved with the absolute smiling trust of those born without eyes; Yoko led them over to touch one of those transparent hi-fi column units that actually make up the dumb musicians of the Plastic Ono Band. A brief audience was given, as well, to an Ivy Leaf record executive who marched this way and that, shooting his cuffs, each banality given close attention by Lennon’s small spectacles: and then in reverie they saw four of the edgy youths maintained in near-poverty by the record trade press. These had been sitting upstairs in the Press department as if waiting to see the dentist; queuing next to an enamel tray of water into which toy birds dip their beaks in perpetual motion as the room’s light show casts rainbow-coloured spermatozoa over the reporters’ nervous faces.

Why had Lennon shown this film of his partial and full erection? It was simply a self-portrait, he replied. How was his and Yoko’s Peace movement developing? “It’s something if you can just convince your own Dad.” He offered to draw a poster to be given away to the best reader’s suggestion for seeking peace. He was consistently polite and free with his cigarettes. He has, it is agreed, mellowed wonderfully since his marriage to Yoko — “He could be a real bastard before,” one colleague said; and he is second only to Paul McCartney in his pursuit of good public relations — more so in respect of Apple, since Paul is rarely seen there nowadays. Lennon’s and Harrison’s names are the only ones given on the company notepaper as directors. After a reign by McCartney, John is also reinstated in the world’s mind as the senior partner of the four.

At the same time he continues, with his wife, to develop their bizarre mixture of art and vaudeville; a collection of whimsy, ancient rock and roll, both splendid and dreadfully tedious film ideas and a great deal of sheer microphone noise. What they really want is to get everybody to join in. “We’re all frozen jellies,” Lennon says. “It just needs someone to turn off the fridge.” (He, too, has the gift of epigram about Apple. “The circus has left town but we still own the site.”) The following weekend he and Yoko flew quite unexpectedly to sing at a concert in Toronto; their film The Two Virgins was practically scheduled to be shown by United Artists with Chaplin’s The Circus; they were also planning to make a picture based on the A.6 murderer, James Hanratty. Their partnership has only just started, since each has years of bottled-up ideas to contribute to it (Yoko, indeed, has about 15 years) and both give the impression they would rather work at home on this than at Apple.

Compared with its few recording properties – Jackie Lomax, Billy Preston, White Trash, a Scots group who float about the house like the cast of a junior Pirates of Penzance – John and Yoko’s record sales have been enormous. Give Peace a Chance and the Ballad of John and Yoko each fell not far short of those from Mary Hopkin’s Those Were the Days; but still the company seems to make little of them as a collaboration. “I don’t feel hostile about it, no,” Lennon said. “But sometimes I think they’d rather not acknowledge us and wouldn’t mention us at all unless I’m there to catch the fellow sending out the bloody promotionals.”

George Harrison’s tidy office is on the first floor; Lennon’s is off the ground floor entrance; he and Yoko are therefore the most vulnerable – to the daily cluster of admirers on the doorstep and to everyone else. For a long time he was the only Beatle willing to put himself out, to travel to appear on a stage; for that reason he is the most spat-upon. Some employees refer to him, affectionately, as the Leper. He causes some of the largest problems to the Apple press department; serious and exhausting problems largely unperceived by the idlers who pass through it. For instance, Derek Taylor, the publicist, has for months been trying to get him an American visa. A lawyer said on the telephone that Lennon must state a reason for the visit: the State Department would like this to be purely business but the Department of Justice preferred Lennon to say he intended to visit a mental health conference.

“The lawyer tells me that as an American he is ashamed of his country’s behaviour,” Derek Taylor said. “They phrase it that John is guilty of a crime of moral turpitude. You actually get a man at Immigration saying you are guilty of a crime of moral turpitude. John just says ‘turpentine’—wry Liverpool humour. But what it really means is they don’t want him to have a bed-in like he did in Montreal. Why does he want to go to America? He wants to go to America to go to America—to see a few friends. That’s what we’re dealing with here sometimes; wicked, evil people.”

The Apple offices are contained in a white building of character that cost some £500,000 in Savile Row, Mayfair. Its proximity to the tailoring establishments and to the Burlington Arcade, where ties and foulard scarves are hung up like a gamekeeper’s kill of jays, only serves to remind one that the Beatles themselves are no longer shirt kings. In fact they are all rather badly dressed; even Paul McCartney, who spends a lot on having suits made to look inconspicuous and loose-fitting, like his father’s.

The interior of the house is far from opulent: there are graffiti scratched inside the lift, the olive carpet is loose from its stitching in places, the large oil painting of a pride of lions that hangs over the staircase is never illuminated; one senses endless and unheeded framed lines of golden discs. The slightly crammed character of most offices seems to underline the spirit of newly trimmed efficiency abroad in the place. Only in the room now occupied by Neil Aspinall, the Beatles’ former road manager, is there any size of baroque ceiling-work; and this used to be the Beatles’ own until each of them found his level in the enterprise.

Elsewhere there are a great many posters, loose sheets of paper and Apple symbols; great rallies of empty glasses, oddments of office furniture, lamps that do not match one another. The only magical elements are modish telephones and bleeps, an ice machine of unusual proportions and, in the basement, a practice-room to which occasional parties from the doorstep are taken; they run fingers over items of equipment with the speechless wonder of peasants at Lenin’s tomb.

The Apple business, its catalogue, has been ruthlessly sorted out since January by a man named Allen Klein, a New York Jewish accountant who, according to George Harrison, looks like Barney Rubble from The Flintstones. At Klein’s direction most of the dreams that Apple had at the beginning, such as the transistor radio inside the plastic fruit, have been cleared away. What is left is a business occupied by the functions of a Beatle that a Beatle understands best – composing, arranging, playing and recording and producing book and film documentaries of these activities. What is left is a house with a not unreasonable amount of staff in it, in slight trepidation of long conferences.

Apple, according to Klein, has one purpose now, realised through him.

“I want to make each one of the Beatles individually wealthy; wealthy enough to be able to say ‘FYM – F… You Money’!”

He was eating an afternoon breakfast in the coffee shop of the London Hilton. Close by, at Hyde Park Corner, a garrison of hippy squatters had been defying the police from an old mansion they were illegally occupying, fortified by a gift of records from Apple. Klein could not have been aware of this vestige of the pre-Klein Utopian spirit, since he had spent most of the previous day and night locked in conference with the Beatles over the revisions to their contract with EMI records, who at present distribute the Apple label.

Under the new terms they will receive 5s. 9d. per copy of each album sold and, after three years, 7s. Directed by the late Brian Epstein, the most they ever had was about 2s. 6d. per album: for a grand succession of works up to the Sergeant Pepper tour-de-force, they received 6d.

“He coulda’ had the world,” Klein said of Epstein, “but he was interested in his other artists. He was a bad businessman; but I don’t want to talk about a dead man.”

In view of the way Klein is disliked and feared and barred from some company (one of his Apple colleagues put him among the Undead), he appeared astonishingly direct and outgoing, rather a nice man. Yet his arrival at the beginning of 1969 to manage the Beatles in return for 20 per cent of their income was widely considered to be the final rabbit punch to an organisation that was already gloomy and unpopular and had made the Beatles, for the first time in their careers, unpopular.

Five divisions of Apple existed then, to promulgate electronics, boutiques and mail order as well as records, films and publishing; and Lennon was predicting that if everything continued to spend money at the same brisk rate, the Beatles would be penniless in six months.

“We’ve been giving away too much to the wrong people – like the deaf and the blind,” George Harrison added.

Lennon and Yoko were increasingly being turned into figures of fun and, on top of everything else, the Beatles themselves were called musically lame; their film Magical Mystery Tour was laughed at. Moods of this time went, inevitably, into their Abbey Road album then in preparation, and not a little irritation.

Klein, a man whose personal atmosphere is darkened habitually by huge argument, writs and litigation, already managed the Rolling Stones; in fact Mick Jagger was one of the first to suggest that he might assist the Beatles. Klein had dreams of annexing the Beatles as far back as 1964 when I Want to Hold Your Hand was top in America. Thwarted in this desire, he instead founded the fortunes of such British artists as Donovan, Herman’s Hermits, the Animals and the Dave Clark Five.

John Lennon was most in favour of engaging Klein, and Paul McCartney least. He was finally admitted with four things to do. The first was to reorganise Apple, which he performed by wholesale and eagle-sudden dismissals of big and small, and at the same time disengage the muddle of obligations and contracts left behind after Brian Epstein’s sudden death and negotiate the new deed with EMI records. He had to gain control for the Beatles or independence from the companies formed to absorb the treasures of the earliest Beatlemania — [MISSING THE END OF THE ARTICLE]

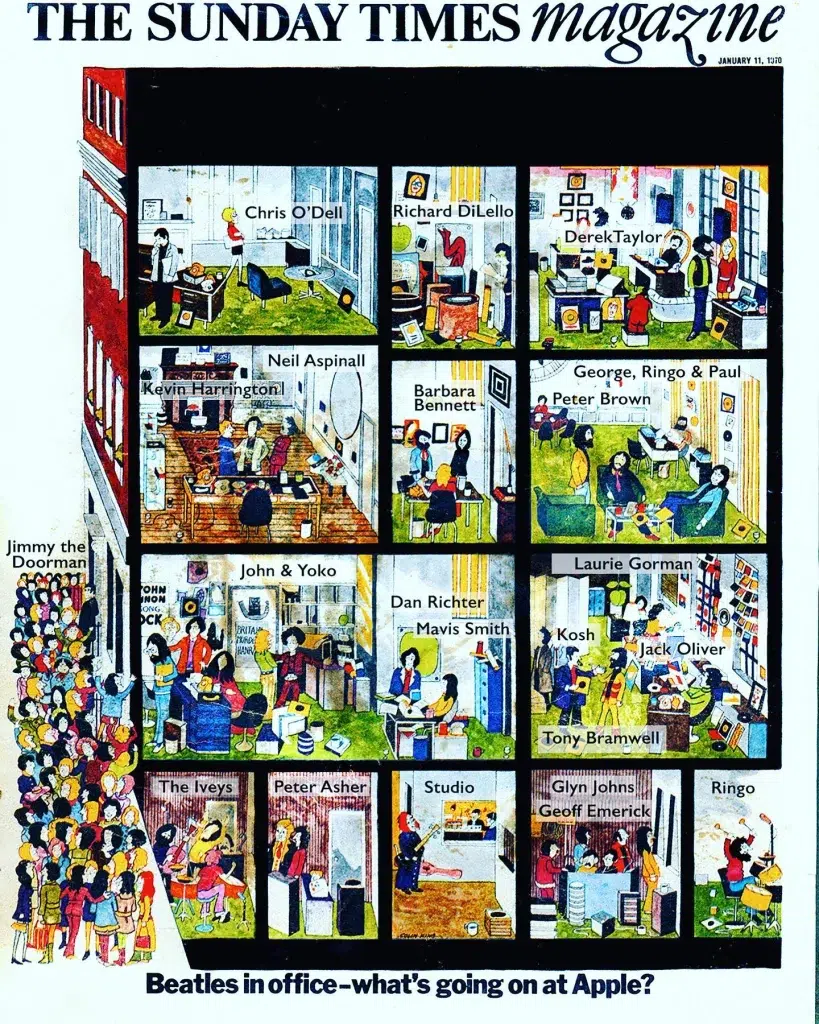

In 2023, John Kosh, who served as creative director of Apple Corps in late 1969 and into 1970, shared the cover of The Sunday Times Magazine that had originally featured Apple’s Savile Row headquarters. On this version, he added labels to identify the various Apple offices shown in the photograph, offering a clearer view of how the different departments were situated within the building.

The Sunday Times Magazine 1970! Beatles in Office – What’s Going On at Apple? We had some fun labeling the various office space with the talented cast of characters always buzzing throughout

John Kosh – From Facebook, June 4, 2023

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.