Sunday, September 2, 2018

Interview for The Sunday Times

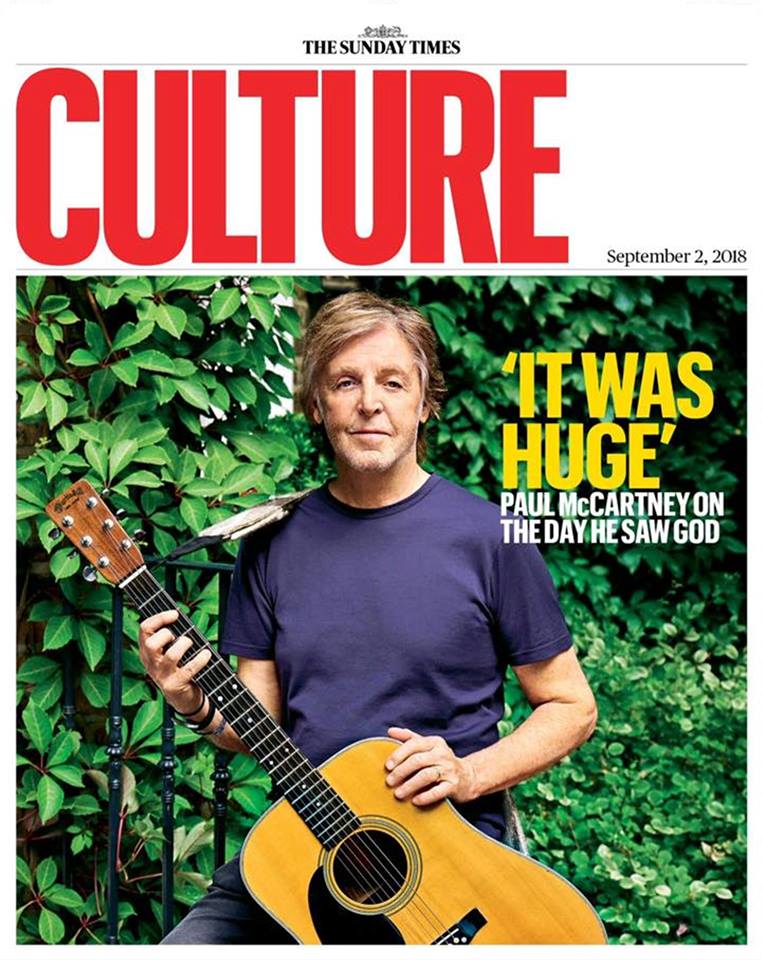

Paul McCartney interview: the Beatles star on seeing God, teaching Stormzy to play piano..

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Last updated on April 6, 2021

Sunday, September 2, 2018

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Last updated on April 6, 2021

Previous interview Aug 01, 2018 • Paul McCartney interview for paulmccartney.com

Article Aug 31, 2018 • "Freshen Up" tour US leg announced

Article Sep 01, 2018 • "Al Schmitt on the Record: The Magic Behind the Music" book published

Interview Sep 02, 2018 • Paul McCartney interview for The Sunday Times

Article Sep 03, 2018 • "Freshen Up" Japan leg announced

Interview Sep 03, 2018 • Paul McCartney interview for Sodajerker

AlbumThis interview was made to promote the "Egypt Station" Official album.

Officially appears on FourFiveSeconds

Officially appears on Rubber Soul (UK Mono)

Officially appears on I Don't Know / Come On To Me

Officially appears on Egypt Station

The interview below has been reproduced from this page. This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

Read interview on The Sunday Times

From paulmccartney.com, January 11, 2019

The promotional duties for the album release were getting into full swing and he had a succession of visitors to his studio in Sussex over a two-day period. They included a cover interview for Mojo magazine, Sunday Times Culture, a GQ cover story, an appearance for the CBS show 60 Minutes and chats with Radio X, BBC Radio 6 Music and the website DIY (the first interview from this campaign to appear).

Stuart Bell, Paul McCartney’s publicist

Whenever I go to Abbey Road, just the thought of how many creative moments happened there makes me want to sit and think… Ah, there’s John, doing Girl…

Paul McCartney

At 76, the singer is unstoppable. He is about to release a new album and has just played a two-hour private gig at Abbey Road. Off stage, he’s more vulnerable. And confessional: there was the day he got high and saw the Almighty, for starters. By Jonathan Dean

Paul McCartney played at Abbey Road Studios again a few weeks ago, and what a trip that was. He sang hits including We Can Work It Out and Drive My Car about the distance of three McCartneys away from his audience. This tiny gig was part show of the decade, part Madame Tussauds on tour. Johnny Depp stood next to Orlando Bloom, George Martin’s son Giles waved from a booth, and McCartney, on beaming form, carried on for almost two hours as everybody pinched themselves. Amy Schumer screeched and JJ Abrams swayed. Kylie Minogue spun Stella McCartney around the floor.

After a while — possibly when I spotted Nile Rodgers; possibly when McCartney serenaded his wife, Nancy; possibly when he banged out Lady Madonna on the actual piano he wrote the flipping song on — my mind boggled so much that my notes just ended up with outbursts including “STORMZY!”. Because the grime star was there, too, enjoying Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da.

Life goes on, somehow, after an afternoon like that, and the next morning, in his Soho Square office, McCartney was still basking in the joy of playing for family, fans and the famous, mostly invited by Stella. “Whenever I go to Abbey Road,” he says, “just the thought of how many creative moments happened there makes me want to sit and think.” He pauses. “‘Ah, there’s John, doing Girl…’

“Stormzy asked for advice,” he continues, anecdotes popping up all the time. “He’s looking to advance his music. As a rapper, I thought he’d have words down, but there was a piano, so I showed him basic stuff — how you get middle C, make a chord, a triad and, just by moving that, get D minor, E minor, F, G, A minor, and how that’s enough for anyone.” He took this in? “Think so.” McCartney starts humming, clicking his fingers. He’s buzzing. “That is exactly how we started.”

The music McCartney made with John, George and Ringo has reached its third generation, at least. The Beatles split almost 50 years ago, but their songs are still the sounds on the streets of this country and up in the sky, and everyone has their favourites. For me, by the Beatles, it is A Day in the Life and Norwegian Wood; by Wings, I also love Let Me Roll It. There is no way this music isn’t for ever, and, to show off at the age of 76, the most successful pop composer of all time is releasing a 17th solo studio album, Egypt Station. It will add to his 700m album sales.

The LP has a number of highlights and, from the pretty, acoustic Confidante to the seven-minute Despite Repeated Warnings, via the rock strut of Who Cares, it does what you want a McCartney album in 2018 to do: it includes five or six songs he can play at a concert that don’t feel like impostors taking the place of Love Me Do. The first single, I Don’t Know, features his best melody in years.

No wonder he seems relaxed when we sit down. He’s dressed in a loose shirt and sandals, a classic pensioner Brit in summer. If you had to age him, you’d go for 65. A desk to one side of the room is full of photos of his children and grandchildren, while his iPhone case is a custom-made family portrait. There are a lot of people on it. We sit on a sofa next to a jukebox and a guitar, surrounded by art. His eyes are wide and bright, and it’s hard not to think of the people he has seen and the memories that will vanish when he is gone.

Because, of course, McCartney won’t be with us for ever, and that will feel very weird indeed. “I say, in history, where Queen Elizabeth I had Walter Raleigh, Queen Elizabeth II had the Beatles,” he says, and many alive today can’t remember a time without our monarch and her moptops, both synonymous with Britain since the latter started their parade in her reign back in 1963.

“She is the glue,” McCartney says of the Queen, for whom he has essentially provided a soundtrack for all but a decade of her rule. In May, the singer received his latest title, Companion of Honour. What did you talk to her about this time? “You’re not supposed to say, so I’m going to be a good boy,” he says cheekily, clearly tempted to spill.

Did you teach her piano, like Stormzy? “No. Unfortunately there wasn’t a piano, or I’d have shown her middle C.” His fandom for our monarch goes back to her coronation. He was 10 and wrote an essay about her that won him two books as a prize. He fancied her back then, too. They have known each other for half a century.

There is a serenity in being in McCartney’s company. He exudes calm and humour, yet his soft voice cracks on occasion, too, revealing that, yes, he is human. Live, he feeds off the crowd, such as the young woman in a glittery dress pogoing to A Hard Day’s Night at the Abbey Road gig. Compared to the man on stage, though, sweating carnal energy from the opening riff, McCartney is humble in person. Indeed, in conversation, he is clearly a man in his eighth decade, with more history behind him than most. Maybe that is why he is comforting: it is always strange to find that someone this great is, like us idiots, flawed. “I’ve got so many lessons to learn,” he sings on I Don’t Know, which intrigues me, I tell him, not only because of his age, but because he is bloody Macca.

“Did you think, when you were a kid, that at some point you would have it all down?” he asks quietly, rhetorically. “That you would have sussed the whole thing out and wouldn’t have to think about new challenges? Well, I don’t find that to have been true. Life isn’t like that. It keeps throwing you a curveball. It keeps moving. It keeps it intriguing.

“Also, if you have children, you always learn lessons, because there’s no accepted way to bring them up. It’s the biggest ad lib of your life, as they tell you one thing, but your kid might not fit that mould. Throughout history, I can’t think of anyone who didn’t have some kind of insecurity.”

What is he insecure about? “General things. Is this song good? Is this the right way to bring up kids?” There is, I say, a misconception that being a pop star always brings happiness. “It brings its own problems,” he says. “Having said that, I have a very good life.” He pauses, knocks on a nearby wooden shelf. “But, in that very happy life, there are insecurities. I’ve never reached a point where I’ve just gone, ‘Sod it. I’m terrific. And you lot can do all the worrying.’”

I tell him I want to get deep. He nods. A few months ago, during a Carpool Karaoke session with James Corden in which the two men drove around Liverpool singing, Corden mentioned his grandfather, and how he would have loved to know that his grandson was in a car with a Beatle, had he still been with them. “He is,” McCartney replied quickly, and it was oddly beautiful, even spiritual. Corden cried.

What did he mean by those words? “As in, was it a religious moment?” McCartney asks. Exactly. “Not really. But, having lost both my parents and Linda, and having experienced people close to me dying, you often hear this from others when you say you’re missing a person so much. ‘Don’t worry,’ they say. ‘They’re here, looking down on you.’ And there’s part of you that thinks there is no proof of that. But there’s part of you that wants to believe it.”

His voice cracks. “So,” he continues, almost in a whisper, “I like to allow myself to think that happens, rather than stopping myself thinking of the possibility. I’ve grown to allow myself that. When Linda died… When you are grieving like that, you see little things, and you know you’re reading into it, but you don’t mind. You allow yourself to read into it. I was in the country once, and I saw a white squirrel. So, this was Linda, come back to give me a sign.” He gasps at the memory. “It was a great moment. It thrilled me. Goosebumps! Obviously, I have no proof it was her at all, but it was good for me to think that.”

In 1967, McCartney said of his bandmate Harrison: “I envy George, because he now has a great faith. He seems to have found what he’s been searching for.” When I ask if he is still envious, he says he’s never really been searching, and that, while his mum was Catholic and his dad Protestant, they weren’t a religious family. That has stuck with him. Jesus, he thinks, said a lot of great things and the Bible a lot of terrible ones, mostly about vengeance. So he cherry-picks from different religions to form his own belief.

“But I do think there is something higher,” he says, pretty much out of the blue. Like what? “No idea! But I sense that through experiences I’ve had. I once took a drug, DMT. There was the gallery owner Robert Fraser, me, a couple of others. We were immediately nailed to the sofa. And I saw God, this amazing towering thing, and I was humbled. And what I’m saying is, that moment didn’t turn my life around, but it was a clue.”

What did God look like? “It was huge. A massive wall that I couldn’t see the top of, and I was at the bottom. And anybody else would say it’s just the drug, the hallucination, but both Robert and I were, like, ‘Did you see that?’ We felt we had seen a higher thing.” He bursts out laughing. “I can just see the bloody headlines now: ‘I saw God!’”

Well, I didn’t expect him to get that deep. Still, the singer has, for decades, had a fascination with the beyond, never satisfied with doing anything simple since Rubber Soul. Time at an ashram, drugs, teaming up with Skype for the world’s first audio emojis, a cameo in Pirates of the Caribbean, Pure McCartney VR (“Never miss a piece of immersive content!”), working with Kanye West…

You are restless, I say. “Yes,” he replies, grinning. “You can’t put a word to it without sounding corny, but this journey… I like this continuing aspect of creativity.” He picks up his guitar. “Working with Kanye, for instance. I’m sitting around the Beverly Hills bungalow, going…” And at this point McCartney stares right at me, raises his eyebrows and launches into a slowed-down version of the riff from FourFiveSeconds, the song he wrote with West in 2014. I tap my feet.

“I originally thought we would sit down and” — he plays an upbeat melody, singing in an elaborate, bluesy pop style — “‘Well, today’s a good day!’ And he’d go, ‘Yes, it sure is.’ And I’d go, ‘Come on now, Kanye, we have gotta take a piss!’ Or whatever. But it turned out it wasn’t like that. He recorded with his iPhone and, months later, I got this…” He strums the finished, speeded-up riff and — quite the experience — does an impersonation of Rihanna, who sang on the track. “I didn’t even know we were connected to Rihanna!” he says, cackling. I’ve never felt so delighted to be a journalist.

The door to his office opens. “How’s another 10 minutes?” his PA says. “We want about five more hours!” McCartney replies, and she’s off, with him back to “the Kanye thing”, fascinated by his way of working — so much more than some contemporaries, who tediously dismiss hip-hop outright.

“When Mary was born,” he says, “we were in this clinic, feeling so cool about having this baby, Linda and I. She was our first together. And I saw a picture on the wall, Picasso’s The Old Guitarist. I wondered what chord he was playing, and I was telling Kanye this…” Still holding his instrument, he plays the two-finger chord. He whistles, strums, and it’s lovely, yet the tune eventually wound up remixed, opening West’s abrasive All Day. It’s some sonic shift, but how gripping this all was, and how bizarre it is to be serenaded by McCartney, across a low-slung coffee table, in an office he’s owned for years.

We move on to the state of the world. A song on Egypt Station, People Want Peace, could have fitted on the last couple of Beatles records or, more likely, an early Lennon effort, given its chanted, clapped choral refrain about peace. It is an agitated time now, though, and giving peace a chance barely seems to be on anyone’s agenda.

“Violence and arrogance are back,” McCartney says. “It’s like how fashion goes in cycles, how bell-bottoms came back. We were heading towards sense, but we are into the next pendulum swing now. That happens in life.” Does he think it will swing back? “I believe so, having seen it so many times.” He gestures out of the window to the square, full of office workers playing table tennis in the sun. “This square was filled with garbage in the 1970s, when everyone went on strike. Cemeteries were left to rot. We felt we were heading to Armageddon, but it cleaned up.”

When McCartney was a teenager, he didn’t know the system. He had no idea you were meant even to apply to university. Still, he wasn’t hugely academic. He is of the world, not an expert on it. The careers master said he only had qualifications to be a teacher. “Which is weird,” he laughs. “You’re crap, so teach other people to be crap!”

In a way, though, he has been teaching us all along: all the stuff that matters. “It’s never got to be like a job,” he says, grinning, of this oddest of careers. Still, cutely, he is staggered that he gets to do what he does. “I love it. You sit down and there’s a black hole you pull something out of. Little things, chords, planets. And then you’ve got something, where there was nothing.”

Why don’t we do it in Abbey Road?

On July 23, one of the hottest days of the summer, Paul McCartney flung his jacket over his shoulder and strolled over the famous Abbey Road crossing. Word spread: partly because he put a photo on Instagram, where he has 2m followers; mostly because he’s a former Beatle visiting the band’s palace. Fans hang out there all the time, usually taking a selfie with a fence. That day, they saw the actual McCartney and probably hyperventilated. Had they made it into the studio, where he played a long gig, it would have been paramedics all round.

Inside, competition winners stood with McCartney’s family and an A-list guest roster grander than the royal wedding’s. Amy Schumer chatted to Orlando Bloom in the canteen, then McCartney and his band arrived on stage, the same gang he has played with for years. By the 10th song, they had run through A Hard Day’s Night and Drive My Car. The stuff of legend.

The 11th track? Love Me Do, after which McCartney told us that the Beatles hid cannabis use from George Martin in an Abbey Road backroom. He giggles. Johnny Depp smiles for the first time in months. On the solo song My Valentine, McCartney directs a heart shape in his hand to his wife, Nancy, who does it back. The band beam. Everyone beams — then the last two songs take the roof off.

First, it’s the Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band reprise, as melodic and fascinating as it was 50 years ago. Overwhelmed fans summon the energy that only comes from adrenaline. Then the final song is Helter Skelter — so raucous, it threatens infrastructure and hearing. What a couple of hours. He played 25 songs in all, leaving me to stumble into the daylight. I sat for an hour, staring into space.

Her Majesty’s a pretty nice girl

“I was 10 in 1953, when the coronation of Elizabeth II happened. It was a huge event and there were brilliant PR things, such as a coronation essay competition that I entered. I won one of the categories and got prizes. You were allowed to buy any book you wanted, so I got a cool little book on modern art, then they gave you a book on the monarchy. It was fabulous PR. It made you love them. Also, the age gap between a 10-year-old, and she was 27… She was a good-looking woman to us. So we were always fans and, to this day, I think she is the glue. I understand all the arguments, but I would like someone to do the accounting. Money in, money out. Do they bring in as much as, or more than, we spend on them? I don’t know. But I’m a fan. I think she does a hell of a job and I’m proud to be alive during her reign, and one of her subjects.”

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.

Martha Magee • 2 years ago

Brilliant. Sir Paul is a major contributor to the goodness on this planet! Thank you Paul!

Love you and forever. Love you with all my heart! 💖

Martha