Friday, March 4, 1966

John Lennon is quoted saying “We’re more popular than Jesus now”

Last updated on November 7, 2023

Friday, March 4, 1966

Last updated on November 7, 2023

Article March 3 - March 20, 1966 • Paul McCartney and Jane Asher on holiday in Switzerland

Article March 3, 1966 ? • Photo shoot with French photographer Jean-Marie Périer

Article Mar 04, 1966 • John Lennon is quoted saying "We're more popular than Jesus now"

EP Mar 04, 1966 • "Yesterday" by The Beatles released in the UK

Article Mar 15, 1966 • No Grammy Award for The Beatles despite 10 nominations

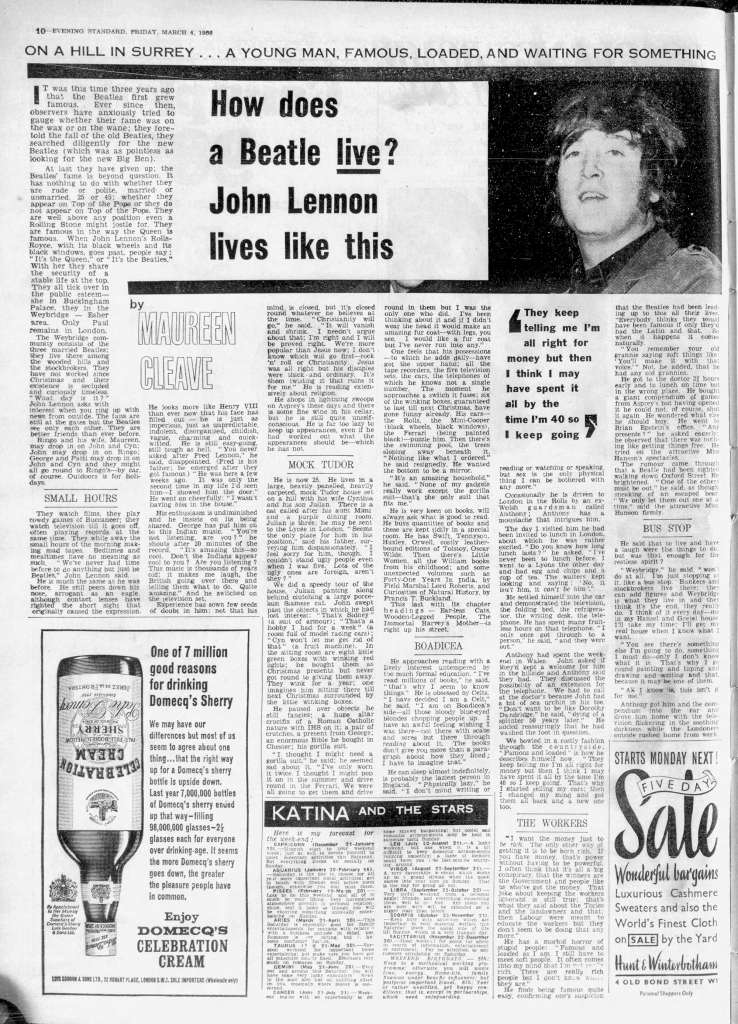

In March 1966, London’s Evening Standard ran a weekly series titled “How Does a Beatle Live?” that featured John Lennon, Ringo Starr, George Harrison and Paul McCartney. The articles were written by Maureen Cleave, who knew the group well and had interviewed them regularly since the start of Beatlemania in the United Kingdom. She had described them three years earlier as “the darlings of Merseyside”, and in February 1964 had accompanied them on their first visit to the United States. She chose to interview the band members individually for the lifestyle series, rather than as a group.

Paul’s interview was published on March 25, 1966. John’s one was published two weeks earlier, March 4, and was entitled “How does a Beatle live? John Lennon lives like this.” At some point in this article, John declared:

Christianity will go. It will vanish and sink. I needn’t argue about that. I’m right and will be proved right. We’re more popular than Jesus now. I don’t know which will go first – rock’n’roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right, but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.

John Lennon

This opinion didn’t create any controversy in the UK. But when the article was republished in July of the same year in the US, it drew angry and threatening reactions from Christian communities, at a time The Beatles were about to tour in the country.

John used to know Maureen Cleave of the London Evening Standard quite well. We’d gravitate to any journalists who were a little better than the average, because we could talk to them. We felt we weren’t stupid rock’n’roll stars. We were interested in other things, and were seen as spokesmen for youth. So Maureen Cleave’s article with John touched on religion, and he started to say something that we’d all felt quite keenly: that the Anglican Church had been going downhill for years. They themselves had been complaining about lack of congregations.

Maureen was interesting and easy to talk to. We all did an in-depth interview with her. In his, John happened to be talking about religion because, although we were not religious, it was something we were interested in.

We used to get a number of Catholic priests showing up at our gigs, and we’d do a lot of debating backstage, about things like the church’s wealth relative to world poverty. We’d say, ‘You should have gospel singing – that’ll pull them in. You should be more lively, instead of singing hackneyed old hymns. Everyone’s heard them and they’re not getting off on them anymore.’

So we felt quite strongly that the church should get its act together. We were actually very pro-church; it wasn’t any sort of demonic, anti-religion point of view that John was trying to express. If you read the whole article, what he was trying to say was something that we all believed in: ! don’t know what’s wrong with the church. At the moment, The Beatles are bigger than Jesus Christ. They’re not building Jesus enough; they ought to do more.’ But he made the unfortunate mistake of talking very freely because Maureen was someone we knew very well, to whom we would just talk straight from the shoulder. Was it a mistake? I don’t know. In the short term, yes. Maybe not in the long term.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

I wasn’t after sensation or anything. What I aimed to do was give the reader a picture of them at that time on that day. They all seemed very happy to do it. For pop singers before that, there were several very important rules. You didn’t make up your own songs. You never said anything that might upset anybody and you never had a point of view. All the Beatles were really very intelligent. They were quite original thinkers. Nobody told them what to think.

Maureen Cleave – 2005 interview – From “Revolver (2022)” book

From Wikipedia:

“More popular than Jesus” is part of a remark made by John Lennon of the Beatles in a March 1966 interview, in which he argued that the public were more infatuated with the band than with Jesus, and that Christian faith was declining to the extent that it might be outlasted by rock music. His opinions drew no controversy when originally published in the London newspaper The Evening Standard, but drew angry reactions from Christian communities when republished in the United States that July.

Lennon’s comments incited protests and threats, particularly throughout the Bible Belt in the Southern United States. Some radio stations stopped playing Beatles songs, records were publicly burned, press conferences were cancelled, and the Ku Klux Klan picketed concerts. The controversy coincided with the band’s 1966 US tour and overshadowed press coverage of their newest album Revolver. Lennon apologised at a series of press conferences and explained that he was not comparing himself to Christ.

The controversy exacerbated the band’s unhappiness with touring, which they never undertook again; Lennon also refrained from touring in his solo career. In 1980, he was murdered by a Christian fan of the Beatles, Mark David Chapman, who later stated that Lennon’s quote was a motivating factor in the killing.

Background

In March 1966, London’s Evening Standard ran a weekly series titled “How Does a Beatle Live?” that featured John Lennon, Ringo Starr, George Harrison and Paul McCartney. The articles were written by Maureen Cleave, who knew the group well and had interviewed them regularly since the start of Beatlemania in the United Kingdom. She had described them three years earlier as “the darlings of Merseyside”, and in February 1964 had accompanied them on their first visit to the United States. She chose to interview the band members individually for the lifestyle series, rather than as a group.

Cleave carried out the interview with Lennon in February at his home, Kenwood, in Weybridge. Her article portrayed him as restless and searching for meaning in his life; he discussed his interest in Indian music and said he gleaned most of his knowledge from reading books. Among Lennon’s many possessions, Cleave found a full-sized crucifix, a gorilla costume, a medieval suit of armour and a well-organised library with works by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Jonathan Swift, Oscar Wilde, George Orwell and Aldous Huxley. Another book, Hugh J. Schonfield’s The Passover Plot, had influenced Lennon’s ideas about Christianity, although Cleave did not refer to it in the article. She mentioned that Lennon was “reading extensively about religion”, and quoted him as saying:

“Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue about that; I’m right and I’ll be proved right. We’re more popular than Jesus now; I don’t know which will go first – rock ‘n’ roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.”

Cleave’s interview with Lennon was published in The Evening Standard on 4 March under the secondary heading “On a hill in Surrey … A young man, famous, loaded, and waiting for something”. The article provoked no controversy in the UK. Church attendance there was in decline and Christian churches were attempting to transform their image, to make themselves more “relevant to modern times”. According to author Jonathan Gould: “The satire comedians had had a field day with the increasingly desperate attempts of the Church to make itself seem more relevant (‘Don’t call me vicar, call me Dick …’).” In 1963, Bishop of Woolwich John A.T. Robinson published Honest to God urging the nation to reject traditional church teachings on morality and the concept of God as an “old man in the sky”, and instead embrace a universal ethic of love. Bryan R. Wilson’s 1966 text Religion in Secular Society explained that increasing secularisation led to British churches being abandoned. However, traditional Christian faith was still strong and widespread in the United States at that time. The theme of religion’s irrelevance in American society had nevertheless been featured in a cover article titled “Is God Dead?” in Time magazine, in an issue dated 8 April 1966.

Both McCartney and Harrison had been baptised in the Roman Catholic Church, but neither of them followed Christianity. In his interview with Cleave, Harrison was also outspoken about organised religion, as well as the Vietnam War and authority figures in general, whether “religious or secular”. He said: “If Christianity’s as good as they say it is, it should stand up to a bit of discussion.” According to author Steve Turner, the British satirical magazine Private Eye responded to Lennon’s comments by featuring a cartoon by Gerald Scarfe that showed him “dressed in heavenly robes and playing a cross-shaped guitar with a halo made out of a vinyl LP”.

Publication in the US

Newsweek made reference to Lennon’s “more popular than Jesus” comments in an issue published in March, and the interview had appeared in Detroit magazine in May. On 3 July, Cleave’s four Beatles interviews were published together in a five-page article in The New York Times Magazine, titled “Old Beatles – A Study in Paradox”. None of these provoked a strong reaction.

Beatles press officer Tony Barrow offered the four interviews to Datebook, an American teen magazine. He believed that the pieces were important to show fans that the Beatles were progressing beyond simple pop music and producing more intellectually challenging work. Datebook was a liberal magazine that addressed subjects such as interracial dating and legalisation of marijuana, so it seemed an appropriate publication for the interviews. Managing editor Danny Fields played a role in shining a spotlight on Lennon’s comments.

Datebook published the Lennon and McCartney interviews on 29 July, in its September “Shout-Out” issue dedicated to controversial youth-orientated themes including recreational drugs, sex, long hair and the Vietnam War. Art Unger, the magazine’s editor, put a quote from Lennon’s interview on the cover: “I don’t know which will go first – rock ‘n’ roll or Christianity!” In author Robert Rodriguez’s description, the editor had chosen Lennon’s “most damning comment” for maximum effect; placed above it on the cover was a quote from McCartney regarding America: “It’s a lousy country where anyone black is a dirty nigger!” Only McCartney’s image was featured on the front cover, as Unger expected that his statement would spark the most controversy. The same Lennon quote appeared as the headline above the feature article. Beside the text, Unger included a photo of Lennon on a yacht, gazing across the ocean with his hand shielding his eyes, accompanied by the caption: “John Lennon sights controversy and sets sail directly towards it. That’s the way he likes to live!”

Escalation and radio bans

In late July, Unger sent copies of the interviews to radio stations in the American South. WAQY disc jockey Tommy Charles in Birmingham, Alabama, heard about Lennon’s remarks from his co-presenter Doug Layton and said, “That does it for me. I am not going to play the Beatles any more.” During their 29 July breakfast show, Charles and Layton asked for listeners’ views on Lennon’s comment, and the response was overwhelmingly negative. The pair set about destroying Beatles vinyl LPs on-air. Charles later stated, “We just felt it was so absurd and sacrilegious that something ought to be done to show them that they can’t get away with this sort of thing.” United Press International bureau manager Al Benn heard the WAQY show and filed a news report in New York City, culminating in a major story in The New York Times on 5 August. Sales of Datebook, which had never been a leading title in the youth magazine market beforehand, reached a million copies.

Lennon’s remarks were deemed blasphemous by some right-wing religious groups. More than 30 radio stations, including some in New York and Boston, followed WAQY’s lead by refusing to play the Beatles’ music. WAQY hired a tree-grinding machine and invited listeners to deliver their Beatles merchandise for destruction. KCBN in Reno, Nevada, broadcast hourly editorials condemning the Beatles and announced a public bonfire for 6 August where the band’s albums would be burned. Several Southern stations organised demonstrations with bonfires, drawing crowds of teenagers to publicly burn their Beatles records, effigies of the band, and other memorabilia. Photos of teenagers eagerly participating in the bonfires were widely distributed throughout the US, and the controversy received blanket media coverage through television reports.

The furore came to be known as the “‘More popular than Jesus’ controversy” or the “Jesus controversy”. It followed soon after the negative reaction from American disc jockeys and retailers to the “butcher” sleeve photo used on the Beatles’ US-only LP Yesterday and Today. Withdrawn and replaced within days of release in June, this LP cover showed the band members dressed as butchers and covered in dismembered plastic dolls and pieces of raw meat. For some conservatives in the American South, according to Rodriguez, Lennon’s comments on Christ now allowed them an opportunity to act on their grievances against the Beatles – namely, their long hair and championing of African-American musicians.

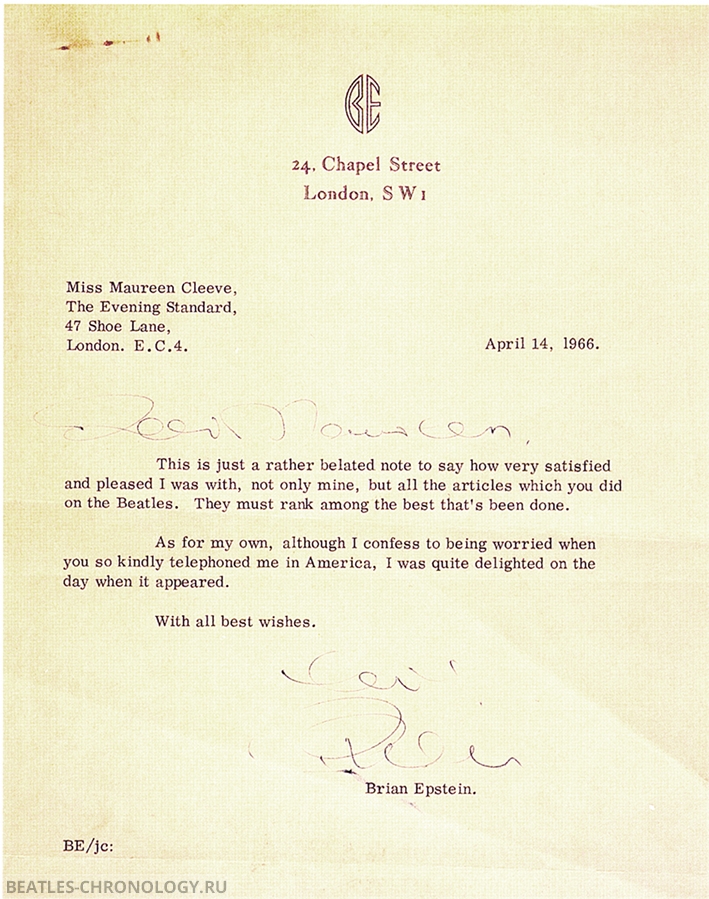

Pre-tour press conferences

According to Unger, Brian Epstein was initially unperturbed about the reaction from the Birmingham disc jockeys, telling him: “Arthur, if they burn Beatles records, they’ve got to buy them first.” Within days, however, Epstein became so concerned by the furore that he considered cancelling the group’s upcoming US tour, fearing that they would be seriously harmed in some way. He flew to New York on 4 August and held a press conference the following day in which he claimed that Datebook had taken Lennon’s words out of context, and expressed regret on behalf of the group that “people with certain religious beliefs should have been offended in any way”. Epstein’s efforts had little effect, as the controversy quickly spread beyond the United States. In Mexico City, there were demonstrations against the Beatles, and a number of countries banned the Beatles’ music on national radio stations, including South Africa and Spain. The Vatican issued a denouncement of Lennon’s comments, saying that “Some subjects must not be dealt with profanely, not even in the world of beatniks.” This international disapproval was reflected in the share price of the Beatles’ Northern Songs publishing company, which dropped by the equivalent of 28 cents on the London Stock Exchange.

In response to the furore in the US, a Melody Maker editorial stated that the “fantastically unreasoned reaction” supported Lennon’s statement regarding Christ’s disciples being “thick and ordinary”. Daily Express columnist Robert Pitman wrote, “It seems a nerve for Americans to hold up shocked hands, when week in, week out, America is exporting to us [in Britain] a subculture that makes the Beatles seem like four stern old churchwardens.” The reaction was also criticised within the US; a Kentucky radio station announced that it would give the Beatles music airplay to show its “contempt for hypocrisy personified”, and the Jesuit magazine America wrote that “Lennon was simply stating what many a Christian educator would readily admit.”

Lennon’s apology

The Beatles left London on 11 August for their US tour. Lennon’s wife Cynthia said that he was nervous and upset because he had made people angry simply by expressing his opinion. The Beatles held a press conference in Barrow’s suite at the Astor Tower Hotel in Chicago. Lennon did not want to apologise but was advised by Epstein and Barrow that he should. Lennon was also distressed that he had potentially endangered the lives of his bandmates by speaking his mind. While preparing to meet the reporters, he broke down in tears in front of Epstein and Barrow. To present a more conservative image for the cameras, the Beatles eschewed their London fashions for dark suits, plain shirts, and neckties.

At the press conference, Lennon said: “I suppose if I had said television was more popular than Jesus, I would have got away with it. I’m sorry I opened my mouth. I’m not anti-God, anti-Christ, or anti-religion. I was not knocking it. I was not saying we are greater or better.” He stressed that he had been remarking on how other people viewed and popularised the Beatles. He described his own view of God by quoting the Bishop of Woolwich, “not as an old man in the sky. I believe that what people call God is something in all of us.” He was adamant that he was not comparing himself with Christ, but attempting to explain the decline of Christianity in the UK. “If you want me to apologise,” he concluded, “if that will make you happy, then OK, I’m sorry.”

Journalists gave a sympathetic response and told Lennon that people in the Bible Belt were “quite notorious for their Christian attitude”. Placated by Lennon’s gesture, Tommy Charles cancelled WAQY’s Beatles bonfire, which had been planned for 19 August, when the Beatles were due to perform in the South. The Vatican’s newspaper L’Osservatore Romano announced that the apology was sufficient, while a New York Times editorial similarly stated that the matter was over, but added, “The wonder is that such an articulate young man could have expressed himself imprecisely in the first place.”

In a private meeting with Unger, Epstein asked him to surrender his press pass for the tour, saying that it had been a “bad idea” for Unger to publish the interviews, and to avoid accusations that Datebook and the Beatles’ management had orchestrated the controversy as a publicity stunt. Epstein assured him that there would be better publishing opportunities for the magazine if he “voluntarily” withdrew from the tour. Unger refused and, in his account, received Lennon’s full support when he later discussed the meeting with him.

US tour incidents

The tour was initially marred by protests and disturbances, and an undercurrent of tension. On 13 August, when the band played in Detroit, images were published of members of the South Carolina Ku Klux Klan “crucifying” a Beatles record on a large wooden cross, which they then ceremoniously burned. That night, the Texas radio station KLUE held a large Beatles bonfire, only for a lightning bolt to strike its transmission tower the following day and send the station temporarily off-air. The Beatles received telephone threats, and the Ku Klux Klan picketed their concerts in Washington, DC, and Memphis, Tennessee. The latter was the tour’s only stop in the Deep South and was expected to be a flashpoint for the controversy. Two concerts took place there at the Mid-South Coliseum on 19 August, although the city council had voted to cancel them rather than have “municipal facilities be used as a forum to ridicule anyone’s religion”, adding that “the Beatles are not welcome in Memphis”.

An ITN news team sent from London to cover the controversy for the program Reporting ’66 held interviews with Charles and with teenagers in Birmingham, many of whom were critical of the Beatles. ITN reporter Richard Lindley also interviewed Robert Shelton, the Ku Klux Klan’s Imperial Wizard, who condemned the band for supporting civil rights and said they were communists. Coinciding with the band’s visit to Memphis, local preacher Jimmy Stroad held a Christian rally to “give the youth of the mid-South an opportunity to show Jesus Christ is more popular than the Beatles”. Outside the Coliseum, a young Klansman told a TV reporter that the Klan were a “terror organization” and would use their “ways and means” to stop the Beatles performing. During the evening show, an audience member threw a firecracker onto the stage, leading the band to believe that they were the target of gunfire.

At press conferences later in the tour, Lennon attempted to avoid the subject of his “Jesus” comments, reasoning that no further discussion was necessary. Rather than shying away from controversy, however, the Beatles became increasingly vocal about topical issues such as the Vietnam War. In Toronto on 17 August, Lennon expressed his approval of Americans who evaded the draft by crossing the border into Canada. At their New York press conference on 22 August, the Beatles shocked reporters by emphatically condemning the Vietnam War as “wrong”.

The Beatles hated the tour, partly due to the controversy and adverse reaction to Lennon’s comments, and they were unhappy about Epstein continuing to organise live performances that were increasingly at odds with their studio work. The controversy had also overshadowed the American release of their 1966 album Revolver, which the band considered to be their best and most mature musical work yet. Following the tour, Harrison contemplated leaving the group, but he decided to remain on the condition that the Beatles would focus solely on studio recording. […]

How does a Beatle live? John Lennon lives like this

It was this time three years ago that The Beatles first grew famous. Ever since then, observers have anxiously tried to gauge whether their fame was on the wax or on the wane; they foretold the fall of the old Beatles, they searched diligently for the new Beatles (which was as pointless as looking for the new Big Ben).

At last they have given up; The Beatles’ fame is beyond question. It has nothing to do with whether they are rude or polite, married or unmarried, 25 or 45; whether they appear on Top Of The Pops or do not appear on Top of the Pops. They are well above any position even a Rolling Stone might jostle for. They are famous in the way the Queen is famous. When John Lennon’s Rolls-Royce, with its black wheels and its black windows, goes past, people say: ‘It’s the Queen,’ or ‘It’s The Beatles.’ With her they share the security of a stable life at the top. They all tick over in the public esteem – she in Buckingham Palace, they in the Weybridge-Esher area. Only Paul remains in London.

The Weybridge community consists of the three married Beatles; they live there among the wooded hills and the stockbrokers. They have not worked since Christmas and their existence is secluded and curiously timeless. ‘What day is it?’ John Lennon asks with interest when you ring up with news from outside. The fans are still at the gates but The Beatles see only each other. They are better friends than ever before.

Ringo and his wife, Maureen, may drop in on John and Cyn; John may drop in on Ringo; George and Pattie may drop in on John and Cyn and they might all go round to Ringo’s, by car of course. Outdoors is for holidays.

They watch films, they play rowdy games of Buccaneer; they watch television till it goes off, often playing records at the same time. They while away the small hours of the morning making mad tapes. Bedtimes and mealtimes have no meaning as such. ‘We’ve never had time before to do anything but just be Beatles,’ John Lennon said.

He is much the same as he was before. He still peers down his nose, arrogant as an eagle, although contact lenses have righted the short sight that originally caused the expression. He looks more like Henry VIII than ever now that his face has filled out – he is just as imperious, just as unpredictable, indolent, disorganised, childish, vague, charming and quick-witted. He is still easy-going, still tough as hell. ‘You never asked after Fred Lennon,’ he said, disappointed. (Fred is his father; he emerged after they got famous.) ‘He was here a few weeks ago. It was only the second time in my life I’d seen him – I showed him the door.’ He went on cheerfully: ‘I wasn’t having him in the house.’

His enthusiasm is undiminished and he insists on its being shared. George has put him on to this Indian music. ‘You’re not listening, are you?’ he shouts after 20 minutes of the record. ‘It’s amazing this – so cool’ Don’t the Indians appear cool to you? Are you listening? This music is thousands of years old; it makes me laugh, the British going over there and telling them what to do. Quite amazing.’ And he switched on the television set.

Experience has sown few seeds of doubt in him: not that his mind is closed, but it’s closed round whatever he believes at the time. ‘Christianity will go,’ he said. ‘It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue about that; I’m right and I will be proved right. We’re more popular than Jesus now; I don’t know which will go first – rock ‘n’ roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.’ He is reading extensively about religion.

He shops in lightning swoops on Asprey’s these days and there is some fine wine in his cellar, but he is still quite unselfconscious. He is far too lazy to keep up appearances, even if he had worked out what the appearances should be – which he has not.

He is now 25. He lives in a large, heavily panelled, heavily carpeted, mock Tudor house set on a hill with his wife Cynthia and his son Julian. There is a cat called after his aunt Mimi, and a purple dining room. Julian is three; he may be sent to the Lycde in London. ‘Seems the only place for him in his position,’ said his father, surveying him dispassionately. ‘I feel sorry for him, though. I couldn’t stand ugly people even when I was five. Lots of the ugly ones are foreign, aren’t they?’

We did a speedy tour of the house, Julian panting along behind, clutching a large porcelain Siamese cat. John swept past the objects in which he had lost interest: ‘That’s Sidney’ (a suit of armour); ‘That’s a hobby I had for a week’ (a room full of model racing cars); ‘Cyn won’t let me get rid of that'(a fruit machine). In the sitting room are eight little green boxes with winking red lights; he bought them as Christmas presents but never got round to giving them away. They wink for a year; one imagines him sitting there till next Christmas, surrounded by the little winking boxes.

He paused over objects he still fancies; a huge altar crucifix of a Roman Catholic nature with IHS on it; a pair of crutches, a present from George; an enormous Bible he bought in Chester; his gorilla suit.

‘I thought I might need a gorilla suit,’ he said; he seemed sad about it. ‘I’ve only worn it twice. I thought I might pop it on in the summer and drive round in the Ferrari. We were all going to get them and drive round in them but I was the only one who did. I’ve been thinking about it and if I didn’t wear the head it would make an amazing fur coat – with legs, you see. I would like a fur coat but I’ve never run into any.’

One feels that his possessions – to which he adds daily – have got the upper hand; all the tape recorders, the five television sets, the cars, the telephones of which he knows not a single number. The moment he approaches a switch it fuses; six of the winking boxes, guaranteed to last till next Christmas, have gone funny already. His cars – the Rolls, the Mini-Cooper (black wheels, black windows), the Ferrari (being painted black) – puzzle him. Then there’s the swimming pool, the trees sloping away beneath it. ‘Nothing like what I ordered,’ he said resignedly. He wanted the bottom to be a mirror. ‘It’s an amazing household,’ he said. ‘None of my gadgets really work except the gorilla suit – that’s the only suit that fits me.’

He is very keen on books, will always ask what is good to read. He buys quantities of books and these are kept tidily in a special room. He has Swift, Tennyson, Huxley, Orwell, costly leather-bound editions of Tolstoy, Oscar Wilde. Then there’s Little Women, all the William books from his childhood; and some unexpected volumes such as Forty-One Years In India, by Field Marshal Lord Roberts, and Curiosities of Natural History, by Francis T Buckland. This last – with its chapter headings ‘Ear-less Cats’, ‘Wooden-Legged People,’ ‘The Immortal Harvey’s Mother’ – is right up his street.

He approaches reading with a lively interest untempered by too much formal education. ‘I’ve read millions of books,’ he said, ‘that’s why I seem to know things.’ He is obsessed by Celts. ‘I have decided I am a Celt,’ he said. ‘I am on Boadicea’s side – all those bloody blue-eyed blondes chopping people up. I have an awful feeling wishing I was there – not there with scabs and sores but there through reading about it. The books don’t give you more than a paragraph about how they lived; I have to imagine that.’

He can sleep almost indefinitely, is probably the laziest person in England. ‘Physically lazy,’ he said. ‘I don’t mind writing or reading or watching or speaking, but sex is the only physical thing I can be bothered with any more.’ Occasionally he is driven to London in the Rolls by an ex-Welsh guardsman called Anthony; Anthony has a moustache that intrigues him.

The day I visited him he had been invited to lunch in London, about which he was rather excited. ‘Do you know how long lunch lasts?’ he asked. ‘I’ve never been to lunch before. I went to a Lyons the other day and had egg and chips and a cup of tea. The waiters kept looking and saying: “No, it isn’t him, it can’t be him”.’

He settled himself into the car and demonstrated the television, the folding bed, the refrigerator, the writing desk, the telephone. He has spent many fruitless hours on that telephone. ‘I only once got through to a person,’ he said, ‘and they were out.’

Anthony had spent the weekend in Wales. John asked if they’d kept a welcome for him in the hillside and Anthony said they had. They discussed the possibility of an extension for the telephone. We had to call at the doctor’s because John had a bit of sea urchin in his toe. ‘Don’t want to be like Dorothy Dandridge,’ he said, ‘dying of a splinter 50 years later.’ He added reassuringly that he had washed the foot in question.

We bowled along in a costly fashion through the countryside. ‘Famous and loaded’ is how he describes himself now. ‘They keep telling me I’m all right for money but then I think I may have spent it all by the time I’m 40 so I keep going. That’s why I started selling my cars; then I changed my mind and got them all back and a new one too.

‘I want the money just to be rich. The only other way of getting it is to be born rich. If you have money, that’s power without having to be powerful. I often think that it’s all a big conspiracy, that the winners are the Government and people like us who’ve got the money. That joke about keeping the workers ignorant is still true; that’s what they said about the Tories and the landowners and that; then Labour were meant to educate the workers but they don’t seem to be doing that any more.’

He has a morbid horror of stupid people: ‘Famous and loaded as I am, I still have to meet soft people. It often comes into my mind that I’m not really rich. There are really rich people but I don’t know where they are.’

He finds being famous quite easy, confirming one’s suspicion that The Beatles had been leading up to this all their lives. ‘Everybody thinks they would have been famous if only they’d had the Latin and that. So when it happens it comes naturally. You remember your old granny saying soft things like: “You’ll make it with that voice.”‘ Not, he added, that he had any old grannies.

He got to the doctor 2 3/4 hours early and to lunch on time but in the wrong place. He bought a giant compendium of games from Asprey’s but having opened it he could not, of course, shut it again. He wondered what else he should buy. He went to Brian Epstein’s office. ‘Any presents?’ he asked eagerly; he observed that there was nothing like getting things free. He tried on the attractive Miss Hanson’s spectacles.

The rumour came through that a Beatle had been sighted walking down Oxford Street! He brightened. ‘One of the others must be out,’ he said, as though speaking of an escaped bear. ‘We only let them out one at a time,’ said the attractive Miss Hanson firmly.

He said that to live and have a laugh were the things to do; but was that enough for the restless spirit?

‘Weybridge,’ he said, ‘won’t do at all. I’m just stopping at it, like a bus stop. Bankers and stockbrokers live there; they can add figures and Weybridge is what they live in and they think it’s the end, they really do. I think of it every day – me in my Hansel and Gretel house. I’ll take my time; I’ll get my real house when I know what I want.

‘You see, there’s something else I’m going to do, something I must do – only I don’t know what it is. That’s why I go round painting and taping and drawing and writing and that, because it may be one of them. All I know is, this isn’t it for me.’

Anthony got him and the compendium into the car and drove him home with the television flickering in the soothing darkness while the Londoners outside rushed home from work.

From London Evening Standard, March 4, 1966

The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years

"With greatly expanded text, this is the most revealing and frank personal 30-year chronicle of the group ever written. Insider Barry Miles covers the Beatles story from childhood to the break-up of the group."

We owe a lot to Barry Miles for the creation of those pages, but you really have to buy this book to get all the details - a day to day chronology of what happened to the four Beatles during the Beatles years!

If we modestly consider the Paul McCartney Project to be the premier online resource for all things Paul McCartney, it is undeniable that The Beatles Bible stands as the definitive online site dedicated to the Beatles. While there is some overlap in content between the two sites, they differ significantly in their approach.

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.