Timeline

More from year 1967

Spread the love! If you like what you are seeing, share it on social networks and let others know about The Paul McCartney Project.

About

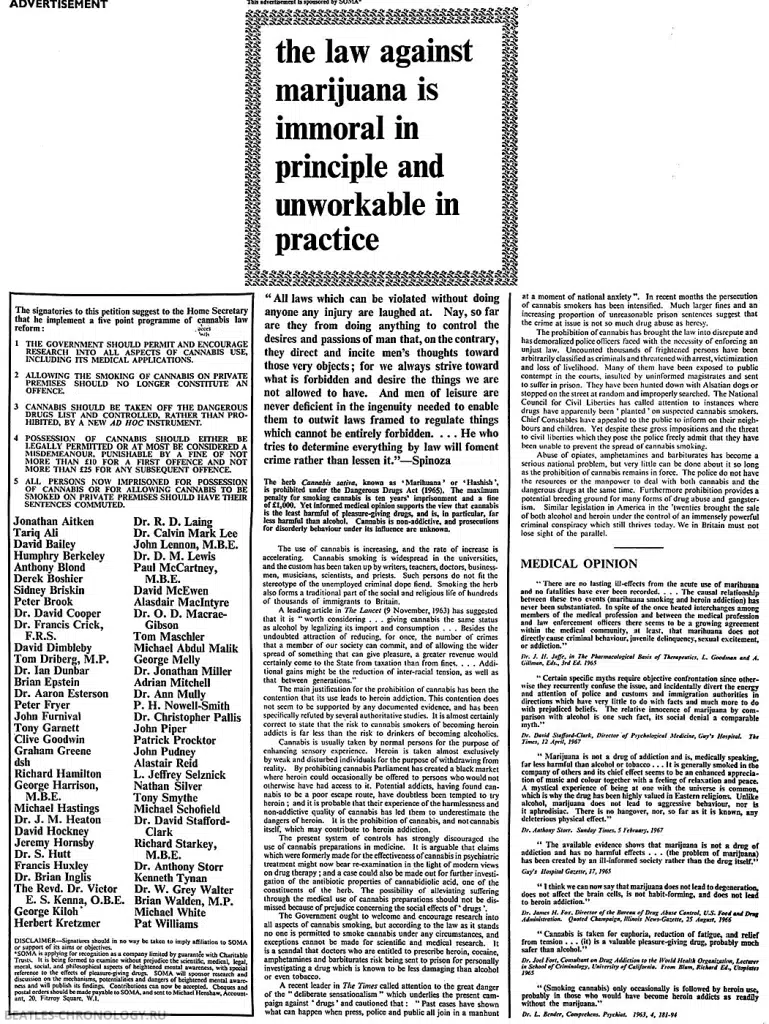

On July 24, 1967, a full-page advertisement titled “The law against marijuana is immoral in principle and unworkable in practice” was published in The Times newspaper. The ad was signed by 65 eminent personalities, including the four Beatles and Brian Epstein. The petitioners proposed a five-point program for cannabis law reform, which included allowing research, removing the criminal penalty for smoking on private premises, regulating cannabis, allowing possession or considering possession as a minor offence with a fine, and commuting sentences of imprisoned offenders.

The Beatles paid £1,800 for the advertisement at Paul McCartney’s instigation. On June 3, 1967, Paul met with Barry Miles and drug researcher Steve Abram, who suggested publishing this advertisement.

While I felt a bit stranded by Jimi [Hendrix]’s psychedelic genius, I felt equally out of the loop when drugs became a political issue for those of us in the music business – Paul McCartney had gone on TV saying marijuana should be legalised, for example. It might appear that I felt threatened by talented people, or those brave enough to live a wilder life, and there’s some truth in that, but mostly I felt out of synch, a few steps behind.

Pete Townshend – From “Who I Am“, 2012

From Wikipedia:

Stephen Irwin Abrams (15 July 1938 in Chicago, Illinois – 21 November 2012) was an American scholar of parapsychology and a cannabis rights activist who was a long-standing resident of the United Kingdom. He is best known for sponsoring and authoring the full-page advertisement petitioning for cannabis law reform which appeared in The Times on 24 July 1967. […]

Oxford and the founding of SOMA

Abrams was an Advanced Student at St. Catherine’s College of Oxford University from 1960 to 1967. He headed a parapsychological laboratory in the university’s Department of Biometry, investigating extrasensory perception.

In January 1967, the content of an article by Abrams “The Oxford Scene and the Law”, intended as a contribution to a forthcoming book The Book of Grass was republished, without his permission, in The People Sunday newspaper. The article was a balanced reasoning on the social and personal effects of cannabis use and its repression. The article observed that under current laws cannabis users were punished more severely than heroin users. Cannabis smoking was regarded as a crime but heroin addiction was treated as an illness. Doctors had the right to prescribe heroin. The Court might send a cannabis smoker to prison and send a heroin user to a doctor. Presented in the sensationalist manner for which the paper was known, the story emphasized Abrams claim that 500 of Oxford’s student body were cannabis users. The story spread. Headlines like “Smoke more pot. It’s safer than beer”, appeared in the popular press. On 1 February, the same day as long clarifying letter from him was printed in The Daily Telegraph, Abrams announced, via the pages of student newspaper Cherwell, the formation of SOMA, an acronym for the Society of Mental Awareness, as a drug research project. Two weeks later, on 15 February 1967, Abrams gave evidence before the University Committee on Student Health, which agreed to pursue his suggestion that the Home Secretary be prevailed upon to institute an inquiry. After the committee’s published report received national press coverage, on 7 April 1967 home secretary Roy Jenkins appointed a “sub-committee on hallucinogens” to be chaired by Baroness Wootton to report to the Advisory Council on Drug Dependence, itself appointed four months earlier in December 1966.

Protests and organizing The Times advertisement

Public awareness had been increased by the February arrests of Keith Richards and Mick Jagger on drug charges. In the midst of Abrams campaign in Oxford, on March 1, 1967, activist Hoppy had organized a happening in Oxford that had turned into an impromptu “pot protest”. Swelled by rowdy participants from Oxford Polytechnic’s rag week, the event gained national coverage. Hoppy himself, a member of the editorial board of the underground newspaper International Times, had been arrested for cannabis possession the previous December, after police raided his London flat. Although the amount was small, he had a previous conviction, so this was a serious matter. Out on bail, Hoppy went on to organize the massive 14 Hour Technicolor Dream multimedia event at Alexandra Palace on April 29. In his drug case – despite having no defense – he insisted on pleading ‘Not Guilty’, elected for trial by jury, and lectured the court on the iniquity of the law. Needless to say he was found guilty. On June 1, 1967, he was sentenced to 9 months in prison by a judge who called him a “pest to society”. He rapidly became a cause célèbre and a ‘Free Hoppy’ movement was born.

On 2 June, at a gathering of Hoppy supporters, Abrams launched the idea of a SOMA advertisement in The Times petitioning for reform. The idea was that this could serve the double purpose of raising awareness of Hoppy’s case and to influence the Wootton Committee, who everyone thought was going to legalise cannabis use. Barry Miles introduced Abrams to Paul McCartney who was persuaded to anonymously donate the £1,800 cost. McCartney had recently blurted to the press about his LSD use. Controversy raged over lyrics suggestive of drug use on the Sgt. Pepper’s album, released on 1 June . After word got out of his backing of the advertisement his support wavered. Abrams was able to convince McCartney that associating The Beatles with the cannabis cause could serve to direct all the attention in a positive direction. The space was booked for The Times of Monday 24 July 1967, and Abrams set about recruiting signatories.

He was helped by circumstances. On 29 June 1967, the sentencing of Richards and Jagger to lengthy jail sentences precipitated spontaneous protests on Fleet Street outside the offices of the News of the World, widely seen as having instigated the police action after Jagger had threatened them with a libel action over drug allegations earlier in the year. The protests met with violent police responses, including the use of dogs. Jagger and Richards were freed on bail the next day, Friday 30 June. At midnight that day the entire crowd at underground club UFO and many others, including Abrams, again marched to the News of the World to demonstrate. After a third night of protests, again met with police violence, Abrams was among those whose picture appeared on the News of the World‘s front page on 2 July.

The next big event was a “Legalize Pot Rally” at Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park on Sunday 16 July. A permit having been refused for a larger event, the protesters led by Abrams – and including speakers Allen Ginsberg, Caroline Coon, Stokely Carmichael, Alexis Korner, Spike Hawkins, Clive Goodwin and Adrian Mitchell – split into small groups in this famous haven of free speech. Again wide publicity was gained, and International Times commented “Vast publicity for legalize pot rally. Steve Abrams appears on television with amazing regularity”

The Times advertising department were still apprehensive. Abrams speculated around 1988 that, if it were not for the furor over the Rolling Stones case – which included the famous William Rees-Mogg editorial Who breaks a butterfly upon a wheel? on July 1 – they would have balked. As it was, at the last moment they demanded payment in advance. Abrams called The Beatles office Apple and assistant Pete Brown came up with a personal cheque to save the day.

A week after the advertisement appeared, on 31 July 1967, Keith Richards’ cannabis conviction was quashed, and Mick Jagger’s prison sentence (for possession of amphetamine tablets) reduced to a conditional discharge.

The Times advertisement

The advertisement appeared in The Times on 24 July 1967. A full page, it stated: ‘The law against marijuana is immoral in principle and unworkable in practice.’

The advertisement went on to present medical sources asserting the harmlessness of cannabis, and recommended a five-point plan:

- The government should permit and encourage research into all aspects of cannabis use, including its medical applications.

- Allowing the smoking of cannabis on private premises should no longer constitute an offence.

- Cannabis should be taken off the dangerous drugs list and controlled, rather than prohibited, by a new ad hoc instrument.

- Possession of cannabis should either be legally permitted or at most be considered a misdemeanour, punishable by a fine of not more than £10 for a first offence and not more than £25 for any subsequent offence.

- All persons now imprisoned for possession of cannabis or for allowing cannabis to be smoked on private premises should have their sentences commuted.

The sixty-five signatories comprised leading names in British society, including Nobel Laureate Francis Crick, novelist Graham Greene, Members of Parliament Tom Driberg and Brian Walden, photographer David Bailey, directors Peter Brook and Jonathan Miller, broadcaster David Dimbleby, psychiatrists R. D. Laing, David Cooper, and David Stafford-Clark, the critic Kenneth Tynan, scientist Francis Huxley, activist Tariq Ali, and The Beatles, along with their manager Brian Epstein.

The advertisement was controversial, receiving both public support and establishment condemnation. It was discussed in Parliament. At the 1967 Tory party conference, the Shadow Home Secretary, Quintin Hogg said he was “profoundly shocked by the irresponsibility of those who wanted to change the law“, describing their arguments as “casuistic, confused, sophistical and immature.“

The Wootton Committee’s Report, when submitted in November 1968, specifically cited the advertisement’s influence on its proceedings, noting that the advertisement’s claim that “the long-asserted dangers of cannabis are exaggerated and that the related law is socially damaging, if not unworkable’, had caused the committee to “give greater attention to the legal aspects of the problem” and “give first priority to presenting our views on cannabis.” The Report vindicated much of the advertisement’s position, stating “the long-term consumption of cannabis in moderate doses has no harmful effects.”, that cannabis was “no more dangerous than alcohol” and that prison only be recommended for cases of “organised large-scale trafficking” and all other offenders be given, at the worst, suspended sentences. The Home Secretary of the day, James Callaghan denounced the Report, claiming its authors had been “overinfluenced” by the “lobby” responsible for “that notorious advertisement.” However he later quietly reversed his position, and many of the Report’s recommendations became law in 1971 – ironically enacted by Hogg who, after a change of government, had taken over as Home Secretary. […]

The law against marijuana is immoral in principle and unworkable in practice

“All laws which can be violated without doing anyone any injury are laughed at. Nay, so far are they from doing anything to control the desires and passions of man that, on the contrary, they direct and incite men’s thoughts toward those very objects; for we always strive toward what is forbidden and desire the things we are not allowed to have. And men of leisure are never deficient in the ingenuity needed to enable them to outwit laws framed to regulate things which cannot be entirely forbidden. … He who tries to determine everything by law will foment crime rather than lessen it.” — Spinoza

The herb Cannabis sativa, known as ‘Marihuana’ or ‘Hashish’ is prohibited under the Dangerous Drugs Act (1965). The maximum penalty for smoking cannabis is ten years’ imprisonment and a fine of £1,000. Yet informed medical opinion supports the view that cannabis is the least harmful of pleasure-giving drugs, and is, in particular, far less harmful than alcohol. Cannabis is non-addictive, and prosecutions for disorderly behaviour under its influence are unknown.

The use of cannabis is increasing, and the rate of increase is accelerating. Cannabis smoking is widespread in the universities, and the custom has been taken up by writers, teachers, doctors, businessmen, musicians, scientists, and priests. Such persons do not fit the stereotype of the unemployed criminal dope fiend. Smoking the herb also forms a traditional part of the social and religious life of hundreds of thousands of immigrants to Britain.

A leading article in The Lancet (9 November, 1963) has suggested that it is “worth considering… giving cannabis the same status as alcohol by legalizing its import and consumption… Besides the undoubted attraction of reducing, for once, the number of crimes that a member of our society can commit, and of allowing the wider spread of something that can give pleasure, a greater revenue would certainly come to the State from taxation than from fines… Additional gains might be the reduction of inter-racial tension, as well as that between generations.”

The main justification for the prohibition of cannabis has been the contention that its use leads to heroin addiction. This contention does not seem to be supported by any documented evidence, and has been specifically refuted by several authoritative studies. It is almost certainly correct to state that the risk to cannabis smokers of becoming heroin addicts is far less than the risk to drinkers of becoming alcoholics.

Cannabis is usually taken by normal persons for the purpose of enhancing sensory experience. Heroin is taken almost exclusively by weak and disturbed individuals for the purpose of withdrawing from reality. By prohibiting cannabis Parliament has created a black market where heroin could occasionally be offered to persons who would not otherwise have had access to it. Potential addicts, having found cannabis to be a poor escape route, have doubtless been tempted to try heroin ; and it is probable that their experience of the harmlessness and non-addictive quality of cannabis has led them to underestimate the dangers of heroin. It is the prohibition of cannabis, and not cannabis itelf, which may contribute to heroin addiction.

The present system of controls has strongly discouraged the use of cannabis preparations in medicine. It is arguable that claims which were formerly made for the effectiveness of cannabis in psychiatric treatment might now bear reexamination in the light of modern views on drug therapy; and a case could also be made out for further investigation of the antibiotic properties of cannabidiolic acid, one of the constituents of the herb. The possibility of alleviating suffering through the medical use of cannabis preparations should not be dismissed because of prejudice concerning the social effects of ‘drugs’.

The Government ought to welcome and encourage research into all aspects of cannabis smoking, but according to the law as it stands no one is permitted to smoke cannabis under any circumstances, and exceptions cannot be made for scientific and medical research. It is a scandal that doctors who are entitled to prescribe heroin, cocaine, amphetamines and barbiturates risk being sent to prison for personally investigating a drug which is known to be less damaging than alcohol or even tobacco.

A recent leader in The Times called attention to the great danger of the “deliberate sensationalism” which underlies the present campaign against ‘drugs’ and cautioned that: “Past cases have shown what can happen when press, police and public all join in a manhunt at a moment of national anxiety”. In recent months the persecution of cannabis smokers has been intensified. Much larger fines and an increasing proportion of unreasonable prison sentences suggest that the crime at issue is not so much drug abuse as heresy.

The prohibition of cannabis has brought the law into disrepute and has demoralized police officers faced with the necessity of enforcing an unjust law. Uncounted thousands of frightened persons have been arbitrarily classified as criminals and threatened with arrest, victimization and loss of livelihood. Many of them have been exposed to public contempt in the courts, insulted by uninformed magistrates and sent to suffer in prison. They have been hunted down with Alsatian dogs or stopped on the street at random and improperly searched. The National Council for Civil Liberties has railed attention to instances where drugs have apparently been ‘planted’ on suspected cannabis smokers. Chief Constables have appealed to the public to inform on their neighbours and children. Yet despite these gross impositions and the threat to civil liberties which they pose the police freely admit that they have been unable to prevent the spread of cannabis smoking.

Abuse of opiates, amphetamines and barbiturates has become a serious national problem, but very little can be done about it so long as the prohibition of cannabis remains in force. The police do not have the resources or the manpower to deal with both cannabis and the dangerous drugs at the same time. Furthermore prohibition provides a potential breeding ground for many forms of drug abuse and gangsterism. Similar legislation in America in the ‘twenties brought the sale of both alcohol and heroin under the control of an immensely powerful criminal conspiracy which still thrives today. We in Britain must not lose sight of the parallel.

The signatories to this petition suggest to the Home Secretary that he implement a five point programme of cannabis law reform:

From The Times, July 24, 1967

- 1. THE GOVERNMENT SHOULD PERMIT AND ENCOURAGE RESEARCH INTO ALL ASPECTS OF CANNABIS USE, INCLUDING ITS MEDICAL APPLICATIONS.

- 2 ALLOWING THE SMOKING OF CANNABIS ON PRIVATE PREMISES SHOULD NO LONGER CONSTITUTE AN OFFENCE.

- 3 CANNABIS SHOULD BE TAKEN OFF THE DANGEROUS DRUGS LIST AND CONTROLLED, RATHER THAN PROHIBITED, BY A NEW AD HOC INSTRUMENT.

- 4 POSSESSION OF CANNABIS SHOULD EITHER BE LEGALLY PERMITTED OR AT MOST BE CONSIDERED A MISDEMEANOUR, PUNISHABLE BY A FINE OF NOT MORE THAN £10 FOR A FIRST OFFENCE AND NOT MORE THAN £25 FOR ANY SUBSEQUENT OFFENCE.

- 5 ALL PERSONS NOW IMPRISONED FOR POSSESSION OF CANNABIS OR FOR ALLOWING CANNABIS TO BE SMOKED ON PRIVATE PREMISES SHOULD HAVE THEIR SENTENCES COMMUTED.

Last updated on May 9, 2024

Going further

The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years

"With greatly expanded text, this is the most revealing and frank personal 30-year chronicle of the group ever written. Insider Barry Miles covers the Beatles story from childhood to the break-up of the group."

We owe a lot to Barry Miles for the creation of those pages, but you really have to buy this book to get all the details - a day to day chronology of what happened to the four Beatles during the Beatles years!

Contribute!

Have you spotted an error on the page? Do you want to suggest new content? Or do you simply want to leave a comment ? Please use the form below!