Spread the love! If you like what you are seeing, share it on social networks and let others know about The Paul McCartney Project.

About

From Wikipedia:

William Seward Burroughs II (/ˈbʌroʊz/; February 5, 1914 – August 2, 1997) was an American writer and visual artist. He is widely considered a primary figure of the Beat Generation and a major postmodern author who influenced popular culture and literature. Burroughs wrote eighteen novels and novellas, six collections of short stories and four collections of essays, and five books have been published of his interviews and correspondences; he was initially briefly known by the pen name William Lee. He also collaborated on projects and recordings with numerous performers and musicians, made many appearances in films, and created and exhibited thousands of visual artworks, including his celebrated “Shotgun Art”.

Burroughs was born into a wealthy family in St. Louis, Missouri. He was a grandson of inventor William Seward Burroughs I, who founded the Burroughs Corporation, and a nephew of public relations manager Ivy Lee. Burroughs attended Harvard University, studied English, studied anthropology as a postgraduate, and attended medical school in Vienna. In 1942, Burroughs enlisted in the U.S. Army to serve during World War II. After being turned down by the Office of Strategic Services and the Navy, he developed a heroin addiction that affected him for the rest of his life, initially beginning with morphine. In 1943, while living in New York City, he befriended Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. Their mutual influence became the foundation of the Beat Generation, which was later a defining influence on the 1960s counterculture. Burroughs found success with his confessional first novel, Junkie (1953), but is perhaps best known for his third novel, Naked Lunch (1959). Naked Lunch became the subject of one of the last major literary censorship cases in the United States after its US publisher, Grove Press, was sued for violating a Massachusetts obscenity statute.

Burroughs killed his second wife, Joan Vollmer, in 1951 in Mexico City. Burroughs initially claimed that he shot Vollmer while drunkenly attempting a “William Tell” stunt. He later told investigators that he had been showing his pistol to friends when it fell and hit the table, firing the bullet that killed Vollmer. After Burroughs returned to the United States, he was convicted of manslaughter in absentia and received a two-year suspended sentence.

While heavily experimental and featuring unreliable narrators, much of Burroughs’ work is semiautobiographical, and was often drawn from his experiences as a heroin addict. He lived variously in Mexico City, London, Paris and the Tangier International Zone near Morocco, and traveled in the Amazon rainforest, with these locations featuring in many of his novels and stories. With Brion Gysin, Burroughs popularized the cut-up, an aleatory literary technique, featuring heavily in works such as The Nova Trilogy (1961–1964). Burroughs’ work also features frequent mystical, occult, or otherwise magical themes, which were a constant preoccupation for Burroughs, both in fiction and in real life.

In 1983, Burroughs was elected to the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. In 1984, he was awarded the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by France. Jack Kerouac called Burroughs the “greatest satirical writer since Jonathan Swift”; he owed this reputation to his “lifelong subversion” of the moral, political, and economic systems of modern American society, articulated in often darkly humorous sardonicism. J. G. Ballard considered Burroughs to be “the most important writer to emerge since the Second World War”, while Norman Mailer declared him “the only American writer who may be conceivably possessed by genius”. […]

In early 1966, Paul McCartney and Barry Miles decided to establish a small recording studio for avant-garde artists to record their work. Paul rented Ringo Starr’s apartment at Montagu Square in March 1966, for that purpose.

Paul installed sound recording equipment in the premises with the help of Ian Somerville, an electronics technician, and computer programmer (and boyfriend of William Burroughs). They experimented with tape loops to create avant-garde sounds and recorded spoken word performances of poets, including William Burroughs. While at Montagu Square, Paul also worked on the composition of “Eleanor Rigby”.

In 1966, Paul McCartney, myself, Marianne Faithful and John Dunbar had the idea that we should bring out a monthly magazine in record form. There’d be somebody at all the good poetry readings, we’d have a few snatches of groups rehearsing, and I would be going out doing interviews for International Times and we could do bits of those on tape. As you can imagine, we smoked an enormous amount of dope and thought this was the greatest idea in the world. So we needed someone to operate the tape recorders and nobody knew anyone who could do this except me. Ian Sommerville knew a lot about tape recorders. We also needed a studio and Ringo had this old flat that he wasn’t using in Montagu Square, a ridiculous pad with green silk wallpaper, and he said we could have that. Ian actually moved in there. I don’t think he was supposed to, it was supposed to be the studio. Bill [William Burrough] never moved in, to my knowledge, although when you went to see Ian there, Bill was usually mucking about, but he kept out of the way because he definitely had the impression that this thing was somehow to do with the Beatles and he wasn’t supposed to be there.

Barry Miles – From “With William Burroughs : a report from the bunker” by Victor Bockris, 1996

It was kind of uneasy there… This was when the Beatles were just getting into the possibilities of overlaying, running backwards, the full technical possibilities of the tape recorder. And Ian was a brilliant technician along those lines. Ian met Paul McCartney and Paul put up the money for this flat which was at 54 Montagu Square. There were people like bodyguards and managers who didn’t like this at all and they were always threatening to come around and take the equipment away. I saw Paul several times. The three of us talked about the possibilities of the tape recorder. He’d just come in and work on his “Eleanor Rigby.” Ian recorded his rehearsals. I saw the song taking shape. Once again, not knowing much about music, I could see that he knew what he was doing. He was very pleasant and very prepossessing. Nice-looking young man, hardworking.

William S. Burroughs – From “With William Burroughs : a report from the bunker” by Victor Bockris, 1996

I recall one day when Peter Asher, Ian, and I were there. Bill [William Burrough] was there but sort of distant and not spending much time in the room, always doing things in other rooms. Paul arrived with the acetates for “Rubber Soul”. That was the first time anybody’d ever heard those; they’d just finished mixing them. We were talking about what direction rock music was going to go in, no doubt toward electronic music, but no one knew what they really meant. In those days digital technology didn’t really exist. We all knew that somehow there was going to be a combination of electronics and rock that would be really exciting and that music had gone beyond the barriers of just a bunch of guys playing instruments. Bill and Paul were talking about this.

Barry Miles – From “With William Burroughs : a report from the bunker” by Victor Bockris, 1996

In our conversations, I thought about getting into cut-ups and things like that and I thought I would use the studio for cutups. But it ended up being of more practical use to me, really. I thought, let Burroughs do the cut-ups and I’ll just go in and demo things. I’d just written ‘Eleanor Rigby’ and so I went down there in the basement on my days off on my own. Just took a guitar down and used it as a demo studio.

Paul McCartney – From “Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now” by Barry Miles, 1997

Occasionally Burroughs would be there. He was very interesting but we never really struck up a huge conversation. I actually felt you had to be a bit of a junkie, which was probably not true. He was fine, there never was a problem, it just never really developed into a huge conversation where we sat down for hours together. The sitting around for hours would be more with Ian Sommerville and his friend Alan. I remember them telling me off for being a tea-head. ‘You’re a tea-head, man!’ ‘Well? So?’

Paul McCartney – From “Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now” by Barry Miles, 1997

Allen Ginsberg told me [Eleanor Rigby] was a great poem, so I’m going to go with Allen. He was no slouch. Another early admirer of the song was William S. Burroughs who, of course, also ended up on the cover of Sgt. Pepper. He and I had met through the author Barry Miles and the Indica Bookshop, and he actually got to see the song take shape when I sometimes used the spoken-word studio that we had set up in the basement of Ringo’s flat in Montagu Square. The plan for the studio was to record poets – something we did more formally a few years later with the experimental Zapple label, a subsidiary of Apple. I’d been experimenting with tape loops a lot around this time, using a Brenell reel-to-reel – which I still own – and we were starting to put more experimental elements into our songs. ‘Eleanor Rigby’ ended up on the Revolver album, and for the first time we were recording songs that couldn’t be replicated on stage – songs like this and ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’. So, Burroughs and I had hung out, and he’d borrowed my reel-to-reel a few times to work on his cut-ups. When he got to hear the final version of ‘Eleanor Rigby’, he said he was impressed by how much narrative I’d got into three verses. And it did feel like a breakthrough for me lyrically – more of a serious song.

Paul McCartney – From “The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present“, 2021

William S. Burroughs had what he called his ‘cut-up technique’. I have from time to time been a devotee of something along those lines – just dragging in words and slinging them around, throwing them up in the air, seeing where they fall. You think, ‘Well, that can’t mean anything.’ But then you read it, and it does seem to mean something.

Paul McCartney – From “The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present“, 2021

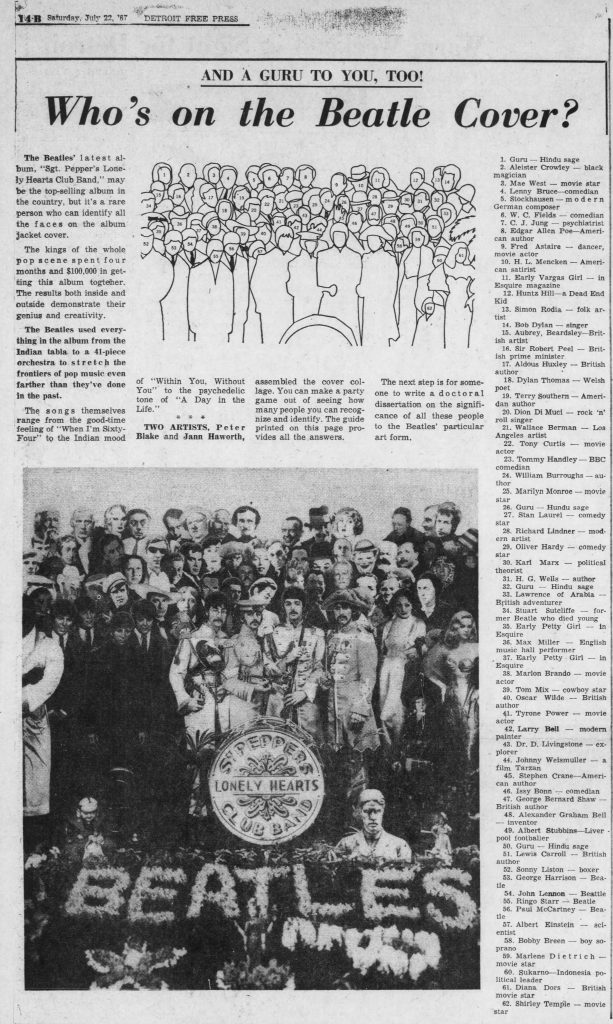

In 1967, William S. Burroughs appeared on the cover of “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” (in slot #24 in the picture below).

Contribute!

Have you spotted an error on the page? Do you want to suggest new content? Or do you simply want to leave a comment ? Please use the form below!