Album This song officially appears on the Revolver (UK Mono) LP.

Timeline This song was officially released in 1966

Timeline This song was written, or began to be written, in 1966, when Paul McCartney was 24 years old)

This song was recorded during the following studio sessions:

You can take Eleanor Rigby and you can apply it to today, there’s still lots and lots of lonely people

Paul McCartney, from Twitter, January 9, 2020

From Wikipedia:

“Eleanor Rigby” is a song by the English rock band the Beatles from their 1966 album Revolver. It was also issued on a double A-side single, paired with “Yellow Submarine“. The song was written primarily by Paul McCartney and credited to Lennon–McCartney.

“Eleanor Rigby” continued the transformation of the Beatles from a mainly rock and roll- and pop-oriented act to a more experimental, studio-based band. With a double string quartet arrangement by George Martin and lyrics providing a narrative on loneliness, it broke sharply with popular music conventions, both musically and lyrically. The song topped singles charts in Australia, Belgium, Canada and New Zealand.

Background and inspiration

Paul McCartney came up with the melody for “Eleanor Rigby” as he experimented on his piano. Donovan recalled hearing McCartney play an early version of the song on guitar, where the character was named Ola Na Tungee. At this point, the song reflected an Indian musical influence and its lyrics alluded to drug use, with references to “blowing his mind in the dark” and “a pipe full of clay”.

The name of the protagonist that McCartney initially chose was not Eleanor Rigby, but Miss Daisy Hawkins. In 1966, McCartney told Sunday Times journalist Hunter Davies how he got the idea for his song:

The first few bars just came to me. And I got this name in my head – “Daisy Hawkins picks up the rice in the church where a wedding has been.” I don’t know why … I couldn’t think of much more so I put it away for a day. Then the name “Father McCartney” came to me – and “all the lonely people”. But I thought people would think it was supposed to be my dad, sitting knitting his socks. Dad’s a happy lad. So I went through the telephone book and I got the name McKenzie.

McCartney said that the idea to call his character “Eleanor” was possibly because of Eleanor Bron, the actress who starred with the Beatles in their 1965 film Help! “Rigby” came from the name of a store in Bristol, Rigby & Evens Ltd. McCartney noticed the store while visiting his girlfriend of the time, actress Jane Asher, during her run in the Bristol Old Vic’s production of The Happiest Days of Your Life in January 1966. He recalled in 1984: “I just liked the name. I was looking for a name that sounded natural. ‘Eleanor Rigby’ sounded natural.”

In an October 2021 article in The New Yorker, McCartney wrote that his inspiration for “Eleanor Rigby” was an old lady who lived alone and whom he got to know very well. He would go shopping for her and sit in her kitchen listening to stories and her crystal radio set. McCartney said, “just hearing her stories enriched my soul and influenced the songs I would later write.”

Writing collaboration

McCartney wrote the melody and first verse alone, after which he presented the song to the Beatles when they were gathered in the music room of John Lennon’s home at Kenwood. Lennon, George Harrison, Ringo Starr and Lennon’s childhood friend Pete Shotton all listened to McCartney play his song through and contributed ideas. Harrison came up with the “Ah, look at all the lonely people” hook. Starr contributed the line “writing the words of a sermon that no one will hear” and suggested making “Father McCartney” darn his socks, which McCartney liked. It was then that Shotton suggested that McCartney change the name of the priest, in case listeners mistook the fictional character for McCartney’s own father.

McCartney could not decide how to end the song, and Shotton suggested that the two lonely people come together too late as Father McKenzie conducts Eleanor Rigby’s funeral. At the time, Lennon rejected the idea out of hand, but McCartney said nothing and used the idea, later acknowledging Shotton’s help. In Lennon’s recollection, the final touches were applied to the lyrics in the recording studio, at which point McCartney sought input from Neil Aspinall and Mal Evans, the Beatles’ longstanding road managers.

“Eleanor Rigby” serves as a rare example of Lennon subsequently claiming a more substantial role in the creation of a McCartney composition than is supported by others’ recollections. In the early 1970s, Lennon told music journalist Alan Smith that he wrote “about 70 per cent” of the lyrics, and in a letter to Melody Maker complaining about Beatles producer George Martin’s comments in a recent interview, he said that “Around 50 per cent of the lyrics were written by me at the studios and at Paul’s place.” In 1980, he recalled writing almost everything but the first verse. Shotton remembered Lennon’s contribution as being “virtually nil”, while McCartney said that “John helped me on a few words but I’d put it down 80–20 to me, something like that.” According to McCartney, “In My Life” and “Eleanor Rigby” are the only Lennon–McCartney songs where he and Lennon disagreed over their authorship.

In musicologist Walter Everett’s view, the lyric writing “likely was a group effort”. Historiographer Erin Torkelson Weber says that, from all the available accounts, McCartney was the principal author of the song and only Lennon’s post-1970 recollections contradict this. In the same 1980 interview, Lennon expressed his resentment at the way McCartney had sought their bandmates’ and friends’ creative input, rather than collaborate with Lennon directly. Lennon added, “That’s the kind of insensitivity he would have, which upset me in later years.” In addition to citing this emotional hurt, Weber suggests that the song’s critical acclaim may have motivated Lennon’s assertions, as he sought to portray himself as a greater musical genius than McCartney in the years following the Beatles’ break-up.

Composition – Music

The song is a prominent example of mode mixture, specifically between the Aeolian mode, also known as natural minor, and the Dorian mode. Set in E minor, the song is based on the chord progression Em–C, typical of the Aeolian mode and utilising notes ♭3, ♭6, and ♭7 in this scale. The verse melody is written in Dorian mode, a minor scale with the natural sixth degree. “Eleanor Rigby” opens with a C-major vocal harmony (“Aah, look at all …”), before shifting to E-minor (on “lonely people”). The Aeolian C-natural note returns later in the verse on the word “dre-eam” (C–B) as the C chord resolves to the tonic Em, giving an urgency to the melody’s mood.

The Dorian mode appears with the C# note (6 in the Em scale) at the beginning of the phrase “in the church”. The chorus beginning “All the lonely people” involves the viola in a chromatic descent to the 5th; from 7 (D natural on “All the lonely peo-“) to 6 (C♯ on “-ple”) to ♭6 (C on “they) to 5 (B on “from”). According to musicologist Dominic Pedler, this adds an “air of inevitability to the flow of the music (and perhaps to the plight of the characters in the song)”.

Composition – Lyrics

The lyrics represent a departure from McCartney’s previous songs, in their avoidance of first- and second-person pronouns and by diverging from the themes of a standard love song. The narrator takes the form of a detached onlooker, akin to a novelist or screenwriter. Beatles biographer Steve Turner says that this new approach reflects the likely influence of Ray Davies of the Kinks, specifically the latter’s singles “A Well Respected Man” and “Dedicated Follower of Fashion”.

Author Howard Sounes compares the song’s narrative to “the isolated broken figures” typical of a Samuel Beckett play, as Rigby dies alone, no mourners attend her funeral, and the priest “seems to have lost his congregation and faith”. In Everett’s view, McCartney’s description of Rigby and McKenzie elevates individuals’ loneliness and wasted lives to a universal level in the manner of Lennon’s autobiographical “Nowhere Man“. Everett adds that McCartney’s imagery is “vivid and yet common enough to elicit enormous compassion for these lost souls”.

Recording

“Eleanor Rigby” does not have a standard pop backing. None of the Beatles played instruments on it, although Lennon and Harrison did contribute harmony vocals. Like the earlier song “Yesterday“, “Eleanor Rigby” employs a classical string ensemble – in this case, an octet of studio musicians, comprising four violins, two violas and two cellos, all performing a score composed by George Martin. When writing the string arrangement, Martin drew inspiration from Bernard Herrmann’s work, particularly the latter’s score for the 1960 film Psycho.

Whereas “Yesterday” is played legato, “Eleanor Rigby” is played mainly in staccato chords with melodic embellishments. McCartney, reluctant to repeat what he had done on “Yesterday”, explicitly expressed that he did not want the strings to sound too cloying. For the most part, the instruments “double up” – that is, they serve as a single string quartet but with two instruments playing each of the four parts. Microphones were placed close to the instruments to produce a more biting and raw sound. Engineer Geoff Emerick was admonished by the string players saying “You’re not supposed to do that.” Fearing such close proximity to their instruments would expose the slightest deficiencies in their technique, the players kept moving their chairs away from the microphones until Martin got on the talk-back system and scolded: “Stop moving the chairs!” Martin recorded two versions, one with vibrato and one without, the latter of which was used. Lennon recalled in 1980 that “Eleanor Rigby” was “Paul’s baby, and I helped with the education of the child … The violin backing was Paul’s idea. Jane Asher had turned him on to Vivaldi, and it was very good.”

The octet was recorded on 28 April 1966, in Studio 2 at EMI Studios. The track was completed in Studio 3 on 29 April and on 6 June. Take 15 was selected as the master. The final overdub, on 6 June, was McCartney’s addition of the “Ah, look at all the lonely people” refrain over the song’s final chorus. This was requested by Martin, who said he came up with the idea of the line working contrapuntally to the chorus melody.

The original stereo mix had the lead vocal alone in the right channel during the verses, with the strings mixed to one channel, while the mono single and mono LP featured a more balanced mix. For the track’s inclusion on Yellow Submarine Songtrack in 1999, a new stereo mix was created that centres McCartney’s voice and spreads the string octet across the stereo image.

Release

On 5 August 1966, “Eleanor Rigby” was simultaneously released on a double A-side single, paired with “Yellow Submarine“, and on the album Revolver. In the LP sequencing, it appeared as the second track, between Harrison’s “Taxman” and Lennon’s “I’m Only Sleeping“. The Beatles thereby broke with their policy of ensuring that album tracks were not issued on their UK singles. According to a report in Melody Maker, the reason for this was to thwart sales of cover recordings of “Eleanor Rigby”. Harrison confirmed that they expected “dozens” of artists to have a hit with the song; however, he also said the track would “probably only appeal to Ray Davies types”. Writing in the 1970s, music critics Roy Carr and Tony Tyler described the motivation behind the single as a “growing dodge in the ever-innovative music industry”, building on UK record companies’ policy of reissuing an album’s most popular tracks, particularly those that had been culled for release as a single in the US, on a spin-off extended play.

The pairing of a ballad devoid of any instrumentation played by a Beatle and a novelty song marked a significant departure from the content of the band’s previous singles. Writing in his 1977 book The Beatles Forever, Nicholas Schaffner recalled that not only did the two sides have little in common with one another, but “‘Yellow Submarine’ was the most flippant and outrageous piece the Beatles would ever produce, [and] ‘Eleanor Rigby’ remains the most relentlessly tragic song the group attempted.” Unusually for their post-1965 singles also, the Beatles did not make a promotional film for either of the songs. Music historian David Simonelli groups “Eleanor Rigby” with “Taxman” and the band’s May 1966 single tracks “Paperback Writer” and “Rain” as examples of the Beatles’ “pointed social commentary” that consolidated their “dominance of London’s social scene”.

In the United States, the record’s release coincided with the group’s final tour and a public furore over the publication of Lennon’s remarks that the Beatles had become “more popular than Jesus Christ”; he also predicted the downfall of Christianity and described Christ’s disciples as “thick and ordinary”. In the US South, particularly, some radio stations refused to play the band’s music and organised public bonfires to burn Beatles records and memorabilia. Capitol Records were therefore wary of the religious references in “Eleanor Rigby” and promoted “Yellow Submarine” as the lead side. During the band’s first tour press conference, on 11 August, one reporter suggested that Father McKenzie’s sermons going unheard referred to the decline of religion in society. McCartney replied that the song was about lonely individuals, one of whom happened to be a priest.

The double A-side topped the Record Retailer chart (subsequently adopted as the UK Singles Chart) for four weeks, becoming their eleventh number-one single on the chart, and Melody Maker‘s chart for three weeks. It was also number 1 in Australia. The single topped charts in many other countries around the world, although “Yellow Submarine” was usually the listed side. In the US, disc jockeys began flipping the single midway through the tour as the radio boycotts were lifted. With each song eligible to chart separately there, “Eleanor Rigby” entered the Billboard Hot 100 in late August and peaked at number 11 for two weeks, and “Yellow Submarine” reached number 2.

Critical reception

[In “Eleanor Rigby”, the Beatles are] asking where all the lonely people come from and where they all belong as if they really want to know. Their capacity for fun has been evident since the beginning; their capacity for pity is something new and is a major reason for calling them artists.

– Dan Sullivan, The New York Times, March 1967

In Melody Maker‘s appraisal of Revolver, the writer described “Eleanor Rigby” as a “charming song” and one of the album’s best tracks. Derek Johnson, reviewing the single for the NME, said it lacked the immediate appeal of “Yellow Submarine” but “possess[ed] lasting value” and was “beautifully handled by Paul, with baroque-type strings”. Although he praised the string arrangement, Peter Jones of Record Mirror found the song “Pleasant enough but rather disjointed”, saying, “it’s commercial, but I like more meat from the Beatles.” Ray Davies offered an unfavourable view when invited to give a song-by-song rundown of Revolver in Disc and Music Echo. He dismissed “Eleanor Rigby” as a song designed “to please music teachers in primary schools”, adding: “I can imagine John saying, ‘I’m going to write this for my old schoolmistress.’ Still it’s very commercial.”

Reporting from London for The Village Voice, Richard Goldstein stated that Revolver was ubiquitous around the city, as if Londoners were uniting behind the Beatles in response to the antagonism shown towards the band in the US. He wrote: “As a commentary on the state of modern religion, this song will hardly be appreciated by those who see John Lennon as an anti-Christ. But ‘Eleanor Rigby’ is really about the unloved and un-cared-for.” Commenting on the lyrics, Edward Greenfield of The Guardian wrote, “There you have a quality rare in pop music, compassion, born of an artist’s ability to project himself into other situations.” He found this “Specific understanding of emotion” evident also in McCartney’s new love songs and described him as “the Beatle with the strongest musical staying power”. While bemoaning that Americans’ attention was overly focused on the band’s image and non-musical activities, KRLA Beat‘s album reviewer predicted that “Eleanor Rigby” would “become a contemporary classic”, adding that, aside from the quality of the string arrangement, “the haunting melody is one of the most beautiful to be found in our current pop music” and the lyrics “[are] both accurate and unforgettable”. Cash Box found the single’s pairing “unique” and described “Eleanor Rigby” as “a powerfully arranged, haunting story of sorrow and frustration”.

The NME chose “Eleanor Rigby” as its “Single of the Year” for 1966. Melody Maker included the song among the year’s five “singles to remember”, and Maureen Cleave of The Evening Standard recognised the single and Revolver as the year’s best records in her round-up of 1966. At the 9th Annual Grammy Awards in March 1967, “Eleanor Rigby” was nominated in three categories, winning the award for Best Contemporary (R&R) Vocal Performance, Male or Female for McCartney.

Appearance in Yellow Submarine film and subsequent releases

“Eleanor Rigby” appears in the Beatles’ 1968 animated film Yellow Submarine as the band’s submarine drifts over the desolate streets of Liverpool. Its poignancy ties in quite well with Starr (the first member of the group to encounter the submarine), who is represented as quietly bored and depressed. Starr’s character states: “Compared with my life, Eleanor Rigby’s was a gay, mad world.”[citation needed] Media theorist Stephanie Fremaux groups the song with “Only a Northern Song” and “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” as a scene that most clearly conveys the Beatles’ “aims as musicians”. In her description, the segment depicts “moments of color and hope in a land of conformity and loneliness”. With special effects directed by Charlie Jenkins, the animation incorporates photographs of silhouetted people; bankers with bowler hats and umbrellas are seen on rooftops, overlooking the streets.

The track also appears on several of the band’s greatest-hits compilations, including A Collection of Beatles Oldies, The Beatles 1962–1966 and 1. In 1986, “Yellow Submarine” / “Eleanor Rigby” was reissued in the UK as part of EMI’s twentieth anniversary of each of the Beatles’ singles and peaked at number 63 on the UK Singles Chart. The 2015 edition of 1 and the expanded 1+ box set includes a video clip for the song, taken from the Yellow Submarine film.

In 1996, a stereo remix of Martin’s isolated string arrangement was released on the Beatles’ Anthology 2 outtakes compilation. For the song’s inclusion on the Love album in 2006, a new mix was created that adds a strings-only portion at the start of the track and closes with a transition featuring part of Lennon’s acoustic guitar from the 1968 song “Julia“.

The real-life Eleanor Rigby

McCartney’s recollection of how he chose the name of his protagonist came under scrutiny in the 1980s, after a headstone engraved with the name “Eleanor Rigby” was discovered in the graveyard of St Peter’s Parish Church in Woolton, in Liverpool. Part of a well-known local family, Rigby had died in 1939 at the age of 44. Close by was a headstone bearing the name McKenzie. St Peter’s was where Lennon attended Sunday school as a boy, and he and McCartney first met at the church fete there in July 1957. McCartney has said that while he often walked through the churchyard, he had no recollection of ever seeing Rigby’s grave. He attributed the coincidence to a product of his subconscious. McCartney has also dismissed claims by people who, because of their name and a tenuous association with the Beatles, believed they were the real Father McKenzie.

In 1990, McCartney responded to a request from Sunbeams Music Trust by donating a historical document that listed the wages paid by Liverpool City Hospital; among the employees listed was Eleanor Rigby, who worked as a scullery maid at the hospital. Dating from 1911 and signed by the 16-year-old Rigby, the document attracted interest from collectors because of what it seemingly revealed about the inspiration behind the Beatles song. It sold at auction in November 2008 for £115,000. McCartney stated at the time: “Eleanor Rigby is a totally fictitious character that I made up … If someone wants to spend money buying a document to prove a fictitious character exists, that’s fine with me.”

Rigby’s grave in Woolton became a landmark for Beatles fans visiting Liverpool. A digitised image of the headstone was added to the 1995 music video for the Beatles’ reunion song “Free as a Bird“. Continued interest in a possible connection between the real-life Eleanor Rigby and the 1966 song led to the deeds for the grave being put up for auction in 2017, along with a Bible that once belonged to Rigby and a handwritten score for the track (subsequently withdrawn) and other items of Beatles memorabilia.

Legacy

Sociocultural impact and literary appreciation

Although “Eleanor Rigby” was far from the first pop song to deal with death and loneliness, according to Ian MacDonald it “came as quite a shock to pop listeners in 1966”. It took a bleak message of depression and desolation, written by a famous pop group, with a sombre, almost funeral-like backing, to the number one spot of the pop charts. Richie Unterberger of AllMusic cites the song’s focus on “the neglected concerns and fates of the elderly” as “just one example of why the Beatles’ appeal reached so far beyond the traditional rock audience”.

In its inclusion of compositions that departed from the format of standard love songs, Revolver marked the start of a change in the Beatles’ core audience, as their young, female-dominated fanbase gave way to a following that increasingly comprised more serious-minded, male listeners. Commenting on the preponderance of young people who, under the influence of drugs such as marijuana and LSD, increasingly afforded films and rock music exhaustive analysis, Mark Kurlansky writes: “Beatles songs were examined like Tennyson’s poems. Who was Eleanor Rigby?”

The song’s lyrics became the subject of study by sociologists, who from 1966 began to view the band as spokesmen for their generation. In 2018, Colin Campbell, professor of sociology at the University of York, published a book-length analysis of the lyrics, titled The Continuing Story of Eleanor Rigby. Writing in the 1970s, however, Roy Carr and Tony Tyler dismissed the song’s sociological relevance as academics “rear[ing] a mis-shapen skull”, adding: “Though much praised at the time (by sociologists), ‘Eleanor Rigby’ was sentimental, melodramatic and a blind alley.”

According to author and satirist Craig Brown, the lyrics to “Eleanor Rigby” have been “the most extravagantly praised” of all the Beatles’ songs, “and by all the right people”. These include poets such as Allen Ginsberg and Thom Gunn, the last of whom likened the song to W.H. Auden’s poem “Miss Gee”, and literary critic Karl Miller, who included the lyrics in his 1968 anthology Writing in England Today.

In his 1970 book Revolt in Style, Liverpudlian musician and critic George Melly admired the “imaginative truth of ‘Eleanor Rigby'”, likening it to author James Joyce’s treatment of his own hometown in Dubliners. Novelist and poet A.S. Byatt recognised the song as having the “minimalist perfection” of a Samuel Beckett story. In a talk on BBC Radio 3 in 1993, Byatt said that “Wearing a face that she keeps in a jar by the door” – a line that MacDonald deems “the single most memorable image in The Beatles’ output” – conveys a level of despair unacceptable to English middle-class sensibilities and, rather than being a reference to make-up, suggests that Rigby “is faceless, is nothing” once alone in her home.

In 1982, the Eleanor Rigby statue was unveiled on Stanley Street in Liverpool as a donation from Tommy Steele in tribute to the Beatles. The plaque carries a dedication to “All the Lonely People”.

In 2004, Revolver appeared second in The Observer‘s list of “The 100 Greatest British Albums”, compiled by a panel of 100 contributors. In his commentary for the newspaper, John Harris highlighted “Eleanor Rigby” as arguably the album’s “single greatest achievement”, saying that it “perfectly evokes an England of bomb sites and spinsters, where in the darkest moments it does indeed seem that ‘no one was saved'”. Harris concluded: “Most pop songwriters have always wrapped up Englishness in camp and irony – here, in a rare moment for British rock, post-war Britain is portrayed in terms of its truly grave aspects.”

Musical influence and further recognition

David Simonelli cites the chamber-orchestrated “Eleanor Rigby” as an example of the Beatles’ influence being such that, whatever the style of song, their progressiveness defined the parameters of rock music. Music academics Michael Campbell and James Brody highlight the track’s melodic shape and imaginative backing to illustrate how, paired with similarly synergistic elements in “A Day in the Life“, the Beatles’ use of music and lyrics made them one of the two acts in 1960s rock, along with Bob Dylan, who were “most responsible for elevating its level of discourse and expanding its horizons”.

Soon after its release, Melly stated that “Pop has come of age” with “Eleanor Rigby”, while songwriter Jerry Leiber said, “I don’t think there’s ever been a better song written.” In a 1967 interview, Pete Townshend of the Who commented on the Beatles: “They are basically my main source of inspiration – and everyone else’s for that matter. I think ‘Eleanor Rigby’ was a very important musical move forward. It certainly inspired me to write and listen to things in that vein.” In his television show Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution, which aired in April 1967, American composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein championed the Beatles’ talents among contemporary pop acts and highlighted the song’s string arrangement as an example of the eclectic qualities that made 1960s pop music worthy of recognition as art. Barry Gibb of the Bee Gees said that their 1969 song “Melody Fair” was influenced by “Eleanor Rigby”. America’s single “Lonely People” was written by Dan Peek in 1973 as an optimistic response to the Beatles track.

In 2000, Mojo ranked “Eleanor Rigby” at number 19 on the magazine’s list of “The 100 Greatest Songs of All Time”. In BBC Radio 2’s millennium poll, listeners voted it as one of the top 100 songs of the twentieth century. It was ranked at number 137 on Rolling Stone‘s list “The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time” in 2004, and number 243 on the 2021 revised list. “Eleanor Rigby” was inducted into the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences’ Grammy Hall of Fame in 2002. Based on its appearances in professional rankings and listings, the aggregate website Acclaimed Music lists “Eleanor Rigby” as the 186th most acclaimed song in history. It has been a Desert Island Discs selection by individuals such as Cathy Berberian, Charles Aznavour, Patricia Hayes, Carlos Frank and Geoffrey Howe.

Other versions

By the mid 2000s, over 200 cover versions of “Eleanor Rigby” had been made. George Martin included the song on his November 1966 album George Martin Instrumentally Salutes “The Beatle Girls”, one of a series of interpretive works by the band’s producer designed to appeal to the easy listening market. […]

McCartney recorded a new version of “Eleanor Rigby”, with Martin again scoring the orchestration, for his 1984 film Give My Regards to Broad Street. Departing from the premise of the film, the song’s sequence features McCartney dressed in Victorian costume. On the accompanying soundtrack album, the track segues into a symphonic extension titled “Eleanor’s Dream”. He has also performed the song frequently in concert, starting with his 1989–90 world tour. […]

I wrote it at the piano, just vamping an E minor chord; letting that stay as a vamp and putting a melody over it, just danced over the top of it. It has almost Asian Indian rhythms.

Paul McCartney – From Many Years From Now by, 1997

I was sitting at the piano when I thought of it. The first few bars just came to me, and I got this name in my head… Daisy Hawkins picks up the rice in the church. I don’t know why. I couldn’t think of much more so I put it away for a day. Then the name Father McCartney came to me, and all the lonely people. But I thought that people would think it was supposed to be about my Dad sitting knitting his socks. Dad’s a happy lad. So I went through the telephone book and I got the name McKenzie. I was in Bristol when I decided Daisy Hawkins wasn’t a good name. I walked ’round looking at the shops, and I saw the name Rigby. Then I took the song down to John’s house in Weybridge. We sat around, laughing, got stoned and finished it off.

Paul McCartney – Interview with Sunday Times, September 1966

To be honest it wasn’t until I heard ‘Eleanor Rigby’ ‘She keeps her face in a jar by the door’ that I became aware that your songs had a lot more to offer than ‘Yea Yea Yea’. Perhaps we could talk about this for a start?

Well that started off with sitting down at the piano and getting the first line of the melody, and playing around with words. I think it was ‘Miss Daisy Hawkins’ originally; then it was her picking up the rice in a church after a wedding. That’s how nearly all our songs start, with the first line just suggesting itself from books or newspapers.

At first I thought it was a young Miss Daisy Hawkins, a bit like ‘Annabel Lee’, but not so sexy; but then I saw I’d said she was picking up the rice in church, so she had to be a cleaner; she had missed the wedding, and she was suddenly lonely. In fact she had missed it all — she was the spinster type.

Jane (Jane Asher) was in a play in Bristol then, and I was walking round the streets waiting for her to finish. I didn’t really like ‘Daisy Hawkins’ — I wanted a name that was more real. The thought just came: ‘Eleanor Rigby picks up the rice and lives in a dream’ — so there she was. The next thing was Father Mackenzie. It was going to be Father McCartney, but then I thought that was a bit of a hang-up for my Dad, being in this lonely song. So we looked through the phone book. That’s the beauty of working at random — it does come up perfectly, much better than if you try to think it with your intellect.

Anyway, there was Father Mackenzie, and he was just as I had imagined him, lonely, darning his socks. We weren’t sure if the song was going to go on. In the next verse we thought of a Bin man, an old feller going through dustbins; but it got too involved — embarrassing. John and I wondered whether to have Eleanor Rigby and him have a thing going, but we couldn’t really see how. When I played it to John we decided to finish it.

That was the point anyway. She didn’t make it, she never made it with anyone, she didn’t even look as if she was going to.

Paul McCartney – Interview with The Observer, November 1967

I can hear a whole song in one chord. In fact, I think you can hear a whole song in one note, if you listen hard enough. But nobody ever listens hard enough. OK, so that’s the Joan of Arc bit. I couldn’t think of much more, so I put it away for a day. Then the name Father McCartney came to me, and all the lonely people. But I thought people would think it was supposed to be my dad, sitting knitting his socks. Dad’s a happy lad, so I went through the telephone book and I got the name McKenzie. I was walking round Bristol one night (January 1966), waiting for Jane Asher, who was acting at the Old Vic* , when I decided that Daisy Hawkins wasn’t a good name. I wanted a really nice name that didn’t sound wrong. It had to sound like someone’s name, but different enough and wasn’t just Valerie Higgins, you know. It had to be a little more evocative. So, I walked round looking at the shops and I saw the great name Rigby, which was normal, but it’s got a little extra thing to it. Then I had Eleanor, and worked with that. Then I took it down to John’s house in Weybridge. We sat around, laughing, got stoned and finished it off. It all sort of flowed from there.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles: Off The Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

The first verse was his and the rest are basically mine. He knew he had a song but, by that time, he didn’t want to ask for my help, and we were sitting around with Mal Evans and Neil Aspinall, so he said to us, ‘Hey, you guys, finish up the lyrics.’ I was there with Mal and Neil and I was insulted and hurt that Paul had just thrown it out in the air. He actually meant he wanted me to do it, and, of course, there isn’t a line of their’s in the song, because I finally went off to a room with Paul and we finished the song.

John Lennon – From “The Beatles: Off The Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

Most of the song was written in John’s music room at his house in Kenwood, during one of my weekend visits. The other three Beatles and their wives had come over for dinner, and after which, we all gathered around the television in Cyn’s beloved library. This particular night, John grew bored with the TV programme. ‘Fuck this shit,’ he said. ‘Let’s go upstairs and play a bit of music.’ Paul, George and Ringo duly followed John upstairs to a room adjoining his little recording studio. Paul, as always, had brought along his guitar, which he got out and began strumming. ‘I’ve got this little tune here,’ he said. ‘It keeps popping into me head, but I haven’t got very far with it.’ Then he sang the beginning of ‘Eleanor Rigby’. We all sat around, making suggestions, throwing out the odd line or phrase, all of us, that is, except for the Beatle who had proposed the session in the first place.

Then Paul got to the verse about the cleric, whose name he had down as Father McCartney. Ringo came up with the line about ‘Father McCartney darning his socks in the night,’ which everybody liked. ‘Hang on a minute, Paul.’ I said. ‘People are going to think that’s your poor old dad, left all alone in Liverpool to darn his own socks.’ ‘Oh shit!’ he laughs. ‘I never thought of that. We’d better change the name. What shall we call him then?’ I then noticed a telephone directory lying around, and said, ‘Give us that phone book. I’ll have a look through the Macs.’

One name that particularly amused us was McVicar, but it didn’t quite seem to flow with the line when Paul sang it. So, I asked him to try Father McKenzie out for size, and everyone appeared to like the lilt of it. After we tinkered with a few more phrases, Paul said, ‘The real trouble is I’ve no idea how to finish this song.’ I said, ‘Why don’t you have Eleanor Rigby dying and have Father McKenzie doing the burial service for her? That way you’d have the two lonely people coming together in the end, but too late.’

John then piped in with his first comment of the entire session, ‘I don’t think you understand what we’re trying to get at, Pete.’ All I could think of to say was, ‘Fuck you, John.’ Paul packed his guitar away, and we all wandered out of the room. Even after George produced a joint to lighten up the mood, I continued to feel more than a bit uptight about John’s unwarranted sarcasm. Maybe my great suggestion hadn’t been so great after all.

Pete Shotton – From “The Beatles: Off The Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

I wrote that. I got the name Rigby from a shop in Bristol. I was wandering round Bristol one day and saw a shop called Rigby.. And I think Eleanor was from Eleanor Bron, the actress we worked with in the film Hep! . But I just liked the name. I was looking for a name that sounded natural. Eleanor Rigby sounded natural.

Paul McCartney – Interview with Playboy Magazine, 1984

Later, when I’d written ‘Eleanor Rigby’, I tried learning [how to write our music] with a proper bloke from the Guildhall School of Music whom I was put on to by Jane Asher’s mum (Margaret Elliot, an oboe teacher). But I didn’t get on with him either. I went off him when I showed him ‘Eleanor Rigby’ because I thought he’d be interested, and he wasn’t. I thought he’d be intrigued by the little time jumps.

I wrote ‘Eleanor Rigby’ when I was living in London and had a piano in the basement. I used to disappear there and have a fiddle around, and while I was fiddling on a chord some words came out: ‘Dazzie-de-da-zu picks up the rice in the church where a wedding has been…’ This idea of someone picking up rice after a wedding took it in that poignant direction, into a ‘lonely people’ direction.

I had a bit of trouble with the name, and I’m always keen to get a name that sounds right. Looking at my old school photographs I remembered the names, and they all work: James Stringfellow, Grace Pendleton. Whereas when you read novels, it’s all ‘James Turnbury’ and it’s not real. So I was very keen to get a real-sounding name for that tune and the whole idea.

We were working with Eleanor Bron on Help! and I liked the name Eleanor; it was the first time I’d ever been involved with that name. I saw ‘Rigby’ on a shop in Bristol when I was walking round the city one evening. I thought, ‘Oh, great name, Rigby.’ It’s real, and yet a little bit exotic. So it became ‘Eleanor Rigby’.

I thought, I swear, that I made up the name Eleanor Rigby like that. I remember quite distinctly having the name Eleanor, looking around for a believable surname and then wandering around the docklands in Bristol and seeing the shop there. But it seems that up in Woolton Cemetery, where I used to hang out a lot with John, there’s a gravestone to an Eleanor Rigby. Apparently, a few yards to the right there’s someone called McKenzie.

It was either complete coincidence or in my subconscious. I suppose it was more likely in my subconscious, because I will have been amongst those graves knocking around with John and wandering through there. It was the sort of place we used to sunbathe, and we probably had a crafty fag in the graveyard. So subconscious it may be – but this is just bigger than me. I don’t know the answer to that one. Coincidence is just a word that says two things coincided. We rely on it as an explanation, but it is actually just names it – it goes no further than that. But as to why they happen together, there are probably far deeper reasons than our little brains can grasp.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

I know George (Harrison) was there when we came up with ‘Ah, look at all the lonely people.’ He (Paul) and George were settling on that as I left the studio to go to the toilet, and I heard the lyric and turned around and said, ‘That’s it!’ The violin backing was Paul’s idea. Jane Asher had turned him on to Vivaldi and it was very good. The violins were straight out of Vivaldi. I can’t take any credit for that, at all.

John Lennon – From “The Beatles: Off The Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

I thought of the backing but it was George Martin who finished it off. I just go bash, bash on the piano. He knows what I mean.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles: Off The Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

‘Eleanor Rigby’ was done very much on the lines of ‘Yesterday’. Paul came round to my flat one day and he played the piano and I played the piano, and I took a note of his music. There is also an octet on the record, made up of four violins, two violas and two cellos.

Geroge Martin – From “The Beatles: Off The Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

My mum’s favorite cold cream was Nivea, and I love it to this day. That’s the cold cream I was thinking of in the description of the face Eleanor keeps “in a jar by the door.” I was always a little scared by how often women used cold cream.

Growing up, I knew a lot of old ladies—partly through what was called Bob-a-Job Week, when Scouts did chores for a shilling. You’d get a shilling for cleaning out a shed or mowing a lawn. I wanted to write a song that would sum them up. Eleanor Rigby is based on an old lady that I got on with very well. I don’t even know how I first met “Eleanor Rigby,” but I would go around to her house, and not just once or twice. I found out that she lived on her own, so I would go around there and just chat, which is sort of crazy if you think about me being some young Liverpool guy. Later, I would offer to go and get her shopping. She’d give me a list and I’d bring the stuff back, and we’d sit in her kitchen. I still vividly remember the kitchen, because she had a little crystal-radio set. That’s not a brand name; it actually had a crystal inside it. Crystal radios were quite popular in the nineteen-twenties and thirties. So I would visit, and just hearing her stories enriched my soul and influenced the songs I would later write.

Paul McCartney – From “The Lyrics” book – From Paul McCartney on Writing “Eleanor Rigby” | The New Yorker, 2021

So my life is full of these happy accidents, and, coming back to where the name Eleanor Rigby comes from, my memory has me visiting Bristol, where Jane Asher was playing at the Old Vic. I was wandering around, waiting for the play to finish, and saw a shop sign that read “Rigby,” and I thought, That’s it! It really was as happenstance as that. When I got back to London, I wrote the song in Mrs. Asher’s music room in the basement of 57 Wimpole Street, where I was living at the time.

Paul McCartney – From “The Lyrics” book – From Paul McCartney on Writing “Eleanor Rigby” | The New Yorker, 2021

When I started working on the words in earnest, “Eleanor” was always part of the equation, I think, because we had worked with Eleanor Bron on the film “Help!” and we knew her from the Establishment, Peter Cook’s club, on Greek Street. I think John might have dated her for a short while, too, and I liked the name very much. Initially, the priest was “Father McCartney,” because it had the right number of syllables. I took the song to John at around that point, and I remember playing it to him, and he said, “That’s great, Father McCartney.” He loved it. But I wasn’t really comfortable with it, because it’s my dad—my father McCartney—so I literally got out the phone book and went on from “McCartney” to “McKenzie.”

Paul McCartney – From “The Lyrics” book – From Paul McCartney on Writing “Eleanor Rigby” | The New Yorker, 2021

George Martin had introduced me to the string-quartet idea through “Yesterday.” I’d resisted the idea at first, but when it worked I fell in love with it. So I ended up writing “Eleanor Rigby” with a string component in mind. When I took the song to George, I said that, for accompaniment, I wanted a series of E-minor chord stabs. In fact, the whole song is really only two chords: C major and E minor. In George’s version of things, he conflates my idea of the stabs and his own inspiration by Bernard Herrmann, who had written the music for the movie “Psycho.” George wanted to bring some of that drama into the arrangement. And, of course, there’s some kind of madcap connection between Eleanor Rigby, an elderly woman left high and dry, and the mummified mother in “Psycho.”

Paul McCartney – From “The Lyrics” book – From Paul McCartney on Writing “Eleanor Rigby” | The New Yorker, 2021

Paul’s baby, and I helped with the education of the child… The violin backing was Paul’s idea. Jane Asher had turned him on to Vivaldi, and it was very good.

John Lennon, 1980

One quiet Sunday I was alone, recording new songs on my little Uher tape machine, when the doorbell rang. It was Paul on his own. He played a couple of tunes to me on his Martin Acoustic six string. One sang of a strange chap called:

Ola Na Tungee,

Blowing his mind in the dark with a pipe full of clay —

No one can say…The tune was “Eleanor Rigby” but the words had not all come out yet. Songwriters sometimes sketch in the lyric with any old line, then come back to it.

Donovan – From “The Autobiography of Donovan: The Hurdy Gurdy Man“, 2007

Paul has always thought that he came up with the name Eleanor because of having worked with Eleanor Bron in the film Help! but I am convinced that he took the name from a gravestone in a cemetery close to Wimbledon Common where we were both walking. The name on this gravestone was Eleanor Bygraves and Paul thought the name fitted the song. He then came back to my office and began playing it on my clavichord.

Lionel Bart – Songwriter – From “The Beatles: Off The Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

From The Usenet Guide to Beatles Recording Variations:

[a] mono 22 Jun 1966.

UK: Parlophone R5489 single 1966, Parlophone PMC 7009 Revolver 1966, Parlophone PMC 7016 Collection of Oldies 1966.

US: Capitol 5715 single 1966, T2576 Revolver 1966.

CD: EMI single 1989.[b] stereo 22 Jun 1966.

UK: Parlophone PCS 7009 Revolver 1966, Parlophone PCS 7016 Collection of Oldies 1966, Apple PCSP 717 The Beatles 1962-1966 1973.

US: Capitol ST 2576 Revolver 1966, Apple SKBO-3403 The Beatles 1962-1966 1973.

CD: EMI CDP 7 46441 2 Revolver 1987, EMI CDP 7 97036 2 The Beatles 1962-1966 1993.[c] stereo 1995.

CD: Apple CDP 8 34448 2 Anthology 2 1996.The ADT in stereo [b] continues into “Elean” in 1st verse, a really glaring mistake. The lead vocal, perhaps too prominent in both [a] and [b], sounds stronger in mono [a].

The Anthology mix [c] omits the vocals, and remixes the string tracks.

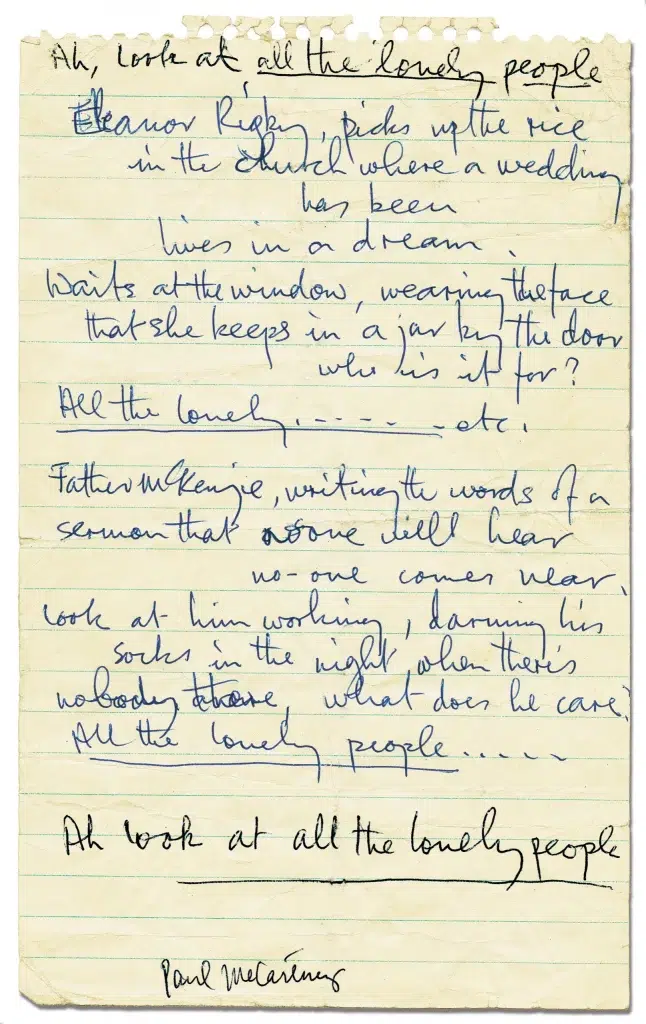

Ah look at all the lonely people

Ah look at all the lonely people

Eleanor Rigby, picks up the rice

In the church where a wedding has been

Lives in a dream

Waits at the window, wearing the face

That she keeps in a jar by the door

Who is it for

All the lonely people

Where do they all come from?

All the lonely people

Where do they all belong?

Father McKenzie, writing the words

Of a sermon that no one will hear

No one comes near

Look at him working, darning his socks

In the night when there's nobody there

What does he care

All the lonely people

Where do they all come from?

All the lonely people

Where do they all belong?

Ah look at all the lonely people

Ah look at all the lonely people

Eleanor Rigby, died in the church

And was buried along with her name

Nobody came

Father McKenzie, wiping the dirt

From his hands as he walks from the grave

No one was saved

All the lonely people

Where do they all come from?

All the lonely people

Where do they all belong?

Yellow Submarine / Eleanor Rigby (UK)

7" Single • Released in 1966

2:07 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Vocals John Lennon : Harmony vocals George Harrison : Harmony vocals George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Tony Gilbert : Violin Sidney Sax : Violin John Sharpe : Violin Jürgen Hess : Violin Stephen Shingles : Viola John Underwood : Viola Derek Simpson : Cello Norman Jones : Cello

Session Recording: Apr 28, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Apr 29, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jun 06, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Jun 22, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Yellow Submarine / Eleanor Rigby (US)

7" Single • Released in 1966

2:07 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Vocals John Lennon : Harmony vocals George Harrison : Harmony vocals George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Tony Gilbert : Violin Sidney Sax : Violin John Sharpe : Violin Jürgen Hess : Violin Stephen Shingles : Viola John Underwood : Viola Derek Simpson : Cello Norman Jones : Cello

Session Recording: Apr 28, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Apr 29, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jun 06, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Jun 22, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

LP • Released in 1966

2:07 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Vocals John Lennon : Harmony vocals George Harrison : Harmony vocals George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Tony Gilbert : Violin Sidney Sax : Violin John Sharpe : Violin Jürgen Hess : Violin Stephen Shingles : Viola John Underwood : Viola Derek Simpson : Cello Norman Jones : Cello

Session Recording: Apr 28, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Apr 29, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jun 06, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Jun 22, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

LP • Released in 1966

2:07 • Studio version • B • Stereo

Paul McCartney : Vocals John Lennon : Harmony vocals George Harrison : Harmony vocals George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Tony Gilbert : Violin Sidney Sax : Violin John Sharpe : Violin Jürgen Hess : Violin Stephen Shingles : Viola John Underwood : Viola Derek Simpson : Cello Norman Jones : Cello

Session Recording: Apr 28, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Apr 29, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jun 06, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Jun 22, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Revolver (UK Mono - first pressing)

LP • Released in 1966

2:07 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Vocals John Lennon : Harmony vocals George Harrison : Harmony vocals George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Tony Gilbert : Violin Sidney Sax : Violin John Sharpe : Violin Jürgen Hess : Violin Stephen Shingles : Viola John Underwood : Viola Derek Simpson : Cello Norman Jones : Cello

Session Recording: Apr 28, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Apr 29, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jun 06, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Jun 22, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

LP • Released in 1966

2:10 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Vocals John Lennon : Harmony vocals George Harrison : Harmony vocals George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Tony Gilbert : Violin Sidney Sax : Violin John Sharpe : Violin Jürgen Hess : Violin Stephen Shingles : Viola John Underwood : Viola Derek Simpson : Cello Norman Jones : Cello

Session Recording: Apr 28, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Apr 29, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jun 06, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Jun 22, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

LP • Released in 1966

2:08 • Studio version • B • Stereo

Paul McCartney : Vocals John Lennon : Harmony vocals George Harrison : Harmony vocals George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Tony Gilbert : Violin Sidney Sax : Violin John Sharpe : Violin Jürgen Hess : Violin Stephen Shingles : Viola John Underwood : Viola Derek Simpson : Cello Norman Jones : Cello

Session Recording: Apr 28, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Apr 29, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jun 06, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Jun 22, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

A Collection of Beatles Oldies (Mono)

LP • Released in 1966

2:02 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Vocals John Lennon : Harmony vocals George Harrison : Harmony vocals George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Tony Gilbert : Violin Sidney Sax : Violin John Sharpe : Violin Jürgen Hess : Violin Stephen Shingles : Viola John Underwood : Viola Derek Simpson : Cello Norman Jones : Cello

Session Recording: Apr 28, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Apr 29, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jun 06, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Jun 22, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

A Collection of Beatles Oldies (Stereo)

LP • Released in 1966

2:02 • Studio version • B • Stereo

Paul McCartney : Vocals John Lennon : Harmony vocals George Harrison : Harmony vocals George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Tony Gilbert : Violin Sidney Sax : Violin John Sharpe : Violin Jürgen Hess : Violin Stephen Shingles : Viola John Underwood : Viola Derek Simpson : Cello Norman Jones : Cello

Session Recording: Apr 28, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Apr 29, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jun 06, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Jun 22, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Official album • Released in 1973

2:02 • Studio version • B

Paul McCartney : Vocals John Lennon : Harmony vocals George Harrison : Harmony vocals George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Tony Gilbert : Violin Sidney Sax : Violin John Sharpe : Violin Jürgen Hess : Violin Stephen Shingles : Viola John Underwood : Viola Derek Simpson : Cello Norman Jones : Cello

Session Recording: Apr 28, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Apr 29, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jun 06, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Jun 22, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Unofficial live

2:34 • Live

Concert From the concert in Hamburg, Germany on Oct 03, 1989

Driving USA Super Tree Volume 13 - Uniondale, NY 21 April 2002

Unofficial live

2:56 • Live

Concert From the concert in Uniondale, USA on Apr 21, 2002

Live at The Palace - Auburn Hills, Detroit MI May 1, 2002

Unofficial live

2:43 • Live

Concert From the concert in Detroit, USA on May 01, 2002

Stockholm Globe Arena, May 4, 2003

Unofficial live

2:48 • Live

Concert From the concert in Stockholm, Sweden on May 04, 2003

2022 • For The Beatles

Concert Dec 02, 2009 in Hamburg

Concert Dec 03, 2009 in Berlin

Concert Mar 28, 2010 in Phoenix

Concert Nov 21, 2010 in Sao Paulo

Concert Dec 13, 2010 in New York

Concert May 06, 2013 in Goiania

Concert May 09, 2013 in Fortaleza

Concert Jul 05, 2014 in Albany

“Eleanor Rigby” has been played in 523 concerts and 1 soundchecks.

Los Angeles • Dodgers Stadium • USA

Jul 13, 2019 • Part of Freshen Up Tour

Jul 10, 2019 • Part of Freshen Up Tour

Jul 06, 2019 • Part of Freshen Up Tour

Las Vegas • T Mobile Arena • USA

Jun 29, 2019 • Part of Freshen Up Tour

Las Vegas • T Mobile Arena • USA

Jun 28, 2019 • Part of Freshen Up Tour

The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present

"Eleanor Rigby" is one of the songs featured in the book "The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present," published in 2021. The book explores Paul McCartney's early Liverpool days, his time with the Beatles, Wings, and his solo career. It pairs the lyrics of 154 of his songs with his first-person commentary on the circumstances of their creation, the inspirations behind them, and his current thoughts on them.

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.