UK Release date : Thursday, June 1, 1967

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (UK Mono)

By The Beatles • LP • Part of the collection “The Beatles • The original UK LPs”

Last updated on January 29, 2024

UK Release date : Thursday, June 1, 1967

By The Beatles • LP • Part of the collection “The Beatles • The original UK LPs”

Last updated on January 29, 2024

Previous album Mar 01, 1967 • "Mellow Yellow" by Donovan released in the US

Article June 1967 • Ads for Indica Books co-drawn by Paul McCartney published in 'International Times'

Session Jun 01, 1967 • Jamming

Album Jun 01, 1967 • "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (UK Mono)" by The Beatles released in the UK

Album Jun 01, 1967 • "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (UK Stereo)" by The Beatles released in the UK

Album Jun 01, 1967 • "Back In The U.S.S.R. / Twist And Shout" by Paul McCartney released in the UK

This album was recorded during the following studio sessions:

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

2:03 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Backing vocals, Bass, Electric guitar, Lead vocals Ringo Starr : Drums John Lennon : Backing vocals George Harrison : Backing vocals, Electric guitar George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Neill Sanders : French horn James W. Buck : French horn Tony Randall : French horn John Burden : French horn

Session Recording: Feb 01, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Feb 02, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Mar 03 & 06, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Mar 06, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

With A Little Help From My Friends

2:44 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Backing vocals, Bass, Piano, Timpani Ringo Starr : Drums, Lead vocals, Tambourine John Lennon : Backing vocals, Cowbell George Harrison : Backing vocals, Lead guitar George Martin : Hammond organ, Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Mar 29, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Mar 30, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Mar 31, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

3:29 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Backing vocals, Bass, Lowrey organ Ringo Starr : Drums John Lennon : Lead vocals George Harrison : Acoustic guitar, Lead guitar, Tamboura George Martin : Piano, Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Mar 01, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Mar 02, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Mar 03, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

2:48 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Bass, Lead vocals, Pianet electric piano Ringo Starr : Congas, Drums John Lennon : Backing vocals, Electric guitar George Harrison : Backing vocals, Electric guitar, Tamboura George Martin : Pianet electric piano (?), Piano, Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Malcolm Addey : Recording engineer Ken Townsend : Recording engineer Peter Vince : Recording engineer Unknown musician(s) : Handclaps

Session Recording: Mar 09, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Mar 10, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Mar 23, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Mar 23, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

2:37 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Bass, Lead vocals Ringo Starr : Drums John Lennon : Backing vocals, Maracas George Harrison : Backing vocals, Electric guitar George Martin : Harpsichord, Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Adrian Ibbetson : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Feb 09, 1967 • Studio Regent Sound Studio, London

Session Overdubs: Feb 21, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Feb 21, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

3:35 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Lead vocals John Lennon : Lead vocals George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Stephen Shingles : Viola John Underwood : Viola Erich Gruenberg : Violin Derek Jacobs : Violin Trevor Williams : Violin José Luis Garcia : Violin Dennis Vigay : Cello Alan Dalziel : Cello Gordon Pearce : Double bass Sheila Bromberg : Harp

Session Recording: Mar 17, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Mar 20, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Mar 20, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Being For The Benefit of Mr. Kite!

2:38 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Backing vocals, Bass, Electric guitar Ringo Starr : Bass harmonica (?), Drums, Tambourine John Lennon : Lead vocals, Lowrey organ George Harrison : Backing vocals, Bass harmonica, Tambourine George Martin : Glockenspiel, Harmonium, Lowrey organ, Producer, Sound effects Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer, Sound effects Mal Evans : Bass harmonica Neil Aspinall : Bass harmonica

Session Recording: Feb 17, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Feb 20, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: March 28, 29 & 31, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Mar 31, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Written by George Harrison

5:05 • Studio version • A • Mono

George Harrison : Acoustic guitar, Lead vocals, Sitar, Tamboura George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Jack Rothstein : Violin Neil Aspinall : Tamboura Ralph Elman : Violin Jack Greene : Violin Erich Gruenberg : Violin Alan Loveday : Violin Julien Gaillard : Violin Paul Scherman : Violin David Wolfsthal : Violin Reginald Kilbey : Cello Allen Ford : Cello Peter Beavan : Cello Unknown musician(s) : Swarmandal Anna Joshi : Dilruba Amrit Gajjar : Dilruba Natwar Soni : Tabla Buddhadev Kansara : Tamboura

Session Recording: Mar 15, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Mar 22, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Apr 03, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio One, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Apr 04, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

2:38 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Backing vocals, Bass, Lead vocals, Piano Ringo Starr : Chimes, Drums John Lennon : Backing vocals, Electric guitar George Harrison : Backing vocals George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Robert Burns : Clarinet Henry MacKenzie : Clarinet Frank Reidy : Clarinet

Session Recording: Dec 06, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Dec 08, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Dec 20 & 21, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Dec 30, 1966 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

2:42 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Backing vocals, Bass, Comb and paper (?), Lead vocals, Piano Ringo Starr : Backing vocals, Comb and paper (?), Drums John Lennon : Acoustic guitar, Backing vocals, Comb and paper (?) George Harrison : Acoustic guitar, Backing vocals, Comb and paper (?) George Martin : Piano, Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Feb 23, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Feb 24, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Mar 07 & 21, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Mar 21, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

2:41 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Backing vocals, Bass, Lead guitar Ringo Starr : Drums John Lennon : Backing vocals, Lead vocals, Rhythm guitar George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Barrie Cameron : Saxophone David Glyde : Saxophone Alan Holmes : Saxophone John Lee : Trombone Unknown musician(s) : French horn, Tambourine, Trombone

Session Recording: Feb 08, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Feb 16, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Mar 13, 28 & 29, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Apr 19, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise)

1:19 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Bass, Bass guitar, Lead vocals, Organ, Vocals Ringo Starr : Drums, Lead vocals, Maracas, Tambourine, Vocals John Lennon : Lead vocals, Rhythm guitar, Vocals George Harrison : Lead guitar, Lead vocals, Vocals George Martin : Organ, Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Unknown musician(s) : Maracas

Session Recording: Apr 01, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio One, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Apr 01, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio One, Abbey Road

5:37 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Bass, Final piano chord, Lead vocals, Piano Ringo Starr : Congas, Drums, Final piano chord John Lennon : Acoustic guitar, Final piano chord, Lead vocals, Tambourine George Harrison : Maracas George Martin : Harmonium, Orchestral arrangement, Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Jack Brymer : Clarinet Mal Evans : Alarm clock, Final piano chord Sidney Sax : Violin Francesc Gabarró Solé : Cello Jürgen Hess : Violin John Underwood : Viola Alan Civil : French horn David Mason : Trumpet Neill Sanders : French horn Erich Gruenberg : Violin Granville Delmé Jones : Violin Bill Monro : Violin Hans Geiger : Violin D Bradley : Violin Lionel Bentley : Violin David McCallum Sr. : Violin Donald Weekes : Violin Henry Datyner : Violin Ernest Scott : Violin Gwynne Edwards : Viola Bernard Davis : Viola John Meek : Viola Dennis Vigay : Cello Alan Dalziel : Cello Alex Nifosi : Cello Cyril MacArthur : Double bass Gordon Pearce : Double bass John Marston : Harp Basil Tschaikov : Clarinet Roger Lord : Oboe N Fawcett : Bassoon Alfred Waters : Bassoon Clifford Seville : Flute David Sanderman : Flute Monty Montgomery : Trumpet Harold Jackson : Trumpet Raymond Brown : Trombone Raymond Premru : Trombone T Moore : Trombone Michael Barnes : Tubas Tristan Fry : Percussion, Timpani Marijke Koger : Tambourine

Session Recording: Jan 19, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jan 20, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Feb 03, 10 and 22, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Feb 22, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Run-out groove of the LP

Written by Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, John Lennon, George Harrison

0:02 • Studio version

Paul McCartney : Noises, Vocals Ringo Starr : Noises, Vocals John Lennon : Noises, Vocals George Harrison : Noises, Vocals George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Engineer

Session Recording: Apr 21, 1967 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

From Wikipedia:

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is the eighth studio album by the English rock band the Beatles. Released on 26 May 1967, Sgt. Pepper is regarded by musicologists as an early concept album that advanced the roles of sound composition, extended form, psychedelic imagery, record sleeves, and the producer in popular music. The album had an immediate cross-generational impact and was associated with numerous touchstones of the era’s youth culture, such as fashion, drugs, mysticism, and a sense of optimism and empowerment. Critics lauded the album for its innovations in songwriting, production and graphic design, for bridging a cultural divide between popular music and high art, and for reflecting the interests of contemporary youth and the counterculture.

At the end of August 1966, the Beatles had permanently retired from touring and pursued individual interests for the next three months. During a return flight to London in November, Paul McCartney had an idea for a song involving an Edwardian military band that formed the impetus of the Sgt. Pepper concept. For this project, they continued the technological experimentation marked by their previous album, Revolver, this time without an absolute deadline for completion. Sessions began on 24 November at EMI Studios with compositions inspired by the Beatles’ youth, but after pressure from EMI, the songs “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane” were released as a double A-side single in February 1967 and left off the LP. The album was then loosely conceptualised as a performance by the fictional Sgt. Pepper band, an idea that was conceived after recording the title track.

A key work of British psychedelia, Sgt. Pepper is considered one of the first art rock LPs and a progenitor to progressive rock. It incorporates a range of stylistic influences, including vaudeville, circus, music hall, avant-garde, and Western and Indian classical music. With assistance from producer George Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick, much of the recordings were coloured with sound effects and tape manipulation, as exemplified on “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds“, “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!” and “A Day in the Life“. Recording was completed on 21 April. The cover, which depicts the Beatles posing in front of a tableau of celebrities and historical figures, was designed by the pop artists Peter Blake and Jann Haworth.

Sgt. Pepper‘s release was a defining moment in pop culture, heralding the album era and the 1967 Summer of Love, while its reception achieved full cultural legitimisation for popular music and recognition for the medium as a genuine art form. The first Beatles album to be released with the same track listing in both the UK and the US, it spent 27 weeks at number one on the Record Retailer chart in the United Kingdom and 15 weeks at number one on the Billboard Top LPs chart in the United States. In 1968, it won four Grammy Awards, including Album of the Year, the first rock LP to receive this honour; in 2003, it was inducted into the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”. It has topped several critics’ and listeners’ polls for the best album of all time, including those published by Rolling Stone magazine and in the book All Time Top 1000 Albums, and the UK’s “Music of the Millennium” poll. More than 32 million copies had been sold worldwide as of 2011. It remains one of the best-selling albums of all time and was still, in 2018, the UK’s best-selling studio album. A remixed and expanded edition of the album was released in 2017.

Background

By late 1965, the Beatles had grown weary of live performance. In John Lennon’s opinion, they could “send out four waxworks … and that would satisfy the crowds. Beatles concerts are nothing to do with music anymore. They’re just bloody tribal rites.” In June 1966, two days after finishing the album Revolver, the group set off for a tour that started in West Germany. While in Hamburg they received an anonymous telegram stating: “Do not go to Tokyo. Your life is in danger.” The threat was taken seriously in light of the controversy surrounding the tour among Japan’s religious and conservative groups, with particular opposition to the Beatles’ planned performances at the sacred Nippon Budokan arena. As an added precaution, 35,000 police were mobilised and tasked with protecting the group, who were transported from hotels to concert venues in armoured vehicles. The Beatles then performed in the Philippines, where they were threatened and manhandled by its citizens for not visiting First Lady Imelda Marcos. The group were angry with their manager, Brian Epstein, for insisting on what they regarded as an exhausting and demoralising itinerary.

The publication in the US of Lennon’s remarks about the Beatles being “more popular than Jesus” then embroiled the band in controversy and protest in America’s Bible Belt. A public apology eased tensions, but a US tour in August that was marked by reduced ticket sales, relative to the group’s record attendances in 1965, and subpar performances proved to be their last. The author Nicholas Schaffner writes:

To the Beatles, playing such concerts had become a charade so remote from the new directions they were pursuing that not a single tune was attempted from the just-released Revolver LP, whose arrangements were for the most part impossible to reproduce with the limitations imposed by their two-guitars-bass-and-drums stage lineup.

On the Beatles’ return to England, rumours began to circulate that they had decided to break up. George Harrison informed Epstein that he was leaving the band, but he was persuaded to stay on the assurance that there would be no more tours. The group took a three-month break, during which they focused on individual interests. Harrison travelled to India for six weeks to study the sitar under the instruction of Ravi Shankar and develop his interest in Hindu philosophy. Having been the last of the Beatles to concede that their live performances had become futile, Paul McCartney collaborated with Beatles producer George Martin on the soundtrack for the film The Family Way and holidayed in Kenya with Mal Evans, one of the Beatles’ tour managers. Lennon acted in the film How I Won the War and attended art showings, such as one at the Indica Gallery where he met his future wife Yoko Ono. Ringo Starr used the break to spend time with his wife Maureen and son Zak.

Inspiration and conception

While in London without his bandmates, McCartney took the hallucinogenic drug LSD (or “acid”) for the first time, having long resisted Lennon and Harrison’s insistence that he join them and Starr in experiencing its perception-heightening effects. According to author Jonathan Gould, this initiation into LSD afforded McCartney the “expansive new sense of possibility” that defined the group’s next project, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Gould adds that McCartney’s succumbing to peer pressure allowed Lennon “to play the role of psychedelic guide” to his songwriting partner, thereby facilitating a closer collaboration between the two than had been evident since early in the Beatles’ career. For his part, Lennon had turned deeply introspective during the filming of How I Won the War in southern Spain in September 1966. His anxiety over his and the Beatles’ future was reflected in “Strawberry Fields Forever“, a song that provided the initial theme, regarding a Liverpool childhood, of the new album. On his return to London, Lennon embraced the city’s arts culture, of which McCartney was a part, and shared his bandmate’s interest in avant-garde and electronic-music composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen, John Cage and Luciano Berio.

In November, during his and Evans’ return flight from Kenya, McCartney had an idea for a song that eventually formed the impetus of the Sgt. Pepper concept. His idea involved an Edwardian-era military band, for which Evans invented a name in the style of contemporary San Francisco-based groups such as Big Brother and the Holding Company and Quicksilver Messenger Service. In February 1967, McCartney suggested that the new album should represent a performance by the fictional band. This alter ego group would give them the freedom to experiment musically by releasing them from their image as Beatles. Martin recalled that the concept was not discussed at the start of the sessions, but it subsequently gave the album “a life of its own”.

Portions of Sgt. Pepper reflect the Beatles’ general immersion in the blues, Motown and other American popular musical traditions. The author Ian MacDonald writes that when reviewing their rivals’ recent work in late 1966, the Beatles identified the most significant LP as the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, which Brian Wilson, the band’s leader, had created in response to the Beatles’ Rubber Soul. McCartney was highly impressed with the “harmonic structures” and choice of instruments used on Pet Sounds, and said that these elements encouraged him to think the Beatles could “get further out” than the Beach Boys had. He identified Pet Sounds as his main musical inspiration for Sgt. Pepper, adding that “[we] nicked a few ideas”, although he felt it lacked the avant-garde quality he was seeking. Freak Out! by the Mothers of Invention has also been cited as having influenced Sgt. Pepper. According to the biographer Philip Norman, during the recording sessions McCartney repeatedly stated: “This is our Freak Out!” The music journalist Chet Flippo stated that McCartney was inspired to record a concept album after hearing Freak Out!

Indian music was another touchstone on Sgt. Pepper, principally for Lennon and Harrison. In a 1967 interview, Harrison said that the Beatles’ ongoing success had encouraged them to continue developing musically and that, given their standing, “We can do things that please us without conforming to the standard pop idea. We are not only involved in pop music, but all music.” McCartney envisioned the Beatles’ alter egos being able to “do a bit of B.B. King, a bit of Stockhausen, a bit of Albert Ayler, a bit of Ravi Shankar, a bit of Pet Sounds, a bit of the Doors”. He saw the group as “pushing frontiers” similar to other composers of the time, even though the Beatles did not “necessarily like what, say, Berio was doing”.

Recording and production – Recording history

Sessions began on 24 November 1966 in Studio Two at EMI Studios (subsequently Abbey Road Studios), marking the first time that the Beatles had come together since September. Afforded the luxury of a nearly limitless recording budget, and with no absolute deadline for completion, the band booked open-ended sessions that started at 7 pm and allowed them to work as late as they wanted. They began with “Strawberry Fields Forever”, followed by two other songs that were thematically linked to their childhoods: “When I’m Sixty-Four“, the first session for which took place on 6 December, and “Penny Lane“.

“Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane” were subsequently released as a double A-side in February 1967 after EMI and Epstein pressured Martin for a single. When it failed to reach number one in the UK, British press agencies speculated that the group’s run of success might have ended, with headlines such as “Beatles Fail to Reach the Top”, “First Time in Four Years” and “Has the Bubble Burst?” In keeping with the band’s approach to their previously issued singles, the songs were then excluded from Sgt. Pepper. Martin later described the decision to drop these two songs as “the biggest mistake of my professional life”. In his judgment, “Strawberry Fields Forever”, which he and the band spent an unprecedented 55 hours of studio time recording, “set the agenda for the whole album”. He explained: “It was going to be a record … [with songs that] couldn’t be performed live: they were designed to be studio productions and that was the difference.” McCartney declared: “Now our performance is that record.”

According to the musicologist Walter Everett, Sgt. Pepper marks the beginning of McCartney’s ascendancy as the Beatles’ dominant creative force. He wrote more than half of the album’s material while asserting increasing control over the recording of his compositions. In an effort to get the right sound, the Beatles attempted numerous re-takes of McCartney’s song “Getting Better“. When the decision was made to re-record the basic track, Starr was summoned to the studio, but called off soon afterwards as the focus switched from rhythm to vocal tracking. Much of the bass guitar on the album was mixed upfront. Preferring to overdub his bass part last, McCartney tended to play other instruments when recording a song’s backing track. This approach afforded him the time to devise bass lines that were melodically adventurous – one of the qualities he especially admired in Wilson’s work on Pet Sounds – and complemented the song’s final arrangement. McCartney played keyboard instruments such as piano, grand piano and Lowrey organ, in addition to electric guitar on some songs, while Martin variously contributed on Hohner Pianet, harpsichord and harmonium. Lennon’s songs similarly showed a preference for keyboard instruments.

Although Harrison’s role as lead guitarist was limited during the sessions, Everett considers that “his contribution to the album is strong in several ways.” He provided Indian instrumentation in the form of sitar, tambura and swarmandal, and Martin credited him with being the most committed of the Beatles in striving for new sounds. Starr’s adoption of loose calfskin heads for his tom-toms ensured his drum kit had a deeper timbre than he had previously achieved with plastic heads. As on Revolver, the Beatles increasingly used session musicians, particularly for classical-inspired arrangements. Norman comments that Lennon’s prominent vocal on some of McCartney’s songs “hugely enhanced their atmosphere”, particularly “Lovely Rita“.

Within an hour of completing the last overdubs on the album’s songs, on 20 April 1967, the group returned to Harrison’s “Only a Northern Song“, the basic track of which they had taped in February. The Beatles overdubbed random sounds and instrumentation before submitting it as the first of four new songs they were contracted to supply to United Artists for inclusion in the animated film Yellow Submarine. In author Mark Lewisohn’s description, it was a “curious” session, but one that demonstrated the Beatles’ “tremendous appetite for recording”. During the Sgt. Pepper sessions, the band also recorded “Carnival of Light“, a McCartney-led experimental piece created for the Million Volt Light and Sound Rave, held at the Roundhouse Theatre on 28 January and 4 February. The album was completed on 21 April with the recording of random noises and voices that were included on the run-out groove, preceded by a high-pitched tone that could be heard by dogs but was inaudible to most human ears.

Recording and production – Studio ambience and happenings

The Beatles sought to inject an atmosphere of celebration into the recording sessions. Weary of the bland look inside EMI, they introduced psychedelic lighting to the studio space, including a device on which five red fluorescent tubes were fixed to a microphone stand, a lava lamp, a red darkroom lamp, and a stroboscope, the last of which they soon abandoned. Harrison later said the studio became the band’s clubhouse for Sgt. Pepper; David Crosby, Mick Jagger and Donovan were among the musician friends who visited them there. The band members also dressed up in psychedelic fashions, leading one session trumpeter to wonder whether they were in costume for a new film. Drug-taking was prevalent during the sessions, with Martin later recalling that the group would steal away to “have something”.

The 10 February session for orchestral overdubs on “A Day in the Life” was staged as a happening typical of the London avant-garde scene. The Beatles invited numerous friends and the session players wore formal dinner-wear augmented with fancy-dress props. Overseen by NEMS employee Tony Bramwell, the proceedings were filmed on seven handheld cameras, with the band doing some of the filming. Following this event, the group considered making a television special based on the album. Each of the songs was to be represented with a clip directed by a different director, but the cost of recording Sgt. Pepper made the idea prohibitive to EMI. For the 15 March session for “Within You Without You“, Studio Two was transformed with Indian carpets placed on the walls, dimmed lighting and burning incense to evoke the requisite Indian mood. Lennon described the session as a “great swinging evening” with “400 Indian fellas” among the guests.

The Beatles took an acetate disc of the completed album to the flat of American singer Cass Elliot, off King’s Road in Chelsea. There, at six in the morning, they played it at full volume with speakers set in open window frames. The group’s friend and former press agent, Derek Taylor, remembered that residents of the neighbourhood opened their windows and listened without complaint to what they understood to be unreleased Beatles music.

Recording and production – Technical aspects

In his book on ambient music, The Ambient Century: From Mahler to Moby, Mark Prendergast views Sgt. Pepper as the Beatles’ “homage” to Stockhausen and Cage, adding that its “rich, tape-manipulated sound” shows the influence of electronic and experimental composer Pierre Schaeffer. Martin recalled that Sgt. Pepper “grew naturally out of Revolver“, marking “an era of almost continuous technological experimentation”. The album was recorded using four-track equipment, since eight-track tape recorders were not operational in commercial studios in London until late 1967. As with previous Beatles albums, the Sgt. Pepper recordings made extensive use of reduction mixing, a technique in which one to four tracks from one recorder are mixed and dubbed down onto a master four-track machine, enabling the engineers to give the group a virtual multitrack studio. EMI’s Studer J37 four-track machines were well suited to reduction mixing, as the high quality of the recordings that they produced minimised the increased noise associated with the process. When recording the orchestra for “A Day in the Life”, Martin synchronised a four-track recorder playing the Beatles’ backing track to another one taping the orchestral overdub. The engineer Ken Townsend devised a method for accomplishing this by using a 50 Hz control signal between the two machines.

The production on “Strawberry Fields Forever” was especially complex, involving the innovative splicing of two takes that were recorded in different tempos and pitches. Emerick remembers that during the recording of Revolver, “we had got used to being asked to do the impossible, and we knew that the word ‘no’ didn’t exist in the Beatles’ vocabulary.” A key feature of Sgt. Pepper is Martin and Emerick’s liberal use of signal processing to shape the sound of the recording, which included the application of dynamic range compression, reverb and signal limiting. Relatively new modular effects units were used, such as running voices and instruments through a Leslie speaker. Several innovative production techniques feature prominently on the recordings, including direct injection, pitch control and ambiophonics. The bass part on “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” was the first example of the Beatles recording via direct injection (DI), which Townsend devised as a method for plugging electric guitars directly into the recording console. In Kenneth Womack’s opinion, the use of DI on the album’s title track “afforded McCartney’s bass with richer textures and tonal clarity”.

Some of the mixing employed automatic double tracking (ADT), a system that uses tape recorders to create a simultaneous doubling of a sound. ADT was invented by Townsend during the Revolver sessions in 1966 especially for the Beatles, who regularly expressed a desire for a technical alternative to having to record doubled lead vocals. Another important effect was varispeeding, a technique that the Beatles used extensively on Revolver. Martin cites “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” as having the most variations of tape speed on Sgt. Pepper. During the recording of Lennon’s vocals, the tape speed was reduced from 50 cycles per second to 45, which produced a higher and thinner-sounding track when played back at the normal speed. For the album’s title track, the recording of Starr’s drum kit was enhanced by the use of damping and close-miking. MacDonald credits the new recording technique with creating a “three-dimensional” sound that, along with other Beatles innovations, engineers in the US would soon adopt as standard practice.

Artistic experimentation, such as the placement of random gibberish in the run-out groove, became one of the album’s defining features. Sgt. Pepper was the first pop album to be mastered without the momentary gaps that are typically placed between tracks as a point of demarcation. It made use of two crossfades that blended songs together, giving the impression of a continuous live performance. Although both stereo and monaural mixes of the album were prepared, the Beatles were minimally involved in what they regarded as the less important stereo mix sessions, leaving the task to Martin and Emerick. Emerick recalls: “We spent three weeks on the mono mixes and maybe three days on the stereo.” Most listeners ultimately heard only the stereo version. He estimates that the group spent 700 hours on the LP, more than 30 times that of the first Beatles album, Please Please Me, which cost £400 to produce. The final cost of Sgt. Pepper was approximately £25,000 (equivalent to £483,000 in 2021).

Recording and production – Band dynamics

Author Robert Rodriguez writes that while Lennon, Harrison and Starr embraced the creative freedom afforded by McCartney’s band-within-a-band idea, they “went along with the concept with varying degrees of enthusiasm”. Studio personnel recalled that Lennon had “never seemed so happy” as during the Sgt. Pepper sessions. In a 1969 interview with Barry Miles, however, Lennon said he was depressed and that while McCartney was “full of confidence”, he was “going through murder”. Lennon explained his view of the album’s concept: “Paul said, ‘Come and see the show’, I didn’t. I said, ‘I read the news today, oh boy.'”

Everett describes Starr as having been “largely bored” during the sessions, with the drummer later lamenting: “The biggest memory I have of Sgt. Pepper … is I learned to play chess”. In The Beatles Anthology, Harrison said he had little interest in McCartney’s concept of a fictitious group and that, after his experiences in India, “my heart was still out there … I was losing interest in being ‘fab’ at that point.” Harrison added that, having enjoyed recording Rubber Soul and Revolver, he disliked how the group’s approach on Sgt. Pepper became “an assembly process” whereby, “A lot of the time it ended up with just Paul playing the piano and Ringo keeping the tempo, and we weren’t allowed to play as a band as much.”

In Lewisohn’s opinion, Sgt. Pepper represents the group’s last unified effort, displaying a cohesion that deteriorated immediately following the album’s completion and entirely disappeared by the release of The Beatles (also known as the “White Album”) in 1968. Martin recalled in 1987 that throughout the making of Sgt. Pepper, “There was a very good spirit at that time between all the Beatles and ourselves. We were all conscious that we were doing something that was great.” He said that while McCartney effectively led the project, and sometimes annoyed his bandmates, “Paul appreciated John’s contribution on Pepper. In terms of quantity, it wasn’t great, but in terms of quality, it was enormous.”

Songs – Overview

Among musicologists, Allan Moore says that Sgt. Pepper is composed mainly of rock and pop music, while Michael Hannan and Naphtali Wagner both see it as an album of various genres; Hannan says it features “a broad variety of musical and theatrical genres”. According to Hannan and Wagner, the music incorporates the stylistic influences of rock and roll, vaudeville, big band, piano jazz, blues, chamber, circus, music hall, avant-garde, and Western and Indian classical music. Wagner feels the album’s music reconciles the “diametrically opposed aesthetic ideals” of classical and psychedelia, achieving a “psycheclassical synthesis” of the two forms. Musicologist John Covach describes Sgt. Pepper as “proto-progressive”.

According to author George Case, all of the songs on Sgt. Pepper were perceived by contemporary listeners as being drug-inspired, with 1967 marking the pinnacle of LSD’s influence on pop music. Shortly before the album’s release, the BBC banned “A Day in the Life” from British radio because of the phrase “I’d love to turn you on”; the BBC stated that it could “encourage a permissive attitude towards drug-taking”. Although Lennon and McCartney denied any drug-related interpretation of the song at the time, McCartney later suggested that the line referred to either drugs or sex. The meaning of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” became the subject of speculation, as many believed that the title was code for LSD. In “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!“, the reference to “Henry the Horse” contains two common slang terms for heroin. Fans speculated that Henry the Horse was a drug dealer and “Fixing a Hole” was a reference to heroin use. Others noted lyrics such as “I get high” from “With a Little Help from My Friends“, “take some tea” – slang for cannabis use – from “Lovely Rita”, and “digging the weeds” from “When I’m Sixty-Four”.

The author Sheila Whiteley attributes Sgt. Pepper‘s underlying philosophy not only to the drug culture, but also to metaphysics and the non-violent approach of the flower power movement. The musicologist Oliver Julien views the album as an embodiment of “the social, the musical, and more generally, the cultural changes of the 1960s”. The album’s primary value, according to Moore, is its ability to “capture, more vividly than almost anything contemporaneous, its own time and place”. Whiteley agrees, crediting the album with “provid[ing] a historical snapshot of England during the run-up to the Summer of Love”. Several scholars have applied a hermeneutic strategy to their analysis of Sgt. Pepper‘s lyrics, identifying loss of innocence and the dangers of overindulgence in fantasies or illusions as the most prominent themes.

Songs – Side one

“Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”

Sgt. Pepper opens with the title track, starting with 10 seconds of the combined sounds of a pit orchestra warming up and an audience waiting for a concert, creating the illusion of the album as a live performance. McCartney serves as the master of ceremonies, welcoming the audience to a twentieth-anniversary reunion concert by Sgt. Pepper’s band, who, led by Lennon, then sing a message of appreciation for the crowd’s warm response. Womack says the lyric bridges the fourth wall between the artist and their audience. He argues that, paradoxically, the lyrics “exemplify the mindless rhetoric of rock concert banter” while “mock[ing] the very notion of a pop album’s capacity for engendering authentic interconnection between artist and audience”. In his view, the mixed message ironically serves to distance the group from their fans while simultaneously “gesturing toward” them as alter egos.

The song’s five-bar bridge is filled by a French horn quartet. Womack credits the recording’s use of a brass ensemble with distorted electric guitars as an early example of rock fusion. MacDonald agrees, describing the track as an overture rather than a song, and a “fusion of Edwardian variety orchestra” and contemporary hard rock. Hannan describes the track’s unorthodox stereo mix as “typical of the album”, with the lead vocal in the right speaker during the verses, but in the left during the chorus and middle eight. McCartney returns as the master of ceremonies near the end of the song, announcing the entrance of an alter ego named Billy Shears.

“With a Little Help from My Friends”

The title track segues into “With a Little Help from My Friends” amid the sound of screaming fans recorded during a Beatles concert at the Hollywood Bowl. In his role as Billy Shears, Starr contributes a baritone lead vocal that Womack credits with imparting an element of “earnestness in sharp contrast with the ironic distance of the title track”. Written by Lennon and McCartney, the song’s lyrics centre on a theme of questions, beginning with Starr asking the audience whether they would leave if he sang out of tune. In the call-and-response style, Lennon, McCartney and Harrison go on to ask their bandmate questions about the meaning of friendship and true love; by the final verse, Starr provides unequivocal answers. In MacDonald’s opinion, the lyric is “at once communal and personal … [and] meant as a gesture of inclusivity; everyone could join in.” Everett comments that the track’s use of a major key double-plagal cadence became commonplace in pop music following the release of Sgt. Pepper.

“Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”

Despite widespread suspicion that the title of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” contained a hidden reference to LSD, Lennon insisted that it was derived from a pastel drawing by his four-year-old son Julian. A hallucinatory chapter from Lewis Carroll’s 1871 novel Through the Looking-Glass, a favourite of Lennon’s, inspired the song’s atmosphere. According to MacDonald, “the lyric explicitly recreates the psychedelic experience”.

The first verse begins with what Womack characterises as “an invitation in the form of an imperative” through the line: “Picture yourself in a boat on a river”, and continues with imaginative imagery, including “tangerine trees”, “rocking horse people” and “newspaper taxis”. The musical backing includes a phrase played by McCartney on a Lowrey organ, treated with ADT to sound like a celeste, and tambura drone. Harrison also contributed a lead guitar part that doubles Lennon’s vocal over the verses in the style of a sarangi player accompanying an Indian khyal singer. The music critic Tim Riley identifies the track as a moment “in the album, [where] the material world is completely clouded in the mythical by both text and musical atmosphere”.

“Getting Better”

MacDonald considers “Getting Better” to contain “the most ebullient performance” on Sgt. Pepper. Womack credits the track’s “driving rock sound” with distinguishing it from the album’s overtly psychedelic material; its lyrics inspire the listener “to usurp the past by living well and flourishing in the present”. He cites it as a strong example of Lennon and McCartney’s collaborative songwriting, particularly Lennon’s addition of the line “It can’t get no worse”, which serves as a “sarcastic rejoinder” to McCartney’s chorus: “It’s getting better all the time”. Lennon’s contribution to the lyric also includes a confessional regarding his having been violent with female companions: “I used to be cruel to my woman”. In Womack’s opinion, the song encourages the listener to follow the speaker’s example and “alter their own angst-ridden ways”: “Man I was mean, but I’m changing my scene and I’m doing the best that I can.”

“Fixing a Hole”

“Fixing a Hole” deals with McCartney’s desire to let his mind wander freely and to express his creativity without the burden of self-conscious insecurities. Womack interprets the lyric as “the speaker’s search for identity among the crowd”, in particular the “quests for consciousness and connection” that differentiate individuals from society as a whole. MacDonald characterises it as a “distracted and introverted track”, during which McCartney forgoes his “usual smooth design” in favour of “something more preoccupied”. He cites Harrison’s electric guitar solo as serving the track well, capturing its mood by conveying detachment. Womack notes McCartney’s adaptation of the lyric “a hole in the roof where the rain leaks in” from Elvis Presley’s “We’re Gonna Move“.

“She’s Leaving Home”

In Everett’s view, the lyrics to “She’s Leaving Home” address the problem of alienation “between disagreeing peoples”, particularly those distanced from each other by the generation gap. McCartney’s narrative details the plight of a young woman escaping the control of her parents, and was inspired by a piece about teenage runaways published in the Daily Mail. Lennon supplies a supporting vocal that conveys the parents’ anguish and confusion. It is the first track on Sgt. Pepper that eschews the use of guitars and drums, featuring only a string nonet with a harp. Music historian Doyle Greene views it as the first of the album’s songs to address “the crisis of middle-class life in the late 1960s” and comments on its surprisingly conservative sentiments, given McCartney’s absorption in the London avant-garde scene.

“Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!”

Lennon adapted the lyrics for “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!” from an 1843 poster for Pablo Fanque’s circus that he purchased at an antique shop in Kent on the day of filming the promotional film for “Strawberry Fields Forever”. Womack views the track as an effective blending of a print source and music, while MacDonald describes it as “a spontaneous expression of its author’s playful hedonism”. Tasked by Lennon to evoke a circus atmosphere so vivid that he could “smell the sawdust”, Martin and Emerick created a sound collage comprising randomly assembled recordings of harmoniums, harmonicas and calliopes. Everett says that the track’s use of Edwardian imagery thematically links it with the album’s title song. Gould also views “Mr. Kite!” as a return to the LP’s opening motif, albeit that of show business and with the focus now on performers and a show in a radically different setting.

Songs – Side two

“Within You Without You”

Harrison’s Hindustani classical music-inspired “Within You Without You” reflects his immersion in the teachings of the Hindu Vedas, while its musical form and Indian instrumentation, such as sitar, tabla, dilrubas and tamburas, recalls the Hindu devotional tradition known as bhajan. Harrison recorded the song with London-based Indian musicians from the Asian Music Circle; none of the other Beatles played on the recording. He and Martin then worked on a Western string arrangement that imitated the slides and bends typical of Indian music. The song’s pitch is derived from the eastern Khamaj scale, which is akin to the Mixolydian mode in the West.

MacDonald regards “Within You Without You” as “the most distant departure from the staple Beatles sound in their discography”, and a work that represents the “conscience” of the LP through the lyrics’ rejection of Western materialism. Womack calls it “quite arguably, the album’s ethical soul” and views the line “With our love we could save the world” as a concise reflection of the Beatles’ idealism that soon inspired the Summer of Love. The track ends with a burst of laughter gleaned from a tape in the EMI archive; some listeners interpreted this as a mockery of the song, but Harrison explained: “It’s a release after five minutes of sad music … You were supposed to hear the audience anyway, as they listen to Sergeant Pepper’s Show. That was the style of the album.”

“When I’m Sixty-Four”

MacDonald characterises McCartney’s “When I’m Sixty-Four” as a song “aimed chiefly at parents”, borrowing heavily from the English music hall style of George Formby, while invoking images of the illustrator Donald McGill’s seaside postcards. Its sparse arrangement includes clarinets, chimes and piano. Moore views the song as a synthesis of ragtime and pop, adding that its position following “Within You Without You” – a blend of Indian classical music and pop – demonstrates the diversity of the album’s material. He says the music hall atmosphere is reinforced by McCartney’s vocal delivery and the recording’s use of chromaticism, a harmonic pattern that can be traced to Scott Joplin’s “The Ragtime Dance” and “The Blue Danube” by Johann Strauss. Varispeeding was used on the track, raising its pitch by a semitone in an attempt to make McCartney sound younger. Everett comments that the lyric’s protagonist is sometimes associated with the Lonely Hearts Club Band, but in his opinion the song is thematically unconnected to the others on the album.

“Lovely Rita”

Womack describes “Lovely Rita” as a work of “full-tilt psychedelia” that contrasts sharply with the preceding track. Citing McCartney’s recollection that he drew inspiration from learning that the American term for a female traffic warden was a meter maid, Gould deems it a celebration of an encounter that evokes Swinging London and the contemporaneous chic for military-style uniforms. MacDonald regards the song as a “satire on authority” that is “imbued with an exuberant interest in life that lifts the spirits, dispersing self-absorption”. The arrangement includes a quartet of comb-and-paper kazoos, a piano solo by Martin, and a coda in which the Beatles indulge in panting, groaning and other vocalised sounds. In Gould’s view, the track represents “the show-stopper in the Pepper Band’s repertoire: a funny, sexy, extroverted song that comes closer to the spirit of rock ‘n’ roll than anything else on the album”.

“Good Morning Good Morning”

Lennon was inspired to write “Good Morning Good Morning” after watching a television commercial for Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, the jingle from which he adapted for the song’s refrain. The track uses the bluesy Mixolydian mode in A, which Everett credits with “perfectly express[ing] Lennon’s grievance against complacency”. According to Greene, the song contrasts sharply with “She’s Leaving Home” by providing “the more ‘avant-garde’ subversive study of suburban life”. The time signature varies across 5/4, 3/4 and 4/4, while the arrangement includes a horn section comprising members of Sounds Inc. MacDonald highlights the “rollicking” brass score, Starr’s drumming and McCartney’s “coruscating pseudo-Indian guitar solo” among the elements that convey a sense of aggression on a track he deems a “disgusted canter through the muck, mayhem, and mundanity of the human farmyard”. A series of animal noises appear during the fade-out that are sequenced – at Lennon’s request – so that each successive animal could conceivably scare or devour the preceding one. The sound of a chicken clucking overlaps with a stray guitar note at the start of the next track, creating a seamless transition between the two songs.

“Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise)”

“Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise)” follows as a segue to the album’s finale. The hard-rocking song was written after Neil Aspinall, the Beatles’ road manager, suggested that since “Sgt. Pepper” opened the album, the fictional band should make an appearance near the end. Sung by all four Beatles, the reprise omits the brass section from the title track and has a faster tempo. With Harrison on lead guitar, it serves as a rare example from the Sgt. Pepper sessions where the group taped a basic track live with their usual stage instrumentation. MacDonald finds the Beatles’ excitement tangibly translated on the recording, which is again augmented with ambient crowd noise.

“A Day in the Life”

The last chord of the “Sgt. Pepper” reprise segues amid audience applause to acoustic guitar strumming and the start of what Moore calls “one of the most harrowing songs ever written”. “A Day in the Life” consists of four verses by Lennon, a bridge, two aleatoric orchestral crescendos, and an interpolated middle part written and sung by McCartney. The first crescendo serves as a segue between the third verse and the middle part, leading to a bridge known as the “dream sequence”. Lennon drew inspiration for the lyrics from a Daily Mail report on potholes in the Lancashire town of Blackburn and an article in the same newspaper relating to the death of Beatles friend and Guinness heir Tara Browne.

According to Martin, Lennon and McCartney were equally responsible for the decision to use an orchestra. Martin said that Lennon requested “a tremendous build-up, from nothing up to something absolutely like the end of the world”, while McCartney realised this idea by drawing inspiration from Cage and Stockhausen. Womack describes Starr’s performance as “one of his most inventive drum parts on record”. The thunderous piano chord that concludes the track and the album was produced by recording Lennon, Starr, McCartney and Evans simultaneously sounding an E major chord on three separate pianos; Martin then augmented the sound with a harmonium.

Riley characterises the song as a “postlude to the Pepper fantasy … that sets all the other songs in perspective”, while shattering the illusion of “Pepperland” by introducing the “parallel universe of everyday life”. MacDonald describes the track as “a song not of disillusionment with life itself, but of disenchantment with the limits of mundane perception”.

As “A Day in the Life” ends, a 15-kilohertz high-frequency tone is heard; it was added at Lennon’s suggestion with the intention that it would annoy dogs. This is followed by the sounds of backwards laughter and random gibberish that were pressed into the record’s concentric run-out groove, which loops back into itself endlessly on any record player not equipped with an automatic needle return. Lennon can be heard saying, “Been so high”, followed by McCartney’s response: “Never could be any other way.”

Concept

According to Womack, with Sgt. Pepper‘s opening song “the Beatles manufacture an artificial textual space in which to stage their art.” The reprise of the title song appears on side two, just before the climactic “A Day in the Life”, creating a framing device. In Lennon and Starr’s view, only the first two songs and the reprise are conceptually connected. In a 1980 interview, Lennon stated that his compositions had nothing to do with the Sgt. Pepper concept, adding: “Sgt. Pepper is called the first concept album, but it doesn’t go anywhere … it works because we said it worked.”

In MacFarlane’s view, the Beatles “chose to employ an overarching thematic concept in an apparent effort to unify individual tracks”. Everett contends that the album’s “musical unity results … from motivic relationships between key areas, particularly involving C, E, and G”. Moore argues that the recording’s “use of common harmonic patterns and falling melodies” contributes to its overall cohesiveness, which he describes as narrative unity, but not necessarily conceptual unity. MacFarlane agrees, suggesting that with the exception of the reprise, the album lacks the melodic and harmonic continuity that is consistent with cyclic form.

In a 1995 interview, McCartney recalled that the Liverpool childhood theme behind the first three songs recorded during the Sgt. Pepper sessions was never formalised as an album-wide concept, but he said that it served as a “device” or underlying theme throughout the project. MacDonald identifies allusions to the Beatles’ upbringing throughout Sgt. Pepper that are “too persuasive to ignore”. These include evocations of the postwar Northern music-hall tradition, references to Northern industrial towns and Liverpool schooldays, Lewis Carroll-inspired imagery (acknowledging Lennon’s favourite childhood reading), the use of brass instrumentation in the style of park bandstand performances (familiar to McCartney through his visits to Sefton Park), and the album cover’s flower arrangement akin to a floral clock. Norman partly agrees; he says that “In many ways, the album carried on the childhood and Liverpool theme with its circus and fairground effects, its pervading atmosphere of the traditional northern music hall that was in both its main creators’ [McCartney and Lennon’s] blood.”

Packaging – Front cover

Pop artists Peter Blake and Jann Haworth designed the album cover for Sgt. Pepper. Blake recalled of the concept: “I offered the idea that if they had just played a concert in the park, the cover could be a photograph of the group just after the concert with the crowd who had just watched the concert, watching them.” He added, “If we did this by using cardboard cut-outs, it could be a magical crowd of whomever they wanted.” According to McCartney, he himself provided the ink drawing on which Blake and Haworth based the design. The cover was art-directed by Robert Fraser and photographed by Michael Cooper.

The front of the LP includes a colourful collage featuring the Beatles in costume as Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, standing with a group of life-sized cardboard cut-outs of famous people. Each of the Beatles sports a heavy moustache, after Harrison had first grown one as a disguise during his visit to India. The moustaches reflected the growing influence of hippie style trends, while the group’s clothing, in Gould’s description, “spoofed the vogue in Britain for military fashions”. The centre of the cover depicts the Beatles standing behind a bass drum on which fairground artist Joe Ephgrave painted the words of the album’s title. In front of the drum is an arrangement of flowers that spell out “Beatles”. The group are dressed in satin day-glo-coloured military-style uniforms that were manufactured by the London theatrical costumer M. Berman Ltd. Next to the Beatles are wax sculptures of the band members in their suits and moptop haircuts from the Beatlemania era, borrowed from Madame Tussauds. Amid the greenery are figurines of the Eastern deities Buddha and Lakshmi.

The cover collage includes 57 photographs and nine waxworks. Author Ian Inglis views the tableau “as a guidebook to the cultural topography of the decade” that conveyed the increasing democratisation of society whereby “traditional barriers between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture were being eroded”, while Case cites it as the most explicit demonstration of pop culture’s “continuity with the avant-gardes of yesteryear”. The final grouping included composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, along with singers such as Bob Dylan and Bobby Breen; film stars Marlon Brando, Tyrone Power, Tony Curtis, Marlene Dietrich, Mae West and Marilyn Monroe; artist Aubrey Beardsley; boxer Sonny Liston and footballer Albert Stubbins. Also included were comedians Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy; writers H.G. Wells, Oscar Wilde, Lewis Carroll, and Dylan Thomas; and the philosophers and scientists Karl Marx, Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. Harrison chose the Self-Realization Fellowship gurus Mahavatar Babaji, Lahiri Mahasaya, Sri Yukteswar and Paramahansa Yogananda. The Rolling Stones are represented by a doll wearing a shirt emblazoned with a message of welcome to the band.

Fearing controversy, EMI rejected Lennon’s request for images of Adolf Hitler and Jesus Christ and Harrison’s for Mahatma Gandhi. When McCartney was asked why the Beatles did not include Elvis Presley among the musical artists, he replied: “Elvis was too important and too far above the rest even to mention.” Starr was the only Beatle who offered no suggestions for the collage, telling Blake, “Whatever the others say is fine by me.” The final cost for the cover art was nearly £3,000 (equivalent to £58,000 in 2021), an extravagant sum for a time when album covers would typically cost around £50 (equivalent to £1,000 in 2021).

Packaging – Back cover, gatefold and cut-outs

The 30 March 1967 photo session with Cooper also produced the back cover and the inside gatefold, which Inglis describes as conveying “an obvious and immediate warmth … which distances it from the sterility and artifice typical of such images”. McCartney recalled the inner-gatefold image as an example of the Beatles’ interest in “eye messages”, adding: “So with Michael Cooper’s inside photo, we all said, ‘Now look into this camera and really say I love you! Really try and feel love; really give love through this!’ … [And] if you look at it you’ll see the big effort from the eyes.” In Lennon’s description, Cooper’s photos of the band showed “two people who are flying [on drugs], and two who aren’t”.

The album’s lyrics were printed in full on the back cover, the first time this had been done on a rock LP. The record’s inner sleeve featured artwork by the Dutch design team the Fool that eschewed for the first time the standard white paper in favour of an abstract pattern of waves of maroon, red, pink and white. Included as a bonus gift was a sheet of cardboard cut-outs designed by Blake and Haworth. These consisted of a postcard-sized portrait of Sgt. Pepper (probably based on a photograph of British Army officer James Melville Babington, but also noted as being similar to a statue from Lennon’s house that was used on the front cover), a fake moustache, two sets of sergeant stripes, two lapel badges, and a stand-up cut-out of the band in their satin uniforms. Moore writes that the inclusion of these items helped fans “pretend to be in the band”.

Release – Radio previews and launch party

The album was previewed on the pirate radio station Radio London on 12 May and officially on the BBC Light Programme’s show Where It’s At, by Kenny Everett, on 20 May. Everett played the entire album apart from “A Day in the Life”. The day before Everett’s broadcast, Epstein hosted a launch party for music journalists and disc jockeys at his house in Belgravia in central London. The event was a new initiative in pop promotion and furthered the significance of the album’s release. Melody Maker‘s reporter described it as the first “listen-in” and typical of the Beatles’ penchant for innovation.

The party marked the band’s first group interaction with the press in close to a year. Norrie Drummond of the NME wrote that they had been “virtually incommunicado” over that time, leading a national newspaper to complain that the band were “contemplative, secretive and exclusive”. Some of the journalists present were shocked by the Beatles’ appearance, particularly that of Lennon and Harrison, as the band members’ bohemian attire contrasted sharply with their former image. Music journalist Ray Coleman recalled that Lennon looked “haggard, old, ill” and clearly under the influence of drugs. Biographer Howard Sounes likens the Beatles’ presence to a gathering of the British royal family and highlights a photo from the event (reproduced at right) that shows Lennon shaking McCartney’s hand “in an exaggeratedly congratulatory way, throwing his head back in sarcastic laughter”.

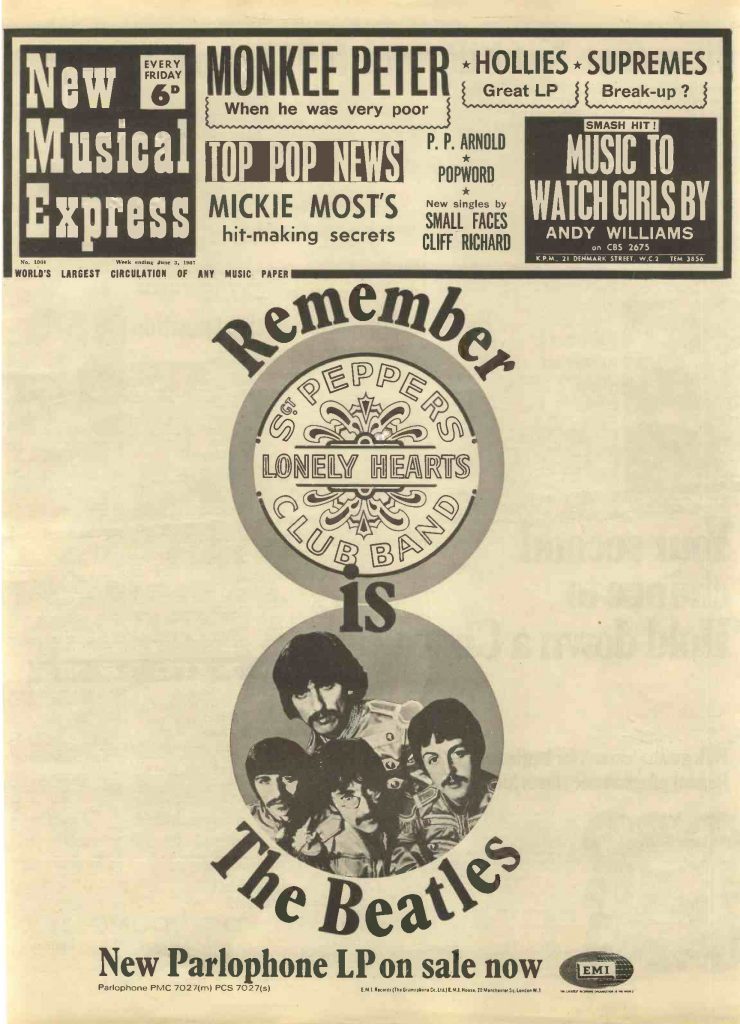

On 26 May, Sgt. Pepper was given a rush-release in the UK, ahead of the scheduled date of 1 June. The band’s eighth LP, it was the first Beatles album where the track listings were exactly the same for the UK and US versions. The US release took place on 2 June. Capitol Records’ advertising for the album emphasised that the Beatles and Sgt. Pepper’s band were one and the same.

Release – Public reaction

Sgt. Pepper was widely perceived by listeners as the soundtrack to the Summer of Love, during a year that author Peter Lavezzoli calls “a watershed moment in the West when the search for higher consciousness and an alternative world view had reached critical mass”. Rolling Stone magazine’s Langdon Winner recalled:

The closest Western Civilization has come to unity since the Congress of Vienna in 1815 was the week the Sgt. Pepper album was released. In every city in Europe and America the radio stations played [it] … and everyone listened … For a brief while the irreparable fragmented consciousness of the West was unified, at least in the minds of the young.

According to Riley, the album “drew people together through the common experience of pop on a larger scale than ever before”. In MacDonald’s description, an “almost religious awe surrounded the LP”; he says that its impact was cross-generational, as “Young and old alike were entranced”, and era-defining, in that the “psychic shiver” it inspired across the world was “nothing less than a cinematic dissolve from one Zeitgeist to another”. In his view, Sgt. Pepper conveyed the psychedelic experience so effectively to listeners unfamiliar with hallucinogenic drugs that “If such a thing as a cultural ‘contact high’ is possible, it happened here.” Music journalist Mark Ellen, a teenager in 1967, recalls listening to part of the album at a friend’s house and then hearing the rest playing at the next house he visited as if the record was emanating communally from “one giant Dansette”. He says the most remarkable thing was its acceptance by adults who had turned against the Beatles when they became “gaunt and enigmatic”, and how the group, recast as polished “masters of ceremony”, were now “the very family favourites they’d sought to satirise”.

Writing in his book Electric Shock, Peter Doggett describes Sgt. Pepper as “the biggest pop happening” to take place between the Beatles’ debut on American television in February 1964 and Lennon’s murder in December 1980, while Norman writes: “A whole generation, still used to happy landmarks through life, would always remember exactly when and where they first played it …” The album’s impact was felt at the Monterey International Pop Festival, the second event in the Summer of Love, organised by Taylor and held over 16–18 June in county fairgrounds south of San Francisco. Sgt. Pepper was played in kiosks and stands there, and festival staff wore badges carrying Lennon’s lyric “A splendid time is guaranteed for all”.

American radio stations interrupted their regular scheduling, playing the album virtually non-stop, often from start to finish. Emphasising its identity as a self-contained work, none of the songs were issued as singles at the time or available on spin-off EPs. Instead, the Beatles released “All You Need Is Love” as a single in July, after performing the song on the Our World satellite broadcast on 25 June before an audience estimated at 400 million. According to sociomusicologist Simon Frith, the international broadcast served to confirm “the Beatles’ evangelical role” amid the public’s embrace of Sgt. Pepper. In the UK, Our World also quelled the furore that followed McCartney’s repeated admission in mid-June that he had taken LSD. In Norman’s description, this admission was indicative of how “invulnerable” McCartney felt after Sgt. Pepper; it made the band’s drug-taking public knowledge and confirmed the link between the album and drugs.

Commercial performance

Sgt. Pepper topped the Record Retailer albums chart (now the UK Albums Chart) for 23 consecutive weeks from 10 June, with a further four weeks at number one in the period through to February 1968. The record sold 250,000 copies in the UK during its first seven days on sale there. The album held the number one position on the Billboard Top LPs chart in the US for 15 weeks, from 1 July to 13 October 1967, and remained in the top 200 for 113 consecutive weeks. It also topped charts in many other countries.

With 2.5 million copies sold within three months of its release, Sgt. Pepper‘s initial commercial success exceeded that of all previous Beatles albums. In the UK, it was the best-selling album of 1967 and of the decade. According to figures published in 2009 by former Capitol executive David Kronemyer, further to estimates he gave in MuseWire magazine, the album had sold 2,360,423 copies in the US by 31 December 1967 and 3,372,581 copies by the end of the decade.

Contemporary critical reception

The release of Sgt. Pepper coincided with a period when, with the advent of dedicated rock criticism, commentators sought to recognise artistry in pop music, particularly in the Beatles’ work, and identify albums as refined artistic statements. In America, this approach had been heightened by the “Strawberry Fields Forever” / “Penny Lane” single, and was also exemplified by Leonard Bernstein’s television program Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution, broadcast by CBS in April 1967. Following the release of the Beatles’ single, in author Bernard Gendron’s description, a “discursive frenzy” ensued as Time, Newsweek and other publications from the cultural mainstream increasingly voiced their “ecstatic approbation toward the Beatles”.

The vast majority of contemporary reviews of Sgt. Pepper were positive, with the album receiving widespread critical acclaim. Schaffner said that the consensus was aptly summed up by Tom Phillips in The Village Voice, when he called the LP “the most ambitious and most successful record album ever issued”. Among Britain’s pop press, Peter Jones of Record Mirror said the album was “clever and brilliant, from raucous to poignant and back again”, while Disc and Music Echo‘s reviewer called it “a beautiful and potent record, unique, clever, and stunning”. In The Times, William Mann described Sgt. Pepper as a “pop music master-class” and commented that, so considerable were its musical advances, “the only track that would have been conceivable in pop songs five years ago” was “With a Little Help from My Friends”. Having been among the first British critics to fully appreciate Revolver, Peter Clayton of Gramophone magazine said that the new album was “like nearly everything the Beatles do, bizarre, wonderful, perverse, beautiful, exciting, provocative, exasperating, compassionate and mocking”. He found “plenty of electronic gimmickry on the record” before concluding: “but that isn’t the heart of the thing. It’s the combination of imagination, cheek and skill that make this such a rewarding LP.” Wilfrid Mellers, in his review for New Statesman, praised the album’s elevation of pop music to the level of fine art, while Kenneth Tynan, The Times‘ theatre critic, said it represented “a decisive moment in the history of Western civilisation”. Newsweek‘s Jack Kroll called Sgt. Pepper a “masterpiece” and compared its lyrics with literary works by Edith Sitwell, Harold Pinter and T. S. Eliot, particularly “A Day in the Life”, which he likened to Eliot’s The Waste Land. The New Yorker paired the Beatles with Duke Ellington, as artists who operated “in that special territory where entertainment slips into art”.

One of the few well-known American rock critics at the time, and another early champion of Revolver, Richard Goldstein wrote a scathing review in The New York Times. He characterised Sgt. Pepper as a “spoiled” child and “an album of special effects, dazzling but ultimately fraudulent”, and was critical of the Beatles for sacrificing their authenticity to become “cloistered composers”. Although he admired “A Day in the Life”, comparing it to a work by Wagner, Goldstein said that the songs lacked lyrical substance such that “tone overtakes meaning”, an aesthetic he blamed on “posturing and put-on” in the form of production effects such as echo and reverb. As a near-lone voice of dissent, he was widely castigated for his views. Four days later, The Village Voice, where Goldstein had become a celebrated columnist since 1966, reacted to the “hornet’s nest” of complaints, by publishing Phillips’ highly favourable review. According to Schaffner, Goldstein was “kept busy for months” justifying his opinions, which included writing a defence of his review, for the Voice, in July.

Among the commentators who responded to Goldstein’s critique, composer Ned Rorem, writing in The New York Review of Books, credited the Beatles with possessing a “magic of genius” akin to Mozart and characterised Sgt. Pepper as a harbinger of a “golden Renaissance of Song”. Time quoted musicologists and avant-garde composers who equated the standard of the Beatles’ songwriting to Schubert and Schumann, and located the band’s work to electronic music; the magazine concluded that the album was “a historic departure in the progress of music – any music”. Literary critic Richard Poirier wrote a laudatory appreciation of the Beatles in the journal Partisan Review and said that “listening to the Sgt. Pepper album one thinks not simply of the history of popular music but the history of this century.” In his December 1967 column for Esquire, Robert Christgau described Sgt. Pepper as “a consolidation, more intricate than Revolver but not more substantial”. He suggested that Goldstein had fallen “victim to overanticipation”, identifying his primary error as “allow[ing] all the filters and reverbs and orchestral effects and overdubs to deafen him to the stuff underneath, which was pretty nice”.

Sociocultural influence – Contemporary youth and counterculture

In the wake of Sgt. Pepper, the underground and mainstream press widely publicised the Beatles as leaders of youth culture, as well as “lifestyle revolutionaries”. In Moore’s description, the album “seems to have spoken (in a way no other has) for its generation”. An educator referenced in a July 1967 New York Times article was reported to have said on the topic of music studies and its relevance to the day’s youth: “If you want to know what youths are thinking and feeling … you cannot find anyone who speaks for them or to them more clearly than the Beatles.”

Sgt. Pepper was the focus of much celebration by the counterculture. American Beat poet Allen Ginsberg said of the album: “After the apocalypse of Hitler and the apocalypse of the Bomb, there was here an exclamation of joy, the rediscovery of joy and what it is to be alive.” The American psychologist and counterculture figure Timothy Leary labelled the Beatles “avatars of the new world order” and said that the LP “gave a voice to the feeling that the old ways were over” by stressing the need for cultural change based on a peaceful agenda. According to author Michael Frontani, the Beatles “legitimiz[ed] the lifestyle of the counterculture”, just as they did popular music, and formed the basis of Jann Wenner’s scope on these issues when launching Rolling Stone magazine in late 1967. Further to Lennon wearing an Afghan sheepskin coat at the album launch party, “Afghans” became a popular garment among hippies, and Westerners increasingly sought out the coats on the hippie trail in Afghanistan.

McCartney’s LSD admission formalised the link between rock music and drugs, and attracted scorn from American religious leaders and conservatives. Vice-president Spiro Agnew contended that the “friends” referred to in “With a Little Help from My Friends” were “assorted drugs”. As part of an escalating national debate that triggered an investigation by the US Congress, he launched a campaign in 1970 to address the issue of American youth being “brainwashed” into taking drugs through the music of the Beatles and other rock artists. In the UK, according to historian David Simonelli, the album’s obvious drug allusions inspired a hierarchy within the youth movement for the first time, based on listeners’ ability to “get” psychedelia and align with the elite notion of Romantic artistry. Harrison was eager to separate the message of “Within You Without You” from the LSD experience, telling an interviewer: “It’s nothing to do with pills … It’s just in your own head, the realisation.”

The Beatles’ presentation as Sgt. Pepper’s band resonated at a time when many young people in the UK and the US were seeking to redefine their own identity and were drawn to communities that espoused the transformational power of mind-altering drugs. In the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco, the recognised centre of the counterculture, Sgt. Pepper was viewed as a “code for life”, according to music journalist Alan Clayson, with street people such as the Merry Band of Pranksters offering “Beatle readings”. American social activist Abbie Hoffman credited the album as his inspiration for staging the attempted levitation of the Pentagon during the Mobe’s anti-Vietnam War rally in October 1967. The Byrds’ David Crosby later expressed surprise that by 1970 the album’s powerful sentiments had not been enough to stop the Vietnam War.

Sgt. Pepper informed Frank Zappa’s parody of the counterculture and flower power on the Mothers of Invention’s 1968 album We’re Only in It for the Money. By 1968, according to music critic Greil Marcus, Sgt. Pepper appeared shallow against the emotional backdrop of the political and social upheavals of American life. Simon Frith, in his overview of 1967 for The History of Rock, said that Sgt. Pepper “defined the year” by conveying the optimism and sense of empowerment at the centre of the youth movement. He added that the Velvet Underground’s The Velvet Underground & Nico – an album that contrasted sharply with the Beatles’ message by “offer[ing] no escape” – became more relevant in a cultural climate typified by “the Sex Pistols, the new political aggression, the rioting in the streets” during the 1970s. In a 1987 review for Q magazine, Charles Shaar Murray asserted that Sgt. Pepper “remains a central pillar of the mythology and iconography of the late ’60s”, while Colin Larkin states in his 1989 Encyclopedia of Popular Music: “[it] turned out to be no mere pop album but a cultural icon, embracing the constituent elements of the 60s’ youth culture: pop art, garish fashion, drugs, instant mysticism and freedom from parental control.”

Sociocultural influence – Cultural legitimisation of popular music

In The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature, Kevin Dettmar writes that Sgt. Pepper achieved “a combination of popular success and critical acclaim unequaled in twentieth-century art … never before had an aesthetic and technical masterpiece enjoyed such popularity.” Through the level of attention it received from the rock press and more culturally elite publications, the album achieved full cultural legitimisation for pop music and recognition for the medium as a genuine art form. Riley says that pop had been due this accreditation “at least as early as A Hard Day’s Night” in 1964. He adds that the timing of the album’s release and its reception ensured that “Sgt. Pepper has attained the kind of populist adoration that renowned works often assume regardless of their larger significance – it’s the Beatles’ ‘Mona Lisa’.” At the 10th Annual Grammy Awards in March 1968, Sgt. Pepper won awards in four categories: Album of the Year; Best Contemporary Album; Best Engineered Recording, Non-Classical; and Best Album Cover, Graphic Arts. Its win in the Album of the Year category marked the first time that a rock LP had received this honour.

Among the recognised composers who helped legitimise the Beatles as serious musicians at the time were Luciano Berio, Aaron Copland, John Cage, Ned Rorem and Leonard Bernstein. According to Rodriguez, an element of exaggeration accompanied some of the acclaim for Sgt. Pepper, with particularly effusive approbation coming from Rorem, Bernstein and Tynan, “as if every critic was seeking to outdo the other for the most lavish embrace of the Beatles’ new direction”. In Gendron’s view, the cultural approbation represented American “highbrow” commentators (Rorem and Poirier) looking to establish themselves over their “low-middlebrow” equivalent, after Time and Newsweek had led the way in recognising the Beatles’ artistry, and over the new discipline of rock criticism. Gendron describes the discourse as one whereby, during a period that lasted for six months, “highbrow” composers and musicologists “jostl[ed] to pen the definitive effusive appraisal of the Beatles”.