Friday, February 3, 1967

Recording "A Day In The Life" #3

For The Beatles

Last updated on July 17, 2024

Friday, February 3, 1967

For The Beatles

Last updated on July 17, 2024

Recording "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band"

Nov 24, 1966 - Apr 20, 1967 • Songs recorded during this session appear on Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (UK Mono)

Recording studio: EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Interview February 1967 • The Beatles interview for The Beatles Monthly Book

Session Feb 02, 1967 • Recording "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band"

Session Feb 03, 1967 • Recording "A Day In The Life" #3

Article Feb 05, 1967 • Paul McCartney attends a concert by Cream

Film Feb 05 and 07, 1967 • Shooting of "Penny Lane" promo film

Next session Feb 08, 1967 • Recording "Good Morning Good Morning"

Some of the songs worked on during this session were first released on the "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (UK Mono)" LP.

The Beatles had recorded “A Day In The Life” in two sessions so far, on January 19 and January 20, 1967. On this day, they continued working on the track during a session that lasted from 7 pm to 1:15 am. During this session, all the overdubs recorded involved replacing previously-recorded parts.

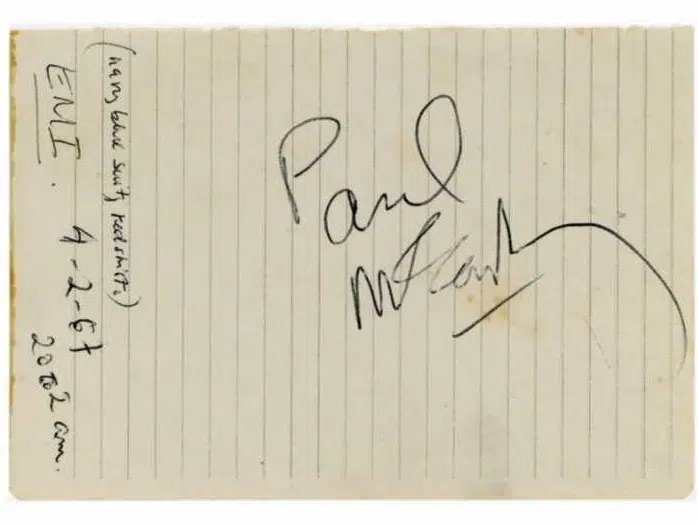

First, Paul McCartney replaced the vocals he had recorded on January 20 on track three of the four-track tape.

The first task there was to replace Paul’s guide vocal in the middle section, and he and I had a long discussion about that, which led to another sonic innovation. He explained that he wanted his voice to sound all muzzy, as if he had just woken up from a deep sleep and hadn’t yet gotten his bearings, because that was what the lyric was trying to convey. My way of achieving that was to deliberately remove a lot of the treble from his voice and heavily compress it to make him sound muffled. When the song goes into the next section, the dreamy section that John sings, the full fidelity is restored.

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

Recording and editing Paul’s vocals proved to be a challenging task for second engineer Richard Lush, who had recently been recruited to work on The Beatles’ sessions, as explained by Geoff Emerick:

Paul’s vocal…was being dropped into the same track that contained John’s lead vocal, and there was a very tight drop-out point between the two – between Paul’s singing ‘…and I went into a dream’ and John’s ‘ahhh’ that starts the next section. Richard was quite paranoid about it – with good reason – and I remember him asking me to get on the talkback mic to explain the situation to Paul and ask him not to deviate from the phrasing that he had used on the guide vocal.

I was really impressed when Richard [Lush] did that – I thought it showed great maturity to be proactive that way. John’s vocal, after all, had such great emotion, and it also had tape echo on it. The thought of having to do it again and re-create the atmosphere was daunting…not to mention what John’s reaction would have been! Someone’s head would have been bitten off, and it most likely would have been mine. But Paul, ever professional, did heed the warning, and he made certain to end the last word distinctly in order to give Richard sufficient time to drop out before John’s vocal came back in. Listening carefully, you can actually hear Paul slightly rush the vocal; he even adds a little ‘ah’ to the end of the word ‘dream,’ giving it a very clipped ending.

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

After that, Paul and Ringo Starr re-recorded the bass and drum parts they had recorded on January 20. They were joined by John Lennon on the tambourine and George Harrison on the maracas. All those superimpositions were recorded on track four.

We persuaded Ringo to play tom-toms. It’s sensational. He normally didn’t like to play lead drums, as it were, but we coached him through it. We said, “Come on, you’re fantastic, this will be really beautiful,” and indeed it was.

Paul McCartney – From “Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now” by Barry Miles, 1997

We now returned our attention to the main section of the song. At that point, the rhythmic accompaniment still consisted solely of Ringo’s maracas and just the slightest trace of George Harrison on bongos, and John felt strongly that more was needed. Paul suggested that Ringo not just do his normal turn but really cut loose on the track, and I could see that the drummer was quite reticent. “Come on, Paul, you know how much I hate flashy drumming,” he complained, but with John and Paul coaching and egging him on, he did an overdub that was nothing short of spectacular, featuring a whole series of quirky tom-tom fills.

Because John and Paul felt so strongly that the drums be featured in this song. I decided to experiment sonically as well. We were looking for a thicker, more tonal quality, so I suggested that Ringo tune his toms really low, making the skins really slack, and I also added a lot of low end at the mixing console. That made them sound almost like timpani, but I still felt there was more I could do to make his playing stand out. During the making of ‘Revolver,’ I had removed the front skin from Ringo’s bass drum and everyone was pleased with the resultant sound, so I decided to extend that principle and take off the bottom heads from the tom-toms as well, miking them from underneath. We had no boom stands that could extend underneath the floor tom, so I simply wrapped the mic in a towel and placed it in a glass jug on the floor. For the icing on the cake, I decided to overly limit the drum premix, which made the cymbals sound huge. It took a lot of work and effort, but that’s one drum sound I was extremely proud of, and Ringo, who was always meticulous about his sounds, loved it, too.

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

At some point during the session, the decision was made to use a symphony orchestra to fill the gap between the two sections of the track.

It was at that session that a decision was finally reached about what to do to fill in the twenty-four empty bars between the main part of the song and Paul’s new middle section. John had an idea — abstract, as usual — about creating some kind of sound that would start out really tiny and then gradually expand to become huge and all-engulfing. Picking up on the theme, Paul excitedly suggested employing a full symphony orchestra. George Martin liked the idea, but, mindful of the cost, was adamant that there was no way he could justify charging EMI for a full ninety-piece orchestra just to play twenty-four bars of music. It was Ringo, of all people, who came up with the solution. “Well, then,” he joked, “let’s just hire half an orchestra and have them play it twice.” Everyone did a double take, stunned by the simplicity — or was it simple-mindedness? — of the suggestion.

“You know, Ring, that’s not a bad idea,” Paul said.

“But still, boys, think of the cost…” George Martin stammered.

Lennon put an end to the discussion. “Right, Henry,” he said, his voice carrying the tone of an emperor issuing a decree. “Enough chitchat. Let’s do it.”

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

The question was, how were we going to fill those twenty-four bars of emptiness? After all, it was pretty boring! So I asked John for his ideas. As always, it was a matter of my trying to get inside his mind, discover what pictures he wanted to paint, and then try to realise them for him. He said: ‘What I’d like to hear is a tremendous build-up, from nothing up to something absolutely like the end of the world. I’d like it to be from extreme quietness to extreme loudness, not only in volume, but also for the sound to expand as well. I’d like to use a symphony orchestra for it. Tell you what, George, you book a symphony orchestra, and we’ll get them in a studio and tell them what to do.’

‘Come on, John,’ I said, ‘there’s no way you can get a symphony orchestra sitting around and say to them, “Look, fellers, this is what you’re going to do.” Because you won’t get them to do what you want them to do. You’ve got to write something down for them.’

‘Why?’ asked John, with his typically wide-eyed approach to such matters.

‘Because they’re all playing different instruments, and unless you’ve got time to go round each of them individually and see exactly what they do, it just won’t work.’

But he did explain what he wanted sufficiently for me to be able to write a score. For the ‘I’d like to turn you onnnnnnnn…’ bit, I used cellos and violas. I had them playing those two notes that echo John’s voice. However, instead of fingering their instruments, which would produce crisp notes, I got them to slide their fingers up and down the frets, building in intensity until the start of the orchestral climax.

That climax was something else again. What I did there was to write, at the beginning of the twenty-four bars, the lowest possible note for each of the instruments in the orchestra. At the end of the twenty-four bars, I wrote the highest note each instrument could reach that was near a chord of E major. Then I put a squiggly line right through the twenty-four bars, with reference points to tell them roughly what note they should have reached during each bar. The musicians also had instructions to slide as gracefully as possible between one note and the next. In the case of the stringed instruments, that was a matter of sliding their fingers up the strings. With keyed instruments, like clarinet and oboe, they obviously had to move their fingers from key to key as they went up, but they were asked to ‘lip’ the changes as much as possible too.

I marked the music ‘pianissimo’ at the beginning and ‘fortissimo’ at the end. Everyone was to start as quietly as possible, almost inaudibly, and end in a (metaphorically) lung-bursting tumult. And in addition to this extraordinary of musical gymnastics, I told them that they were to disobey the most fundamental rule of the orchestra. They were not to listen to their neighbours.

A well-schooled orchestra plays, ideally, like one man, following the leader. I emphasised that this was exactly what they must not do. I told them ‘I want everyone to be individual. It’s every man for himself. Don’t listen to the fellow next to you. If he’s a third away from you, and you think he’s going too fast, let him go. Just do your own slide up, your own way.’ Needless to say, they were amazed. They had certainly never been told that before.

To perform this little extravagance, John and Paul. had asked me for a full symphony orchestra. But although by then I had grown used to pretty lavish outlays where the Beatles were concerned, my sense of EMI-induced caution had not entirely deserted me. So I said: ‘With all due respect, I think it’s a bit silly booking ninety musicians just to get an eff’ect like this.’ So I settled on half a symphony orchestra, with one flute, one oboe, one bassoon, one clarinet and so on, instead of two of each. We ended up with forty-two players.

George Martin – From “All You Need Is Ears“, 1979

The orchestra overdubs were recorded on February 10, 1967, giving John, Paul, and George Martin the time to work out exactly what they wanted to achieve.

First we wrote out the music for the part where the orchestra had proper chords to do: after ‘Somebody spoke and I went into a dream …’ big pure chords come in. But for the other orchestral parts I had a different idea. I sat John down and suggested it to him and he liked it a lot. I said, ‘Look, all these composers are doing really weird avant-garde things and what I’d like to do here is give the orchestra some really strange instructions. We could tell them to sit there and be quiet, but that’s been done, or we could have our own ideas based on this school of thought. This is what’s going on now, this is what the movement’s about.’ So this is what we did.

I said, ‘Right, to save all the arranging, we’ll take the whole orchestra as one instrument.’ And I wrote it down like a cooking recipe: I told the orchestra, “There are twenty-four empty bars; on the ninth bar, the orchestra will take off, and it will go from its lowest note to its highest note. You start with the lowest note in the range of your instrument, and eventually go through all the notes of your instrument to the highest note. But the speed at which you do it is your own choice. You’ve got to get from your lowest to your highest. You don’t have to actually use all your notes but you’ve got to do those two, that’s the only restriction.’ So that was the brief, a little avant-garde brief.

Paul McCartney – From “Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now” by Barry Miles, 1997

“I think it would be great if we ask each member of the orchestra to play randomly,” Paul suggested.

George Martin was aghast. “Randomly? That will just sound like a cacophony; it’s pointless.”

“Okay, well then, not completely randomly,” Paul replied. “Maybe we could get each of them to do a slow climb from the lowest note their instrument can play up to the highest note.”

“Yeah,” interjected John, “and also have them start really quietly and get louder and louder, so that it eventually becomes an orgasm of sound.”

George Martin still looked dubious. “The problem,” he explained, “is that you can’t ask classical musicians of that caliber to improvise and not follow a score—they’ll simply have no idea what to do.”

John seemed lost in thought for a moment, and then brightened up. “Well, if we put them in silly party hats and rubber noses, maybe then they’ll understand what it is we want. That will loosen up those tight-asses!”

I thought it was a brilliant idea. The idea was to get them into the spirit of things, to create a party atmosphere, a sense of camaraderie. John was not seeking to necessarily embarrass them or make them look silly—he was actually trying to tear down the barrier that had existed between classical and pop musicians for years.

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

John said, ‘I want it to be like a musical orgasm. I want it to start from absolutely nothing and increase in tremendous tension and build up to the most overpowering sound you’ve ever heard in your life.’ So, I actually did a score and the beginning note in each case was the lowest note for every instrument, and the highest note they could manage within a particular E major chord. I also gave them mileposts every bar, so they could refer to wherever they were going to go. I told them, ‘You must not listen to each other. You’ve got to make your own way from the bottom note to the top, without listening to the fellow sitting next to you.’

George Martin – From “The Beatles: Off the Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

Recording • SI onto take 6

The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions • Mark Lewisohn

The definitive guide for every Beatles recording sessions from 1962 to 1970.

We owe a lot to Mark Lewisohn for the creation of those session pages, but you really have to buy this book to get all the details - the number of takes for each song, who contributed what, a description of the context and how each session went, various photographies... And an introductory interview with Paul McCartney!

The Beatles Recording Reference Manual: Volume 3: Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band through Magical Mystery Tour (late 1966-1967)

The third book of this critically - acclaimed series, nominated for the 2019 Association for Recorded Sound Collections (ARSC) award for Excellence In Historical Recorded Sound, "The Beatles Recording Reference Manual: Volume 3: Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band through Magical Mystery Tour (late 1966-1967)" captures the band's most innovative era in its entirety. From the first take to the final remix, discover the making of the greatest recordings of all time. Through extensive, fully-documented research, these books fill an important gap left by all other Beatles books published to date and provide a unique view into the recordings of the world's most successful pop music act.

If we modestly consider the Paul McCartney Project to be the premier online resource for all things Paul McCartney, it is undeniable that The Beatles Bible stands as the definitive online site dedicated to the Beatles. While there is some overlap in content between the two sites, they differ significantly in their approach.

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.