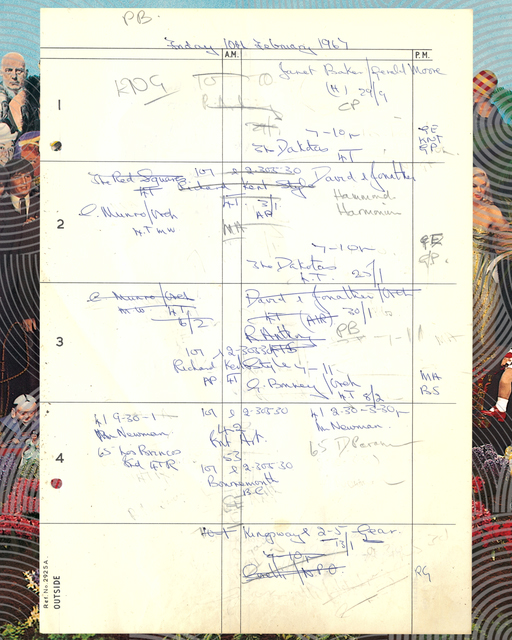

Friday, February 10, 1967

Recording "A Day In The Life" #4

For The Beatles

Last updated on May 4, 2024

Friday, February 10, 1967

For The Beatles

Last updated on May 4, 2024

Recording "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band"

Nov 24, 1966 - Apr 20, 1967 • Songs recorded during this session appear on Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (UK Mono)

Recording studio: EMI Studios, Studio One, Abbey Road

Session Feb 08, 1967 • Recording "Good Morning Good Morning"

Session Feb 09, 1967 • Recording "Fixing A Hole"

Session Feb 10, 1967 • Recording "A Day In The Life" #4

Film Feb 10, 1967 • Shooting of "A Day In The Life" promo film

Session Feb 13, 1967 • Mixing "A Day In The Life", recording "Only A Northern Song"

Some of the songs worked on during this session were first released on the "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (UK Mono)" LP.

The Beatles had recorded “A Day In The Life” in three sessions so far, on January 19, January 20 and February 3, 1967. During this latter session, The Beatles decided to use a symphony orchestra to fill the 24-bar gap between the two sections of the track. To allay concerns that classically trained musicians would not be able to improvise the section, producer George Martin wrote a loose score for the section. It was an extended, atonal crescendo that encouraged the musicians to improvise within the defined framework.

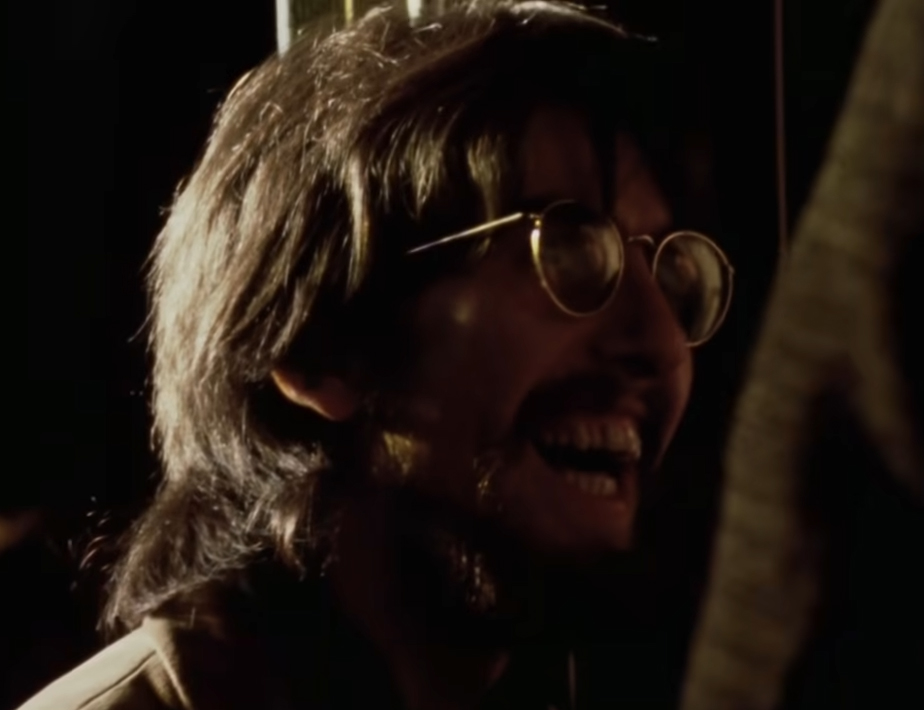

The orchestra overdubs were recorded on this day, between 8 pm to 1 am, with George Martin and Paul McCartney conducting a 40-piece orchestra. The session was completed at a total cost of £367 for the players, an extravagance at the time.

Also present in the studio was George Harrison’s wife Pattie, along with a number of friends including Mick Jagger, Marianne Faithfull, Keith Richards, Donovan, Michael Nesmith of The Monkees, Pete Shotton, and Simon Posthuma and Marijke Koger of design company The Fool.

Once we’d written the main bit of the music, we thought, now look, there’s a little gap there and we said oh, how about an orchestra? Yes, that’ll be nice. And if we do have an orchestra, are we going to write them a pseudo-classical thing, which has been done better by people who know how to make it sound like that – or are we going to do it like we write songs? Take a guess and use instinct. So we said, right, what we’ll do to save all the arranging, we’ll take the whole orchestra as one instrument. And we just wrote it down like a cooking recipe: 24 bars; on the ninth bar, the orchestra will take off, and it will go from its lowest note to its highest note.

From “The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years” by Barry Miles

A little later that evening, Paul had another brainstorm: “Let’s make the session more than just a session: let’s make it a happening.”

Lennon loved the idea. “We’ll invite all our friends, and everyone will have to come in fancy dress costume,” he enthused. “That includes you lot, too,” he said pointedly to Richard [Lust] and me.

George Martin smiled paternally. “Well, I can certainly ask the orchestra to wear their tuxedos, though there may be an extra cost involved.”

“Sod the cost,” John said. “We’re making enough bloody money for EMI that they can spring for it… and for the party favors, too.”

To gales of laughter from the others, Lennon began reeling off a list of what he wanted Mal to purchase at the novelty store: silly hats, rubber noses, clown wigs, bald head pates, gorilla paws . . . and lots of clip-on nipples.

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

There are so many great memories at Abbey Road. It’s very hard to choose one, but just to pick out of the bunch, I think it was recording the orchestra on ‘A Day In The Life’.

Paul McCartney

The orchestra and George Martin had been asked to attend in full evening dress, which the Beatles also promised they would wear. The Beatles did not keep their word but the orchestra and George Martin looked very smart in their tuxedos. In order to get them into the mood to play something unconventional and to encourage in them an element of playful spontaneity, the Beatles went among the players handing out party favours. Mal Evans had been sent to a joke shop on Great Russell Street and returned with plastic stick-on nipples, plastic glasses with false eyes, rubber bald pates, some with knotted handkerchiefs balanced on them, huge fake cigars, party hats and streamers: David McCallum, the leader of the London Philharmonic, wore a large red false nose; Erich Gruenberg, the leader of the second violins, had on a pair of flowery paper spectacles and held his bow in a large gorilla paw; the bassoon players, Alfred Waters and N. Fawcett, had balloons attached to their instruments which inflated and deflated with each note, raising a laugh from George Martin.

From “Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now” by Barry Miles, 1997

We all felt a sense of occasion, since it was the largest orchestra we ever used on a Beatles recording. So I wasn’t all that surprised when Paul rang up and said, ‘Look, do you mind coming in evening dress?’

‘Why? What’s the idea?’

‘We thought we’d have fun. We’ve never had a big orchestra before, so we thought we’d have fun on the night. So will you come in evening dress? And I’d like all the orchestra to come in evening dress, too.’

‘Well, that may cost a bit extra, but we’ll do it,’ I said. ‘What are you going to wear?’

‘Oh, our usual freak-outs’ – by which he meant their gaudy hippie clothes, floral coats and all.

Came the night, and I discovered that they’d also invited along all their way-out friends, like Mick Jagger, Marianne Faithfull, and Simon and Marijke, the psychedelic artists who were running the Apple shop in Baker Street. They were wandering in and out of the orchestra, passing out sparklers and joints and God knows what, and on top of that they had brought along a mass of party novelties.

After one of the rehearsals I went into the control room to consult Geoff Emerick. When I went back into the studio the sight was unbelievable. The orchestra leader, David McCallum, who used to be the leader of the Royal Philharmonic, was sitting there in a bright red false nose. He looked up at me through paper glasses. Eric Gruenberg, now a soloist and once leader of the BBC Symphony Orchestra, was playing happily away, his left hand perfectly normal on the strings of his violin, but his bow held in a giant gorilla’s paw. Every member of the orchestra had a funny hat on above the evening dress, and the total effect was completely weird. Somewhere there is a film of the affair, taken by an Indian cameraman the Beatles knew.

The orchestra, of course, thought it was all a stupid giggle and a waste of money, but I think they were carried into the spirit of the party just because it was so ludicrous. […]

George Martin – From “All You Need Is Ears“, 1979

[The Beatles] invited us to the recording session party for “A Day in the Life” at the EMI studio on Abbey Road on February 10, 1967, which was to be released as a single June 1st. I danced around with sparkles and blowing bubbles enjoying myself very much, it was great fun. I have never been much of talker and Simon with his “gift of the gab” was always our spokesperson and interacted with the celebrity participants. After that we were commissioned to work on sketches for the Sgt. Pepper album cover.

Marijke Koger – From The Fool – From marijkekogerart.com, August 11, 2021

We chatted and drank champagne. We also had some of The Rolling Stones at the session, because we had a big session. We wanted to make a happening happen, and it happened.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles: Off the Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

On the appointed day, the 42-piece classically trained musicians filed into Abbey Road studios, their black bow ties and evening dress providing a striking contrast with The Beatles’ brightly coloured corduroys, floral shirts, and newly sprouted moustaches. Nonetheless, these gentlemen all seemed very keen to participate in this unusual meeting of cultures, and to give The Beatles the full benefit of their distinguished musicianship.

Pete Shotton – From “The Beatles: Off the Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

The leader of our 41-piece orchestra was David McCallum, who was the leader of one of the big orchestras in London and he was also the father of David McCallum, the co-star of the American TV series The Man From U.N.C.L.E.

George Martin – From “The Beatles: Off the Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

After setting up their music stands and tuning their instruments, the predominantly middle-aged visitors were each handed a paper mask or some other party novelty. The orchestra leader, for instance, was given a bright red false nose, while the main violinist was obliged to clutch his bow in a giant gorilla’s paw.

Pete Shotton – From “The Beatles: Off the Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

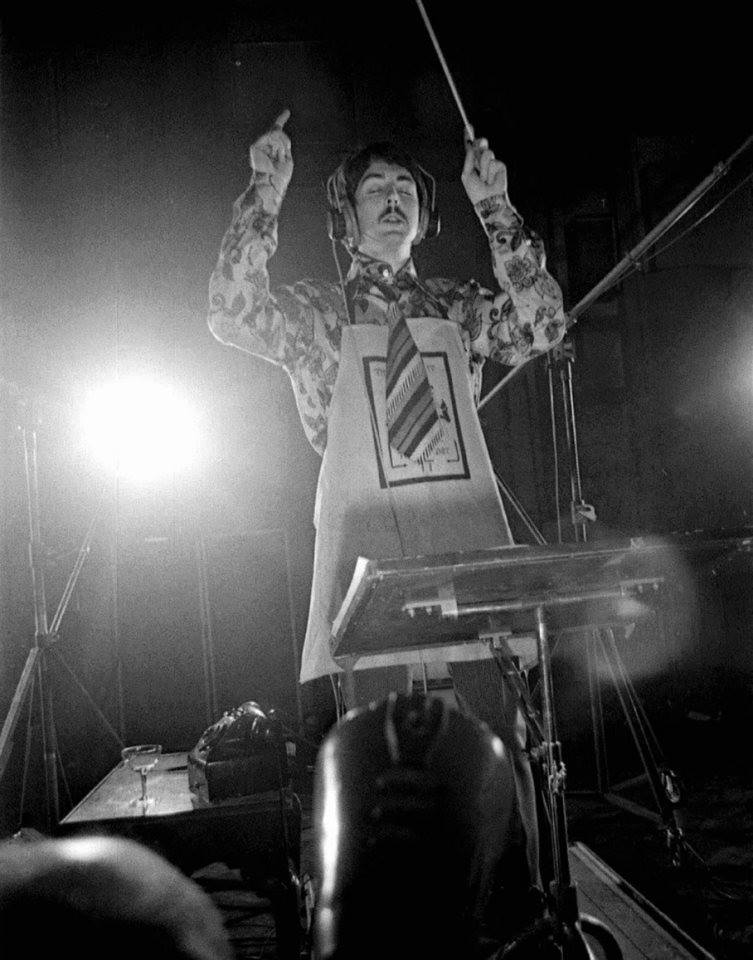

And if that wasn’t unorthodox enough, they were even more bemused, if not downright aghast, by Paul’s instructions that they all play as out of tune and out of time as possible. This twist was added during the taping of “A Day In The Life”‘s cosmic crescendo, for which Paul had assumed – with obvious relish – the role of “conductor.”

Pete Shotton – From “The Beatles, Lennon, And Me“, 1984

I felt initially embarrassed facing that sea of sessioners. So, I decided to treat them like human beings and not professional musicians. I tried to give myself to them.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles: Off the Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

It was quite a chaotic session. Such a big orchestra, playing with very little music. And the Beatle chaps were wandering around with rather expensive cameras, like new toys, photographing everything.

Alan Civil – Horn player – From “The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions” by Mark Lewisohn, 1988

Everybody would play their lowest note, say, and go up and play higher and higher. And you’d say “How the hell are they going to use this?” And there was Ringo dashing around with his movie camera. It seemed almost like a party, with booze, fags, and such. It was crazy. You couldn’t believe it was a session. A lot of classical musicians didn’t really condone this type of session. They thought it was rather beyond, well, beneath their dignity to mess around like that.

Alan Civil – From “The Unknown Paul McCartney: McCartney and the Avant-Garde” by Ian Peel, 2002

Only the Beatles could have assembled a studio full of musicians, many from the Royal Philharmonic or the London Symphony orchestras, all wearing funny hats, red noses, balloons on their bows and putting up with headphones clipped around their Stradivari violins acting as microphones.

Peter Vince, studio engineer – From “The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions” by Mark Lewisohn, 1988

I was speechless. the tempo changes – everything in that song – was just so dramatic and complete. I felt so privileged to be there… I walked out of the Abbey Road that night thinking ‘What am I going to do now?’ It really did affect me.

Tony Clark, studio engineer – From “The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions” by Mark Lewisohn

When we’d finished doing the orchestral bit one part of me said ‘We’re being a bit self indulgent here’. The other part of me said ‘It’s bloody marvellous!’

George Martin – From “The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions” by Mark Lewisohn

Work started with a tape reduction of Take 6 into Take 7, putting all previously recorded Beatles instruments and vocals onto track one of the four-track tape.

A separate tape reel was used to record the orchestra, which was running in parallel with Take 7. To enable this, technical engineer Ken Townsend had to devise a technical solution that allowed two four-track machines to run together. The separate tape reel made it possible to record the orchestra four times on each track of the four-track tape, creating the equivalent of 160 musicians.

The isolated orchestra recording was released in the 2017 “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” box set.

George Martin came up to me that morning and said to me ‘Oh Ken, I’ve got a poser for you. I want to run two four-track tape machines together this evening. I know it’s never been done before, can you do it?’ So I went away and came up with a method whereby we fed a 50 cycle tone from the track of one machine then raised its voltage to drive the capstan motor of the second, thus running the two in sync. Like all these things, the ideas either work first time or not at all. This one worked first time. At the session we ran the Beatles’ rhythm track on one machine, put an orchestral track on the second machine, ran it back did it again, and again, and again until we had four orchestra recordings. The only problem arose sometime later when George and I were doing a mix with two different machines. One of them was sluggish in starting up and we couldn’t get the damn things into sync. George got quite annoyed with me actually.

Ken Townsend, technical engineer – From “The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions” by Mark Lewisohn

In the end, of course, the ‘Day in the Life’ party was not a waste of money, because it produced an incredible piece of recorded sound. In fact, looking back on it, I think I should have been more extravagant and booked a full orchestra. But even so, I ended up with the equivalent of not one but two full orchestras. After rehearsal, we recorded that sound four times, and I added those four separate recordings to each other at slightly different intervals. If you listen closely you can hear the difference. They are not quite together.

That sound was used twice during the song. The first time, we ended it artificially, by literally splitting the tape, leaving silence. There is nothing more electrifying, after a big sound, than complete silence. The second time, of course, came at the end of the record, and for that I wanted a final chord, which we dubbed on later.

George Martin – From “All You Need Is Ears“, 1979

This orchestral session was filmed by a team led by Tony Bramwell from NEMS Enterprises for use in a planned television special. But given the BBC’s ban of “A Day In The Life“, because of what they assumed were drug references, the idea was abandoned. In 2015, portions of the film were released in the “A Day in the Life” promotional film, included in the three-disc versions of the Beatles’ 2015 video compilation 1+.

Remembering how, just after we decamped to London, by February 1967 when I was still twenty, I was directing the symphonic “A Day in the Life” on 35 mm film, the kind used for Hollywood movies. Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Donovan took turns with handheld cameras. That night at Abbey Road, a producer named George Martin would instruct the orchestra thus: “Start quiet, end loud.” […]

I clearly remember the filming of one of the final sessions for one of the tracks, “A Day in the Life,” when Mr. McCartney had arranged with Mr. Martin for a full orchestra, or as Paul described it, “a set of penguins” to play nothing while he, Mr. McCartney, conducted.

When I say play nothing, I mean no scored music. Paul wanted each instrument to play its own ascending scale in meter, leading up to a grand crescendo. Obviously it worked because you can hear it on the album. Before we filmed we handed out loaded 16mm cameras to invited guests including, among others, Mick and Marianne, and Mike Nesmith of the Monkees. They were shown what to press and told to film whatever they wanted. The BBC then banned the subsequent video. Not because of the content of the footage, but because the song itself had drug references.

Tony Bramwell – From “Magical Mystery Tours: My Life With The Beatles“, 2005

After the session musicians had completed their work and left, The Beatles considered how to end the song. The orchestral climax was felt to be too abrupt, so the group and the studio guests gathered around a microphone and recorded themselves humming a note lasting for eight beats.

The humming takes were numbered 8-11. The first three broke down as people could not stop themselves from laughing, but the final one was complete. Three more overdubs of humming were then added. This remained the ending for “A Day In The Life” until the final piano chord was recorded on February 22, 1967.

The humming takes 8-11 were released in the 2017 “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” box set.

Having done all the orchestral bit, we wanted something to finish off the song. When you reached that high note at the close of the orchestral sequence you were left hanging there; the song needed bringing sharply back down to earth. What we required, I thought, was a simple yet stunning chord. Something very, very loud, very resonant. But what would give us that resonance? I decided to try out a notion which went back to the recording of ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’: the ‘4000 monks’ ploy. I had always thought that the sound of a lot of people chanting a mantra was impelling and hypnotic. ‘Why don’t we make a chord of people singing, to make a noise like a gigantic tamboura?’ I suggested. ‘Get them to sing all the basic notes, with maybe a few fifths in between, and track them, over and over and over again, to give it depth?”

So we did that, and there is a tape of it at Abbey Road in the vaults. If I had had 4000 people available to sing, it might have worked. As it is, the noise that came out the other end is absolutely pathetic! I had eight or nine people, multiplied four or five times. Nobody had enough breath to hold the chord beyond about fifteen or twenty seconds, so it petered out, anyway, long before it shouldhave done.

George Martin – From “With A Little Help From My Friends: The Making of Sgt. Pepper“, 1995

After the orchestra left, Paul asked the other Beatles and their guests to stick around and try out an idea he had just gotten for an ending, something he wanted to overdub on after the final orchestral climax. Everyone was weary — the studio was starting to smell suspicously of pot, and there was lots of wine floating around — but they were keen to have a go. Paul’s concept was to have everyone hum the same note in unison; it was the kind of avant garde thinking he was doing a lot of in those days. It was absurd, really — the biggest gathering of pop stars in the world, gathered around a microphone, humming, with Paul conducting the choir. Though it never got used on the record, and most of the takes dissolved into laughter, it was a fun way to cap off a fine party.

It was well past midnight when everyone crowded into the tiny control room for one last playback, the overflow of guests spilling out into the corridor, listening through the open door. Everyone, without exception, was totally and utterly blown away by what they were hearing; Ron Richards kept shaking his head, telling anyone who would listen, “That’s it, Ithink I’ll give up and retire now.” But exhilarated as we all were, I could tell that GeorgeMartin was greatly relieved when the session finally ended—he had been stressed out all evening and I’m sure all he wanted to do was head home and get to bed.

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

Work on “A Day In The Life” continued on February 13 and February 22, 1967.

Tape copying • Tape reduction take 6 into take 7

Recording • SI onto take 7

Tape copying • Tape reduction take 7 with SI onto take 6

Editing • Edit piece takes 8-11

AlbumOfficially released on Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (50th anniversary boxset)

The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions • Mark Lewisohn

The definitive guide for every Beatles recording sessions from 1962 to 1970.

We owe a lot to Mark Lewisohn for the creation of those session pages, but you really have to buy this book to get all the details - the number of takes for each song, who contributed what, a description of the context and how each session went, various photographies... And an introductory interview with Paul McCartney!

The Beatles Recording Reference Manual: Volume 3: Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band through Magical Mystery Tour (late 1966-1967)

The third book of this critically - acclaimed series, nominated for the 2019 Association for Recorded Sound Collections (ARSC) award for Excellence In Historical Recorded Sound, "The Beatles Recording Reference Manual: Volume 3: Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band through Magical Mystery Tour (late 1966-1967)" captures the band's most innovative era in its entirety. From the first take to the final remix, discover the making of the greatest recordings of all time. Through extensive, fully-documented research, these books fill an important gap left by all other Beatles books published to date and provide a unique view into the recordings of the world's most successful pop music act.

If we modestly consider the Paul McCartney Project to be the premier online resource for all things Paul McCartney, it is undeniable that The Beatles Bible stands as the definitive online site dedicated to the Beatles. While there is some overlap in content between the two sites, they differ significantly in their approach.

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.