Tuesday, April 21-22, 1970

Interview for Evening Standard

Interview for the Evening Standard

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Last updated on August 18, 2022

Tuesday, April 21-22, 1970

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Last updated on August 18, 2022

Previous interview Apr 18, 1970 • Paul McCartney interview for Record Mirror

Article Apr 19, 1970 • "Maybe I'm Amazed" promotional video broadcast

Album Apr 20, 1970 • "McCartney" by Paul McCartney released in the US

Interview Tuesday, April 21-22, 1970 • Paul McCartney interview for Evening Standard

Article Apr 23, 1970 • "Let It Be" film is officially announced

Album Apr 24, 1970 • "Sentimental Journey" by Ringo Starr released in the US

Next interview Apr 25, 1970 • Paul McCartney interview for Disc And Music Echo

AlbumThis interview was made to promote the "McCartney" LP.

Officially appears on Let It Be (Limited Edition)

This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

We all have to ask each other’s permission before any of us does anything without the other three. My own record nearly didn’t come out because Klein and some of the others thought it would be too near to the date of the next Beatles album … I had to get George, who’s a director of Apple, to authorise its release for me. We’re all talking about peace and love but really, we’re not feeling peaceful at all.

Paul McCartney

This two-part interview was published on the April 21 and April 22, 1970 editions of the London Evening Standard.

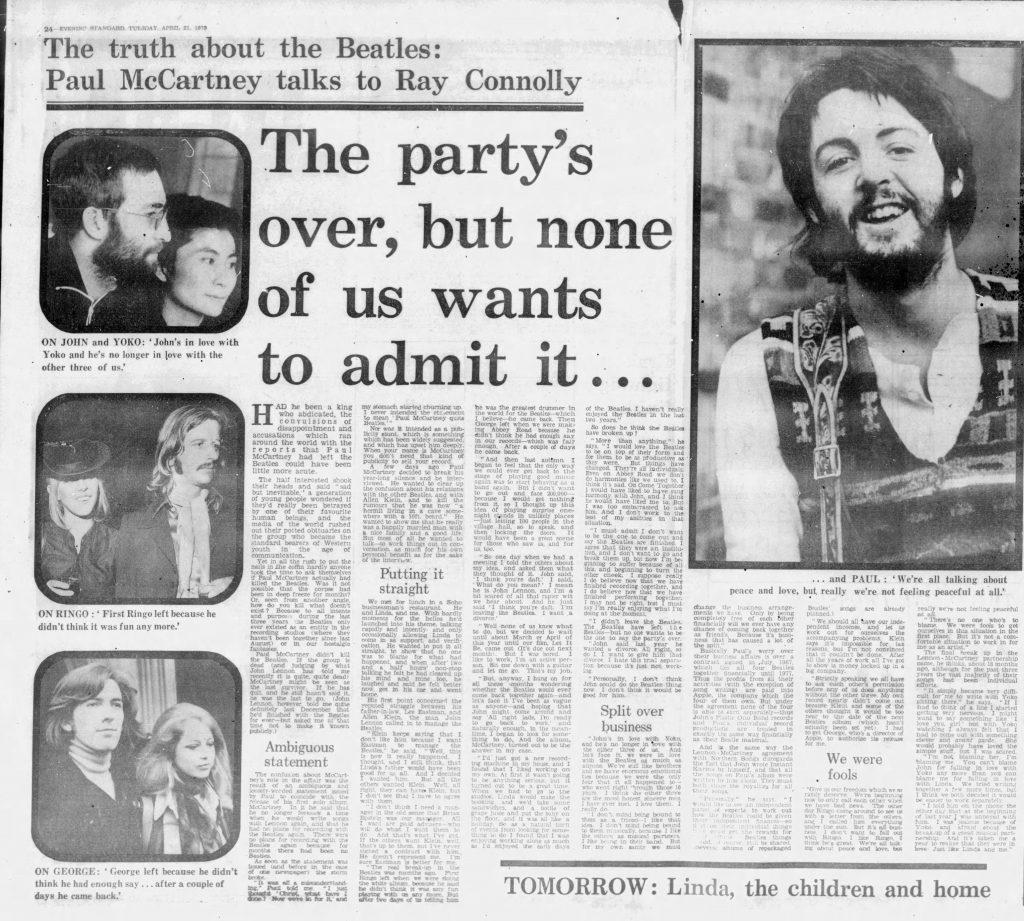

Had he been a king who had abdicated, the convulsions of disappointment and accusations which ran around the world with the reports that Paul McCartney had left the Beatles could not have been more acute.

The half-interested shook their heads and said ‘sad but inevitable’, a generation of young people wondered if they’d really been betrayed by one of their favourite human beings, and the media of the world rushed out their potted obituaries on the group who had become the standard bearers of Western youth in the age of communication.

Yet in the rush to put the nails in the coffin hardly anyone took the time to ask themselves if it really was Paul McCartney who had killed the Beatles. Was it not possible that the corpse had been in deep freeze for months? Or, seen from another angle, how do you kill what doesn’t exist? Because to all intents and purposes during the last three years the Beatles only ever existed as an entity in the recording studios (where they haven’t been together since last August) or in our nostalgic fantasies.

Paul McCartney didn’t kill the Beatles. If the group is dead, McCartney might be seen as the last survivor. If he has quit, and he still hasn’t confirmed it, he was the last to go.

The confusion about McCartney’s role in the affair was the result of an ambiguous and loosely-worded statement issued by Paul to coincide with the release of his solo album, McCartney. In it he said he no longer foresaw a time when he would write songs with Lennon again, and that he had no plans for recording with the Beatles. There were no plans for recording with the Beatles because for months there had been no Beatles.

But as soon as the statement was made public the storm broke.

‘It was all a misunderstanding,’ says Paul. ‘I just thought “Christ, what have I done? Now we’re in for it”, and my stomach started churning up. I never intended the statement to mean “Paul McCartney quits Beatles”.’ Nor, he says, was it intended as a publicity stunt, which is something that has been widely suggested, and which has upset him.

A few days ago Paul McCartney decided to break his year-long silence and be interviewed. He wanted to clear up the confusion about his relations with the other Beatles and Allen Klein, and to kill the rumours that he was now ‘a hermit living in a cave somewhere with a ten-foot beard’. He wanted to show that he really was a happily married man with ‘a nice family and a good life’. But most of all he wanted to talk, to work things out in conversation, as much, I suspect, for his own benefit as anything.

We met for lunch in a Soho businessman’s restaurant. With hardly moments for the hellos, he’d launched into his theme, talking rapidly and intently, and only occasionally allowing Linda to come in as support and verification. He wanted to put it all straight, to show that no one was to blame for what had happened, and when after two and a half hours’ non-stop talking he had cleared up his mind and mine too, he laughed, said he felt better now, got into his car and went home.

His first point concerned the reputed struggle between his father-in-law, Lee Eastman and Allen Klein.

‘Klein keeps saying that I don’t like him because I want Eastman to manage the Beatles,’ he said. ‘Well, this is how it really happened. I thought, and still think, that Linda’s father would have been good for us all. And I decided I wanted him. But all the others wanted Klein. Well, all right, they can have Klein, but I don’t see that I have to agree with them.

‘I don’t think I need a manager in the old sense that Brian Epstein was our manager. All I want are paid advisers, who will do what I want them to do. And that’s what I’ve got. If the others want Klein, well, that’s up to them, but I’ve never signed a contract with him. He doesn’t represent me. I’m sure Eastman is better for me.

‘The real break-up in the Beatles was months ago. First Ringo left when we were doing the White Album, because he said he didn’t think it was any fun playing with us any more. But after two days of us telling him he was the greatest drummer in the world for the Beatles, which I believe, he came back. Then George left when we were making Abbey Road because he didn’t think he had enough say in our records, which was fair enough. After a couple of days, he came back.

‘And then last autumn I began to feel that the only way we could ever get back to the stage of playing good music again was to start behaving as a band again. But I didn’t want to go out and face two hundred thousand fans because I would get nothing from it, so I thought up this idea of playing surprise one-night stands in unlikely places…just letting a hundred or so people in the village hall, so to speak, and then locking the doors. It would have been a great scene for those who saw us, and for us, too.

‘So, one day when we had a meeting I told the others about my idea, and asked them what they thought of it. John said, “I think you’re daft.” I said, “What do you mean?” I mean, he is John Lennon, and I’m a bit scared of all that rapier wit we hear about. And he just said again, “I think you’re daft. I’m leaving the Beatles. I want a divorce.”

‘Well, none of us knew what to do, but we decided to wait until about March or April of this year until our film, Let It Be, came out. But I was bored. I like to work, I’m an active person. Sit me down with a guitar and let me go. That’s my job.

‘Anyway, I hung on for all these months wondering whether the Beatles would ever come back together again…and let’s face it I’ve been as vague as anyone, hoping that John might come around and say, “All right lads, I’m ready to go back to work,” and naturally enough, in the meantime, I began to look for something to do. And the album, McCartney, turned out to be the answer in my case.

‘I’d just got a new recording machine in my house and I found that I liked working on my own. At first it wasn’t going to be anything serious, but it turned out to be a great time. When we had to go to the studios, Linda would make the booking, and we’d take some sandwiches, and a bottle of grape juice and put the baby on the floor, and it was all like a holiday. So, as a natural turn of events from looking for something to do, I found that I was enjoying working alone as much as I’d enjoyed the early days of the Beatles. I haven’t really enjoyed the Beatles in the last two years.’

So, does he think the Beatles have broken up?

‘More than anything,’ he says, ‘I would love the Beatles to be on top of their form and for them to be as productive as they were. But things have changed. We are all individuals. Even on Abbey Road we don’t do harmonies like we used to. I would have liked to have sung harmony with John, and I think he would have liked me to. But I was too embarrassed to ask him. And I don’t work to the best of my abilities in that situation.

‘I must admit, I don’t want to be the one to come out and say the Beatles are finished. I agree that they were an institution, and I don’t want to go and break them up, but now I’m beginning to suffer because of all this. I suppose, really, I do believe now that we have finished performing together, and I do believe now that we have finished recording together. I may not be right, but I must say I’m really enjoying what I’m doing at the moment.

‘I didn’t leave the Beatles. The Beatles have left the Beatles, but no one wants to be the one to say the party’s over. Last year John said he wanted a divorce. All right, so do I. I want to give him that divorce. I hate this trial separation because it’s just not working. Personally, I don’t think John could do the Beatles thing now. I don’t think it would be good for him.

‘John’s in love with Yoko, and he’s no longer in love with the other three of us. And let’s face it, we were in love with the Beatles as much as anyone. We’re still like brothers and we have enormous emotional ties because we were the only four that it all happened to…who went right through those ten years. I think the other three are the most honest, sincere men I have ever met. I love them. I really do.

‘I don’t mind being bound to them as a friend. I like that idea. I don’t mind being bound to them musically, because I like the others as musical partners. I like being in their band. But for my own sanity, we must change the business arrangements we have. Only by being completely free of each other financially will we ever have any chance of coming back together as friends. Because it’s business that has caused a lot of the split.’

Basically, Paul’s worry over their business affairs is over a contract signed in July, 1967, which ties all four Beatles together financially until 1977. Thus, the profits from all their activities (with the exception of song writing) are paid into Apple, the company that the four of them own. But under the agreement none of the four is able to earn separately, thus John’s Plastic Ono Band records and Paul’s individual record productions are treated in exactly the same way financially as their Beatle material. And, in the same way, the Lennon-McCartney agreement with Northern Songs disregards the fact that John wrote Instant Karma by himself, and that all the songs on Paul’s album were written by him alone. They must both share the royalties for all their songs.

‘Personally,’ he says, ‘I would like to see an independent panel of experts work out how the Beatles could be given their independent finances, so that on their individual things they could get the rewards for their efforts. Beatles things would, of course, still be shared.’

‘We should all have our independent incomes, and let us work out for ourselves the accompanying problems. Klein says it’s impossible for tax reasons, but I’m not convinced that it couldn’t be done. After all the years of work, all I’ve got to show is money locked up in a big company.

‘Strictly speaking we all have to ask each other’s permission before any of us does anything without the other three. My own record nearly didn’t come out because Klein and some of the others thought it would be too near to the date of the next Beatles album. I had to get George, who’s a director of Apple, to authorise its release for me.

‘Give us our freedom which we so richly deserve. We’re beginning now to only call each other when we have bad news. The other day Ringo came around to see me with a letter from the others, and I called him everything under the sun. But it’s all business. I don’t want to fall out with Ringo. I like Ringo. I think he’s great. We’re all talking about peace and love, but really we’re not feeling peaceful at all.

‘There’s no one who’s to blame. We were fools to get ourselves into this situation in the first place. But it’s not a comfortable situation for me to work in as an artist.’

The final break up in the Lennon-McCartney partnership came, he thinks, about eighteen months ago, although for the past three or four years the vast majority of their songs had been individual efforts.

‘It simply became very difficult for me to write with Yoko sitting there,’ he says. ‘If I had to think of a line I started getting very nervous. I might want to say something like “I love you, girl”, but with Yoko watching I always felt that I had to come out with something clever and avant-garde. She would probably have loved the simple stuff, but I was scared.

‘I’m not blaming her, I’m blaming me. You can’t blame John for falling in love with Yoko any more than you can blame me for falling in love with Linda. We tried writing together a few more times, but I think we both decided it would be easier to work separately.

‘I told John on the phone the other day that at the beginning of last year I was annoyed with him. I was jealous because of Yoko, and afraid about the break-up of a great musical partnership. It’s taken me a year to realise that they were in love. Just like Linda and me.’

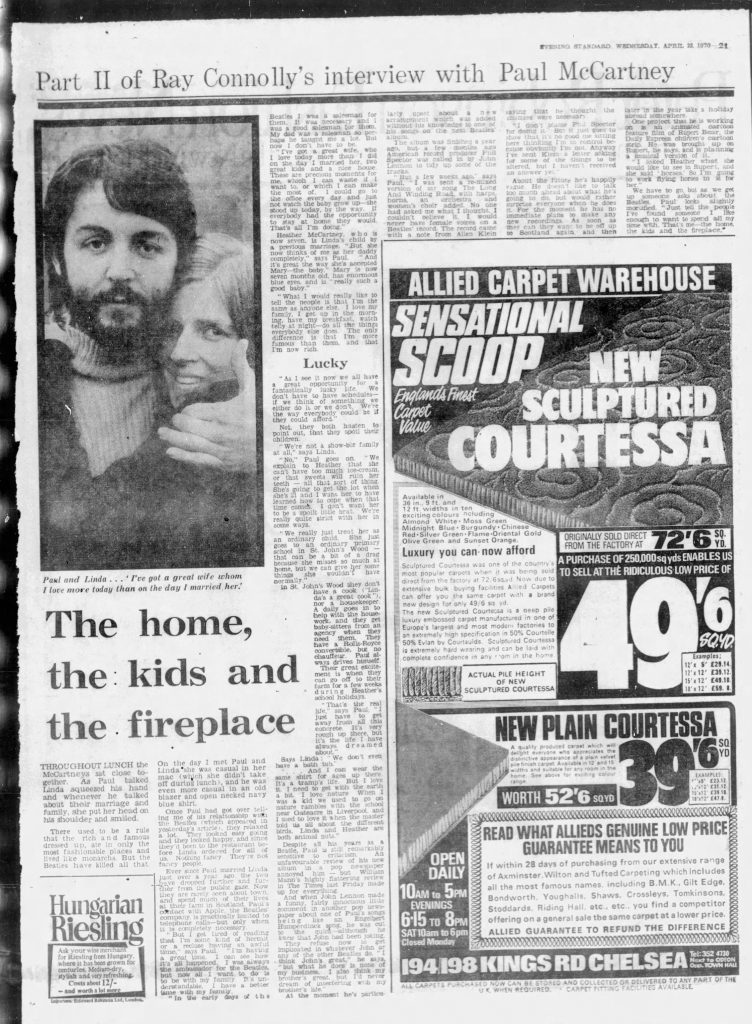

Throughout lunch, the McCartneys sat close together. As Paul talked Linda squeezed his hand and whenever he talked about their marriage and family, she put her head on his shoulder and smiled.

There used to be a rule that the rich and famous dressed up, ate in only the most fashionable places and lived like monarchs. But the Beatles have killed all that. On the day that I met Paul and Linda she was casual in her mac (which she didn’t take off during lunch), and he was even more casual in an old blazer and open-necked navy-blue shirt.

Once Paul had got over telling me of his relationship with the Beatles, they relaxed a lot. They looked easy-going, and since they’d been to the restaurant before, Linda ordered for all of us. Nothing fancy.

Ever since Paul married Linda just over a year ago, the two have dropped further and further from the public gaze. Now they are rarely seen about town, spending much of their lives at their farm in Scotland. Paul’s contact with Apple is virtually limited to telephone calls, and those only when it is completely necessary.

‘But I get tired of reading that I’m some kind of hermit or a recluse having an awful time,’ he says. ‘I’m having a great time. I can see how it’s all happened. I was always the ambassador for the Beatles, but now all I want to do is to be with my family. It’s understandable. I have a better time with my family.

‘In the early days of the Beatles I was a salesman for them. It was necessary and I was a good salesman. My dad was a salesman so perhaps he taught me a lot. But now I don’t have to be.

‘I’ve got a great wife, who I love today more than I did on the day I married her, two great kids and a nice house. These are precious moments for me, which I can waste if I want to, or which I can make the most of. I could go to the office every day and just not watch the baby grow up…she stood up today, by the way. If everybody had the opportunity to stay at home they would. That’s all I’m doing.’

Heather McCartney, who is now seven, is Linda’s child by a previous marriage.

‘But she now thinks of me as her daddy completely,’ Paul says. ‘And it’s great the way she’s accepted Mary, the baby, who is now seven months old. What I would really like to tell the people is that I’m the same as anyone else. I get up in the morning, have my breakfast, watch tele at night…do all the things everybody else does and I love my family. The only difference is that I’m more famous and richer than they are.

‘As I see it now we all have a great opportunity for a fantastically lucky life. We don’t have to have schedules. If we think of something, we either do it or we don’t. We’re the way everybody could be if they could afford it.’

Not, they both hasten to point out, that they spoil their children. ‘We’re not a showbiz family at all,’ says Linda.

‘No,’ Paul goes on. ‘We explain to Heather that she can’t have too much ice-cream, or that sweets ruin her teeth and all that sort of thing. She’s going to get the lot when she’s twenty-one and I want her to have learned how to cope when that time comes. I don’t want her to be a spoilt little brat. We’re really quite strict with her in some ways.

‘We really just treat her as an ordinary child. She goes to an ordinary primary school in St John’s Wood. That can be a bit of a drag because she misses so much at home, but we can give her some things she wouldn’t have normally.’

At home they don’t have a cook (‘Linda’s a great cook’), or a housekeeper. A daily goes in to help with the housework, and they get baby-sitters from an agency when they need them. They have a Rolls-Royce convertible, but no chauffeur. Paul always drives himself.

Their great excitement is when they can go off to their farm in Scotland for a few weeks during Heather’s school holidays.

‘That’s the real life,’ says Paul. ‘I just have to get away from all this concrete. It’s very rough up there, but it’s the life I have always dreamed about.’

‘We don’t even have a bath tub,’ says Linda. ‘… And I can wear the same shirt for ages. It’s a tramp’s life. But I love it. I need to get with the earth a bit. I love nature. When I was a kid we used to go on nature rambles with the school near Gateacre in Liverpool, and I used to love it when the master told us all about the different birds. Linda and Heather are both animal nuts.’

Despite all his years as a Beatle, Paul is still remarkably sensitive to criticism. An unfavourable review of his new album in a pop newspaper annoyed him. And when John made a funny, fairly innocuous little comment in another pop newspaper about one of Paul’s records being like an Engelbert Humperdinck song, he was cut to the quick, although he knew John had been joking. William Mann’s highly flattering review in The Times last Friday, however, made up for everything.

They refuse to get involved in whatever John or any of the other Beatles do. ‘I think John’s great, but what he does is none of my business. I also think my brother’s great, but I’d never dream of interfering with my brother’s life.’

At the moment he’s particularly upset about a new arrangement which was added without his knowledge to one of his songs on the next Beatles’ album, Let It Be. The album was finished last year, but a few months ago American record producer Phil Spector was called in by John Lennon to tidy up some of the tracks.

‘Then a few weeks ago, I was sent a re-mixed version of The Long and Winding Road, with harps, horns, an orchestra and a women’s choir added. No one had asked me what I thought. I couldn’t believe it. I would never have female voices on a Beatles’ record. The record came with a note from Allen Klein saying that he thought the changes were necessary.

‘I don’t blame Phil Spector for doing it. But it just goes to show that it’s no good me sitting here and thinking I’m in control. because obviously I’m not. Anyway, I’ve sent Klein a letter asking for some of the things to be altered, but I haven’t received an answer yet.’

About any plans for the future, Paul is happily vague. He doesn’t like to talk too much about what he’s going to do, but would rather surprise everyone when he does it. For the moment he has no immediate plans to make any new recordings. As soon as he and Linda are able, they want to be off up to Scotland again, and then later in the year to take a holiday abroad.

One project that he is working on is an animated cartoon feature film of Rupert Bear, the Daily Express children’s cartoon strip. He was brought up on Rupert and is planning a musical version of it.

‘I asked Heather what she would like to see in Rupert, and she said “horses”. So I’m going to work flying horses into it for her.’

We have to go, but as we get up someone at another table asks about the Beatles. Paul looks slightly mortified. ‘

Just tell the people I’ve found someone I like enough to want to spend all my time with,’ he replies. ‘That’s me…the home, the kids and the fireplace.’

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.