Saturday, February 24, 1968

Interview for Evening Standard

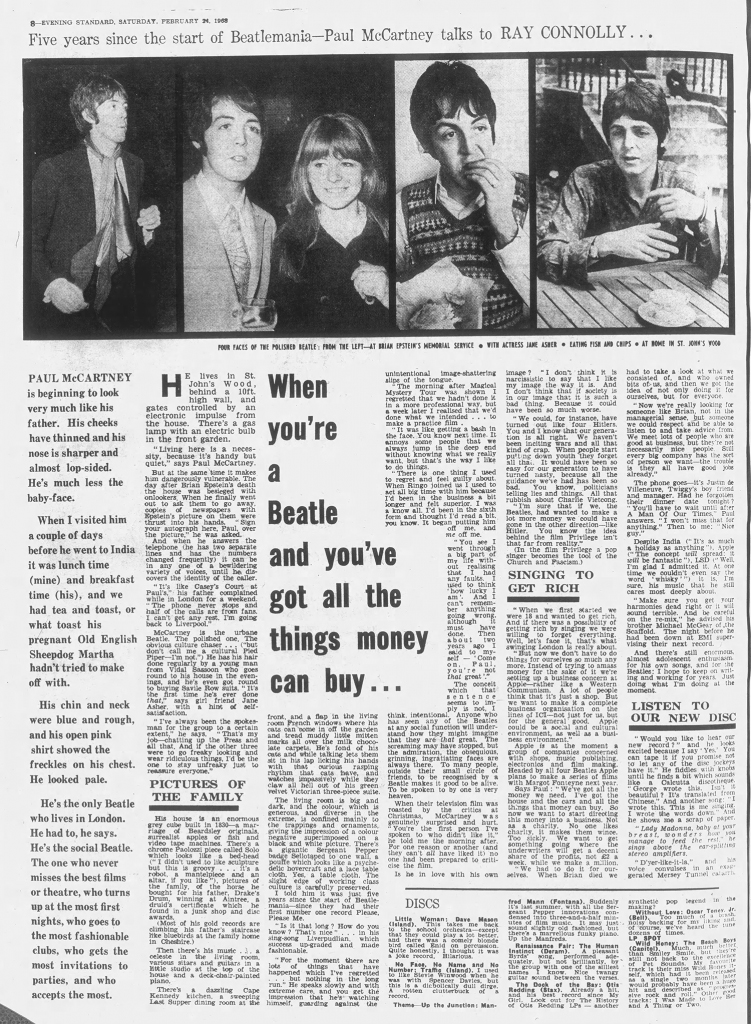

Five years since the start of Beatlemania - Paul McCartney talks to RAY CONNOLLY

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Last updated on April 28, 2022

Saturday, February 24, 1968

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Last updated on April 28, 2022

Previous interview Jan 06, 1968 • Paul McCartney interview for New Musical Express

Article Feb 23, 1968 • The Daily Express publishes psychedelic photos of The Beatles

Article Feb 24, 1968 • The first Apple ad appears in the New Musical Express

Interview Feb 24, 1968 • Paul McCartney interview for Evening Standard

Session Feb 28, 1968 • Recording "Step Inside Love"

Article Feb 29, 1968 • "Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band" wins four Grammy Awards

Next interview Mar 27, 1968 • Interview back from India

This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

Close-up Paul McCartney is much less the baby-face. When I visited him a couple of days before he set off to meditate in India it was lunchtime, mine, and breakfast time, his. His chin and neck were blue and rough, and his open pink shirt showed the freckles on his chest. He looked pale.

He is the only Beatle who lives in London. He has to, he says. He’s the social Beatle. The one who never misses the best films or theatre, the one who turns up at the most first nights, who goes to the most fashionable clubs, who gets the most invitations to parties and who accepts the most.

He lives in St John’s Wood, not far from EMI’s Abbey Road Studios in North London, behind a ten-foot-high wall and gates controlled by an electronic impulse from the house. There is a gas lamp with an electric bulb in the front garden. ‘Living here is a necessity, because it’s handy but quiet,’ he says.

At the same time, it makes him dangerously vulnerable. The day after Brian Epstein’s death the house was besieged with onlookers. When he finally went out to ask them to go away, copies of newspapers with Epstein’s picture on them were thrust into his hands. ‘Sign your autograph here, Paul, over the picture,’ he was told.

And when he answers the telephone (and he has the numbers changed frequently) it can be in any one of a bewildering variety of voices, until he discovers the identity of the caller.

‘It’s like Casey’s Court at Paul’s house,’ his father complained while in London for a weekend. ‘The phone never stops and half of the calls are from fans. I can’t get any rest. I’m going back to Liverpool.’

McCartney is the urbane Beatle: the polished one. The obvious culture chaser … ‘but don’t call me a cultural Pied Piper – because I’m not,’ he insists. He has his hair done regularly by a young man from Vidal Sassoon who goes to his house in the evenings, and he’s even got around to buying Savile Row suits. ‘It’s the first time he’s ever done that,’ says his girlfriend, actress Jane Asher.

‘I’ve always been the spokesman for the group to a certain extent,’ he says. ‘That’s my job…chatting up the Press and all that. If the other three were to go freaky looking and wear ridiculous things, I’d be the one to stay un-freaky just to reassure everyone.’ His house is an enormous grey cube built in 1830, a marriage of Beardsley originals, surrealist apples and fish and video tape machines. There’s a chrome Eduardo Paolozzi piece called Solo which looks like a bed-head (‘I didn’t used to like sculpture, but this is groovy … it’s a robot, a mantelpiece and an altar, if

you like,’) pictures of his family, another of Drake’s Drum, the horse he bought for his father winning a race at Aintree, and a Druid’s certificate which he found in a junk shop. (Most of his gold discs are climbing his father’s staircase like bluebirds at the family home in Heswall, Cheshire.) Then there’s his music … a celeste in the living room, and various sitars and guitars in a little studio at the top of the house, as well as a deck-chair-painted piano.

There’s also a dazzling Cape Kennedy kitchen, and a flap in the living room French windows where his cats can come in off the garden and tread muddy mitten marks over the milk chocolate carpets. He’s fond of his cats, and, while he’s talking, he lets them sit in his lap and lick his hands. Then he watches impassively while they claw all hell out of his green velvet three-piece suite.

The living room is big and dark, and any colour is confined mainly to the trappings and ornaments, giving the impression of a colour negative superimposed on a black and white picture. There’s a gigantic Sergeant Pepper badge sellotaped to one wall and a lace tablecloth. The edge of working class culture is carefully preserved.

Reflecting on the furore after Magical Mystery Tour, I ask if there is anything he’s regretted.

‘For the moment there are lots of things that have happened which I’ve regretted … but nothing in the long run,’ he answers. He speaks slowly and with extreme care, and you get the impression that he’s watching himself, guarding against an unintentional image-shattering slip of the tongue. ‘The morning after Magical Mystery Tour I regretted that we hadn’t done it in a more professional way, but a week later I realised that we’d done what we intended … to make a practice film.

‘It was like getting a bash in the face. You know…next time… (we’ll get it right). It annoys some people that we always jump in the deep end without knowing what we really want, but that’s the way I like to do things.

‘There’s one thing I used to regret and feel guilty about. When Ringo joined us, I used to act all big-time with him… I was a know-all. I’d been in the sixth form and thought I’d read a bit, you know. It began putting him off me, and me off me.

‘You see, I went through a big part of my life without realising that I had any faults. I used to think “how lucky I am”. And I can’t remember going wrong, although I must have done. Then about two years ago I said to myself, “Come on, Paul, you’re not that great”.’

That sentence might seem to imply enormous conceit, but anyone who has seen the Beatles at any social function will understand how they might well imagine that they are indeed that great. The screaming may have stopped, but the admiration, the obsequious, grinning, ingratiating faces are always there. For many people outside their small circle of friends, to be recognised by a Beatle makes it good to be alive.

When Magical Mystery Tour was roasted by the critics Paul was genuinely surprised and hurt. ‘You’re the first person I’ve spoken to who didn’t like it,’ he told me the morning after. For one reason or another, and they can’t all have liked it, no-one had been prepared to criticise the film.

Is he in love with his own image? ‘I don’t think it’s narcissistic to say that I like my image the way it is. And I don’t think that if society is in our image that is such a bad thing. Because it could have been much worse.

‘We could, for instance, have turned out like four Hitlers. You and I know that our generation is all right. We haven’t been inciting wars and all that kind of crap. When people start putting down youth they forget all that. It would have been so easy for our generation to have turned nasty, because all the guidance we’ve had has been so bad. You know, politicians telling lies and things. All that rubbish about Charlie Vietcong.

‘I’m sure that if we, the Beatles, had wanted to make a lot more money we could have gone in the other direction…like Hitler. You know the idea behind the film Privilege isn’t that far from reality.’ In Privilege a pop singer becomes the tool of the Church of Fascism.

‘When we first started we were eighteen and wanted to get rich. And if there was a possibility of getting rich by singing we were willing to forget everything. Well, let’s face it, that’s what swinging London is really about.

‘But now we don’t have to do things for ourselves so much anymore. Instead of trying to amass money for the sake of it we’re setting up a business concern called Apple, which will be rather like a Western Communism. A lot of people think that it’s just a shop. But we want to make it a complete business organisation on the lines of ICI, not just for us, but for the general good. Apple could be a social and cultural environment, as well as a business environment.’ At the moment Apple is a group of companies concerned with shops, music publishing, electronics and film making.

‘We’ve got all the money we need. I’ve got the house and the cars and all the things that money can buy. So now we want to start directing this money into a business. Not as a charity. No one likes charity, it makes them wince. Too sickly. We want to get something going where the underwriters (and staff) will get a decent share of the profits, not two pounds a week, while we make a million.

‘We’ve had to do it for ourselves. When Brian died we had to take a look at what we consisted of, and who owned bits of us, and then we got the idea of not only doing it for ourselves, but for everyone.

‘Now we’re really looking for someone like Brian, not in the managerial sense, but someone we could respect and be able to listen to and take advice from. We meet lots of people who are good at business, but they’re not necessarily nice people. Every big company has the sort of person we want. The trouble is they all have good jobs already.’

Despite the forthcoming trip to India (‘it’s as much a holiday as anything’), Apple (‘the concept will spread: it will be fantastic’), LSD (‘Well, I’m glad I admitted taking it. At one time we couldn’t even say the word “whisky”’) it’s the music that he cares most about. And he still has enormous, almost adolescent enthusiasm for his songs, and for the Beatles: ‘I hope to keep on writing and working for years,’ he says, ‘doing what I’m doing at the moment.’

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.