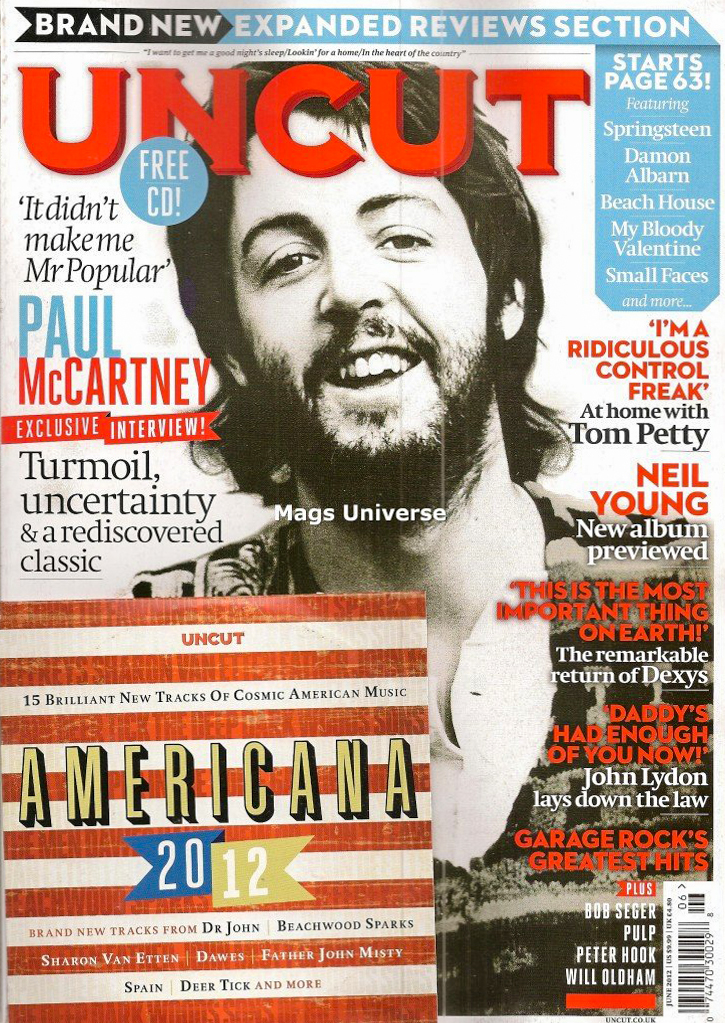

June 2012

Interview for UNCUT

Paul McCartney - Turmoil, uncertainty & a rediscovered classic

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Last updated on September 7, 2025

June 2012

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Last updated on September 7, 2025

Interview May 28, 2012 • Paul McCartney interview for Drowned In Sound

Article May 31, 2012 • Paul McCartney visits The Liverpool Art College

Interview June 2012 • Paul McCartney interview for UNCUT

Article Jun 02, 2012 • Paul McCartney attends Dhani Harrison's wedding

Concert Jun 04, 2012 • The Queen's Diamond Jubilee Concert

Next interview Jun 07, 2012 • Paul McCartney interview for Pitchfork

AlbumThis interview was made to promote the "Ram - Archive Collection" Official album.

This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

HALFWAY THROUGH HIS three-hour concert at Rotterdam’s Ahoy Arena on March 24 — the first date of the second European leg of his On The Run Tour — Paul McCartney took a request from the audience. He plucked out a simple refrain on his ukulele and treated 15,000 fans to “Ram On”, from his 1971 album Ram.

A cheer quickly went up, but it’s likely that the majority of the crowd were unfamiliar with this curio from the post-Beatles and pre-Wings era. It was a time when McCartney, as the fallout of the Fabs reached hysteria pitch, became more infamous than famous.

It’s rare for McCartney to revisit Ram. Despite giving him an American No 1 hit (“Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey”), the album received universally hostile reactions. “I don’t think there’s one tune on it” (Ringo Starr). “Fucking hell, it’s awful” (John Lennon). “The nadir in the decomposition of ’60s rock thus far” (Jon Landau, Rolling Stone). The denunciations were not without agendas. McCartney had successfully sued the other Beatles in the High Court, while critics who craved a return to the gravitas and precision of “Eleanor Rigby” and “Penny Lane” were dismayed to find McCartney writing whimsical songs about life on a Scottish farm — and allowing his wife Linda to sing on them.

For years afterwards, Ram was consigned to a lowly existence in the servants’ quarters of McCartney’s back catalogue. However, its impish giggle and early charm were ultimately persuasive. Ram’s musical sophistication — deceptively simple but with sumptuous orchestrations — is nowadays much-admired. There’s even some love for Linda’s vocals. Reissued this month as part of McCartney’s ongoing Archive Collection series, Ram has been sufficiently rehabilitated for Paul to agree to talk about its origins and context. Interviews with Ram musicians Denny Seiwell (drums) and Dave Spinozza (guitar) were conducted in 2010 during research for a previous Uncut McCartney story.

Is Ram an album you’re fond of?

McCartney: “I have happy memories. A lot of people have said to me over the years, ‘Love Ram, man – love that album.’ So that sent it up in my estimation. These are young people you wouldn’t have expected to notice it.”

It got brutal reviews when it came out, didn’t it?

“Yeah, but there was nothing we could do to satisfy the critics back then. But I thought it was good. We wanted to do something different, strike out in a new direction, and Ram certainly does that.”

It’s very homely: songs about dogs, sheep, “the smell of grass in the meadow” as one lyric puts it.

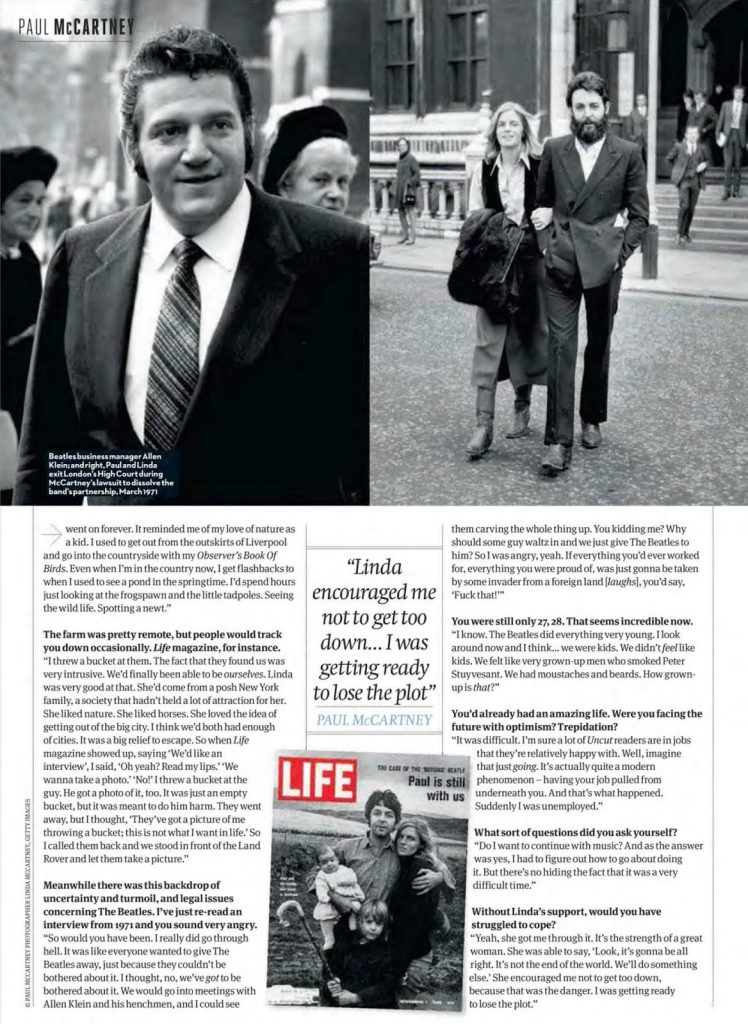

“That’s right. I’d married Linda [in March 1969] and the two of us had escaped the horror of The Beatles’ business by running away to Scotland. There was grass in the meadow. There were babies, there was music, and all of that got reflected. I didn’t have a dog with three legs, I must admit (‘3 Legs’). But I had a ram and I had imaginings.”

You’d bought High Park Farm during the Revolver days, hadn’t you?

“Linda was very instrumental in getting me up there. I’d bought the farm, but was more interested in London – the music scene and all that. She came over from America and said, ‘You’ve got a farm in Scotland? Can we go and see it?’ So we went up there and she said, ‘God, it’s fantastic.’ She was a ruralist. I looked at the farm through her eyes. After the urban heaviness of The Beatles’ negotiations, it was great to have open spaces, fresh air and sky that went on forever. It reminded me of my love of nature as a kid. I used to get out from the outskirts of Liverpool and go into the countryside with my Observer’s Book Of Birds. Even when I’m in the country now, I get flashbacks to when I used to see a pond in the springtime. I’d spend hours just looking at the frogspawn and the little tadpoles. Seeing the wild life. Spotting a newt.”

The farm was pretty remote, but people would track you down occasionally. Life magazine, for instance.

“I threw a bucket at them. The fact that they found us was very intrusive. We’d finally been able to be ourselves. Linda was very good at that. She’d come from a posh New York family, a society that hadn’t held a lot of attraction for her. She liked nature. She liked horses. She loved the idea of getting out of the big city. I think we’d both had enough of cities. It was a big relief to escape. So when Life magazine showed up, saying ‘We’d like an interview’, I said, ‘Oh yeah? Read my lips.’ ‘We wanna take a photo.’ ‘No!’ I threw a bucket at the guy. He got a photo of it, too. It was just an empty bucket, but it was meant to do him harm. They went away, but I thought, ‘They’ve got a picture of me throwing a bucket; this is not what I want in life.’ So I called them back and we stood in front of the Land Rover and let them take a picture.”

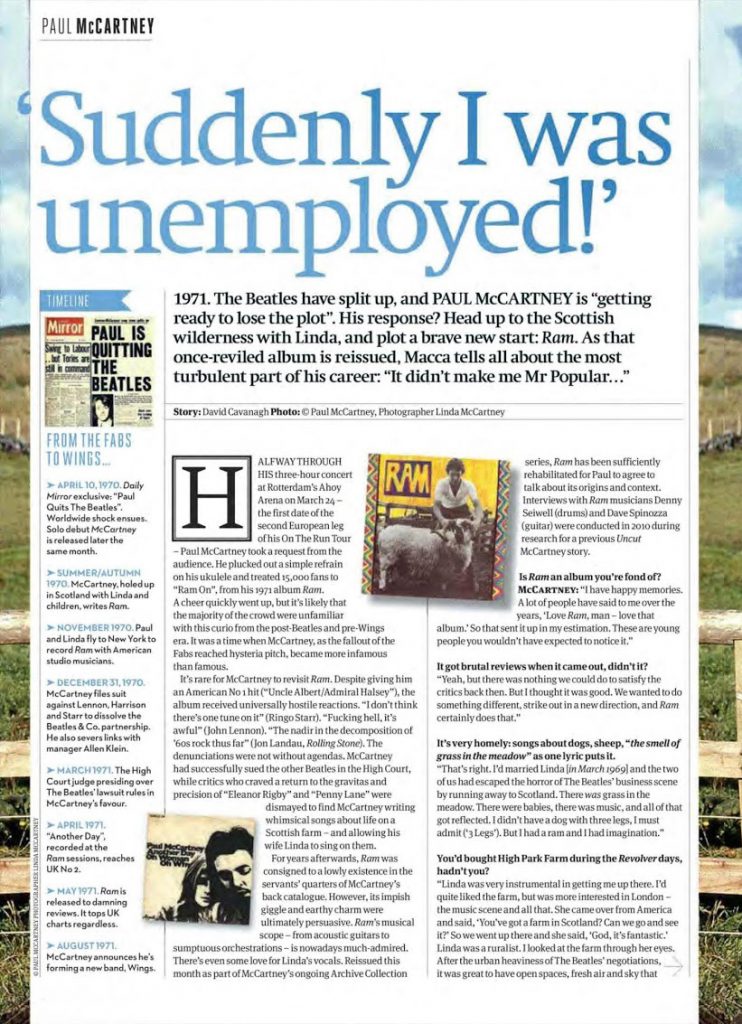

Meanwhile there was this backdrop of uncertainty and turmoil, and legal issues concerning The Beatles. I’ve just re-read an interview from 1971 and you sound very angry.

“So would you have been. I really did go through hell. It was like everyone wanted to give The Beatles away, just because they couldn’t be bothered about it. I thought, no, we’ve got to be bothered about it. We would go into meetings with Allen Klein and his henchmen, and I could see them carving the whole thing up. You kidding me? Why should some guy waltz in and we just give The Beatles to him? So I was angry, yeah. If everything you’d ever worked for, everything you were proud of, was just gonna be taken by some invader from a foreign land [laughs], you’d say, ‘Fuck that!’”

You were still only 27, 28. That seems incredible now.

“I know. The Beatles did everything very young. I look around now and I think… we were kids. We didn’t feel like kids. We felt like very grown-up men who smoked Peter Stuyvesant. We had moustaches and beards. How grown-up is that?”

You’d already had an amazing life. Were you facing the future with optimism? Trepidation?

“It was difficult. I’m sure a lot of Uncut readers are in jobs that they’re relatively happy with. Well, imagine that just going. It’s actually quite a modern phenomenon – having your job pulled from underneath you. And that’s what happened. Suddenly I was unemployed.”

What sort of questions did you ask yourself?

“Do I want to continue with music? And as the answer was yes, I had to figure out how to go about doing it. But there’s no hiding the fact that it was a very difficult time.”

Without Linda’s support, would you have struggled to cope?

“Yeah, she got me through it. It’s the strength of a great woman. She was able to say, ‘Look, it’s gonna be all right. It’s not the end of the world. We’ll do something else.’ She encouraged me not to get too down, because that was the danger. I was getting ready to lose the plot.”

Why is Ram credited to both of you?

“It was a co-effort. On a few songs, we actually sat down and worked them out together. I would sit in the kitchen, plonking away, and she’d sing something and I’d write it down. But the most important thing was her support at the time. It was our album. It was our chance to do our own thing.”

Ram is so rural and Scottish in places; it’s funny to think that it was recorded in expensive studios in Midtown Manhattan.

“Yes, a lot of it was. And then we did some recording in LA. But I wrote most of it in Scotland, so the imprint of it was our Scottish idyll. I went to New York to try and find musicians to play with, and found a few cool guys. Denny Seiwell. Dave Spinozza. Hugh McCracken.”

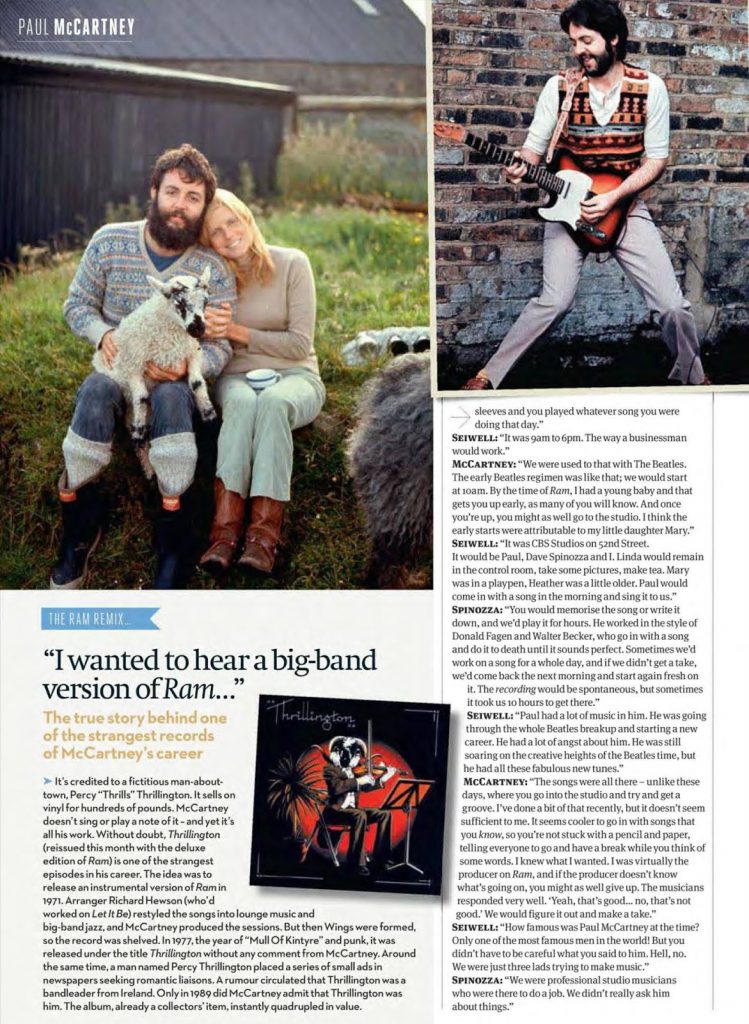

DENNY SEIWELL: “He’d always wanted to make a record in New York – you know, the grass is always greener. The English guys all thought the American studios were better. He came to town and held auditions for drummers. They were fairly clandestine arrangements. I had no idea I was about to meet Paul McCartney.”

DAVE SPINOZZA: “Paul called the Musicians’ Union in New York and asked them to suggest guitar players. I’d liked some of The Beatles’ records but I wasn’t a groupie or anything like that.”

SEIWELL: “I turned up and there was Paul, sitting in the basement of a ratty old building on 43rd Street with Linda and a beautiful set of drums from Studio Instrument Rentals. I said, ‘Hey, you’re Paul McCartney!’ He said, ‘That’s right.’ He said he’d like to hear me play some rock’n’roll, so I sat down and started slamming away. That’s how I got the gig for Ram.”

SPINOZZA: “The sessions for Ram would begin early in the morning. It surprised me how regimented they were. Paul and Linda would arrive together with the kids, and you drank your cup of coffee and you rolled up your sleeves and you played whatever song you were doing that day.”

SEIWELL: “It was 9am to 6pm. The way a businessman would work.”

MCCARTNEY: “We were used to that with The Beatles. The early Beatles regimen was like that; we would start at 10am. By the time of Ram, I had a young baby and that gets you up early, as many of you will know. And once you’re up, you might as well go to the studio. I think the early starts were attributable to my little daughter Mary.”

SEIWELL: “It was CBS Studios on 52nd Street. It would be Paul, Dave Spinozza and I. Linda would remain in the control room, take some pictures, make tea. Mary was in a playpen, Heather was a little older. Paul would come in with a song in the morning and sing it to us.”

SPINOZZA: “You would memorise the song or write it down, and we’d play it for hours. He worked in the style of Donald Fagen and Walter Becker, who go into a song and do it to death until it sounds perfect. Sometimes we’d work on a song for a whole day, and if we didn’t get a take, we’d come back the next morning and start again fresh on it. The recording would be spontaneous, but sometimes it took us 10 hours to get there.”

SEIWELL: “Paul had a lot of music in him. He was going through the whole Beatles breakup and starting a new career. He had a lot of angst about him. He was still soaring on the creative heights of the Beatles time, but he had all these fabulous new tunes.”

MCCARTNEY: “The songs were all there – unlike these days, where you go into the studio and try and get a groove. I’ve done a bit of that recently, but it doesn’t seem sufficient to me. It seems cooler to go in with songs that you know, so you’re not stuck with a pencil and paper, telling everyone to go and have a break while you think of some words. I knew what I wanted. I was virtually the producer on Ram, and if the producer doesn’t know what’s going on, you might as well give up. The musicians responded very well. ‘Yeah, that’s good… no, that’s not good.’ We would figure it out and make a take.”

SEIWELL: “How famous was Paul McCartney at the time? Only one of the most famous men in the world! But you didn’t have to be careful what you said to him. Hell, no. We were just three lads trying to make music.”

SPINOZZA: “We were professional studio musicians who were there to do a job. We didn’t really ask him about things.”

SEIWELL: “I sensed that he didn’t want to talk about The Beatles. It wasn’t a taboo subject, but no-one brought it up. Did he ever mention John Lennon? No, never.”

The other three Beatles all played on each other’s records in the early ’70s. Did you deliberately want to avoid that?

MCCARTNEY: “No, I got close to it a few times. But you see, I got blamed for The Beatles breaking up, which wasn’t actually true. It was John who left The Beatles [in September 1969], but I carried the can for it. And because I was trying to save Apple, I was talking to lawyers and I said, ‘Look, I just want to sue Allen Klein.’ And they said, ‘Well, he’s not a party to the agreements.’ I said, ‘Well, who is?’ They said, ‘The other Beatles.’ So I thought, ‘Oh my God.’ You know, the mouth of the tunnel had suddenly slammed shut. I was stuck. Klein was going to take it all. So I had a few nightmare months before I decided that if the only way to save Apple was to sue the other Beatles, then that’s what I had to do. But it didn’t make me Mr Popular. Not with them, and not with the fans.

“It was a long time before people got the hang of it. And it took a long time before any of the other guys said, ‘Thanks.’ They did eventually. It was like [hurriedly], ‘Thanks.’ ‘For what?’ ‘Oh… [muttering] for saving Apple.’ You know, guys don’t thank each other easily. Our guys didn’t anyway.”

So that’s the context of Ram. Is that why you had a little poke at John and Yoko in “Too Many People”?

“Yeah, ‘Too many people preaching practises’. It was just a minor poke. That’s all it was. I think that some other pokes were imagined. ‘Too many people preaching practises’. That was it, really. It was like, don’t let them tell you what to do.”

The other theory is that you wrote “Dear Boy” as a criticism of John for leaving Cynthia for Yoko.

“No, it was nothing to do with him leaving Cynthia. Funnily enough, that song was about Linda’s first husband. I thought Linda was great, and it was like… ‘I guess you never knew, dear boy’ – that was all it was. That’s what I’m seeing. That is absolutely the note that was written. And if you check it out, it works. It wasn’t written about John.”

How important did the Ram sessions feel at the time?

SPINOZZA: “I’ve played with a lot of singer-songwriters in my career. But working on that record, it was obvious that Paul was seriously creative. He was witty and funny, but when it was time to play, it was time to play. They weren’t rock’n’roll sessions; he was very serious about his music. At the end of recording, he had a little party for us, very low-key. We had some wine and he told a few jokes, but that was it. It wasn’t a hang.”

SEIWELL: “We did 23 songs in six weeks. He overdubbed the strings at Phil Ramone’s place, A&R Studios. Then I got a call from Paul to go out to California, where we did ‘Dear Boy’ and a couple more tracks. Some of the material was experimental. Some of it was done for a Rupert The Bear album that he was making. Some of it was used later [eg ‘Little Lamb Dragonfly’ and ‘Get On The Right Thing’ on 1973’s Red Rose Speedway].”

SPINOZZA: “He was a genius. Everything he sang and played, was just so musical. Every idea, every suggestion… He was really meticulous about capturing the song. He could have made [Ram] anywhere as far as I’m concerned. He could have made it in England. He could have made it in Germany. When you listen to his records, there’s a certain McCartney stamp – a certain way that he hears – and that’s what he always goes for. That’s what makes him him.”

SEIWELL: “I got on with my life and went back to doing sessions. Then, after the record was released, Paul called out of the blue and said, ‘How about coming over to Scotland for a little vacation?’ ‘Sounds good to me.’ When I got there, he said, ‘I really miss being in a band. Let’s put one together.’ That’s when we formed Wings.”

MCCARTNEY: “‘How do you ‘do’ a band?’ was the question. You could do the supergroup thing, or you could return to your roots – and that’s what I wanted to do. I wanted to experience being at the bottom again. I wanted to get a camaraderie, a chemistry together.”

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.