July 2004

Interview for UNCUT

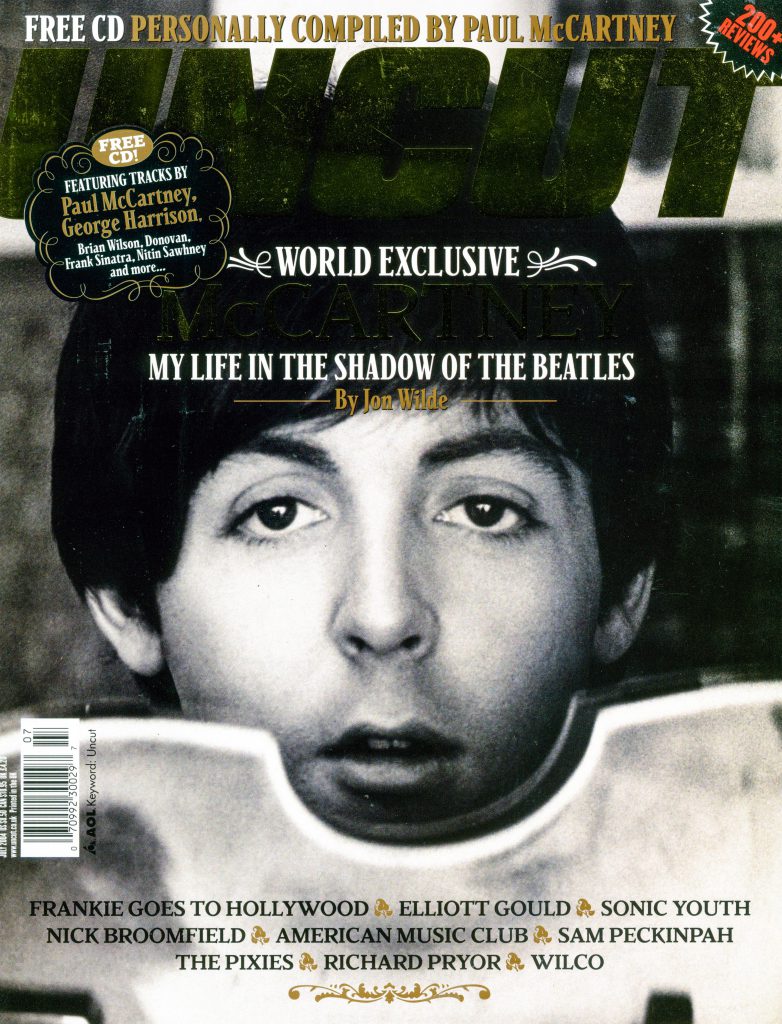

My Life In The Shadow Of The Beatles

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Last updated on September 3, 2023

July 2004

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Last updated on September 3, 2023

Previous interview Jun 11, 2004 • Paul McCartney interview for The Guardian

Concert Jun 24, 2004 • France • Paris

Concert Jun 26, 2004 • Glastonbury festival

Interview July 2004 • Paul McCartney interview for UNCUT

Interview July 2004 • Paul McCartney interview for MOJO

Interview Jul 03, 2004 • Paul McCartney interview for The Guardian

Officially appears on Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (UK Mono)

Officially appears on Unplugged (The Official Bootleg)

Unreleased song

Officially appears on Revolver (UK Mono)

Officially appears on From Me To You / Thank You Girl

Officially appears on Revolver (UK Mono)

Officially appears on The Beatles (Mono)

Officially appears on Tug Of War

Officially appears on Revolver (UK Mono)

Officially appears on I Want To Hold Your Hand / This Boy

Officially appears on Yesterday and Today (Mono)

Officially appears on Live And Let Die / I Lie Around

Officially appears on Love Me Do / P.S. I Love You

Officially appears on Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (UK Mono)

Officially appears on Mary Had A Little Lamb / Little Woman Love (UK)

Officially appears on Mull Of Kintyre / Girls’ School

Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)

Officially appears on Rubber Soul (UK Mono)

Officially appears on Paperback Writer / Rain (UK)

Officially appears on Strawberry Fields Forever / Penny Lane

Officially appears on Please Please Me / Ask Me Why

Officially appears on The Beatles (Mono)

Officially appears on The Ballad Of John And Yoko / Old Brown Shoe (UK - 1969)

Officially appears on Ram

Officially appears on Choba B CCCP

Why Don't We Do It In The Road?

Officially appears on The Beatles (Mono)

Officially appears on Help! (Mono)

This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

TOMORROW NEVER KNOWS. So you thought John was the arty, druggy, weird one… In this world exclusive, PAUL MCCARTNEY talks candidly about surviving the ’60s, his relationship with Lennon, and finally being ordained as the cool Beatle.

LOS ANGELES. SPRING 2004. A recording studio on Sunset Boulevard. Uncut waits for Sir Paul McCartney to arrive and the nerve-ends are taut like a stretched bow. With good reason. We’ve been flown five-and-a-half thousand miles for an exclusive audience with the world-famous Beatle but there’s no telling what to expect. McCartney’s willing to talk but no one’s saying for how long, no one’s saying what subjects are off-limits. “Just see how it goes,” his PR has advised. “Get him talking, keep him interested, who knows?” The nerve-ends tighten further when we remind ourselves exactly who we’re about to meet. Not just any common or garden rock star, but one very significant quarter of the band widely regarded as the greatest and most influential there’s ever been. McCartney. One of the few living pop luminaries on whom the sobriquet “Legend” is not wasted.

AFTER A SHORT WAIT, HE STROLLS IN, casually dapper, munching his way through a Hobnob. He greets Uncut with an affable wink and a matey grin, offers up a tin of biscuits, oozes a supernatural sense of normality.

“You’ve come all the way from Brighton?” he says, politely puzzled. “I’ve got a house down there. We could have done this in the pub across the road over a plate of chips.”

McCartney has spent more than 40 years attempting to master the difficult art of being Paul McCartney. On the evidence, he appears to have honed it to near-perfection, outwardly manifesting both bloke-next-door, thumbs-aloft approachability and commanding don’t-mess-with-me-I-used-to- be-in-The-Beatles authority. Over the course of three days and three lengthy interviews, he demonstrates far more of the former than the latter. Although, early on, he’ll gently let you know where he draws the line, tacitly suggesting that, so long as those conversational parameters are respected, he’ll be happy to talk and talk and talk.

It’s a good time to be talking to McCartney. The years of creative underachievement are long behind him. Once again, he’s making records that are both critically lauded and commercially successful. No longer is the name McCartney a byword for MOR. At 62, he’s considered unstoppably cool again.

Unstoppable he is. After years off the road, he’s back touring with a vengeance, breaking records wherever he goes: playing to more than two million people in 2002-2003, including a career-best audience of 500,000 in Rome, now limbering up to play to 700,000 at 13 shows on a European tour that will climax with his first ever appearance at the Glastonbury Festival.

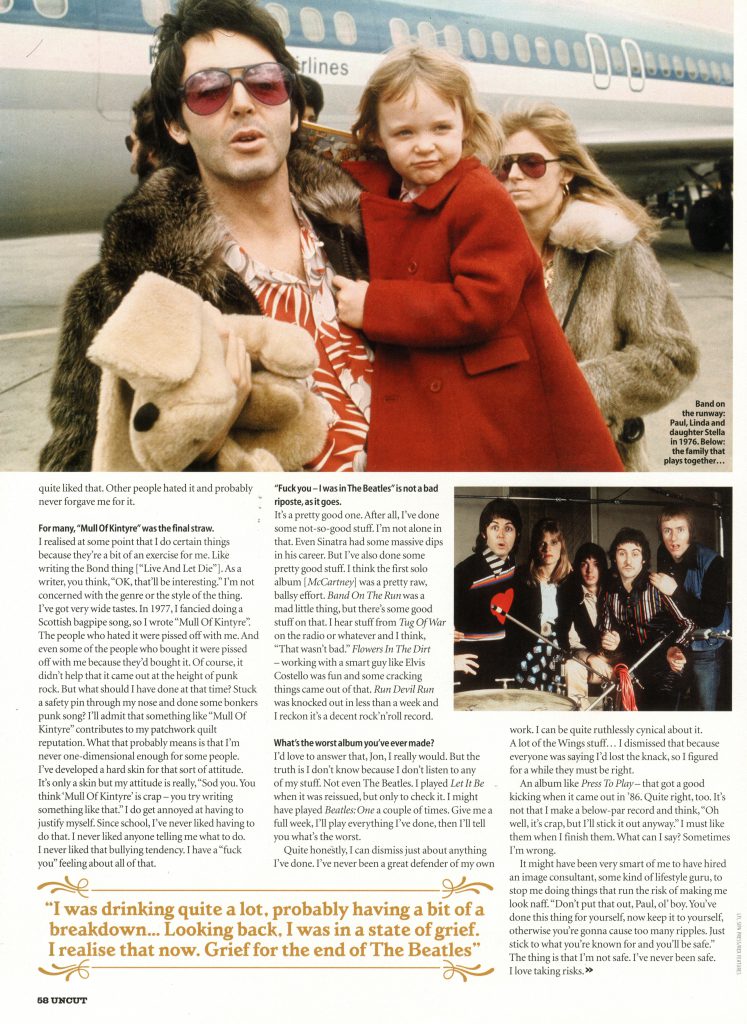

On a personal level, his life couldn’t be in much better shape. The emotional turmoil that followed Linda’s death has been superseded by what he describes as “a new-found bliss” with marriage to Heather Mills and the birth of a daughter, Beatrice Lilly.

No wonder he appears to be in such fine fettle as he tells Uncut to switch on the tape recorder and fire away. We’re only too happy to oblige.

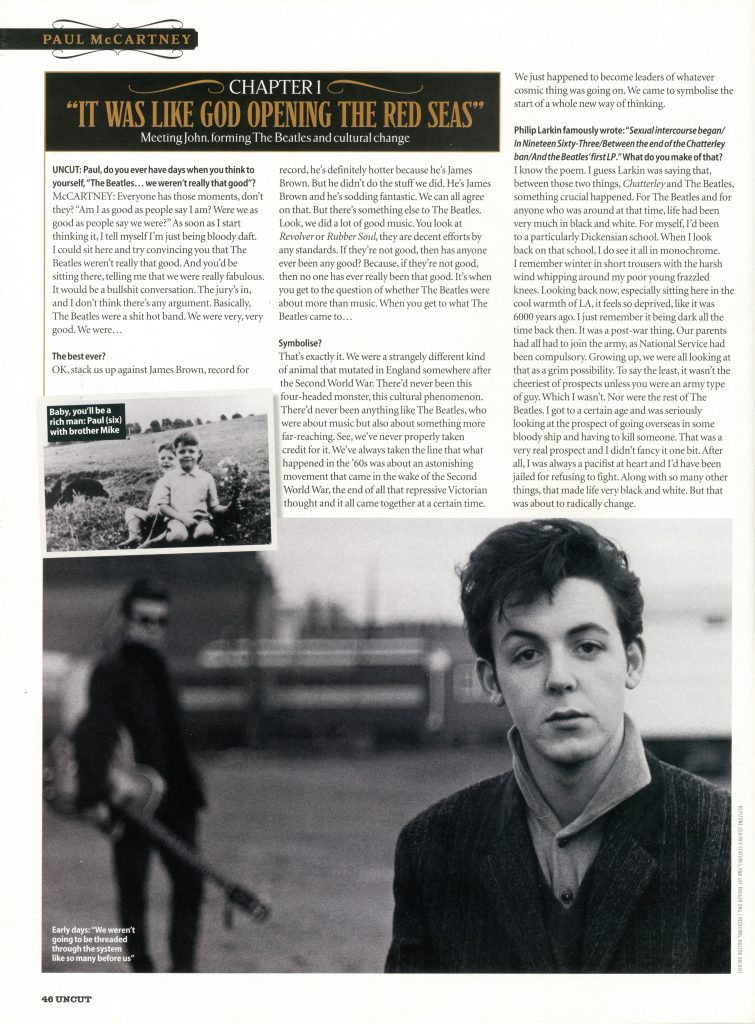

UNCUT: Paul, do you ever have days when you think to yourself, “The Beatles… we weren’t really that good”?

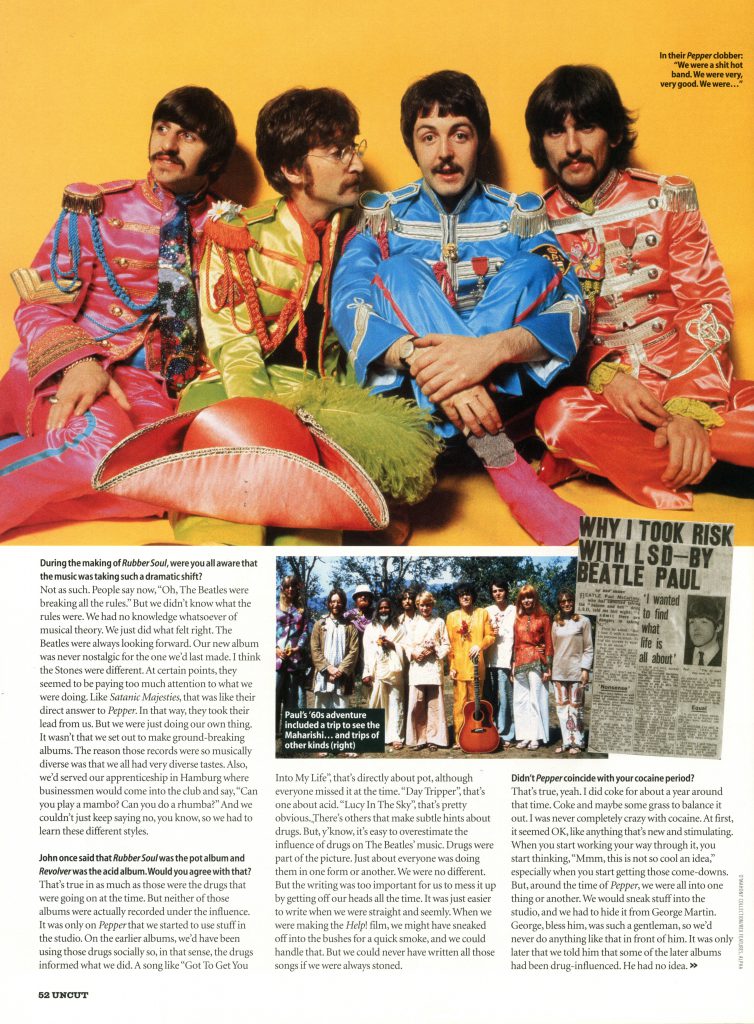

MCCARTNEY: Everyone has those moments, don’t they? “Am I as good as people say I am? Were we as good as people say we were?” As soon as I start thinking it, I tell myself I’m just being bloody daft. I could sit here and try convincing you that The Beatles weren’t really that good. And you’d be sitting there, telling me that we were really fabulous. It would be a bullshit conversation. The jury’s in, and I don’t think there’s any argument. Basically, The Beatles were a shit hot band. We were very, very good. We were…

The best ever?

OK, stack us up against James Brown, record for record, he’s definitely hotter because he’s James Brown. But he didn’t do the stuff we did. He’s James Brown and he’s sodding fantastic. We can all agree on that. But there’s something else to The Beatles. Look, we did a lot of good music. You look at Revolver or Rubber Soul, they are decent efforts by any standards. If they’re not good, then has anyone ever been any good? Because, if they’re not good, then no one has ever really been that good. It’s when you get to the question of whether The Beatles were about more than music. When you get to what The Beatles came to…

Symbolise?

That’s exactly it. We were a strangely different kind of animal that mutated in England somewhere after the Second World War. There’d never been this four-headed monster, this cultural phenomenon. There’d never been anything like The Beatles, who were about music but also about something more far-reaching. See, we’ve never properly taken credit for it. We’ve always taken the line that what happened in the ’60s was about an astonishing movement that came in the wake of the Second World War, the end of all that repressive Victorian thought and it all came together at a certain time.

We just happened to become leaders of whatever cosmic thing was going on. We came to symbolise the start of a whole new way of thinking.

Philip Larkin famously wrote: “Sexual intercourse began/ In Nineteen Sixty-Three/Between the end of the Chatterley ban/And the Beatles’ first LP.”What do you make of that?

I know the poem. I guess Larkin was saying that, between those two things, Chatterley and The Beatles, something crucial happened. For The Beatles and for anyone who was around at that time, life had been very much in black and white. For myself, I’d been to a particularly Dickensian school. When I look back on that school, I do see it all in monochrome. I remember winter in short trousers with the harsh wind whipping around my poor young frazzled knees. Looking back now, especially sitting here in the cool warmth of LA, it feels so deprived, like it was 6000 years ago. I just remember it being dark all the time back then. It was a post-war thing. Our parents had all had to join the army, as National Service had been compulsory. Growing up, we were all looking at that as a grim possibility. To say the least, it wasn’t the cheeriest of prospects unless you were an army type of guy. Which I wasn’t. Nor were the rest of The Beatles. I got to a certain age and was seriously looking at the prospect of going overseas in some bloody ship and having to kill someone. That was a very real prospect and I didn’t fancy it one bit. After all, I was always a pacifist at heart and I’d have been jailed for refusing to fight. Along with so many other things, that made life very black and white. But that was about to radically change.

What was the turning point for you?

The end of National Service. Not just for me. For anyone of a certain age. Without that, there could have been no Beatles. To me, that was like God opening the Red Sea for Moses and the Israelites to come pouring through. It was like God decreed there would be no National Service. Well, that was extremely handy. Nice one, mate. That certainly changes things. It meant that we were the first generation for so many years that didn’t have that we’ll-make-a-man-of-you threat hanging over them. We weren’t going to be threaded through the system like so many before us.

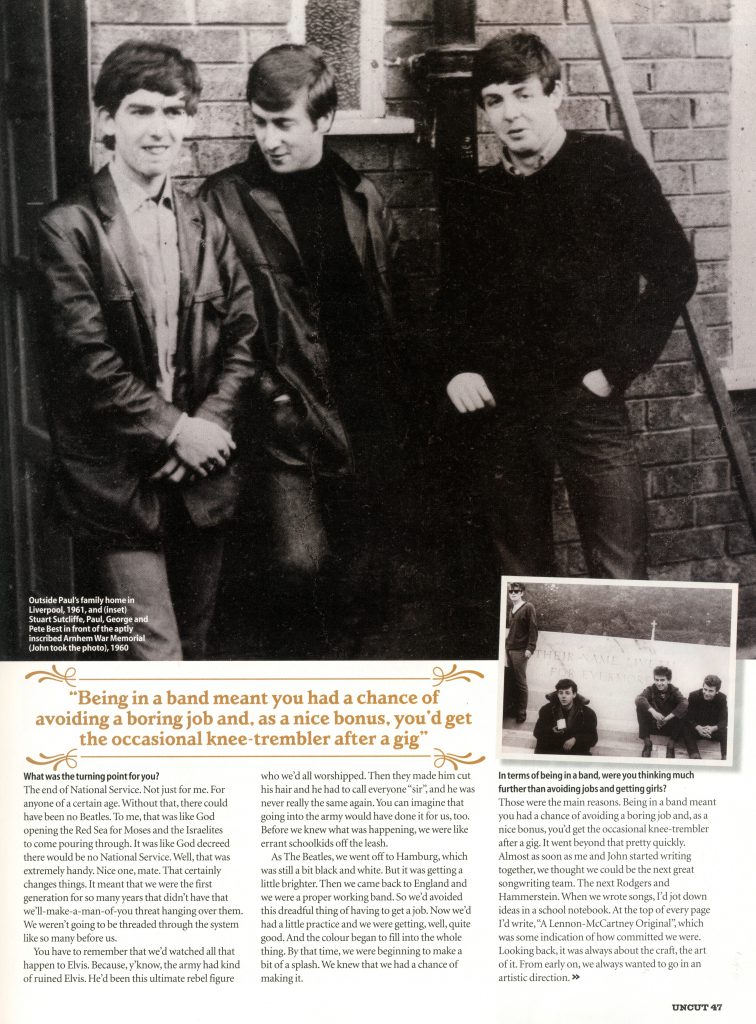

You have to remember that we’d watched all that happen to Elvis. Because, y’know, the army had kind of ruined Elvis. He’d been this ultimate rebel figure who we’d all worshipped. Then they made him cut his hair and he had to call everyone “sir”, and he was never really the same again. You can imagine that going into the army would have done it for us, too. Before we knew what was happening, we were like errant schoolkids off the leash.

As The Beatles, we went off to Hamburg, which was still a bit black and white. But it was getting a little brighter. Then we came back to England and we were a proper working band. So we’d avoided this dreadful thing of having to get a job. Now we’d had a little practice and we were getting, well, quite good. And the colour began to fill into the whole thing. By that time, we were beginning to make a bit of a splash. We knew that we had a chance of making it.

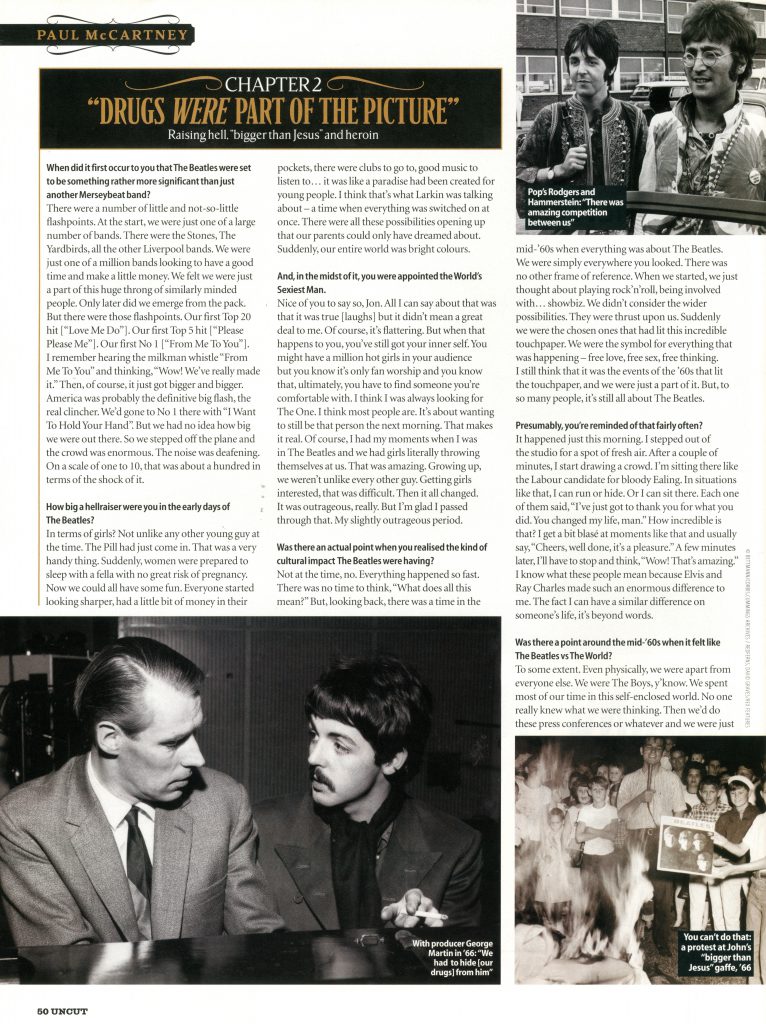

In terms of being in a band, were you thinking much further than avoiding jobs and getting girls?

Those were the main reasons. Being in a band meant you had a chance of avoiding a boring job and, as a nice bonus, you’d get the occasional knee-trembler after a gig. It went beyond that pretty quickly. Almost as soon as me and John started writing together, we thought we could be the next great songwriting team. The next Rodgers and Hammerstein. When we wrote songs, I’d jot down ideas in a school notebook. At the top of every page, I’d write, “A Lennon-McCartney Original”, which was some indication of how committed we were. Looking back, it was always about the craft, the art of it. From early on, we always wanted to go in an artistic direction.

Writing songs seemed to come easy to you and John.

Not so much easily as quickly. It was out of necessity as much as anything. We’d sag off school and write songs at my house. We’d start at two in the afternoon and we had to be finished by five so we could clean up and clear out before my dad got home. We wrote loads of stuff. We’d stuff some Twinings Tea in a pipe, smoke that and write songs. It wasn’t all good. But we always came up with something. In all the years I wrote with John, I can’t remember a single occasion when we didn’t come up with a song. At worst, we’d write at least one every day. It all happened at an amazing pace. Because it had to. When we came to record the first Beatles album [Please Please Me], we did it in a single day because that’s all the time there was. That’s how things were done in those days. The studio was booked for one day. We went in at 10 in the morning, played our live set all the way through, then we went home. The following day, we had two gigs to do. There was no time for messing about. It’s great when you do it like that. It’s quite magical, really. You just grab hold of stuff. Your driver says, “Have I been busy? I’ve been working eight days a week, mate.” And you think, “Hello, that sounds like a song title.” So you write it, filling in from the title.

Did you see The Beatles differently from John Lennon?

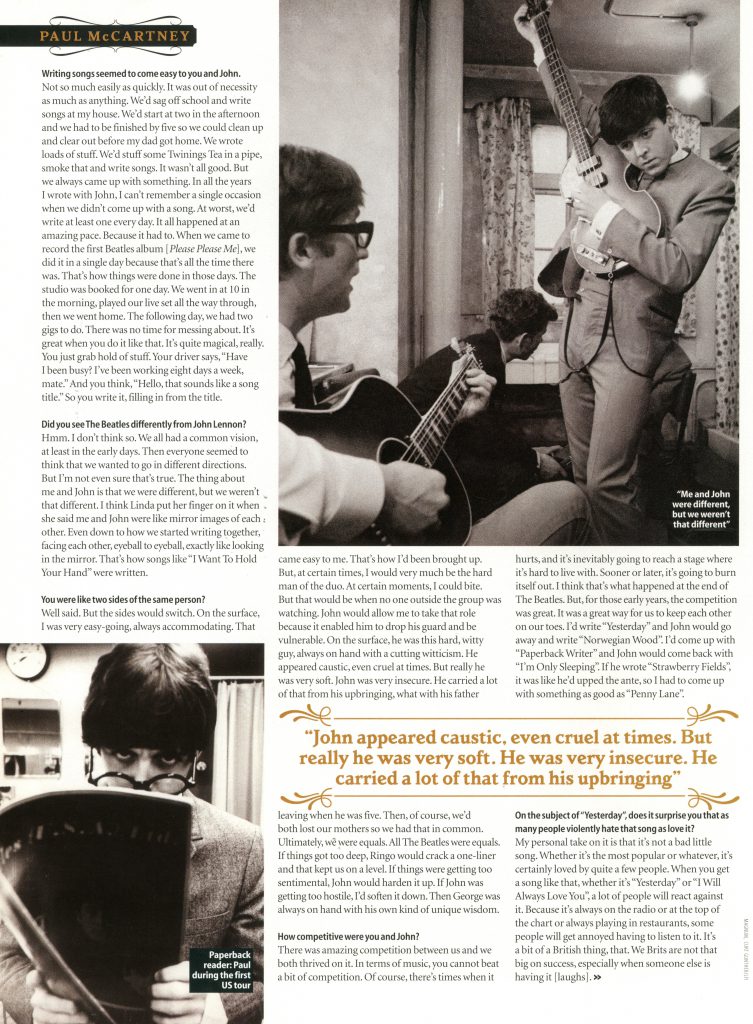

Hmm. I don’t think so. We all had a common vision. at least in the early days. Then everyone seemed to think that we wanted to go in different directions. But I’m not even sure that’s true. The thing about me and John is that we were different, but we weren’t that different. I think Linda put her finger on it when she said me and John were like mirror images of each other. Even down to how we started writing together, facing each other, eyeball to eyeball, exactly like looking in the mirror. That’s how songs like “I Want To Hold Your Hand” were written.

You were like two sides of the same person?

Well said. But the sides would switch. On the surface, I was very easy-going, always accommodating. That came easy to me. That’s how I’d been brought up. But, at certain times, I would very much be the hard man of the duo. At certain moments, I could bite.

But that would be when no one outside the group was watching, John would allow me to take that role because it enabled him to drop his guard and be vulnerable. On the surface, he was this hard, witty guy, always on hand with a cutting witticism. He appeared caustic, even cruel at times. But really he was very soft. John was very insecure. He carried a lot of that from his upbringing, what with his father leaving when he was five. Then, of course, we’d both lost our mothers so we had that in common. Ultimately, we were equals. All The Beatles were equals. If things got too deep, Ringo would crack a one-liner and that kept us on a level. If things were getting too sentimental, John would harden it up. If John was getting too hostile, I’d soften it down. Then George was always on hand with his own kind of unique wisdom.

How competitive were you and John?

There was amazing competition between us and we both thrived on it. In terms of music, you cannot beat a bit of competition. Of course, there’s times when it hurts, and it’s inevitably going to reach a stage where it’s hard to live with. Sooner or later, it’s going to burn itself out. I think that’s what happened at the end of The Beatles. But, for those early years, the competition was great. It was a great way for us to keep each other on our toes. I’d write “Yesterday” and John would go away and write “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)”. I’d come up with “Paperback Writer” and John would come back with “I’m Only Sleeping”. If he wrote “Strawberry Fields”, it was like he’d upped the ante, so I had to come up with something as good as “Penny Lane”.

On the subject of “Yesterday”, does it surprise you that as many people violently hate that song as love it?

My personal take on it is that it’s not a bad little song. Whether it’s the most popular or whatever, it’s certainly loved by quite a few people. When you get a song like that, whether it’s “Yesterday” or “I Will Always Love You”, a lot of people will react against it. Because it’s always on the radio or at the top of the chart or always playing in restaurants, some people will get annoyed having to listen to it. It’s a bit of a British thing, that. We Brits are not that big on success, especially when someone else is having it [laughs].

When did it first occur to you that The Beatles were set to be something rather more significant than just another Merseybeat band?

There were a number of little and not-so-little flashpoints. At the start, we were just one of a large number of bands. There were the Stones. The Yardbirds, all the other Liverpool bands. We were just one of a million bands looking to have a good time and make a little money. We felt we were just a part of this huge throng of similarly-minded people. Only later did we emerge from the pack. But there were those flashpoints. Our first Top 20 hit “Love Me Do”. Our first Top 5 hit “Please Please Me”. Our first No 1 [“From Me To You”]. I remember hearing the milkman whistle “From Me To You” and thinking, “Wow! We’ve really made it.” Then, of course, it just got bigger and bigger. America was probably the definitive big flash, the real clincher. We’d gone to No 1 there with “I Want To Hold Your Hand”. But we had no idea how big we were out there. So we stepped off the plane and the crowd was enormous. The noise was deafening. On a scale of one to 10, that was about a hundred in terms of the shock of it.

How big a hellraiser were you in the early days of The Beatles?

In terms of girls? Not unlike any other young guy at the time. The Pill had just come in. That was a very handy thing. Suddenly, women were prepared to sleep with a fella with no great risk of pregnancy. Now we could all have some fun. Everyone started looking sharper, had a little bit of money in their pockets, there were clubs to go to, good music to listen to… it was like a paradise had been created for young people. I think that’s what Larkin was talking about a time when everything was switched on at once. There were all these possibilities opening up that our parents could only have dreamed about. Suddenly, our entire world was bright colours.

And, in the midst of it, you were appointed the World’s Sexiest Man.

Nice of you to say so, Jon. All I can say about that was that it was true [laughs] but it didn’t mean a great deal to me. Of course, it’s flattering, But when that happens to you, you’ve still got your inner self. You might have a million hot girls in your audience but you know it’s only fan worship and you know that, ultimately, you have to find someone you’re comfortable with. I think I was always looking for The One. I think most people are. It’s about wanting to still be that person the next morning. That makes it real. Of course, I had my moments when I was in The Beatles and we had girls literally throwing themselves at us. That was amazing. Growing up, we weren’t unlike every other guy. Getting girls interested, that was difficult. Then it all changed. It was outrageous, really. But I’m glad I passed through that. My slightly outrageous period.

Was there an actual point when you realised the kind of cultural impact The Beatles were having?

Not at the time, no. Everything happened so fast. There was no time to think, “What does all this mean?” But, looking back, there was a time in the mid-’60s when everything was about The Beatles. We were simply everywhere you looked. There was no other frame of reference. When we started, we just thought about playing rock’n’roll, being involved with… showbiz. We didn’t consider the wider possibilities. They were thrust upon us. Suddenly we were the chosen ones who had lit this incredible touchpaper. We were the symbol for everything that was happening – free love, free sex, free-thinking. I still think that it was the events of the ’60s that lit the touchpaper, and we were just a part of it. But, to so many people, it’s still all about The Beatles.

Presumably, you’re reminded of that fairly often?

It happened just this morning. I stepped out of the studio for a spot of fresh air. After a couple of minutes, I start drawing a crowd. I’m sitting there like the Labour candidate for bloody Ealing. In situations like that, I can run or hide. Or I can sit there. Each one of them said, “I’ve just got to thank you for what you did. You changed my life, man.” How incredible is that? I get a bit blasé at moments like that and usually say, “Cheers, well done, it’s a pleasure.” A few minutes later, I’ll have to stop and think, “Wow! That’s amazing.” I know what these people mean because Elvis and Ray Charles made such an enormous difference to me. The fact I can have a similar difference on someone’s life, it’s beyond words.

Was there a point around the mid-’60s when it felt like The Beatles vs The World?

To some extent. Even physically, we were apart from everyone else. We were The Boys, y’know. We spent most of our time in this self-enclosed world. No one really knew what we were thinking. Then we’d do these press conferences or whatever and we were just four Liverpool lads taking the piss. It was very funny at first. They’d ask the most ridiculous questions and we’d come straight back at them. Like they’d ask what we thought about Beethoven and Ringo would say, “Well, I like his poems.” Or they’d ask how we found America. And one of us would say, “We turned left at the traffic lights.” What do we do when we’re in our hotel rooms?”We ice skate.” They’d ask us if “Eleanor Rigby” was about lesbians and we’d say, “Of course it is.”They’d say, “Why is that?” And we’d say, “Because all four of us are lesbians.” It was just a bit more interesting than saying it’s a song about a lonely old spinster. We just loved taking the piss out of daft questions.

Then John just happened to mention that The Beatles were bigger than Jesus.

Well, that’s when the laughing stopped. That’s when it got serious. Of course, John never meant to say that The Beatles were literally bigger than Christ. He was only referring to the lack of attendance in church. He was actually taking a sympathetic point of view.

Was he wrong to publicly apologise for it?

Yeah, that’s easy to say. But you weren’t there, mate. We were in the American South just after the story had broken. I still remember this young blond boy, no more than 12 years old, banging on the window, raging, like we were devils. When you come up against that, oh dear me, you think, “Who needs this?” We had religious fanatics burning our records, the KKK were making death threats. There was a whole climate of hate and fear and we were bang in the middle of it. Of course, you look back and feel glad that those people were against you, because we were certainly against them.

MAD APPLE AND MAGIC ALEX – McCartney on The Beatle’ ill-advised business venture

ADVISED BY THEIR ACCOUNTANTS that setting up their own business would save them £3m in tax, The Beatles set up Apple Corps in the spring of 1967. But this would be no ordinary business, Apple would be a record label, a chain of boutiques, a school and a magazine. Unfortunately, these ambitious enterprises would largely be run by a motley crew of thieves, compulsive hashish smokers, George Harrison’s Hell’s Angel friends and any late-’60s freak who happened to be passing by the office. Then John Lennon’s “personal guru”, a part-time TV repair man called Magic Alex (Alexis Mardas), started coming up with expensive ideas for levitating houses, coloured air, even a Beatles flying saucer… The money flowed out like the Ganges at full spate. After two years of this nonsense, The Beatles found themselves perilously close to bankruptcy.

McCARTNEY: I can see people will read about Apple now and think it a proper hoot, a right old laugh. Well, I can tell you, I wasn’t laughing l at the time. It was a heavy time for all of us, and the Apple fiasco just piled on the agony.

It would be fair to say that we were open to suggestions at that time. Possibly due to illegal stimulants. John had arrived with Magic Alex and introduced him as the new guru. I don’t think the rest of us believed in any of that. He was simply John’s mate. The thing about Magic Alex is that he had some interesting ideas. He just couldn’t pull them off. We didn’t know anything about physics or engineering. So, when this guy starts talking about how he’s invented musical wallpaper-“loudpaper, I think it was going to be called-we sort of went along with it.”Yeah, mate, why not? Off you go, here’s a load of money.”

Coloured air, that was one of the ones that was a bit too far out. The levitating house I only heard about later. John and George might have agreed to donate the engines from their cars to help build this bloody flying saucer. But certainly didn’t go that far. Maybe I was a bit more sceptical than the others. Anyway, Magic Alex couldn’t actually do any of this stuff. He said he’d build us a state-of-the-art recording studio and we let him get on with it, but he didn’t have a bloody clue where to start.

You know that scene in The Rutles where the George character is being interviewed outside the Apple building and, behind him, there’s all these shifty characters making off with TV sets and expensive tables? Well, that’s what it was like. It was a case of anything that wasn’t nailed down. It was a complete free-for-all. There was no one there to say, “Hang about, we’re not having any of this far-out nonsense. Stopnicking the fucking stereos, lads. “At one point, we found out that one of the office boys was making off with the lead from the roof. People would walk into the boutique, just grab stuff off the shelves and walk out. It was total chaos. There was always a wild party going on. I remember showing someone round the office late one night and there was a couple having it off on the floor. Looking back, it was always heading for a fall.

That went on for some time, and then came this strange moment when we learnt we were broke.

That was hard to believe. We’d made a few successful records. How could we have run out of money? It was insane. It wouldn’t have been so bad if we’d spent the money ourselves. Apple was a big learning curve for me. I learnt that, if you’re going to be connected with anything like a business, it’s got to have accountants and people who watch what happens. And it’s probably not a good idea to get in a load of Hell’s Angels to do the job.

During the making of Rubber Soul, were you all aware that the music was taking such a dramatic shift?

Not as such. People say now, “Oh, The Beatles were breaking all the rules.” But we didn’t know what the rules were. We had no knowledge whatsoever of musical theory. We just did what felt right. The Beatles were always looking forward. Our new album was never nostalgic for the one we’d last made. I think the Stones were different. At certain points, they seemed to be paying too much attention to what we were doing. Like Satanic Majesties, that was like their direct answer to Pepper. In that way, they took their lead from us. But we were just doing our own thing. It wasn’t that we set out to make ground-breaking albums. The reason those records were so musically diverse was that we all had very diverse tastes. Also, we’d served our apprenticeship in Hamburg where businessmen would come into the club and say, “Can you play a mambo? Can you do a rhumba?” And we couldn’t just keep saying no, you know, so we had to learn these different styles.

John once said that Rubber Soul was the pot album and Revolver was the acid album. Would you agree with that?

That’s true in as much as those were the drugs that were going on at the time. But neither of those albums were actually recorded under the influence. It was only on Pepper that we started to use stuff in the studio. On the earlier albums, we’d have been using those drugs socially so, in that sense, the drugs informed what we did. A song like “Got To Get You Into My Life”, that’s directly about pot, although everyone missed it at the time. “Day Tripper”, that’s one about acid. “Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds”, that’s pretty obvious. There’s others that make subtle hints about drugs. But, y’know, it’s easy to overestimate the influence of drugs on The Beatles’ music. Drugs were part of the picture. Just about everyone was doing them in one form or another. We were no different. But the writing was too important for us to mess it up by getting off our heads all the time. It was just easier to write when we were straight and seemly. When we were making the Help! film, we might have sneaked off into the bushes for a quick smoke, and we could handle that. But we could never have written all those songs if we were always stoned.

Didn’t Pepper coincide with your cocaine period?

That’s true, yeah. I did coke for about a year around that time. Coke and maybe some grass to balance it out. I was never completely crazy with cocaine. At first, it seemed OK, like anything that’s new and stimulating. When you start working your way through it, you start thinking, “Mmm, this is not so cool an idea,” especially when you start getting those come-downs. But, around the time of Pepper, we were all into one thing or another. We would sneak stuff into the studio, and we had to hide it from George Martin. George, bless him, was such a gentleman, so we’d never do anything like that in front of him. It was only later that we told him that some of the later albums had been drug-influenced. He had no idea.

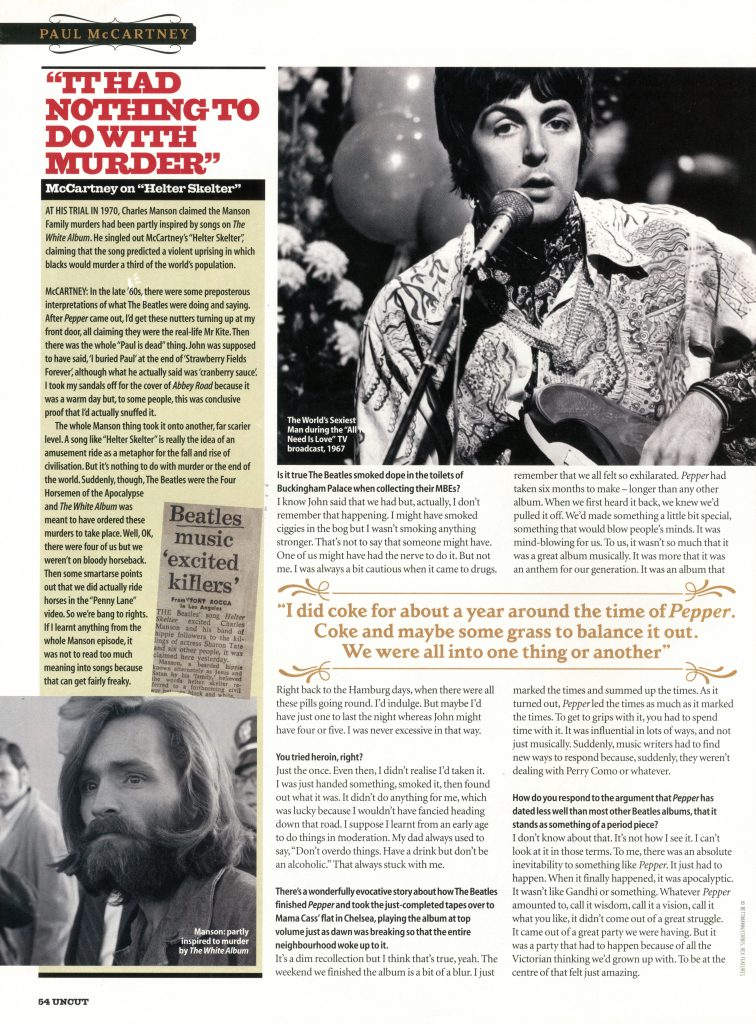

“IT HAD NOTHING TO DO WITH MURDER” – McCartney On “Helter Skelter”

AT HIS TRIAL IN 1970, Charles Manson claimed the Manson Family murders had been partly inspired by songs on The White Album. He singled out McCartney’s “Helter Skelter”, claiming that the song predicted a violent uprising in which blacks would murder a third of the world’s population.

MCCARTNEY: In the late ’60s, there were some preposterous interpretations of what The Beatles were doing and saying. After Pepper came out, I’d get these nutters turning up at my front door, all claiming they were the real-life Mr Kite. Then there was the whole “Paul is dead” thing. John was supposed to have said, I buried Paul at the end of ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, although what he actually said was ‘cranberry sauce’ I took my sandals off for the cover of Abbey Road because it was a warm day but, to some people, this was conclusive proof that I’d actually snuffed it.

The whole Manson thing took it onto another, far scarier level. A song like “Helter Skelter” is really the idea of an amusement ride as a metaphor for the fall and rise of civilisation. But it’s nothing to do with murder or the end of the world. Suddenly, though, The Beatles were the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and The White Album was meant to have ordered these murders to take place. Well, OK, there were four of us but we weren’t on bloody horseback. Then some smartarse points out that we did actually ride horses in the “Penny Lane ” video. So we’re bang to rights. If I learnt anything from the whole Manson episode, it was not to read too much meaning into songs because that can get fairly freaky.

Is it true The Beatles smoked dope in the toilets of Buckingham Palace when collecting their MBEs?

I know John said that we had but, actually, I don’t remember that happening, I might have smoked ciggies in the bog but I wasn’t smoking anything stronger. That’s not to say that someone might have. One of us might have had the nerve to do it. But not me. I was always a bit cautious when it came to drugs.

Right back to the Hamburg days, when there were all these pills going round. I’d indulge. But maybe I’d have just one to last the night whereas John might have four or five. I was never excessive in that way.

You tried heroin, right?

Just the once. Even then, I didn’t realise I’d taken it. I was just handed something, smoked it, then found out what it was. It didn’t do anything for me, which was lucky because I wouldn’t have fancied heading down that road. I suppose I learnt from an early age to do things in moderation. My dad always used to say, “Don’t overdo things. Have a drink but don’t be an alcoholic.” That always stuck with me.

There’s a wonderfully evocative story about how The Beatles finished Pepper and took the just-completed tapes over to Mama Cass’ flat in Chelsea, playing the album at top volume just as dawn was breaking so that the entire neighbourhood woke up to it.

It’s a dim recollection but I think that’s true, yeah. The weekend we finished the album is a bit of a blur. I just remember that we all felt so exhilarated. Pepper had taken six months to make – longer than any other album. When we first heard it back, we knew we’d pulled it off. We’d made something a little bit special, something that would blow people’s minds. It was mind-blowing for us. To us, it wasn’t so much that it was a great album musically. It was more that it was an anthem for our generation. It was an album that marked the times and summed up the times. As it turned out, Pepper led the times as much as it marked the times. To get to grips with it, you had to spend time with it. It was influential in lots of ways, and not just musically. Suddenly, music writers had to find new ways to respond because, suddenly, they weren’t dealing with Perry Como or whatever.

How do you respond to the argument that Pepper has dated less well than most other Beatles albums, that it stands as something of a period piece?

I don’t know about that. It’s not how I see it. I can’t look at it in those terms. To me, there was an absolute inevitability to something like Pepper. It just had to happen. When it finally happened, it was apocalyptic. It wasn’t like Gandhi or something. Whatever Pepper amounted to, call it wisdom, call it a vision, call it what you like, it didn’t come out of a great struggle. It came out of a great party we were having. But it was a party that had to happen because of all the Victorian thinking we’d grown up with. To be at the centre of that felt just amazing.

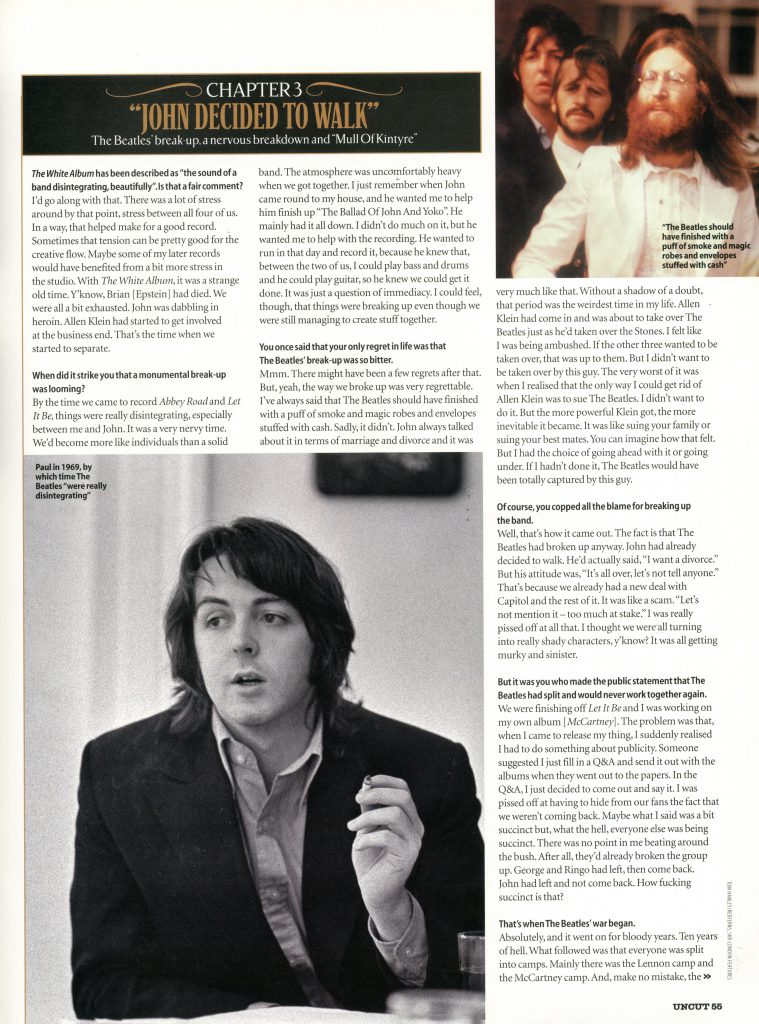

The White Album has been described as “the sound of a band disintegrating, beautifully”. Is that a fair comment?

I’d go along with that. There was a lot of stress around by that point, stress between all four of us. In a way, that helped make for a good record. Sometimes that tension can be pretty good for the creative flow. Maybe some of my later records would have benefited from a bit more stress in the studio. With The White Album, it was a strange old time. Y’know, Brian Epstein had died. We were all a bit exhausted. John was dabbling in heroin. Allen Klein had started to get involved at the business end. That’s the time when we started to separate.

When did it strike you that a monumental break-up was looming?

By the time we came to record Abbey Road and Let It Be, things were really disintegrating, especially between me and John. It was a very nervy time. We’d become more like individuals than a solid band. The atmosphere was uncomfortably heavy when we got together. I just remember when John came round to my house, and he wanted me to help him finish up “The Ballad Of John And Yoko” He mainly had it all down. I didn’t do much on it, but he wanted me to help with the recording. He wanted to run in that day and record it, because he knew that, between the two of us, I could play bass and drums and he could play guitar, so he knew we could get it done. It was just a question of immediacy. I could feel, though, that things were breaking up even though we were still managing to create stuff together.

You once said that your only regret in life was that The Beatles break-up was so bitter.

Mmm. There might have been a few regrets after that. But, yeah, the way we broke up was very regrettable. I’ve always said that The Beatles should have finished with a puff of smoke and magic robes and envelopes stuffed with cash. Sadly, it didn’t. John always talked about it in terms of marriage and divorce and it was very much like that. Without a shadow of a doubt, that period was the weirdest time in my life. Allen Klein had come in and was about to take over The Beatles just as he’d taken over the Stones. I felt like I was being ambushed. If the other three wanted to be taken over, that was up to them. But I didn’t want to be taken over by this guy. The very worst of it was when I realised that the only way I could get rid of Allen Klein was to sue The Beatles. I didn’t want to do it. But the more powerful Klein got, the more inevitable it became. It was like suing your family or suing your best mates. You can imagine how that felt. But I had the choice of going ahead with it or going under. If I hadn’t done it, The Beatles would have been totally captured by this guy.

Of course, you copped all the blame for breaking up the band.

Well, that’s how it came out. The fact is that The Beatles had broken up anyway. John had already decided to walk. He’d actually said. “I want a divorce.” But his attitude was, “It’s all over, let’s not tell anyone.” That’s because we already had a new deal with Capitol and the rest of it. It was like a scam. “Let’s not mention it – too much at stake.” I was really pissed off at all that. I thought we were all turning into really shady characters, y’know? It was all getting murky and sinister.

But it was you who made the public statement that The Beatles had split and would never work together again.

We were finishing off Let It Be and I was working on my own album [McCartney). The problem was that, when I came to release my thing, I suddenly realised I had to do something about publicity. Someone suggested I just fill in a Q&A and send it out with the albums when they went out to the papers. In the Q&A, I just decided to come out and say it. I was pissed off at having to hide from our fans the fact that we weren’t coming back. Maybe what I said was a bit succinct but, what the hell, everyone else was being succinct. There was no point in me beating around the bush. After all, they’d already broken the group up. George and Ringo had left, then come back. John had left and not come back. How fucking succinct is that?

That’s when The Beatles’ war began.

Absolutely, and it went on for bloody years. Ten years of hell. What followed was that everyone was split into camps. Mainly there was the Lennon camp and the McCartney camp. And, make no mistake, the other three had the upper hand. There were three of them and one of me. John, George and Ringo had been my best mates. Now they were my enemies. That was really, really hard to take.

Interestingly, the war of words between yourself and John was largely fought out in songs, culminating in John’s scathing, merciless “How Do You Sleep?”

Well, we weren’t speaking at all by that time. So the only way we could communicate our feelings was through writing songs.

Wouldn’t it have been easier to have simply picked the phone up and had a right old go at each other?

Well, yeah [laughs]. That might have been a bit more sensible. As it was, the whole thing just escalated nastily. I’d taken a few mild digs at John in some of my early solo songs like “Too Many People” (from Ram]. I was trying to tell John something with that. I wasn’t really addressing the world. Then he came out with “How Do You Sleep?” where he suggested that the only thing I ever did was “Yesterday” and so on. John later said that the song was about himself. Well, it didn’t sound like that. What can I say? John was pure gold. He was great, a fabulous guy and a beautiful person but he didn’t have the monopoly on common sense. Basically, he was as daft as the next man.

Would it be fair to say that you experienced something of a nervous breakdown in the early ’70s?

Something like that. In The Beatles, we’d always had this running joke: “What are we going to do when the bubble bursts?” Then it did burst and I went up to my farm in Scotland, wondering what the hell I was going to do next. I seriously thought about giving up music altogether. I was thinking, “Maybe I should become a nuclear physicist or something.” It was a bloody hard time. It was difficult to get up in the morning. I was drinking quite a lot. Probably having a bit of a nervous breakdown, like you say. Looking back, I was in a state of grief. I realise that now. Grief for the end of The Beatles. The only way I could get out of that was get back to recording, then going out on the road. And all that led eventually to the formation of Wings.

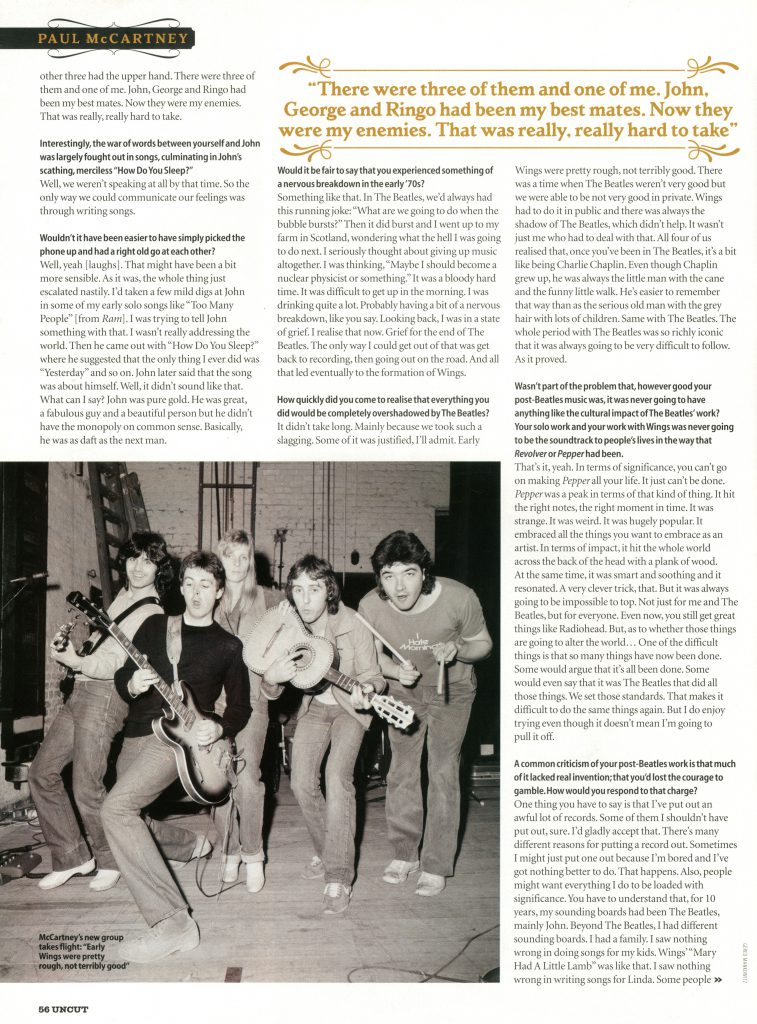

How quickly did you come to realise that everything you did would be completely overshadowed by The Beatles?

It didn’t take long. Mainly because we took such a slagging. Some of it was justified, I’ll admit. Early Wings were pretty rough, not terribly good. There was a time when The Beatles weren’t very good but we were able to be not very good in private. Wings had to do it in public and there was always the shadow of The Beatles, which didn’t help. It wasn’t just me who had to deal with that. All four of us realised that, once you’ve been in The Beatles, it’s a bit like being Charlie Chaplin. Even though Chaplin grew up, he was always the little man with the cane and the funny little walk. He’s easier to remember that way than as the serious old man with the grey hair with lots of children. Same with The Beatles. The whole period with The Beatles was so richly iconic that it was always going to be very difficult to follow. As it proved.

Wasn’t part of the problem that, however good your post-Beatles music was, it was never going to have anything like the cultural impact of The Beatles’ work? Your solo work and your work with Wings was never going to be the soundtrack to people’s lives in the way that Revolver or Pepper had been.

That’s it, yeah. In terms of significance, you can’t go on making Pepper all your life. It just can’t be done. Pepper was a peak in terms of that kind of thing. It hit the right notes, the right moment in time. It was strange. It was weird. It was hugely popular. It embraced all the things you want to embrace as an artist. In terms of impact, it hit the whole world across the back of the head with a plank of wood. At the same time, it was smart and soothing and it resonated. A very clever trick, that. But it was always going to be impossible to top. Not just for me and The Beatles, but for everyone. Even now, you still get great things like Radiohead. But, as to whether those things are going to alter the world… One of the difficult things is that so many things have now been done. Some would argue that it’s all been done. Some would even say that it was The Beatles that did all those things. We set those standards. That makes it difficult to do the same things again. But I do enjoy trying even though it doesn’t mean I’m going to pull it off.

A common criticism of your post-Beatles work is that much of it lacked real invention; that you’d lost the courage to gamble. How would you respond to that charge?

One thing you have to say is that I’ve put out an awful lot of records. Some of them I shouldn’t have put out, sure. I’d gladly accept that. There’s many different reasons for putting a record out. Sometimes I might just put one out because I’m bored and I’ve got nothing better to do. That happens. Also, people might want everything I do to be loaded with significance. You have to understand that, for 10 years, my sounding boards had been The Beatles, mainly John. Beyond The Beatles, I had different sounding boards. I had a family. I saw nothing wrong in doing songs for my kids. Wings’ “Mary Had A Little Lamb” was like that. I saw nothing wrong in writing songs for Linda. Some people quite liked that. Other people hated it and probably never forgave me for it.

For many, “Mull Of Kintyre” was the final straw.

I realised at some point that I do certain things because they’re a bit of an exercise for me. Like writing the Bond thing [“Live And Let Die”]. As a writer, you think, “OK, that’ll be interesting.” I’m not concerned with the genre or the style of the thing. I’ve got very wide tastes. In 1977, I fancied doing a Scottish bagpipe song, so I wrote “Mull Of Kintyre”. The people who hated it were pissed off with me. And even some of the people who bought it were pissed off with me because they’d bought it. Of course, it didn’t help that it came out at the height of punk rock. But what should I have done at that time?! Stuck a safety pin through my nose and done some bonkers, punk song? I’ll admit that something like “Mull Of Kintyre” contributes to my patchwork quilt reputation. What that probably means is that I’m never one-dimensional enough for some people. I’ve developed a hard skin for that sort of attitude. It’s only a skin but my attitude is really, “Sod you. You think Mull Of Kintyre’ is crap-you try writing something like that.” I do get annoyed at having to justify myself. Since school, I’ve never liked having to do that. I never liked anyone telling me what to do. I never liked that bullying tendency. I have a “fuck you” feeling about all of that.

“Fuck you – I was in The Beatles” is not a bad riposte, as it goes.

It’s a pretty good one. After all, I’ve done some not-so-good stuff. I’m not alone in that. Even Sinatra had some massive dips in his career. But I’ve also done some pretty good stuff. I think the first solo album [McCartney] was a pretty raw, ballsy effort. Band On The Run was a mad little thing, but there’s some good stuff on that. I hear stuff from Tug Of War on the radio or whatever and I think, “That wasn’t bad.” Flowers In The Dirt – working with a smart guy like Elvis Costello was fun and some cracking things came out of that. Run Devil Run was knocked out in less than a week and I reckon it’s a decent rock’n’roll record.

What’s the worst album you’ve ever made?

I’d love to answer that, Jon, I really would. But the truth is I don’t know because I don’t listen to any of my stuff. Not even The Beatles. I played Let It Be when it was reissued, but only to check it. I might have played ‘Beatles: One’ a couple of times. Give me a full week, I’ll play everything I’ve done, then I’ll tell you what’s the worst.

Quite honestly, I can dismiss just about anything I’ve done. I’ve never been a great defender of my own work. I can be quite ruthlessly cynical about it. A lot of the Wings stuff… I dismissed that because everyone was saying I’d lost the knack, so I figured for a while they must be right.

An album like Press To Play – that got a good kicking when it came out in ’86. Quite right, too. It’s not that I make a below-par record and think “Oh well, it’s crap, but I’ll stick it out anyway.” I must like them when I finish them. What can I say? Sometimes I’m wrong.

It might have been very smart of me to have hired an image consultant, some kind of lifestyle guru, to stop me doing things that run the risk of making me look naff. “Don’t put that out, Paul, of boy. You’ve done this thing for yourself, now keep it to yourself, otherwise you’re gonna cause too many ripples. Just stick to what you’re known for and you’ll be safe.” The thing is that I’m not safe. I’ve never been safe. I love taking risks.

Going back to The Beatles… the revisionism that came in the wake of John’s death seemed to irk you. Was that essentially a concern for how posterity would view you?

There was a time when the idea of posterity was important for all of us. I remember being shocked one day when John started worrying how people would remember him when he was gone. It was an incredibly vulnerable thing for him to come out with. I said to him then, “They’ll remember you as a fucking genius because that’s what you are. But you won’t give a shit because you’ll be up there flying across the universe.” Then I got to a point where I could see what John meant and maybe I started worrying too much about how my part in it was going to be remembered. There was that time after John’s death where it really got out of hand. It was like, “John was the only real talent in the band and Paul booked the studios and stuff.” I started to think I ought to speak up because, well, this was my own history that was being written up. But it goes on. I keep dipping into that Revolution In The Head book.

Written, of course, by the late, great pop scholar and Uncut contributor lan MacDonald. A hugely compelling read by any yardstick.

Well, it might be compelling reading for you. But not for me it isn’t. Because I keep finding all the mistakes in it. “McCartney did this because of that…” And I’m sitting there thinking, “No, I didn’t.” Or, “John Lennon was out of his head on this when he wrote that.” No, he wasn’t. I should know because I was fucking there. It’s all this received wisdom shit. It’s good that someone like lan bothered to write a book about us. I’m sure a lot of it is very perceptive. But what do you do when you’re me? When someone is telling you what it’s like to be in a room writing “A Day In The Life” and you’re thinking, “No, that’s not what it was like at all.” It can be very enraging, that sort of thing.

But surely you can’t spend the rest of your life correcting what you perceive to be inaccuracies.

I’ve actually stopped trying now. It got to a point where I realised that I couldn’t go on trying to correct the things that were wrong. Because I wasn’t doing myself any favours. Maybe it was starting to look like I was dancing on John’s grave. A lot of people felt I was trying to take more credit than was due, like I was trying to put John down. But John would have been happy to have acknowledged my part in it all. He was never one to grab credit that wasn’t due to him.

So is posterity less important to you now than it used to be?

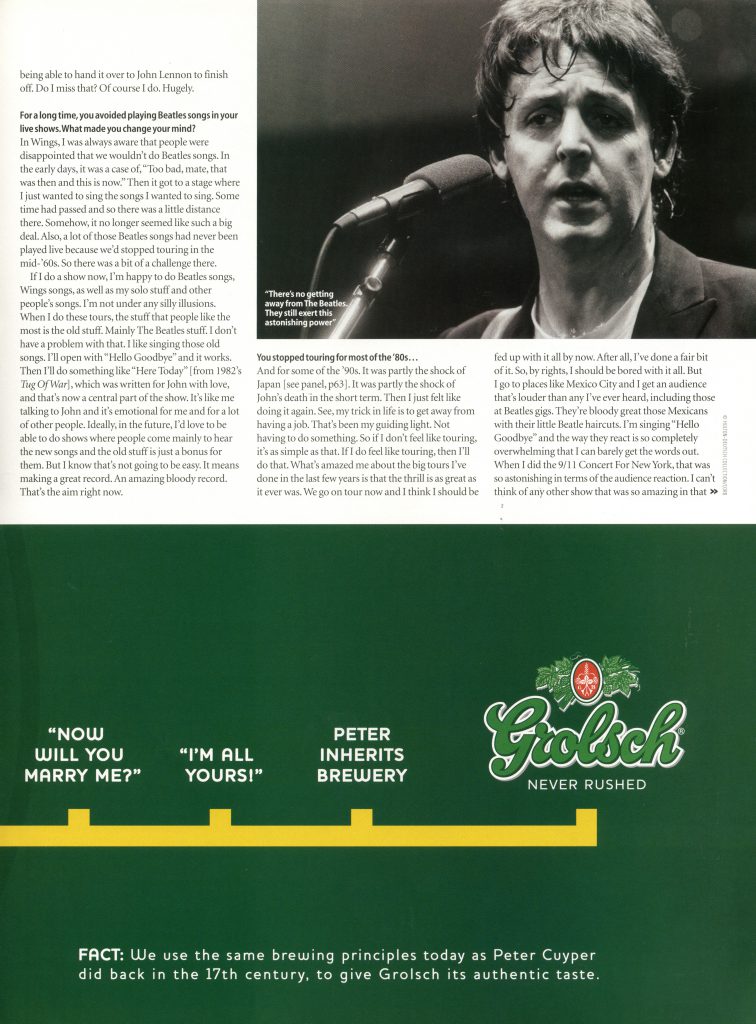

Now I feel I’ve got enough credit for what I did in The Beatles. Even so, there’s no getting away from them. They still exert this astonishing power. They’re like a magnetic force. The more all four of us tried to pull away from them, the harder they pulled us back. And they still do. It continues to amaze me. There’s days when I wake up and have to remind myself that I wrote songs with John Lennon. I know John must have had moments when he thought, “I wrote with Paul McCartney.” It’s fantastic that he was a part of my life in that way. Imagine the luxury of being stuck on a song and being able to hand it over to John Lennon to finish off. Do I miss that? Of course I do. Hugely.

For a long time, you avoided playing Beatles songs in your live shows. What made you change your mind?

In Wings, I was always aware that people were disappointed that we wouldn’t do Beatles songs. In the early days, it was a case of, “Too bad, mate, that was then and this is now.” Then it got to a stage where I just wanted to sing the songs I wanted to sing. Some time had passed and so there was a little distance there. Somehow, it no longer seemed like such a big deal. Also, a lot of those Beatles songs had never been played live because we’d stopped touring in the mid-’60s. So there was a bit of a challenge there.

If I do a show now, I’m happy to do Beatles songs, Wings songs, as well as my solo stuff and other people’s songs. I’m not under any silly illusions. When I do these tours, the stuff that people like the most is the old stuff. Mainly The Beatles stuff. I don’t have a problem with that. I like singing those old songs. I’ll open with “Hello Goodbye” and it works. Then I’ll do something like “Here Today” [from 1982’s Tug Of War], which was written for John with love, and that’s now a central part of the show. It’s like me talking to John and it’s emotional for me and for a lot of other people. Ideally, in the future, I’d love to be able to do shows where people come mainly to hear the new songs and the old stuff is just a bonus for them. But I know that’s not going to be easy. It means making a great record. An amazing bloody record. That’s the aim right now.

You stopped touring for most of the ’80s…

And for some of the ’90s. It was partly the shock of Japan. It was partly the shock of John’s death in the short term. Then I just felt like doing it again. See, my trick in life is to get away from having a job. That’s been my guiding light. Not having to do something. So if I don’t feel like touring, it’s as simple as that. If I do feel like touring, then I’ll do that. What’s amazed me about the big tours I’ve done in the last few years is that the thrill is as great as it ever was. We go on tour now and I think I should be fed up with it all by now. After all, I’ve done a fair bit of it. So, by rights, I should be bored with it all. But I go to places like Mexico City and I get an audience that’s louder than any I’ve ever heard, including those at Beatles gigs. They’re bloody great those Mexicans with their little Beatle haircuts. I’m singing “Hello Goodbye” and the way they react is so completely overwhelming that I can barely get the words out. When I did the 9/11 Concert For New York, that was so astonishing in terms of the audience reaction. I can’t think of any other show that was so amazing in that way. You had a city, a country, in so much shock and fear about terrorism… after this attack on their own land which hadn’t happened since Pearl Harbor. There was such a powerful, emotional feedback that really turned us on as a band. Moments like that, it’s what it’s all about. That’s where the wonder is, I’ve never grown out of that. None of us should. Because it’s powerful shit when people are that into you.

Back in 1967, you were talking about hitting your thirties and wondering whether you’d branch out from pop music, maybe do a little painting, maybe write some poetry. maybe try some classical music. Yet it wasn’t until the ’90s that you properly launched into those creative areas. Why wait so long?

Good question. It’s like I’ve had four lives in a way. There were my school days, there was the whole Beatles period, then my life with Linda and the kids, which included Wings and so on. Maybe that third life ended when Linda passed away and, now, with Heather and everything else, this is like a fourth instalment which, creatively speaking, has already involved things like painting and poetry and classical music. The truth is that, over the last few years. I’ve put out what I’ve really wanted to put out. The fact is that most of those things I was asked to do and I’d have been nuts to have declined those offers. I do tend to go where my fancies take me these days. I’ll go off and do a poetry book. People will undoubtedly say. “Hang about, McCartney, he’s not a poet.” Then again, who the fuck is? Only those people who have the word “poet” branded on their foreheads? Y’know, anyone can be a poet. I’ll do things like that when the urge occurs to me and I’ll give it my best shot every time. The truth is that I wouldn’t still be doing all this stuff if I didn’t want to do it and I wouldn’t be able to carry on doing it if I didn’t have some”screw-you” attitude about it. Because it is my life and I do these things for my own enjoyment. Y’know, I’m not doing all this so people think, “Hey, he’s cool.”

Is it not important to you to be considered “cool”?

To be honest, it’s not that important. Like anyone, I’m not going to complain if someone perceives me or something I’ve done to be cool. But it’s not that being considered cool is some grand ambition of mine. I’m just trying to write a good song and sing well on stage or do a good painting, whatever. As corny as it sounds, I’m also trying to be a good human being Not a Goody Two-Shoes. I’m simply trying to get it right. Because I’m alive, for Christ’s sake. I’m not out to screw anyone. Neither am I a pushover If anyone screws me, then I’ll say, “Fair enough, let’s go to it.” That’s how I’ve always been. We people from Liverpool, we do stick up for ourselves.

What do you say to accusations that you can be something of a tyrant to work with?

A bossy old bugger, you mean? There’ve been times when I have been bossy, particularly on some of the later Beatles albums, I didn’t think of it as bossy at the time. I thought I was helping. The other option was to say, “Fuck this, I can’t be bothered.” On those albums, it sort of fell to me a bit more to take charge. I was conscious that was happening. So I’d back off. Then I’d get George and Ringo saying, “C’mon, produce us, then!” It was a ticklish situation. It was one of those no-win ones. I’ll admit that there were moments when I was treating these world-class musicians like mere band members. In my defence, all I was concerned about was making a great record. They wanted that as much as I did. Since The Beatles, it’s been me very much at the helm, so it’s different. I’ll be working on something and a producer or someone will tell me it’s not good enough. That’s when my back goes up. It’s hard for people to stand up to me like that and, good though it is for them to do that, it’s all too easy for me to say, “Piss off, it’s my record. do what I like. I’ll make as many mistakes as I like. I think it’s good enough and I’m better than you.”

Because you’re Paul McCartney?

Because I’m Paul McCartney. I mean, I’d sooner not play that card. But it does happen. It goes with the territory.

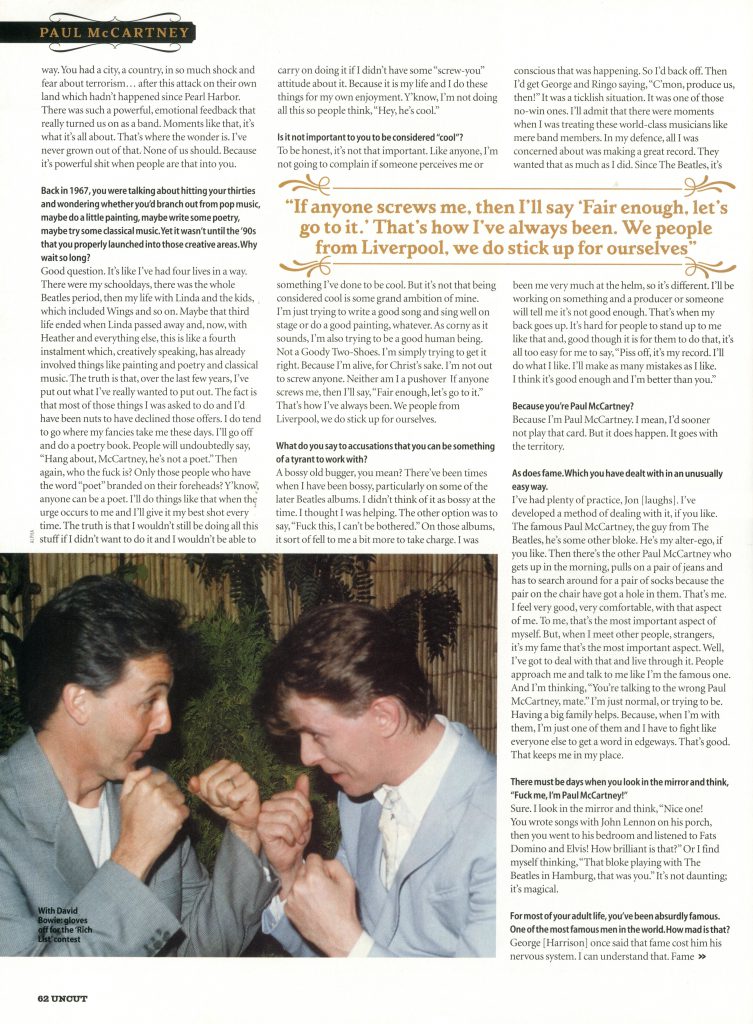

As does fame. Which you have dealt with in an unusually easy way.

I’ve had plenty of practice, Jon [laughs]. I’ve developed a method of dealing with it, if you like. The famous Paul McCartney, the guy from The Beatles, he’s some other bloke. He’s my alter-ego, if you like. Then there’s the other Paul McCartney who gets up in the morning, pulls on a pair of jeans and has to search around for a pair of socks because the pair on the chair have got a hole in them. That’s me. I feel very good, very comfortable, with that aspect of me. To me, that’s the most important aspect of myself. But, when I meet other people, strangers, it’s my fame that’s the most important aspect. Well. I’ve got to deal with that and live through it. People approach me and talk to me like I’m the famous one. And I’m thinking, “You’re talking to the wrong Paul McCartney, mate.” I’m just normal, or trying to be. Having a big family helps. Because, when I’m with them. I’m just one of them and I have to fight like everyone else to get a word in edgeways. That’s good. That keeps me in my place.

There must be days when you look in the mirror and think, “Fuck me, I’m Paul McCartney!”

Sure. I look in the mirror and think, “Nice one! You wrote songs with John Lennon on his porch, then you went to his bedroom and listened to Fats Domino and Elvis! How brilliant is that?” Or I find myself thinking. “That bloke playing with The Beatles in Hamburg, that was you.” It’s not daunting; it’s magical.

For most of your adult life, you’ve been absurdly famous. One of the most famous men in the world. How mad is that?

George Harrison once said that fame cost him his nervous system. I can understand that. Fame happened to us all when we were just kids, really. Being recognised wherever we went, that came really quick. Y’know, I’d go off to somewhere like Greece with Ringo on holiday and nobody would recognise us. We’d have to convince people we were actually quite popular back home. Then we’d have our first hit in Greece and, suddenly, everyone knew who we were. So very quickly, those places we could go where no one knew who we were, they closed down. Until the whole world knew who we were. So there was nowhere, absolutely nowhere, we could go where we weren’t instantly recognisable. And, whatever we did, even if we never made another record, we could never be unfamous again. So it’s sink or swim.

My way through it is being normal. That was always my way and it comes easy because I like living a normal life or at least being normal inside my own head. I used to say to George, “I do miss going on buses,” and he thought I was flaming mad. But I liked sitting on a bus, just watching people, making up stories in my head.

To this day, I like going off on my own and taking the London Underground. If I get recognised, and I usually am, I just deal with it. It’s no big deal. A quick handshake, an autograph, whatever. It’s a small price to pay for the good things that come with fame. That said, there’s not too many of those. Although, take it from me, if you’re well known like I am, you can always be assured that you’ll get a decent poached egg in a posh restaurant.

A fairly blunt question. Do you fear death?

Let’s face it, no one gets out of this one alive. When my number’s up, that will be that. I don’t fancy it particularly. But I don’t fear it, either. It obviously makes a difference that I’ve led this pretty fulfilled life. In terms of death, I’m one of those great optimists in that I completely believe I’ll live well past a hundred. I don’t know why. But I wouldn’t put it past me. We were listening to something of George Harrison’s the other day and Heather said to me, “It must be amazing, to leave something like that behind.” That’s pretty magical.

You must feel so fucking blessed to have had the life you’ve had.

I’d be mad not to feel blessed, wouldn’t I? I’ve been a lucky bugger and so many things that happened to me were pure chance. So much of it was an amazing accident. If I’d never gone to that fete behind the church and met John in 1957. If I hadn’t known the chords to “Twenty Flight Rock” and “Be Bop A Lula” which got me into the band, I might have got the elbow and ended up playing in some little pub band. And so might John, George and Ringo.

That’s the miracle of it right there. The chances of those four people coming together as they did. I’m lucky, very fucking lucky, just to still be vibing and loving life and holding onto my enthusiasm for things.

So when you think back on your life so far…

Y’know, when I do that, so much comes to mind. I think of that journey and this shell that I call my body is the same shell that was this little kid going to school in Liverpool and getting his hair twisted by “Biff” Bowen, the maths teacher. You never forget the names, especially of those who twisted your hair. Or “Dippy” Dewhurst, who used to whack me with a fucking big plimsoll. They were sadists, those people…

Then there’s all the other stuff. Me and John spending whole afternoons walking past shops in Liverpool that had the first closed-circuit cameras, acting like monkeys in the zoo and watching ourselves on the screen. Hitchhiking around Britain with George, asking the police if we could sleep in their cells cos we had nowhere to stay. Recording “Love Me Do” feeling absolutely terrified about getting it right. Being in Paris, hearing that “I Want To Hold Your Hand” had gone to No 1 in America. jumping up and down with excitement. There’s so many great moments.

Then there’s all the personal stuff. Meeting Linda, meeting Heather. Those are the magic little things that make your life. Those moments are full of wonder and you must have that sense of wonder. I’ve never lost that. None of us should ever lose that. It’s precious. Let’s all hold on to that.

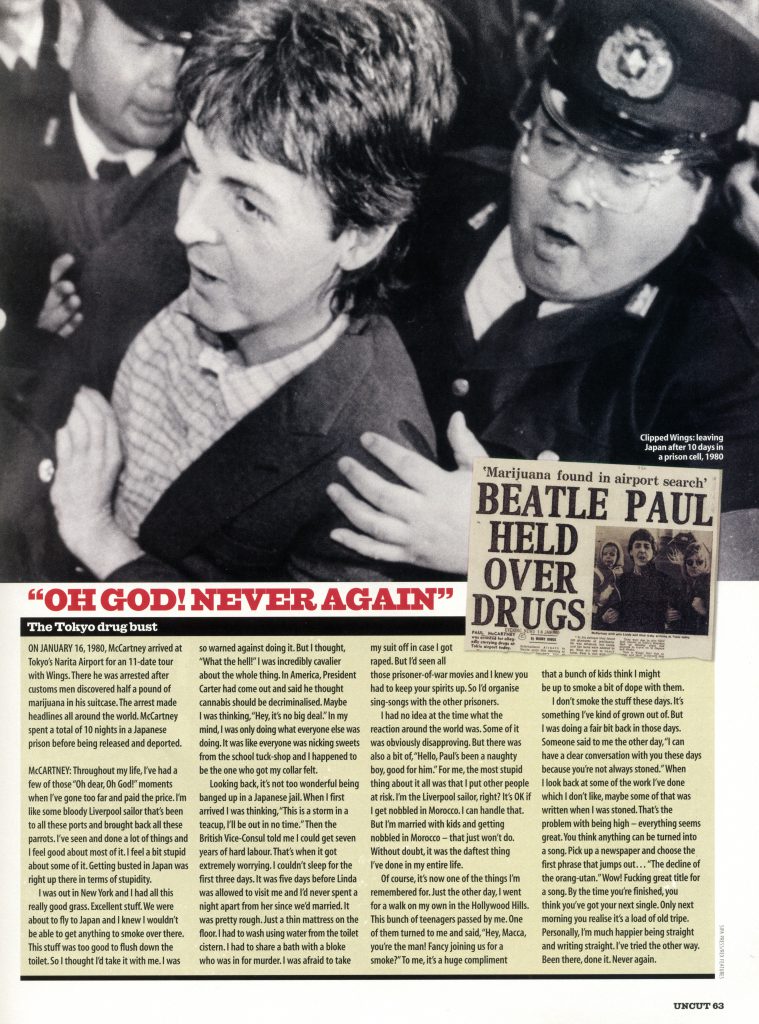

“OH GOD! NEVER AGAIN” – The Tokyo drug bust

ON JANUARY 16, 1980, McCartney arrived at Tokyo’s Narita Airport for an 11-date tour with Wings. There he was arrested after customs men discovered half a pound of marijuana in his suitcase. The arrest made headlines all around the world. McCartney spent a total of 10 nights in a Japanese prison before being released and deported.

MCCARTNEY: Throughout my life, I’ve had a few of those “Oh dear, Oh God!” moments when I’ve gone too far and paid the price. I’m like some bloody Liverpool sailor that’s been to all these ports and brought back all these parrots. I’ve seen and done a lot of things and I feel good about most of it. I feel a bit stupid about some of it. Getting busted in Japan was right up there in terms of stupidity.

I was out in New York and I had all this really good grass. Excellent stuff. We were about to fly to Japan and I knew I wouldn’t be able to get anything to smoke over there. This stuff was too good to flush down the toilet. So I thought I’d take it with me. I was so warned against doing it. But I thought, “What the hell!” I was incredibly cavalier about the whole thing. In America, President Carter had come out and said he thought cannabis should be decriminalised. Maybe I was thinking, “Hey, it’s no big deal.” In my mind, I was only doing what everyone else was doing. It was like everyone was nicking sweets from the school tuck shop and I happened to be the one who got my collar felt.

Looking back, it’s not too wonderful being banged up in a Japanese jail. When I first arrived I was thinking, “This is a storm in a teacup, I’ll be out in no time.” Then the British Vice-Consul told me I could get seven years of hard labour. That’s when it got extremely worrying. I couldn’t sleep for the first three days. It was five days before Linda was allowed to visit me and I’d never spent a night apart from her since we’d married. It was pretty rough. Just a thin mattress on the floor. I had to wash using water from the toilet cistern. I had to share a bath with a bloke who was in for murder. I was afraid to take my suit off in case I got raped. But I’d seen all those prisoner-of-war movies and I knew you had to keep your spirits up. So I’d organise sing-songs with the other prisoners.

I had no idea at the time what the reaction around the world was. Some of it was obviously disapproving. But there was also a bit of, “Hello, Paul’s been a naughty boy, good for him.” For me, the most stupid thing about it all was that I put other people at risk. I’m the Liverpool sailor, right? It’s OK if I get nobbled in Morocco – I can handle that. But I’m married with kids and getting nobbled in Morocco – that just won’t do. Without doubt, it was the daftest thing I’ve done in my entire life.

Of course, it’s now one of the things I’m remembered for. Just the other day, I went for a walk on my own in the Hollywood Hills. This bunch of teenagers passed by me. One t of them turned to me and said, “Hey, Macca, you’re the man! Fancy joining us for a smoke?” To me, it’s a huge compliment that a bunch of kids think I might be up to smoke a bit of dope with them.

I don’t smoke the stuff these days. It’s something I’ve kind of grown out of. But I was doing a fair bit back in those days.

Someone said to me the other day, “I can have a clear conversation with you these days because you’re not always stoned.” When I look back at some of the work I’ve done which I don’t like, maybe some of that was written when I was stoned. That’s the problem with being high-everything seems great. You think anything can be turned into a song. Pick up a newspaper and choose the first phrase that jumps out… “The decline of the orang-utan.” Wow! Fucking great title for a song. By the time you’re finished, you think you’ve got your next single. Only next morning you realise it’s a load of old tripe. Personally, I’m much happier being straight and writing straight. I’ve tried the other way. Been there, done it. Never again.

“SENTIMENTAL BALLADEER? BOLLOCKS” – Was Mccartney the arty Beatle?

For many years, you seemed preoccupied to the point of obsession with correcting the idea that John Lennon was the edgy. experimental Beatle and you were merely a sentimental balladeering softie.

MCCARTNEY: It bothered me and the reason it bothered me was that it was complete bollocks but it became the perceived wisdom. I’ve always thought that the real truth of The Beatles could be found in shades of grey but most people find it easier to deal in the black and white of it all. Especially after John’s death, where these very misleading stereotypes seemed to be set in concrete. Once people had pegged me as the cute Beatle who wrote all the soppy, romantic songs, they could never accept that I wrote “Helter Skelter” or “Why Don’t We Do It In The Road?”

They could never accept that it was me who was responsible for the tape loops on “Tomorrow Never Knows”. People say, “Ah, but John was responsible for ‘Revolution 9’ and that’s the most experimental thing The Beatles ever did.” Well, John was only able to do something like “Revolution 9” because I put a couple of tape recorders together and showed him how to do it. That’s how he came to make Two Virgins with Yoko. John could never have done it otherwise. He was hopelessly untechnical.

It’s ironic that John became known as the avant-garde Beatle considering he was once quoted as saying, “Avant-garde is French for bullshit.”

Well, there you go. In the mid-’60s, John was living out in the suburbs, leading a sort of pipe-and-slippers existence, getting very bored with married life. I was the one who was living in London, going to theatres and art galleries checking out amazing stuff like John Cage and Stockhausen, reading loads of far-out books, hanging out with Harold Pinter and Bertrand Russell, making my own experimental movies, forming my own ideas, which started filtering into the Beatles records.

Most of your more experimental work over the years has either never been officially released (“Carnival of Light, the 14-minute sound collage recorded with George Martin in 1966) or released under pseudonyms (1971 orchestral version of Ram under the name Percy Thrillington; the two albums of ambient dance music made with Killing Joke’s Youth in the ’90s under the name The Fireman.) Why?

Well, I actually wanted “Carnival of Light” to be included on one of the Anthology albums, but the others weren’t too keen. As for the work I’ve done under aliases, it was nothing to do with lacking the confidence to go under my real name. The Fireman thing in particular, that was more like a prank. The anonymous character used was part of the fun. It’s like being a kid and playing hide and seek. I’ll still do things like that.

I’d love to release an album of instrumental Japanese music but I’d call it something mad like “Fuji Pencil Tip Sensual”, give it some far-out design and put it out under some daft name. I like the stupidity of something like that. It’s just a bit of mischief. Doing it for what the Irish call “the craic”. If you can’t do things like that in life, “the craic”. If you can’t do things like that in life, then what’s it about? People might turn around and say those kinds of experiments are silly or they’re beneath someone like me. But I like it and I’m free to do it, so what’s it got to do with anyone else? Whatever I do with my life, I can’t see that it’s anyone else’s business unless you happen to be a parking attendant inspecting my road tax licence.

HE NEEDS TO GET BACK TO WORK. After four-and-a-half hours of intensive question and answer, Uncut’s time is just about up. Leaving just a moment to grab an autograph to mark the occasion. Earlier in the day, McCartney’s personal roadie had warned, “He doesn’t mind signing the odd thing. Best keep it to just the one, though.” In the event, he’s singularly undaunted by the pile of Beatles artefacts placed before him, awaiting his famous signature.

Indeed, the sight of it all produces one last rush of gilt-edged memory. The Revolver sleeve (“Sitting on a sun chair by a pool writing ‘Here, There And Everywhere’ while John was having a kip“). A 1963 photo of The Beatles (“Writing ‘She Loves You’ with John in the back of a van going up to Newcastle“). The White Album (“Ringo’s fingers getting all blistered after the first take of “Helter Skelter’ cos he was drumming so ferociously“).

The moment is so ripe and begs one final question. “Paul,” I ask, “you seem to be as in thrall to The Beatles as anyone. Would you say that’s true?“

“Of course. The Beatles are probably as mysterious and wonderful to me as they are to everyone else,” he says with a firm handshake and a smile. “Probably more so. The mystery and the wonder and the magic of it just go on and on. It never stops. Great, isn’t it?”

Thanks to Geoff Baker, Lillian Marshall and Eddie Klein. Paul McCartney will headline Glastonbury on June 26.

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.