UK Release date : Friday, November 22, 1968

The Beatles (Mono)

By The Beatles • LP • Part of the collection “The Beatles • The original UK LPs”

Last updated on September 22, 2021

UK Release date : Friday, November 22, 1968

By The Beatles • LP • Part of the collection “The Beatles • The original UK LPs”

Last updated on September 22, 2021

Previous album May 17, 1968 • "McGough & McGear (Stereo)" by McGough & McGear released in the UK

Article Nov 13, 1968 • “Yellow Submarine” premiered in the US

Interview Nov 21, 1968 • Paul McCartney interview for Radio Luxembourg

Album Nov 22, 1968 • "The Beatles (Mono)" by The Beatles released in the UK

Album Nov 22, 1968 • "The Beatles (Stereo)" by The Beatles released in the UK

Album Nov 25, 1968 • "The Beatles (Stereo)" by The Beatles released in the US

This album was recorded during the following studio sessions:

“The Beatles” double-album postponed by one week

Early November 1968

A TV ad project to promote “The Beatles” double-album called off

End of October / early November 1968

“The Beatles” double-album announced

Sep 28, 1968

Designing the packaging for the White Album

September - October 1968

2:44 • Studio version • B • Mono

Paul McCartney : Backing vocals, Bass guitar, Drums, Electric guitar, Handclaps, Percussion, Piano, Vocals John Lennon : Backing vocals, Bass, Drums, Electric guitar, Handclaps, Percussion George Harrison : Backing vocals, Drums, Electric guitar, Handclaps, Percussion, Six-string bass guitar George Martin : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Aug 22, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Aug 23, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Aug 23, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

3:56 • Studio version • B • Mono

Paul McCartney : Backing vocals, Bass, Drums, Flugelhorn, Handclaps, Piano John Lennon : Backing vocals, Guitar, Tambourine, Vocals George Harrison : Backing vocals, Handclaps, Lead guitar George Martin : Producer Mal Evans : Backing vocals, Handclaps, Tambourine Barry Sheffield : Recording engineer Jackie Lomax : Backing vocals, Handclaps John McCartney : Backing vocals, Handclaps

Session Recording: Aug 28, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Overdubs: Aug 29, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Overdubs: Aug 30, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Mixing: Oct 13, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

2:18 • Studio version • B • Mono

Paul McCartney : Bass, Piano, Recorder Ringo Starr : Drums, Tambourine John Lennon : Acoustic guitar, Vocals George Harrison : Lead guitar George Martin : Producer Chris Thomas : Producer, Recorder Ken Scott : Recording engineer John Underwood : Viola Eldon Fox : Cello Eric Bowie : Violin Henry Datyner : Violin Reginald Kilbey : Cello Norman Lederman : Violin Ronald Thomas : Violin Keith Cummings : Viola

Session Recording: Sep 11, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Sep 12, 13, 16 - 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Session String overdubs: Oct 10, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Oct 10, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

3:09 • Studio version • B • Mono

Paul McCartney : Bass part on distorted acoustic guitar, Handclaps, Percussion, Vocals Ringo Starr : Conga drum, Drums, Handclaps, Maracas, Percussion John Lennon : Backing vocals, Handclaps, Piano George Harrison : Acoustic guitar, Backing vocals, Handclaps George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Rex Morris : Saxophone (?) Ronnie Scott : Saxophone (?) Unknown musician(s) : Saxophone

Session Recording: Jul 08, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jul 09, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jul 15, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Oct 12, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

0:53 • Studio version • B • Mono

Paul McCartney : Acoustic guitar, Drums, Vocals George Martin : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Aug 20, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Aug 20, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Aug 20, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill

3:14 • Studio version • B • Mono

Paul McCartney : Backing vocals, Bass Ringo Starr : Backing vocals, Drums, Tambourine John Lennon : Acoustic guitar, Organ, Vocals George Harrison : Acoustic guitar, Backing vocals George Martin : Producer Yoko Ono : Backing vocals, Vocals Chris Thomas : Mellotron Ken Scott : Recording engineer Maureen Starkey : Backing vocals

Session Recording: Oct 08, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Oct 08, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Oct 09, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Written by George Harrison

4:45 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Backing vocals, Bass guitar, Organ, Piano Ringo Starr : Drums, Maracas, Tambourine John Lennon : Bass guitar George Harrison : Acoustic guitar, Backing vocals, Hammond organ, Vocals George Martin : Producer Eric Clapton : Lead guitar Ken Scott : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Sep 05, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Sep 06, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Oct 14, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

2:45 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Backing vocals, Bass, Piano Ringo Starr : Drums, Tambourine John Lennon : Backing vocals, Electric guitar, Lead vocal, Organ George Harrison : Backing vocals, Lead electric guitar Chris Thomas : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Sep 24, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Sep 25, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Sep 26, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

2:29 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Bass, Handclaps, Piano, Vocals Ringo Starr : Drums George Harrison : Electric guitar George Martin : Producer Tony Tunstall : French horn Leo Birnbaum : Viola Leon Calvert : Flugelhorn, Trumpet Reginald Kilbey : Cello Barry Sheffield : Recording engineer Bernard Miller : Violin Dennis McConnell : Violin Lou Sofier : Violin Les Maddox : Violin Henry Myerscough : Viola Frederick Alexander : Cello Stanley Reynolds : Trumpet Ronnie Hughes : Trumpet Ted Barker : Trombone Alf Reece : Tuba

Session Recording: Oct 04, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Overdubs: Oct 05, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Mixing: Oct 05, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

2:04 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Backing vocals, Bass, Electric piano Ringo Starr : Drums John Lennon : Lead guitar, Organ, Vocals George Harrison : Lead guitar George Martin : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Oct 08, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Oct 15, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

2:18 • Studio version • B • Mono

Paul McCartney : Acoustic guitar, Backing vocals, Foot taps, Lead vocals George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Jun 11, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Oct 13, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Written by George Harrison

2:04 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Bass, Harmony vocals Ringo Starr : Kick drum, Tambourine John Lennon : Harmony vocals, Tape loops George Harrison : Acoustic guitar, Vocals George Martin : Producer Chris Thomas : Harpsichord, Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer John Underwood : Viola Eldon Fox : Cello Eric Bowie : Violin Henry Datyner : Violin Reginald Kilbey : Cello Norman Lederman : Violin Ronald Thomas : Violin Keith Cummings : Viola

Session Recording: Sep 19, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Sep 20, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Oct 10, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Oct 11, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

3:33 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Acoustic guitar, Vocals Ringo Starr : Drums John Lennon : Accordion, Backing vocals, Harmonica, Six-string bass George Harrison : Backing vocals George Martin : Piano, Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Aug 15, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Aug 15, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Aug 15, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Written by Ringo Starr

3:51 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Bass, Drums, Piano Ringo Starr : Percussion, Piano, Sleigh bell, Vocals George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Ken Scott : Recording engineer Jack Fallon : Violin

Session Recording: Jun 05, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jun 06, Jun 12, Jul 22, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Oct 11, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Why Don't We Do It In The Road?

1:41 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Acoustic guitar, Bass, Handclaps, Lead guitar, Piano, Producer, Vocals Ringo Starr : Drums, Handclaps Ken Townsend : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Oct 09, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Oct 10, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Oct 16-17, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

1:46 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : 'sung bass', Acoustic guitars, Backing vocal, Lead vocal Ringo Starr : Drums John Lennon : Maracas, Skulls Chris Thomas : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Sep 16, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Sep 17, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Sep 26, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

2:57 • Studio version • B • Mono

John Lennon : Acoustic guitar, Vocals George Martin : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Oct 13, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Oct 13, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

2:43 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Bass guitar, Piano, Vocals Ringo Starr : Drums, Handclaps John Lennon : Lead guitar, Vocals George Harrison : Lead guitar, Tambourine Mal Evans : Handclaps Yoko Ono : Backing vocals Chris Thomas : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer Pattie Boyd / Harrison : Backing vocals

Session Recording: Sep 18, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Sep 18, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Sep 18, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

4:01 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Bass Ringo Starr : Drums John Lennon : Backing vocals, Lead guitar, Vocals George Harrison : Lead guitar George Martin : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Aug 13, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Aug 14, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Aug 20, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Aug 14-20, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

2:48 • Studio version • B • Mono

Paul McCartney : Acoustic guitars, Bass drum, Percussion, Vocals George Martin : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer Unknown musician(s) : Two trombones, Two trumpets

Session Recording: Aug 09, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Aug 20, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Oct 12, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Everybody's Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey

2:25 • Studio version • B • Mono

Paul McCartney : Backing vocals, Bass, Hand bell, Maracas Ringo Starr : Drums John Lennon : Guitar, Vocals George Harrison : Backing vocals, Lead guitar George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Ken Scott : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Jun 27, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jul 01, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jul 23, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Oct 12, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

3:15 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Backing vocals, Bass, Guitar, Hammond organ, Piano Ringo Starr : Drums John Lennon : Backing vocals, Rhythm guitar, Vocals George Harrison : Backing vocals, Lead guitar, Tambourine George Martin : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Aug 13, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Aug 21, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Aug 21, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

4:30 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Electric guitar, Vocals Ringo Starr : Drums John Lennon : Backing vocals, Bass guitar, Piano, Tenor saxophone George Harrison : Backing vocals, Electric guitar Mal Evans : Trumpet Chris Thomas : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Sep 09, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Sep 10, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Sep 17, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Written by George Harrison

3:06 • Studio version • B • Mono

Paul McCartney : Backing vocals, Bass, Hammond organ Ringo Starr : Drums George Harrison : Acoustic guitars, Vocals George Martin : Producer Chris Thomas : Piano Ken Scott : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Oct 07, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Oct 08, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Oct 09, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Oct 14, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

4:16 • Studio version • A1 • Mono • Mono made from [A]

Paul McCartney : Backing vocals, Bass, Hammond organ, Piano Ringo Starr : Drums John Lennon : Acoustic guitar, Backing vocals, Lead guitar, Vocals George Harrison : Backing vocals, Lead guitar George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Yoko Ono : Backing vocals, Electronic sound effects Derek Watkins : Trumpet Freddy Clayton : Trumpet Rex Morris : Trombone Peter Bown : Recording engineer Francie Schwartz : Backing vocals Don Lang : Trombone J Power : Trombone Bill Povey : Trombone

Session Recording: May 30, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: May 31 & Jun 4, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jun 21, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Jun 25, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

2:41 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Piano, Vocals Ringo Starr : Drums John Lennon : Lead guitar, Rhythm guitar George Harrison : Bass George Martin : Producer Dennis Walton : Saxophone Rex Morris : Saxophone Barry Sheffield : Recording engineer Ronald Chamberlain : Saxophone Jim Chester : Saxophone Harry Klein : Saxophone Raymond Newman : Clarinet David Smith : Clarinet

Session Recording: Oct 01, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Overdubs: Oct 02, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Overdubs: Oct 04, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Mixing: Oct 05, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Written by George Harrison

2:55 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Bass guitar, Bongos, Harmony vocals Ringo Starr : Drums, Tambourine George Harrison : Lead guitar, Vocals George Martin : Producer Chris Thomas : Electric piano, Organ Ken Scott : Recording engineer Barry Sheffield : Recording engineer Harry Klein : Baritone saxophone Art Ellefson : Tenor saxophone Danny Moss : Tenor saxophone Derek Collins : Tenor saxophone Ronnie Ross : Baritone saxophone Bernard George : Baritone saxophone

Session Recording: Oct 03, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Overdubs: Oct 05, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Overdubs: Oct 11, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs & mixing: Oct 14, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Medley

2:44 • Studio version • B • Mono

Paul McCartney : Bass, Guitar, Piano, Whistling Ringo Starr : Drums, Tambourine John Lennon : Acoustic guitar, Piano, Vocals, Whistling George Harrison : Lead guitar George Martin : Harmonium, Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Ken Scott : Recording engineer

Session Recording: Jul 16, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jul 18, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Sep 17, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Oct 15, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

2:22 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Vocals Ringo Starr : Maracas John Lennon : Percussion Giles Martin : Mixing engineer, Producer Chris Thomas : Producer Ken Scott : Engineer

Session Recording: Sep 16, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Oct 16-17, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

8:22 • Studio version • A1 • Mono • Mono made from [A]

John Lennon : Effects, Producer, Samples, Tape loops, Vocals George Harrison : Samples, Vocals George Martin : Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Yoko Ono : Effects, Samples, Vocals

Session Recording: May 30, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jun 6, 10, 11, 20, 21, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Jun 21, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Aug 26, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

3:14 • Studio version • A • Mono

Ringo Starr : Vocals George Martin : Celesta, Producer Geoff Emerick : Recording engineer Ken Scott : Recording engineer Pat Whitmore : Backing vocals Irene King : Backing vocals Fred Lucas : Backing vocals Mike Redway : Backing vocals Peter Bown : Recording engineer Ingrid Thomas : Backing vocals Val Stockwell : Backing vocals Ross Gilmour : Backing vocals Ken Barrie : Backing vocals Unknown musician(s) : Clarinet, Double bass, French horn, Harp, Three cellos, Three flutes, Three violas, Twelve violins, Vibraphone The Mike Sammes Singers : Backing vocals

Session Recording: Jul 22, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio One, Abbey Road

Session Overdubs: Jul 22, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio One, Abbey Road

Session Mixing: Oct 11, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

There’s always that argument when you’ve got too much stuff. And then it’s like, ‘Well, what would you have lost?’

Paul McCartney, about the White Album’s length, in MOJO 300, November 2018

From Wikipedia:

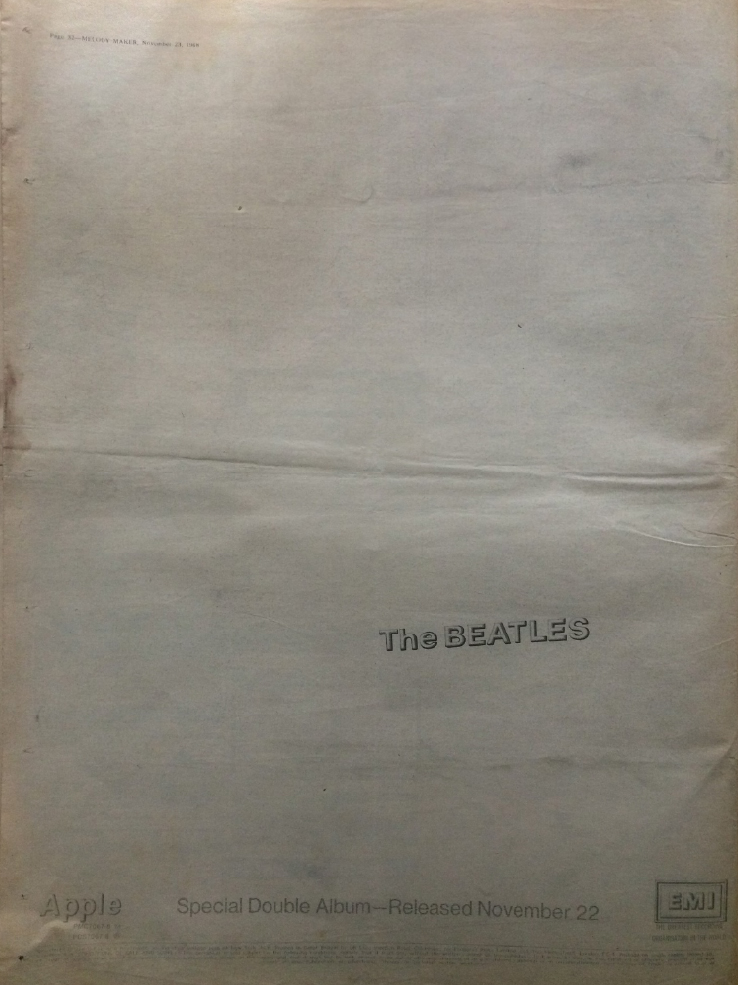

The Beatles, also known as the White Album, is the ninth studio album by English rock group the Beatles, released on 22 November 1968. A double album, its plain white sleeve has no graphics or text other than the band’s name embossed, which was intended as a direct contrast to the vivid cover artwork of the band’s earlier Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Although no singles were issued from The Beatles in Britain and the United States, the songs “Hey Jude” and “Revolution” originated from the same recording sessions and were issued on a single in August 1968. The album’s songs range in style from British blues and ska to tracks influenced by Chuck Berry and by Karlheinz Stockhausen.

Most of the songs on the album were written during March and April 1968 at a Transcendental Meditation course in Rishikesh, India. The group returned to EMI Studios (now known as Abbey Road Studios) in May to commence recording sessions that lasted through to October. During these sessions, arguments broke out among the Beatles, and witnesses in the studio saw band members quarrel over creative differences. Another divisive element was caused by the constant presence of John Lennon’s new partner, Yoko Ono, whose attendance at the sessions broke with the Beatles’ policy regarding wives and girlfriends. After a series of problems, including producer George Martin taking a sudden leave of absence and engineer Geoff Emerick quitting, Ringo Starr left the band briefly in August. The same tensions continued throughout the following year, leading to the eventual break-up of the Beatles in April 1970.

On release, The Beatles received favourable reviews from the majority of music critics, but other commentators found its satirical songs unimportant and apolitical amid the turbulent political and social climate of 1968. The band and Martin have since debated whether the group should have released a single album instead. Nonetheless, The Beatles reached number one on the charts in both the United Kingdom and the United States and has since been viewed by some critics as one of the greatest albums of all time.

Background

By 1968, the Beatles had achieved commercial and critical success. The group’s previous album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, was number one in the UK the previous year and charted for 27 weeks, selling 250,000 copies in the first week after release. Time magazine had written in 1967 that Sgt. Pepper’s constituted a “historic departure in the progress of music – any music,” while the American writer Timothy Leary thought that the band were prototypes of “evolutionary agents sent by God, endowed with mysterious powers to create a new human species.” The band received a negative critical response for the film Magical Mystery Tour, but fan response was nevertheless positive.

Most of the songs for The Beatles were written during a Transcendental Meditation course with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in Rishikesh, India, between February and April 1968. The retreat involved long periods of meditation, conceived by the band as a spiritual respite from all worldly endeavours – a chance, in John Lennon’s words, to “get away from everything.” Both Lennon and Paul McCartney quickly re-engaged themselves in songwriting, often meeting “clandestinely in the afternoons in each other’s rooms” to review their new work. “Regardless of what I was supposed to be doing,” Lennon would later recall, “I did write some of my best songs there.” Author Ian MacDonald said Sgt Pepper was “shaped by LSD“, but the Beatles took no drugs with them to India aside from marijuana, and their clear minds helped the group with their songwriting. The stay in Rishikesh proved especially fruitful for George Harrison as a songwriter, coinciding with his re-engagement with the guitar after two years studying the sitar. The musicologist Walter Everett likens Harrison’s development as a composer in 1968 to that of Lennon and McCartney five years before, although he notes that Harrison became “privately prolific“, given his customary junior status in the group.

The Beatles left Rishikesh before the end of the course. Ringo Starr was the first to leave, as he could not stomach the food; McCartney departed in mid-March, while Harrison and Lennon were more interested in Indian religion and remained until April. According to the author Geoffrey Giuliano, Lennon left Rishikesh because he felt personally betrayed after hearing rumours that the Maharishi had behaved inappropriately towards women who accompanied the Beatles to India, though McCartney and Harrison later discovered this to be untrue and Lennon’s wife Cynthia reported there was “not a shred of evidence or justification“.

Collectively, the group wrote around 40 new compositions in Rishikesh, 26 of which would be recorded in very rough form at Kinfauns, Harrison’s home in Esher, in May 1968. Lennon wrote the bulk of the new material, contributing 14 songs. Lennon and McCartney brought home-recorded demos to the session, and worked on them together. Some home demos and group sessions at Kinfauns were later released on the 1996 compilation Anthology 3.

Recording

The Beatles was recorded between 30 May and 14 October 1968, largely at Abbey Road Studios in London, with some sessions at Trident Studios. The group block-booked time at Abbey Road through to July, and their times at Rishikesh were soon forgotten in the atmosphere of the studio, with sessions occurring at irregular hours. The group’s self-belief that they could do anything led to the formation of a new multimedia business corporation Apple Corps, an enterprise that drained the group financially with a series of unsuccessful projects. The open-ended studio time led to a new way of working out songs. Instead of tightly rehearsing a backing track, as had happened in previous sessions, the group would simply record all the rehearsals and jamming, then add overdubs to the best take. Harrison’s song “Not Guilty” was left off the album despite recording 102 takes.

The sessions for The Beatles marked the first appearance in the studio of Lennon’s new domestic and artistic partner, Yoko Ono, who accompanied him to Abbey Road to work on “Revolution 1” and who would thereafter be a more or less constant presence at all Beatles sessions. Ono’s presence was highly unorthodox, as prior to that point, the Beatles had generally worked in isolation. McCartney’s girlfriend at the time, Francie Schwartz, was also present at some sessions, as were the other two Beatles’ wives, Pattie Harrison and Maureen Starkey.

During the sessions, the band upgraded from 4-track recording to 8-track. As work began, Abbey Road Studios possessed, but had yet to install, an 8-track machine that had supposedly been sitting in a storage room for months. This was in accordance with EMI’s policy of testing and customising new gear extensively before putting it into use in the studios. The Beatles recorded “Hey Jude” and “Dear Prudence” at Trident because it had an 8-track recorder. When they learned that EMI also had one, they insisted on using it, and engineers Ken Scott and Dave Harries took the machine (without authorisation from the studio chiefs) into Abbey Road Studio 2 for the band’s use.

The author Mark Lewisohn reports that the Beatles held their first and only 24-hour session at Abbey Road near the end of the creation of The Beatles, which occurred during the final mixing and sequencing for the album. The session was attended by Lennon, McCartney and producer George Martin. Unlike most LPs, there was no customary three-second gap between tracks, and the master was edited so that songs segued together, via a straight edit, a crossfade, or an incidental piece of music.

Personal issues

The studio efforts on The Beatles captured the work of four increasingly individuated artists who frequently found themselves at odds. Lewisohn notes that several backing tracks do not feature the full group, and overdubs tended to be limited to whoever wrote the song. Sometimes McCartney and Lennon would record simultaneously in different studios, each using different engineers. Late in the sessions, Martin, whose influence over the band had waned, spontaneously left to go on holiday, leaving Chris Thomas in charge of production. Lennon’s devotion to Ono over the other Beatles, and the pair’s addiction to heroin, made working conditions difficult as he became prone to bouts of temper.

Recording engineer Geoff Emerick, who had worked with the group since Revolver in 1966, had become disillusioned with the sessions. At one point, while recording “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da“, Emerick overheard Martin criticising McCartney’s lead vocal performance, to which McCartney replied, “Well you come down and sing it“. On 16 July, Emerick announced that he was no longer willing to work with them and left.

Within the band, according to the author Peter Doggett, “the most essential line of communication … between Lennon and McCartney” had been broken by Ono’s presence on the first day of recording. While echoing this view, Beatles biographer Philip Norman comments that, from the start, each of the group’s two principal songwriters shared a mutual disregard for the other’s new compositions: Lennon found McCartney’s songs “cloyingly sweet and bland“, while McCartney viewed Lennon’s as “harsh, unmelodious and deliberately provocative“. In a move that Lewisohn highlights as unprecedented in the Beatles’ recording career, Harrison and Starr chose to distance themselves part-way through the project, flying to California on 7 June so that Harrison could film his scenes for the Ravi Shankar documentary Raga. Lennon, McCartney and Harrison’s involvement in individual musical projects outside the band during 1968 was further evidence of the group’s fragmentation. In Lennon’s case, the cover of his experimental collaboration with Ono, Two Virgins, featured the couple fully naked – a gesture that his bandmates found bewildering and unnecessary.

On 20 August, Lennon and Starr, working on overdubs for “Yer Blues” in Studio 3, visited McCartney in Studio 2, where he was working on “Mother Nature’s Son“. The positive spirit of the session disappeared immediately, and the engineer Ken Scott later claimed: “you could cut the atmosphere with a knife“. On 22 August, during the session for “Back in the U.S.S.R.“, Starr abruptly left the studio, feeling that his role in the group was peripheral compared to the other members, and was upset at McCartney’s constant criticism of his drumming on the track. Abbey Road staff later commented that Starr frequently turned up to the sessions and sat waiting in the reception area for the others to turn up. In his absence, McCartney played the drums on “Dear Prudence“. Lewisohn also reports that, in the case of “Back in the U.S.S.R.“, the three remaining Beatles each made contributions on bass and drums, with the result that those parts may be composite tracks played by Lennon, McCartney or Harrison.

Lennon, McCartney and Harrison pleaded with Starr to reconsider. He duly returned on 5 September to find his drum kit decorated with flowers, a welcome-back gesture from Harrison. McCartney described the sessions for The Beatles as a turning point for the group, saying “there was a lot of friction during that album. We were just about to break up, and that was tense in itself“, while Lennon later said “the break-up of the Beatles can be heard on that album“. Of the album’s 30 tracks, only 16 have all four band members performing.

Songs

The Beatles contains a wide range of musical styles, which the authors Barry Miles and Gillian Gaar each view as the most diverse of any of the group’s albums. These styles include rock and roll, blues, folk, country, reggae, avant-garde, hard rock and music hall. The production aesthetic ensured that the album’s sound was scaled-down and less reliant on studio innovation, relative to all the Beatles’ releases since Revolver. The author Nicholas Schaffner viewed this as reflective of a widespread departure from the LSD-inspired psychedelia of 1967, an approach that was initiated by Bob Dylan and the Beach Boys and similarly adopted in 1968 by artists such as the Rolling Stones and the Byrds. Edwin Faust of Stylus Magazine described The Beatles as “foremost an album about musical purity (as the album cover and title suggest). Whereas on prior Beatles albums, the band was getting into the habit of mixing several musical genres into a single song, on The White Album every song is faithful to its selected genre. The rock n’ roll tracks are purely rock n’ roll; the folk songs are purely folk; the surreal pop numbers are purely surreal pop; and the experimental piece is purely experimental.“

The only western instrument available to the group during their Indian visit was the acoustic guitar, and thus many of the songs on The Beatles were written and first performed on that instrument. Some of these songs remained acoustic on The Beatles and were recorded solo, or only by part of the group (including “Wild Honey Pie“, “Blackbird“, “Julia“, “I Will” and “Mother Nature’s Son“). […]

Unreleased material

Some songs that the Beatles were working on individually during this period were revisited for inclusion on the group’s subsequent albums, while others were eventually released on the band members’ solo albums. According to the bootlegged album of the demos made at Kinfauns, the latter of these two categories includes Lennon’s “Look at Me” and “Child of Nature” (eventually reworked as “Jealous Guy“); McCartney’s “Junk“; and Harrison’s “Not Guilty” and “Circles“. In addition, Harrison gave “Sour Milk Sea” to the singer Jackie Lomax, whose recording, produced by Harrison, was released in August 1968 as Lomax’s debut single on Apple Records. Lennon’s “Mean Mr. Mustard” and “Polythene Pam” would be used for the medley on Abbey Road the following year.

The Lennon-written “What’s the New Mary Jane” was demoed at Kinfauns and recorded formally (by Lennon, Harrison and Ono) during the 1968 album sessions. McCartney taped demos of two compositions at Abbey Road – “Etcetera” and “The Long and Winding Road” – the last of which the Beatles recorded in 1969 for their album Let It Be. The White Album versions of “Not Guilty” and “What’s the New Mary Jane“, and a demo of “Junk“, were ultimately released on Anthology 3.

“Revolution (Take 20)“, a previously uncirculated recording, surfaced in 2009 on a bootleg. This ten-minute take was later edited and overdubbed to create two separate tracks: “Revolution 1” and the avant-garde “Revolution 9“.

Release

The Beatles was issued on 22 November 1968 in Britain, with a US release following three days later. The album’s working title, A Doll’s House, had been changed when the English progressive rock band Family released the similarly titled Music in a Doll’s House earlier that year. Schaffner wrote in 1977 of the name that was adopted for the Beatles’ double album: “From the day of release, everybody referred to The Beatles as ‘the White Album.’“

“It was great. It sold. It’s the bloody Beatles’ White Album. Shut up!” – Paul McCartney, refuting suggestions that The Beatles should have been a single album

The Beatles was the third album to be released by Apple Records, following Harrison’s Wonderwall Music, and Two Virgins. Martin has said that he was against the idea of a double album at the time and suggested to the group that they reduce the number of songs to form a single album featuring their stronger work, but that the band decided against this. Interviewed for the Beatles Anthology television series in the 1990s, Starr said that he now felt that it should have been released as two separate albums (that he nicknamed “The White Album” and “The Whiter Album“). Harrison felt on reflection that some tracks could have been released as B-sides, but “there was a lot of ego in that band.” He also supported the idea of the double album, to clear out the backlog of songs that the group had at the time. By contrast, McCartney said that it was fine as it was, adding: “It’s the bloody Beatles’ White Album. Shut up!“

Mono version

The Beatles was the last Beatles album to be mixed separately for stereo and mono, though the mono version was issued only in the UK and a few other countries. All but one track exist in official mono mixes; the exception is “Revolution 9“, which was a direct reduction of the stereo master. The Beatles had not been particularly interested in stereo until this album, but after receiving mail from fans stating they bought both stereo and mono mixes of earlier albums, they decided to make the two different. Several mixes have different track lengths; the mono mix/edit of “Helter Skelter” eliminates the fade-in at the end of the song (and Starr’s ending scream), and the fade out of “Yer Blues” is 11 seconds longer on the mono mix.

In the US, mono records were already being phased out; the US release of The Beatles was the first Beatles LP to be issued in stereo only. In the UK, the following album, Yellow Submarine, was the last to be shipped in mono. The mono version of The Beatles was made available worldwide on 9 September 2009, as part of The Beatles in Mono CD boxed set. A reissue of the original mono LP was released worldwide in September 2014.

Packaging

The album’s sleeve was designed by pop artist Richard Hamilton, in collaboration with McCartney. Hamilton’s design was in stark contrast to Peter Blake’s vivid cover art for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and consisted of a plain white sleeve. The band’s name was blind embossed slightly below the middle of the album’s right side, and the cover also featured a unique stamped serial number, “to create“, in Hamilton’s words, “the ironic situation of a numbered edition of something like five million copies“. In 2008, an original pressing of the album with serial number 0000005 sold for £19,201 on eBay. In 2015, Ringo Starr’s personal copy number 0000001 sold for world record $790,000 on auction.

Later vinyl record releases in the US showed the title in grey printed (rather than embossed) letters. The album included a poster comprising a montage of photographs, with the lyrics of the songs on the back, and a set of four photographic portraits taken by John Kelly during the autumn of 1968 that have themselves become iconic. The photographs for the poster were assembled by Hamilton and McCartney, and sorted them in a variety of ways over several days before arriving at the final result.

Tape versions of the album did not feature a white cover. Instead, cassette and 8-track versions (issued on two cassettes/cartridges in early 1969) contained cover artwork that featured high contrast black and white (with no grey) versions of the four Kelly photographs. These two-tape releases were both contained in black outer cardboard slipcase covers that stated “The Beatles” and an Apple logo in gold print. The songs on the cassette version of The Beatles are sequenced differently from the album, in order to equalize the lengths of the tape sides. Two reel-to-reel tape releases of the album were issued, both using the monochrome Kelly artwork. The first, issued by Apple/EMI in early 1969, packaged the entire double-LP on a single tape, with the songs in the same running order as on the LPs. The second release, licensed by Ampex from EMI in early 1970 after the latter ceased manufacture of commercial reel-to-reel tapes, was issued as two separate volumes, and sequenced the songs in the same manner as on the cassette version. The Ampex reel tape version of The Beatles has become desirable to collectors, as it contains edits on eight tracks not available elsewhere, reducing the album’s running time by over seven minutes.

During 1978 and 1979, for the album’s tenth anniversary, EMI reissued the album pressed on limited edition white vinyl in several countries. In 1981, Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab (MFSL) issued a unique half-speed master variation of the album using the sound from the original master recording. The discs were pressed on high-quality virgin vinyl.

The album was reissued, along with the rest of the Beatles catalogue, on compact disc in 1987. It was reissued again on CD in 1998 as part of a 30th anniversary series for EMI, featuring a scaled-down replication of the original artwork. This was part of a reissue series from EMI that included albums from other artists such as the Rolling Stones and Roxy Music. It was reissued again in 2009 in a new remastered edition.

A painting of the band by John Byrne was at an earlier point under consideration to be used as the album’s cover. The piece was later used for the sleeve of the compilation album The Beatles’ Ballads, released in 1980. In 2012 the original artwork was put up for auction.

Contemporary reviews

On release, The Beatles gained highly favourable reviews from the majority of music critics. Others bemoaned its length or found that the music lacked the adventurous quality that had distinguished Sgt. Pepper. According to the author Ian Inglis: “Whether positive or negative, all assessments of The Beatles drew attention to its fragmentary style. However, while some complained about the lack of a coherent style, others recognized this as the album’s raison d’être.“

In The Observer, Tony Palmer wrote that “if there is still any doubt that Lennon and McCartney are the greatest songwriters since Schubert“, the album “should surely see the last vestiges of cultural snobbery and bourgeois prejudice swept away in a deluge of joyful music making“. Richard Goldstein of The New York Times considered the double album to be “a major success” and “far more imaginative” than Sgt. Pepper or Magical Mystery Tour, due to the band’s improved songwriting and their relying less on the studio tricks of those earlier works. In The Sunday Times, Derek Jewell hailed it as “the best thing in pop since Sgt. Pepper” and concluded: “Musically, there is beauty, horror, surprise, chaos, order. And that is the world; and that is what The Beatles are on about. Created by, creating for, their age.” Although he dismissed “Revolution 9” as a “pretentious” example of “idiot immaturity“, the NME‘s Alan Smith declared “God Bless You, Beatles!” to the majority of the album. Jann Wenner of Rolling Stone called it “the history and synthesis of Western music“, and the group’s best album yet. Wenner contended that they were allowed to appropriate other styles and traditions into rock music because their ability and identity were “so strong that they make it uniquely theirs, and uniquely the Beatles. They are so good that they not only expand the idiom, but they are also able to penetrate it and take it further.“

Among the less favourable critiques, Time magazine’s reviewer wrote that The Beatles showcased the “best abilities and worst tendencies” of the Beatles, as it is skilfully performed and sophisticated, but lacks a “sense of taste and purpose“. William Mann of The Times opined that, in their over-reliance on pastiche and “private jokes“, Lennon and McCartney had ceased to progress as songwriters, yet he deemed the release to be “The most important musical event of the year” and acknowledged: “these 30 tracks contain plenty to be studied, enjoyed and gradually appreciated more fully in the coming months.” In his review for The New York Times, Nik Cohn considered the album “boring beyond belief” and said that over half of its songs were “profound mediocrities“. In a 1971 column, Robert Christgau of The Village Voice described the album as both “their most consistent and probably their worst“, and referred to its songs as a “pastiche of musical exercises“. Nonetheless, he ranked it as the tenth best album of 1968 in his ballot for Jazz & Pop magazine’s annual critics poll.

Retrospective assessments

In a 2003 appraisal of the album, for Mojo magazine, Ian MacDonald wrote that The Beatles regularly appears among the top ten in critics’ “best albums of all time” lists, yet it was a work that he deemed “eccentric, highly diverse, and very variable [in] quality“. Rob Sheffield, writing in The Rolling Stone Album Guide (2004), commented that its songs ranged from the Beatles’ “sturdiest tunes since Revolver” to “self-indulgent filler“, and while he derided tracks such as “Revolution 9” and “Helter Skelter“, he acknowledged that picking personal highlights was “part of the fun” for listeners. Writing for MusicHound in 1999, Guitar World editor Christopher Scapelliti described the album as “self-indulgent and at times unlistenable” but identified “While My Guitar Gently Weeps“, “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” and “Helter Skelter” as “fascinating standouts” that made it a worthwhile purchase.

According to Slant Magazine‘s Eric Henderson, The Beatles is a rarity among the band’s recorded works, in that it “resists reflexive canonisation, which, along with society’s continued fragmentation, keeps the album fresh and surprising“. In his review for AllMusic, Stephen Thomas Erlewine said that because of its wide variety of musical styles, the album can be “a frustratingly scattershot record or a singularly gripping musical experience, depending on your view“. He concludes: “None of it sounds like it was meant to share album space together, but somehow The Beatles creates its own style and sound through its mess.“

Among reviews of the 2009 remastered album, Neil McCormick of The Daily Telegraph found that even its worst songs work within the context of such an eclectic and unconventional collection, which he rated “one of the greatest albums ever made“. Writing for Paste, Mark Kemp refuted the White Album’s reputation as “three solo works in one (plus a Ringo song)“; instead, he said, it “benefits from each member’s wildly different ideas” and demonstrates Lennon and McCartney’s considerable versatility as composers, in addition to offering “two of Harrison’s finest moments“. In his review for The A.V. Club, Chuck Klosterman wrote that the album found the band at their best and rated it “almost beyond an A+“.

In 2003, Rolling Stone ranked The Beatles at number 10 on its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time. On the 40th anniversary of the album’s release, Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano wrote that it “remains a type of magical musical anthology: 30 songs you can go through and listen to at will, certain of finding some pearls that even today remain unparalleled“. In 2011, Kerrang! placed the album at number 49 on a list of “The 50 Heaviest Albums Of All Time“. The magazine praised the guitar work in “Helter Skelter“. The album was also included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.

Cultural responses

According to MacDonald, the counterculture of the 1960s analysed The Beatles above and beyond all of the band’s previous releases. The album’s lyrics progressed from being vague to open-ended and prone to misinterpretation, such as “Glass Onion” (e.g., “the walrus was Paul“) and “Piggies” (“what they need’s a damn good whacking“). The release also coincided with public condemnation of Lennon’s treatment of Cynthia, and of his and Ono’s joint projects, particularly Two Virgins. The British authorities similarly displayed a less tolerant attitude towards the Beatles, when London Drug Squad officers arrested Lennon and Ono in October 1968 for marijuana possession, a charge that he claimed was false. In the case of “Back in the U.S.S.R.“, the words were interpreted by Christian evangelist David Noebel as further proof of the Beatles’ compliance in a Communist plot to brainwash American youth.

Lennon’s lyrics on “Revolution 1” were misinterpreted with messages he did not intend. In the album version, he advises those who “talk about destruction” to “count me out“. Lennon then follows the sung word “out” with the spoken word “in“. At the time of the album’s release – which followed, chronologically, the up-tempo single version of the song, “Revolution” – that single word “in” was taken by the radical political left as Lennon’s endorsement of politically motivated violence, which followed the May 1968 Paris riots. However, the album version was recorded first.

Further to the betrayal they had felt at Lennon’s non-activist stance in “Revolution“, New Left commentators condemned The Beatles for its failure to offer a political agenda. The Beatles themselves were accused of using eclecticism and pastiche as a means of avoiding important issues in the turbulent political and social climate. Jon Landau, writing for the Liberation News Service, argued that, particularly in “Piggies” and “Rocky Racoon“, the band had adopted parody because they were “afraid of confronting reality” and “the urgencies of the moment“. Like Landau, many writers among the New Left considered the album outdated and irrelevant; instead, they heralded the Rolling Stones’ concurrent release, Beggars Banquet, as what Lennon biographer Jon Wiener terms “the ‘strong solution,’ a musical turning outward, toward the political and social battles of the day“.

Charles Manson first heard the album not long after it was released. He had already claimed to find hidden meanings in songs from earlier Beatles albums, but in The Beatles he interpreted prophetic significance in several of the songs, including “Blackbird“, “Piggies” (particularly the line “what they need’s a damn good whacking“), “Helter Skelter“, “Revolution 1” and “Revolution 9“, and interpreted the lyrics as a sign of imminent violence or war. He played the album repeatedly to his followers, the Manson family, and convinced them that it was an apocalyptic message predicting an uprising of oppressed races, drawing parallels with chapter 9 of the Book of Revelation.

Sociologists Michael Katovich and Wesley Longhofer write that the album’s release created “a collective appreciation of it as a ‘state-of-the-art’ rendition of the current pop, rock, and folk-rock sounds“. The majority of music critics categorize the White Album as postmodern, emphasizing aesthetic and stylistic features of the album. Other scholars situate all Beatles’ work within a modernist stance, based either on their “artificiality” or their ideological stance of progress through love and peace. Scapelliti cites it as the source of “the freeform nihilism echoed … in the punk and alternative music genres“. […]

Commercial performance

As it was their first studio album in almost eighteen months (and coming after the success of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band) expectations were high at the time of the release of The Beatles. The album debuted at number 1 in the UK on 7 December 1968. It spent seven weeks at the top of the UK charts (including the entire competitive Christmas season), until it was replaced by the Seekers’ Best of the Seekers on 25 January 1969, dropping to number 2. However, the album returned to the top spot the next week, spending an eighth and final week at number 1. The album was still high in the charts when the Beatles’ follow-up album, Yellow Submarine, was released, which reached number 3. In all, The Beatles spent 22 weeks on the UK charts, far fewer than the 149 weeks for Sgt. Pepper. In September 2013 after the British Phonographic Industry changed their sales award rules, the album was declared as having gone platinum, meaning sales of at least 300,000 copies.

In the United States, the album achieved huge commercial success. Capitol Records sold over 3.3 million copies of the White Album to stores within the first four days of the album’s release. It debuted at number 11 on 14 December 1968, jumped to number 2, and reached number 1 in its third week on 28 December, spending a total of nine weeks at the top. In all, The Beatles spent 155 weeks on the Billboard 200. The album has sold over 9.5 million copies in the United States alone and according to the Recording Industry Association of America, The Beatles is the Beatles’ most-certified album at 19-times platinum. […]

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.