Details

- Published: 2005

Timeline

Previous interview Jan 01, 2005 • Interview with Eirik Wangberg

Single May 16, 2005 • "Really Love You (Promo)" by Twin Freaks released in the UK

Concert May 28, 2005 • 5th Annual Adopt-A-Minefield Gala

Interview 2005 • When "I" Becomes "US"

Single Jun 06, 2005 • "Really Love You / Lalula" by Twin Freaks released in the UK

Single Jun 06, 2005 • "Really Love You / Lalula (Promo)" by Twin Freaks released in the UK

Next interview July 2005 • Paul McCartney interview for EMI

Songs mentioned in this interview

-

Officially appears on Chaos and Creation in the Backyard

-

Officially appears on Abbey Road

-

Officially appears on Please Please Me / Ask Me Why

-

Officially appears on Abbey Road

This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

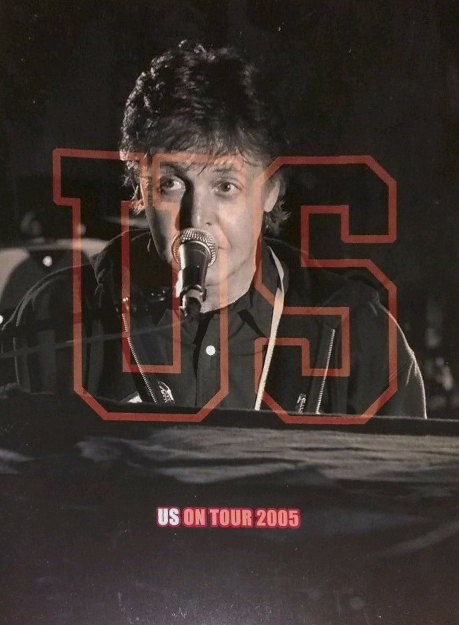

Interview from the US tour book.

The art of Paul McCartney starts in solitude, a writer alone with his inspiration. But the ripples soon spread outwards – to his band, to an audience, to the world. Paul reveals his feelings about that process of sharing, from “the four-headed monster” of The Beatles to the shows we see now. The connecting thread? A sense of togetherness. Interview by Paul Du Noyer.

Q: You were saying the other day the “US” tour is also an “us” tour. There are connections between you and the band, the band and the audience, the tour crew, and wider world. It’s like concentric circles. But at the very center of “us” is a solitary “I” – namely you, writing those songs.

P: Yes. When I write I often hide myself away in the deepest corner, a cupboard or a toilet, or somewhere no one goes. It’s the best place to write.

Q: Do you write for yourself? Or for the rest of us?

P: What I often find with writing a song is that it’s a therapeutic thing. I go and tell my guitar instead of telling a psychiatrist. My guitar is my psychiatrist. In the beginning writing music was just a way to avoid covers. All the other bands knew all the other songs and we wanted something original. I really do think that’s what started Lennon and McCartney, no other motive than that. And then it became a way to earn a living. It wasn’t some hugely artistic motive; it was a pretty mundane motive: just to have songs the other bands couldn’t sing before we came on. And then it was to get a swimming pool, to get a car. Really shallow motives, if you think about it. But then we started to realize that there was a lot more to it. And something I realized was that it was kind of therapeutic. Songwriting was a good moment to go off somewhere secret, the furthest corner of the house you could find – which in our house was the toilet. You’d start telling yourself tales, pulling in stuff that you were thinking and putting it some place, not just in your mind. And that has been a great thing as I’ve gone on; it actually is like having a psychiatric session. If it were to be analyzed you might be getting into some deep psychology that you might not be able to verbalize as well as you’d like to. You put it down in a song with symbolism attached. You’ve framed your thoughts in a way that you can look at them better; it becomes like a painting or a photograph; you can be detached from it, you’ve got something physical. It’s a song, and you’ve captured something. That’s the therapeutic thing.

Q: A moment then arrives when you share your private song for the first time. Does it start with whoever is around?

P: At first it’s whoever’s around. Then you take it to the producer or the band and that’s the next interesting part of the process. It might get knocked around at this point. Some people would say they don’t want it to get knocked around, but I like that process, having been in bands. In a band like The Beatles we would bring in “Please Please Me,” which was a slow Orbison-esque piece, and George Martin suggested that we make it an up-tempo, jangly piece. That’s happened a lot. John brought in “Come Together,” an unwitting copy of a Chuck Berry song, and it was me in that case who had to say, “There’s another way to do this,” and we swamped it out with bass and drums. So that’s the next exciting thing. It doesn’t always change, but something always happens, because now there are other people on it, and all the stuff that makes it into a record instead of just a song.

Q: Did that happen with Nigel Godrich, your producer on the new album?

P: Definitely. Let me tell you just one instance; on the first track, “Fine Line,” there was a mistake, but now when I hear it, I can’t think of it as a mistake at all. That’s not a note I meant to do in the chord. You’ve got like an F sharp and you’ve got a G and it becomes a seventh and you’ve got this F, which shouldn’t be in there, but the response from Nigel was: “Ooh, that’s the juiciest bit of the song.”

Q: Well, you do sing about it being “a fine line between chaos and creation.”

P: Exactly. It is. So that spurred it off and settled us in. And that was the value of Nigel’s production in that I might have thought that F was groovy but avoided it. He pulled me back, and that was that.

Q: And once a song is out in the world you’re getting people’s responses to it. There’s a line in “Anyway” that says, “We can cure each other’s sorrows,” and a lot of new songs seem to offer that kind of encouragement, that healing.

P: I’m interested in “get over it” songs. I do a good line in those – he said, modestly – because I’m interested in that idea. I know lots of songs that have helped me, like “Smile” for instance, or Fred Astaire singing “Let’s Face the Music and Dance”: “There may be troubles ahead…” Fucking right. That should be the backing: “Fucking right.” Remember when that came on in Pennies From Heaven with Bob Hoskins? So I have a deep history with that stuff, whether it’s through my dad or my own personal likes. I was thinking about the new album the other day, and I thought, “What have I done here? Is it all love songs?” Then I thought, “No, it’s not actually. It’s quite different in that respect.” I realized that the very encouraging songs I’ve heard have inspired me to want to do it. Then people have fed back to me, saying, “I was going through school and having the worst time of my life, but your song saved me,” or “I was going through chemotherapy, but your song saved me,” and I have to go, “Whoa, excuse me.” It has become an important part of what I do, but I’m generally trying to reach out in my songs. And when it doesn’t happen it is more in sorrow than anger. I don’t quite know what I’m doing, because I make it all up and I haven’t had lessons, except the lessons of life and of being in The Beatles and my life since then. But there is this magic thing – you have an idea, you put some chords to it and it becomes grander; it becomes music. When I go see the students at LIPA [Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts] the first thing I say is, “I’ve no idea what we’re doing here, but show me your songs, and I’ll give you my opinion. Let’s have a play with it.”

Q: You never seem too dogmatic about the meanings people draw from your songs.

P: I’ve seen this happen a lot, where people have reflected back to me a meaning they’ve seen in it, and even though it’s not my meaning, it’s interesting. Rather than say, “No, that’s wrong,” I’ll say, “That’s great, that’s your interpretation.” Again, it’s like looking at a painting, especially an abstract painting. You can see something very deep in a song that I didn’t mean as a deep thing. That’s happened a lot with me, particularly on older songs. I had someone this year that said to me, “Out of college, money spent… but oh that magic feeling, nowhere to go” [from “You Never Give Me Your Money”]. He said, “Wow!” And I go, “Yeah, it’s nice, but…” And he goes, “No, deep stuff, man!” So I say, “Yeah, OK, I can see there are two ways you can take it.” It’s just you don’t have to be anywhere this afternoon, or in life there’s nowhere to go. It’s pretty Zen if you look at it that way. So that’s why I like to not get too precious. I’m often educated by other people’s views of my songs. If I just said, “No,” then I’d cut out that aspect.

Q: Speaking of the “US” theme, you’ve always liked the “us” that comes of being in a band, haven’t you? You described the moment when The Beatles changed into their Shea Stadium outfits as becoming “the four-headed monster.”

P: That was always a great moment for me, because we weren’t just individuals anymore. We were a group. We were part of a team that looked alike, in our uniforms. I always liked that; it was one of my thrills with The Beatles. And it had gone way back to a Butlins holiday camp I went to when I was 11 in Pwllheli, in North Wales, where I’d seen this singing act that would win the talent show later in the week. They all came out in tartan “twat hats,” as we used to call them, grey crew-neck pullovers, tartan shorts, and a towel under each arm. They just walked on, and that was it for me, it was just, “Yes! That is so cool!” I was always keen for The Beatles to have uniforms, so we didn’t just look like any four guys. It was a unit. The “us” is also the current band. We feel a kinship on tour. At the end of the night it’s just us that take the bow. And then there’s an “us” that takes in the crew. You go out and it’s roughly 140 people, like the circus folk setting up the Big Top. Every night you come in and there are all these guys, and every night you leave and there are all these riggers taking it all down. So that creates a camaraderie that I like a lot. The team feeling.

Q: And then, at the next level up, there is your audience. Do you think a song doesn’t reach its full height until you’ve played it to an audience?

P: I think sometimes it can reach its full height on record, but the feedback from an audience is great. When you do anything it’s always lovely for someone to say that was great. Even if you cook a meal it really helps you. You get that good feeling: “I’m glad you appreciate that.” And it encourages you to do it again. So with playing it live and perhaps seeing people crying to one of your songs, you think, “Wow, I should really stick at this.” Perhaps if you just did it in isolation you wouldn’t know. And I’ve seen some mighty stuff on tours. I find it very touching. And I think it happens more as time goes by, because there are more memories. Now you start to see it across generations, children with their mom, the 25-year-old and her parents, the 50-year-olds, and sometimes there parents too. I like all that, being very family orientated. That’s special. So that’s why I keep throwing it open. You see stuff that you didn’t know about your own work. You see a reflection of how important your work can be. It’s a great reward. And finally there’s an “us” in the world, like there’s an “us” who did Live 8, the people on the bill, in the audience, all the people who believe it’s a good idea to try and help those people born into poverty. We’ll give it a shot. It may not work, but it will throw an awful lot of attention on to the problem. And if it doesn’t work at least we tried. We tried, and I think it’s miraculous that so many people can feel the same. And I think that’s happened since the ’60s.

Q: Do you still identify closely with that generation?

P: Yes. Somehow since the ’60s, there has been a social conscience in all this. There has perhaps been a great idea tying it all together, which to some degree has worked and to some degree is in the process of working. But it’s a really cool idea. Because a lot of “us” from the ’60s are now older than the Prime Minister of Britain, the President of America, or the President of Russia, which is quite a trippy feeling. We talked about it in the ’60s: “One day, our generation will be in power and that’ll be interesting.”

Q: I’m always struck by how excited you get before a new tour.

P: I never take anything for granted. At any minute it can all change. To me it means people want to see me. It really helps, to go into a hall and think, “All you people really tried to get here. You made an effort; it’s not just a school function that you’ve got to attend.” I wouldn’t want to get blase about that, I think it’s cool. I really haven’t become jaded and in a way I’m a bit surprised, because you’d think I’d be a bit fed up with going into the studio, a bit fed up with playing the guitar. But you discover one new chord in the middle of it all and you remember why you’re doing it. When people say, “Do you get fed up touring?” I say, “No, we don’t work, we play music.” It’s very simplistic, but it’s true. How lucky to be playing with this whole thing. We always used to say, “If only your job could be something you like doing.” And a few of us have managed that. But I feel so lucky that I’ve been able to be in music and be with The Beatles and Wings and do what I do now with the band. But also to be involved in this magic experiment, of putting a few words together. It’s lovely to be putting this stuff down, not quite knowing what you’re doing, but at the same time governing yourself to know what you’re doing. It’s a fine line. You’re in a limbo, and I find that exciting.