Wednesday, April 6, 1966

Recording "Tomorrow Never Knows"

For The Beatles

Last updated on October 22, 2023

Wednesday, April 6, 1966

For The Beatles

Last updated on October 22, 2023

April 6 - June 22, 1966 • Songs recorded during this session appear on Revolver (UK Mono)

Recording studio: EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Previous session Jan 05, 1966 • Recording overdubs for "The Beatles At Shea Stadium" TV special

Interview April 1966 • The Beatles interview for The Beatles Monthly Book

Interview April 1966 • Paul McCartney interview for Rave Magazine

Session Apr 06, 1966 • Recording "Tomorrow Never Knows"

Session April 6 - June 22, 1966 • Recording "Revolver"

Session Apr 07, 1966 • Recording "Tomorrow Never Knows", "Got To Get You Into My Life"

Some of the songs worked on during this session were first released on the "Revolver (UK Mono)" LP.

On this day, in a session lasting from 8 pm to 1:15 am, The Beatles started the recording of their next album, “Revolver“. This was the first session for engineer Geoff Emerick as the primary engineer.

Norman Smith had been the primary engineer for all the precedent Beatles albums but had decided to move to the next step of his career and become a producer. Beatles producer George Martin then decided to offer the role to 20-years old Geoff Emerick, who had previously worked for the Beatles but had limited experience as engineer. Geoff accepted, and this day was his very first session in this new role.

Geoff, we’d like you to take over Norman’s job. What do you say?

George Martin – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

“You’re joking, right?” was all I could stammer in response. Blushing furiously, I immediately realized that it was a pathetic reply.

“No, I’m not bloody joking.” George laughed. Sensing my discomfort, he continued in a rather softer voice. “Look, the boys are scheduled to begin work on their new album in two weeks’ time. I’m offering you the opportunity to engineer it for me. Even though you’re young, I think you’re ready. But I need your answer now, today.”

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

The first session for what would ultimately become the album known as Revolver was due to start at 8 P.M. on Wednesday, April 6, 1966. At around six, the two longtime Beatles roadies — Neil Aspinall and Mal Evans — rolled

up in their beat-up white van and began hauling the group’s equipment into EMI’s Studio Three.Earlier that day, I had been pleased to learn that Phil had landed the job of assisting me on the project. Now he and I busied ourselves in the studio, directing the maintenance engineers to set up the microphones in the same standard positions that Norman Smith had always used. […]

“Where’s Norman?” [George Harrison] demanded.

[…] All four pairs of eyes turned to George Martin. The brief pause that followed seemed like an eternity to me. Perched on the edge of my chair in the control room, I stopped breathing.

“Well, boys, I have a bit of news,” Martin replied after a beat or two. “Norman’s out, and Geoff’s going to be carrying on in his place.”

That was it. No further explanation, no words of encouragement, no praise for my abilities. Just the facts, plain and unadorned. I thought I could see George Harrison scowling. John and Ringo appeared clearly apprehensive. But Paul didn’t seem fazed at all. “Oh, well then,” he said with a grin. “We’ll be all right with Geoff; he’s a good lad.” […]

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

Looking back all these years later, it seems to me that the change in engineering seats was probably done with Paul’s advance knowledge and tacit approval. Perhaps it was even done at his instigation. It’s hard to imagine that George Martin would have made that kind of momentous decision without discussing it with any of the group, and he seemed to have the closest relationship with Paul, who was always the most concerned about getting the sound right in the studio. And while I’d like to believe that Paul had fostered a friendship with me since our earliest years of working together because he liked me, it’s also possible that he had an ulterior motive, that he was scouting me out as a possible replacement for Norman.

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

Geoff walked-in green but because he knew no rules he tried different techniques,. And because the Beatles

Jerry Boys, tape operator – From The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions by Mark Lewisohn, 2004

were very creative and very adventurous, they would say yes to everything. The chemistry of George and

Geoff was perfect and they made a formidable team. With another producer and another engineer things

would have turned out quite differently.

Geoff started off by following Norman Smith’s approach because he’d been Norman’s assistant for a while. But he rapidly started to change things around, the way to mike drums or bass, for example. He was always experimenting.

Ron Pender – From The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions by Mark Lewisohn, 2004

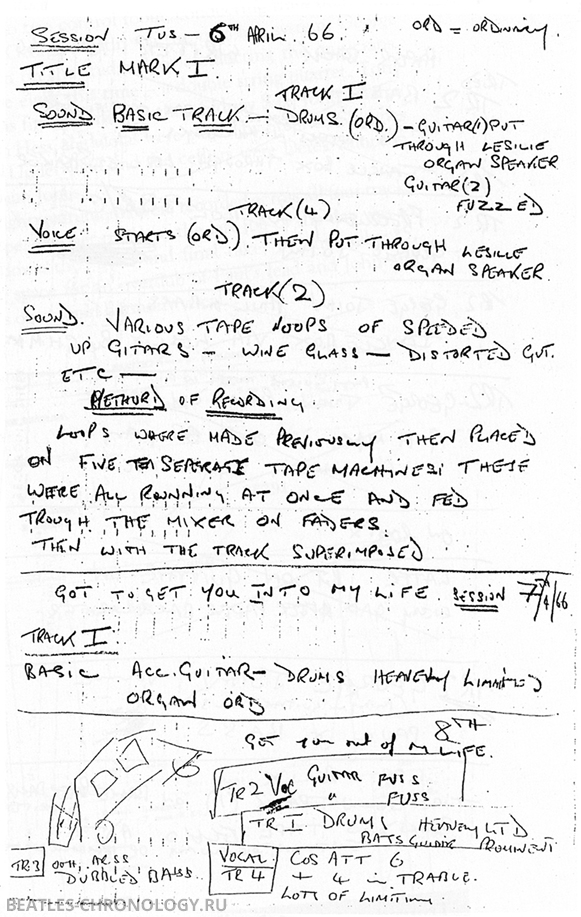

This first session for the “Revolver” album was spent working on what would become the closing song of the album, John Lennon’s song “Tomorrow Never Knows“, worked on at this stage under the working title “Mark I“.

(In The Beatles Monthly Book, September 1966, Neil Aspinall claimed the working title for the track was “The Void”; but this is “Mark I” which appears on the tape boxes, according to Mark Lewisohn, in his book The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions)

The Beatles recorded three takes on this day. For take 1, John Lennon was on organ, George Harrison on guitar and Ringo Starr on drums. John’s vocals were then overdubbed as well as a complementary drum part from Ringo. Take 1 was released on “Anthology 2” in 1996.

With take 1 complete, the song was the subject of two superimpositions. Starr added a drum part, this time recorded at normal speed, and Lennon added his lead vocal, amplified through a Leslie speaker cabinet.

The cabinet provided a flange-like distortion to whatever sound was routed through it. Originally intended for use with the Hammond organ, in The Beatles’ hands it found a wide range of applications.

From The Beatles Recording Reference Manual – Volume 2 – Help! through Revolver (1965-1966) by Jerry Hammack, 2021

Take 2 broke down after 30 seconds.

For Take 3, the backing track was different and included Paul McCartney on bass and Ringo Starr on drums. Take 3 was used as the basic track for the final version.

From Wikipedia:

[…] Geoff Emerick, who was promoted to the role of the Beatles’ recording engineer for Revolver, recalled that the band “encouraged us to break the rules” and ensure that each instrument “should sound unlike itself”. Lennon sought to capture the atmosphere of a Tibetan Buddhist ceremony; he told Martin that the song should sound like it was being chanted by a thousand Tibetan monks, with his vocal evoking the Dalai Lama singing from a mountaintop. The latter effect was achieved by using a Leslie speaker. When the concept was explained to Lennon, he inquired if the same effect could be achieved by hanging him upside down and spinning him around a microphone while he sang into it. Emerick made a connector to break into the electronic circuitry of the Leslie cabinet and then re-recorded the vocal as it came out of the revolving speaker.

Further to their approach when recording Rubber Soul late the previous year, the Beatles and Martin embraced the idea of the recording studio as an instrument on Revolver, particularly “Tomorrow Never Knows”. As Lennon hated doing a second take to double his vocals, Ken Townsend, the studio’s technical manager, developed an alternative form of double-tracking called artificial double tracking (ADT) system, taking the signal from the sync head of one tape machine and delaying it slightly through a second tape machine. The two tape machines used were not driven by mains electricity, but from a separate generator which put out a particular frequency, the same for both, thereby keeping them locked together. By altering the speed and frequencies, he could create various effects, which the Beatles used throughout the recording of Revolver. Lennon’s vocal is double-tracked on the first three verses of the song: the effect of the Leslie cabinet can be heard after the (backwards) guitar solo.

The track includes the highly compressed drums that the Beatles favoured at the time, with reverse cymbals, reverse guitar, processed vocals, looped tape effects, and sitar and tambura drone. In the description of musicologist Russell Reising, the “meditative state” of a psychedelic experience is conveyed through the musical drone, enhancing the lyrical imagery, while the “buzz” of a drug-induced “high” is sonically reproduced in Harrison’s tambura rhythm and Starr’s heavily treated drum sound. Despite the implied chord changes in the verses and repeatedly at the end of the song, McCartney’s bass maintains a constant ostinato in C. Reising writes of the drum part:

Starr’s accompaniment throughout the piece consists of a kind of stumbling march, providing a bit of temporal disruption … [The] first accent of each bar falls on the measure’s first beat and the second stress occurs in the second half of the measure’s third quarter, double sixteenth notes in stuttering pre-emption of the normal rhythmic emphasis on the second backbeat – hardly a classic rock and roll gesture. […]

Geoff Emerick, from “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“:

[…] John always had plenty of ideas about how he wanted his songs to sound; he knew in his mind what he wanted to hear. The problem was that, unlike Paul, he had great difficulty expressing those thoughts in anything but the most abstract terms. Whereas Paul might say, “This song needs brass and timpani,’ John’s direction might be more like “Give me the feel of James Dean gunning his motorcycle down a highway.”

Or, “Make me sound like the Dalai Lama chanting from a mountaintop.”

George Martin looked over at me with a nod as he reassured John. “Got it. I’m sure Geoff and I will come up with something.” Which meant, of course, that he was sure Geoff would come up with something. I looked around the room in a panic. I thought I had a vague idea of what John wanted, but I had no clear sense of how to achieve it. Fortunately, I had a little time to think about it, because John decided to start the recording process by having me make a loop of him playing a simple guitar figure, with Ringo accompanying him on drums. (A loop is created by splicing the end of a section of music to the beginning so that it plays continuously.) Because John wanted a thunderous sound, the decision was made to play the part at a fast tempo and then slow the tape down on playback: this would serve not only to return the tempo to the desired speed but also to make the guitar and drums—and the reverb they were drenched in—sound otherworldly.

The whole time, I kept thinking about what the Dalai Lama might sound like if he were standing on Highgate Hill, a few miles away from the studio. I began doing a mental inventory of the equipment we had on hand. Clearly, none of the standard studio tricks available at the mixing console would do the job alone. We also had an echo chamber, and lots of amplifiers in the studio, but I couldn’t see how they could help, either.

But perhaps there was one amplifier that might work, even though nobody had ever put a vocal through it. The studio’s Hammond organ was hooked up to a system called a Leslie — a large wooden box that contained an amp and two sets of revolving speakers, one that carried low bass frequencies and the other that carried high treble frequencies; it was the effect of those spinning speakers that was largely responsible for the characteristic Hammond organ sound. In my mind, I could almost hear what John’s voice might sound like if it were coming from a Leslie. It would take a little time to set up, but I thought it might just give him what he was after.

“I think I have an idea about what to do for John’s voice,” I announced to George in the control room as we finished editing the loop. Excitedly, I explained my concept to him. Though his brows furrowed for a moment, he nodded his assent. Then he went out into the studio and told the four Beatles, who were standing around impatiently waiting for the loop to be constructed, to take a tea break while “Geoff sorts out something for the vocal.”

Less than half an hour later, Ken Townsend, our maintenance engineer, had the required wiring completed. Phil and I tested the apparatus, carefully placing two microphones near the Leslie speakers. It certainly sounded different enough; I could only hope that it would satisfy Lennon. I took a deep breath and informed George Martin that we were ready to go.

Setting down their cups of tea, John settled behind the mic and Ringo behind his kit, ready to overdub vocals and drums on top of the recorded loop; Paul and George Harrison headed up to the control room. Once everyone was in place and ready to go, George Martin got on the talkback mic: “Stand by… here it comes.” Then Phil started the loop playing back. Ringo began playing along, hitting the drums with a fury, and John began singing, eyes closed, head back.

“Turn off your mind, relax and float downstream…” Lennon’s voice sounded like it never had before, eerily disconnected, distant yet compelling. The effect seemed to perfectly complement the esoteric lyrics he was chanting. Everyone in the control room — including George Harrison — looked stunned.

Through the glass we could see John begin smiling. At the end of the first verse, he gave an exuberant thumbs-up and McCartney and Harrison began slapping each other on the back.

“It’s the Dalai Lennon!” Paul shouted.

George Martin shot me a wry grin. “Nice one, Geoff,’ he said. For someone not prone to paying compliments, that was high praise indeed. For the first time that day, the butterflies in my midsection stopped fluttering. Moments later, the first take was complete and John and Ringo had joined us in the control room to listen to it. Lennon was clearly bowled over by what he was hearing. “That is bloody marvelous,” he kept saying over and over again. Then he addressed me directly for the first time that evening, adopting his finest snooty upper-class accent. “I say, dear boy,” he joked, “tell us all precisely how you accomplished that little miracle.” […]

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

[The Beatles] would relate what sounds they wanted and we then had to go away and come back with a solution. For example, they often liked to doubletrack their vocals but it’s quite a laborious process and they soon got fed up with it. So after one particularly trying night-time session doing just that, I was driving home and I suddenly had an idea…

Ken Townsend – About creating Artificial Double Tracking (ADT)

About “Tomorrow Never Knows“, take 1:

The Beatles had worked almost every day for five years when, after issuing the single Day Tripper/We Can Work It Out, the album Rubber Soul and touring Britain for what turned out to be the last time, they demanded a break from this punishing schedule, taking off the first three months of 1966. Clearly refreshed, and full of yet more innovative ideas, they convened at EMI Studios on 6 April and began work on their seventh album, Revolver, with what turned out to be its closing and most progressive number, Tomorrow Never Knows.

Here was Beatles music the like of which had never before been heard … or made. Here was a dramatic new direction for a musical form that was ceasing to be “pop” and developing into “rock”. Here was a thrilling orgy of sound, all the more inventive for being made within the confines of 1966 four-track technology, less reliant on melody but focusing more on the conveyance of mind-picture on to tape. Tomorrow Never Knows is all of this in a piece of music, the released version (Take 3) being as stunning now as it was 30 years ago. Recorded under its working title Mark I, Take 1, issued [on Anthology 2] for the first time, is notably different but, in its own way, just as compelling.

The Beatles’ music had indeed come a long way in the four years since Love Me Do.

From Anthology 2 liner notes

Now, that’s alternative! That’s cool! Pretty stones, if you ask me! As time went on we had much more freedom. We had much longer to do things. But it actually spurred us on to do some new stuff, so the drum sound on this is, I love it! It’s a really great Ringo sound.

Paul McCartney – From “McCartney 3,2,1” TV documentary, 2021

While they were listening to the first playback of “Tomorrow Never Knows,” John and George Harrison had been excitedly discussing ideas for guitar parts. Harrison eagerly suggested that a tamboura — one of his new collection of Indian instruments — be added. “It’s perfect for this track, John,” he was explaining in his deadpan monotone. “It’s just kind of a droning sound and I think it will make the whole thing quite Eastern.” […]

But my attention was drawn to Paul and Ringo, who were huddled together talking about the drumming. Paul was a musician’s musician — he could play many different instruments, including drums, so he was the one who most often worked with Ringo on developing the drum part. Paul was suggesting that “Ring” (as we usually called him) add a little skip to the basic beat he was playing. The pattern he was tapping out on the mixing console was somewhat reminiscent of the one Ringo had played on their recent hit single “Ticket To Ride.” Ringo said little, but listened intently. As the last of the four Beatles to join, he was used to taking direction from the others, especially Paul. Ringo made an important contribution to the band’s sound — there’s no question about that—but unless he felt strongly about something, he rarely spoke up in the studio.

While Paul was focusing on the drum pattern, I was concentrating on the actual sound of the drums. Norman’s standard mic positioning might have been fine for just any Beatles song, but somehow it seemed too ordinary for the unique nature of this particular track. With Lennon’s words rolling around my brain (“This one’s completely different than anything we’ve ever done before”), I began hearing a drum sound in my head, and I thought I knew how to achieve it. The problem was that my idea was in direct contravention of EMI’s strict recording rules.

Concerned about wear and tear on their expensive collection of microphones, the top studio brass had warned us never to place mics any closer than two feet to drums, especially the bass drum, which put out such a wallop of low frequencies. It seemed to me, though, that if Imoved all the drum mics in closer—say, just a few inches away—we would hear a distinctly different tonal quality, one which I thought would suit the song. Iknew I might get a bollocking from the studio manager for doing so, but my curiosity was piqued: I really wanted to hear what it would sound like. After a moment’s thought, I decided, what the hell. This was the Beatles we were talking about. If I couldn’t try things out at their sessions, I probably would never get the opportunity on anybody else’s session.

Without saying a word, I quietly slipped out to the studio and moved both the snare drum mic and the single overhead mic in close. But before I also moved the microphone that was aimed at Ringo’s bass drum, there was something else I wanted to try, because I felt that the bass drum was ringing too much—in studio parlance, it was too “live.” Ringo, who was a heavier chain smoker than the other three, had a habit of keeping his packet of cigarettes close at hand, right on the snare drum, even while he was playing. In some ways, I think that might have even contributed to his unique drum sound, because it served to slightly muffle the drumskin.

Applying the same principle, I decided to do something to dampen the bass drum. Sitting atep one of the instrument cases was an old woolen sweater—one which had been specially knitted with eight arms to promote the group’s recent film, which was originally called Eight Arms to Hold You before it was renamed Help! I suppose it had since been appropriated by Mal as packing material, but I had a better use for it. As quickly as I could, I removed the bass drum’s front skin — the one with the famous “dropped-T” Beatles logo on it — and stuffed the sweater inside so that it was flush against the rear beater skin. Then I replaced the front skin and positioned the bass drum mic directly in front of it, angled down slightly but so close that it was almost touching.

I returned to the control room, where the four Beatles were gulping down cups of tea, and unobtrusively turned the mixer’s inputs down so that they wouldn’t overload when Ringo resumed playing. Then it was time for me to put into action the final stage of my plan to improve the drum sound. I connected the studio’s Fairchild limiter (a device that reduces peaks in the signal) so that it affected the drum channels alone, and then turned its input up. My idea was to purposely overload its circuitry, again in direct violation of the EMI recording rules. The resulting “pumping” would, I thought, add an extra degree of excitement to the sound of the drums. At the same time, I was saying a silent prayer that the mics wouldn’t be damaged — if they were, my job would probably be on the line. I have to admit to having felt a little bit invulnerable, though: in the back of my mind, I assumed that John Lennon — ecstatic over his new vocal sound and still raving about it to anyone who would listen — would probably rise to my defense if management did threaten to fire me.

As the band reassembled in the studio to make a second attempt at recording the backing track to “Mark I,” I asked Ringo to pound on each of his drums and cymbals. Happily, none of the mics were distorting. In fact, the drums already sounded great to my ears, a combination of the close miking and the Fairchild working away. There was no comment from George Martin, whose attention was diverted elsewhere; he was no doubt thinking about arrangement ideas. My fingers tightened over the controls of the mixing desk; I was tingling with anticipation. So far, so good — but the proof would come when the whole band began playing.

“Ready, John?” asked Martin. A nod from Lennon signaled that he was about to begin his count-in, so I instructed Phil McDonald to roll tape. “… two, three, four,” intoned John, and then Ringo entered with a furious cymbal crash and bass drum hit. It sounded magnificent! Thirty seconds in, someone in the band made a mistake, though, and they all stopped playing. I knew from my assisting days that Lennon would want to start another take immediately — he was always impatient, ready to go — so I quickly announced “take three” on the talkback microphone and the group began Baiing the song again, perfectly this time around.

“I think we’ve got it,” John announced excitedly after the last note died away. George Martin waved everyone into the control room to hear the playback. This time around, I was far less nervous — I felt I had come up with exactly the drum sound that worked best for the song. Ten seconds after starting the tape playing for the four Beatles, I knew my instincts were correct.

“What on earth did you do to my drums?” Ringo was asking me. “They sound fantastic!”

Paul and John began whooping it up, and even the normally dour George Harrison was smiling broadly. “That’s the one, boys,” George Martin agreed, nodding in my direction. “Good work; now let’s knock it on the head for the night.”

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

Work on “Tomorrow Never Knows” would continue on the following day, when tape loops and effects were added.

NEIL’S COLUMN

By the time you read my page, we shall be on our way back from America. And “Revolver” is sure to be at the top of the LP album charts here at home and in the U.S. I wonder if you have decided in your own mind which was the very first “Revolver” track to be recorded when The Beatles started that marathon series of sessions just before Easter? The answer is “The Void”. Don’t start thinking you’ve been fiddled because you can’t find “The Void” on your copy of the album. It was recorded on Wednesday April 6 under that title – but by general agreement it was given the new name “Tomorrow Never Knows” a couple of months later.

DIFFERENT IDEAS

No wonder that particular track has so many different new ideas worked into it. The boys had been storing up all sorts of thoughts for the album and a lot of them came pouring out at that first session! The words were written before the tune and there was no getting away from the fact that the words were very powerful. so all four boys were anxious to build a tune and a backing which would be as strong as the actual lyrics. The basic tune was written during the first hours o f the recording session. […]

From The Beatles Monthly Book – September 1966

Recording • Take 1

Recording • SI onto Take 1

AlbumOfficially released on Anthology 2

Recording • Take 2

Recording • Take 3

The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions • Mark Lewisohn

The definitive guide for every Beatles recording sessions from 1962 to 1970.

We owe a lot to Mark Lewisohn for the creation of those session pages, but you really have to buy this book to get all the details - the number of takes for each song, who contributed what, a description of the context and how each session went, various photographies... And an introductory interview with Paul McCartney!

The Beatles Recording Reference Manual - Volume 2 - Help! through Revolver (1965-1966)

The second book of the Association for Recorded Sound Collections (ARSC)-nominated series, "The Beatles Recording Reference Manual: Volume 2: Help! through Revolver (1965-1966)" follows the evolution of the band from the end of Beatlemania with "Help!" through the introspection of "Rubber Soul" up to the sonic revolution of "Revolver". From the first take to the final remix, discover the making of the greatest recordings of all time.

Through extensive, fully-documented research, these books fill an important gap left by all other Beatles books published to date and provide a unique view into the recordings of the world's most successful pop music act.

If we modestly consider the Paul McCartney Project to be the premier online resource for all things Paul McCartney, it is undeniable that The Beatles Bible stands as the definitive online site dedicated to the Beatles. While there is some overlap in content between the two sites, they differ significantly in their approach.

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.