Thursday, April 7, 1966

Recording "Tomorrow Never Knows", "Got To Get You Into My Life"

For The Beatles

Last updated on November 15, 2023

Thursday, April 7, 1966

For The Beatles

Last updated on November 15, 2023

April 6 - June 22, 1966 • Songs recorded during this session appear on Revolver (UK Mono)

Recording studio: EMI Studios, Studio Three, Abbey Road

Session Apr 06, 1966 • Recording "Tomorrow Never Knows"

Session April 6 - June 22, 1966 • Recording "Revolver"

Session Apr 07, 1966 • Recording "Tomorrow Never Knows", "Got To Get You Into My Life"

Session Apr 08, 1966 • Recording "Got To Get You Into My Life"

Session Apr 11, 1966 • Recording "Got To Get You Into My Life", "Love You To"

Some of the songs worked on during this session were first released on the "Revolver (UK Mono)" LP.

This was the second day of recording the “Revolver” album, continuing the work done on “Tomorrow Never Knows” the previous day, and working on an early version of Paul McCartney’s “Got To Get You Into My Life“.

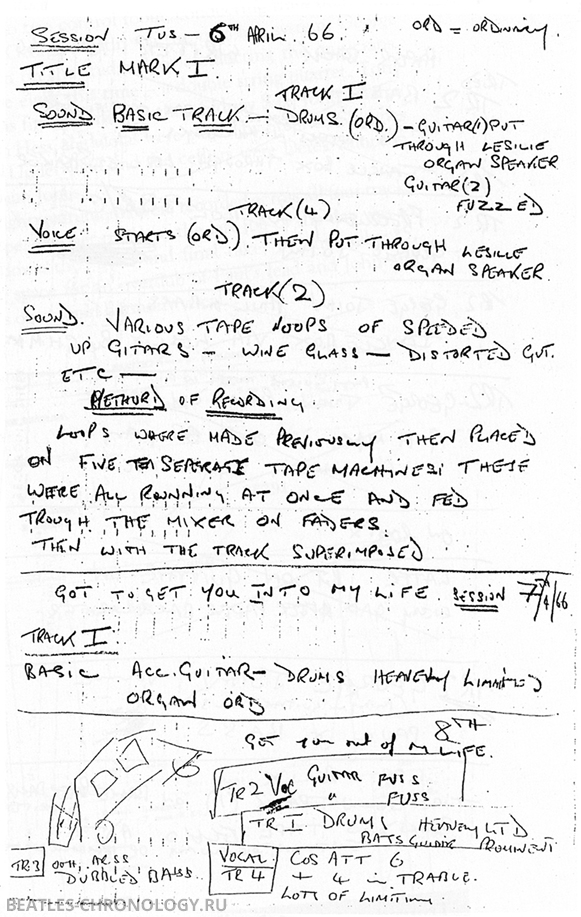

From 2:30 pm to 7:15 pm, The Beatles overlayed various tape loops onto Take 3 of “Tomorrow Never Knows” (under the working title “Mark I“). John Lennon also recorded his lead vocals during this session. From Wikipedia:

[…] The use of ¼-inch audio tape loops resulted primarily from McCartney’s admiration for Stockhausen’s Gesang der Jünglinge. By disabling the erase head of a tape recorder and then spooling a continuous loop of tape through the machine while recording, the tape would constantly overdub itself, creating a saturation effect, a technique also used in musique concrète. The tape could also be induced to go faster and slower. McCartney encouraged the other Beatles to use the same effects and create their own loops. After experimentation on their own, the various Beatles supplied a total of “30 or so” tape loops to Martin, who selected 16 for use on the song. Each loop was about six seconds long.

The overdubbing of the tape loops took place on 7 April. The loops were played on BTR3 tape machines located in various studios of the Abbey Road building and controlled by EMI technicians in Studio Three. Each machine was monitored by one technician, who had to hold a pencil within each loop to maintain tension. The four Beatles controlled the faders of the mixing console while Martin varied the stereo panning and Emerick watched the meters. Eight of the tapes were used at one time, changed halfway through the song. The tapes were made (like most of the other loops) by superimposition and acceleration. According to Martin, the finished mix of the tape loops could not be repeated because of the complex and random way in which they were laid over the music. Harrison similarly described the mix of loops as “spontaneous”, given that each run-through might favour different sounds over another.

Five tape loops are prominent in the finished version of the song. According to author Ian MacDonald, writing in the 1990s, these loops contain the following:

• A recording of McCartney’s laughter, sped up to resemble the sound of a seagull (enters at 0:07)

• An orchestral chord of B♭ major (0:19)

• A Mellotron on its flute setting (0:22)

• A Mellotron strings sound, alternating between B♭ and C in 6/8 time (0:38)

• A sitar playing a rising scalic phrase, recorded with heavy saturation and sped up (0:56).Author Robert Rodriguez writes that the content of the five loops has continued to invite debate among commentators, however, and that the manipulation applied to each of the recordings has made them impossible to decipher with authority. Based on the most widely held views, he says that, aside from McCartney’s laughter and the B♭ major chord, the sounds were two loops of sitar passages, both reversed and sped up, and a loop of Mellotron string and brass voicings. In their 2006 book Recording the Beatles, Kevin Ryan and Brian Kehew list two loops of sitar recordings yet, rather than Mellotron, list a mandolin or acoustic guitar, treated with tape echo. Rather than revert to standard practice by having a guitar solo in the middle of the song, the track includes what McCartney described as a “tape solo”. This section nevertheless includes a lead guitar part played by Harrison and recorded with the tape running backwards, to complement the sounds. […]

Geoff Emerick, from “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“:

Inspired by the initial loop that John and Ringo had created during the first night of recording “Tomorrow Never Knows,” Paul had gone home and sat up all night creating a whole series of short tape loops specifically for the song, which he dutifully presented to me in a little plastic bag when he returned for the next day’s session. We began the second evening’s work by having Phil McDonald carefully thread each loop onto the tape machine, one at a time, so that we could audition them. Paul had assembled an extraordinary collection of bizarre sounds, which included his playing distorted guitar and bass, as well as wineglasses ringing and other indecipherable noises. We played them every conceivable way: proper speed, sped up, slowed down, backwards, forwards. Every now and then, one of the Beatles would shout, “That’s a good one,” as we played through the lot. Eventually five of the loops were selected to be added to the basic backing track.

The problem was that we had only one extra tape machine. Fortunately, there were plenty of other machines in the Abbey Road complex, all interconnected via wiring in the walls, and all the other studios just happened to be empty that afternoon. What followed next was a scene that could have come out of a science fiction movie — or a Monty Python sketch. Every tape machine in every studio was commandeered and every available EMI employee was given the task of holding a pencil or drinking glass to give the loops the proper tensioning. In many instances, this meant they had to be standing out in the hallway, looking quite sheepish. Most of those people didn’t have a clue what we were doing; they probably thought we were daft. They certainly weren’t pop people, and they weren’t that young either. Add in the fact that all of the technical staff were required to wear white lab coats, and the whole thing became totally surreal.

Meanwhile, back in the control room, George Martin and I huddled over the console, raising and lowering faders to shouted instructions from John, Paul, George, and Ringo. (“Let’s have that seagull sound now!” “More distorted wineglasses!”) With each fader carrying a different loop, the mixing desk acted like a synthesizer, and we played it like a musical instrument, too, carefully overdubbing textures to the prerecorded backing track. Finally we completed the task to the band’s satisfaction, the white-coated technicians were freed from their labors, and Paul’s loops were retired back to the plastic bag, never to be played again.

We had no sense of the momentousness of what we were doing — it all just seemed like a bit of fun in a good cause at the time — but what we had created that afternoon was actually the forerunner of today’s beat- and loopdriven music. If someone had told me then that we had just invented a new genre of music that would persist for decades, I would have thought he was crazy.

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

We got machines from all the other studios, and with pencils and the aid of glasses got all the loops to run. We might have had twelve recording machines where we normally only needed one to make a record. We were running with those loops all fed through the recording desk.

Paul McCartney – From beatlesebooks.com

We did a live mix of all the loops. All over the studios we had people spooling them onto machines with pencils while Geoff did the balancing. There were many other hands controlling the panning.

It is the one track, of all the songs The Beatles did, that could never be reproduced: it would be impossible to go back now and mix exactly the same thing: the ‘happening’ of the tape loops, inserted as we all swung off the levers on the faders willy-nilly, was a random event.

George Martin

It was Paul, actually, who experimented with his tape machine at home, taking the erase-head off and putting on loops, saturating the tape with weird sounds. He explained to the other boys how he had done this and Ringo and George would do the same and bring me different loops of sounds, and I would listen to them at various speeds, backwards and forwards, and select some.

That was a weird track, because once we’d made it we could never reproduce it. All over the EMI studios were tape machines with loops on them, and people holding the loops at the right distance with a bit of pencil The machines were going all the time, the loops being fed to different faders on our control panel, on which we could bring up the sound at any time, as on an organ. So the mix we did then was a random thing that could never be done again. Nobody else was doing records like that at that time – not as far as I knew.

George Martin – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

People tend to credit John with the backwards recordings, the loops and the weird sound effects, but the tape loops were my thing. The only thing I ever used them on was Tomorrow Never Knows. It was nice for this to leak into the Beatle stuff as it did.

We ran the loops and then we ran the track of Tomorrow Never Knows and we played the faders, and just before you could tell it was a loop, before it began to repeat a lot, I’d pull in one of the other faders, and so, using the other people, ‘You pull that in there,’ ‘You pull that in,’ we did a half random, half orchestrated playing of the things and recorded that to a track on the actual master tape, so that if we got a good one, that would be the solo. We played it through a few times and changed some of the tapes till we got what we thought was a real good one.

I think it is a great solo. I always think of seagulls when I hear it. I used to get a lot of seagulls in my loops; a speeded-up shout, hah ha, goes squawk squawk. And I always get pictures of seasides, of Torquay, the Torbay Inn, fishing boats and puffins and deep purple mountains. Those were the slowed-down ones.

Paul McCartney – From “Many Years From Now” by Barry Miles, 1998

You know that you could talk to George [Martin] about these things. ‘George, what if we played it backwards and then what if we did that?’ ‘Well…’ and he’d sort of go along with it. Because a lot of other producers on EMI, I’m sure they would have just said, ‘Another time, let’s get the record done,’ y’know, and wouldn’t have been interested in backwards noises or tape loops. I had an old tape recorded that you could put, make a loop instead of the two reels of tape. You could (make) a little loop that would go round and round and round. There’s a little button that says, ‘superimpose.’ It keeps recording forever and ever and ever and ever. Now, once you’ve gone ’round, what was there is still there but it’s now going in the background a bit. It’s a bit of an art because you’ve got to know when to stop…you gotta sort of stop soon because you’re gonna wipe out those original ideas.

Paul McCartney – From “McCartney 3,2,1” TV documentary, 2021

The final overdubs for “Tomorrow Never Knows” would be recorded on April 22, 1966.

After a one-hour break, The Beatles worked on “Got To Get You Into My Life“, from 8:15 pm to 1:30 am, recording five takes of the basic track, with Paul McCartney on acoustic guitar and lead vocals, John Lennon and George Harrison on backing vocals and tambourine, Ringo Starr on drums and George Martin on organ, according to “The Beatles Recording Reference Manual: Volume 2: Help! through Revolver (1965-1966)” by Jerry Hammack.

In the “Revolver (2022)” book, the credits are different: Paul is on vocal and organ, John on backing vocals, George on backing vocals and acoustic guitar and Ringo on drums

The organ was only used in the song’s introduction, and only Take 5 had vocals.

From Wikipedia:

Though officially credited to Lennon–McCartney, McCartney was primarily responsible for the writing of the song, to which he also contributed lead vocals. It was recorded at Abbey Road Studios between 7 April and 17 June 1966 and evolved considerably between the first takes and the final version released on album. The song seems to have been hard to arrange until the soul-style horns, strongly reminiscent of the Stax’ Memphis soul and Motown sound, were introduced. The original version of the track, taped on the second day of the Revolver sessions, featured an arrangement that included harmonium and acoustic guitar, and a partly a-cappella section (repeating the words “I need your love”) sung by McCartney, John Lennon and George Harrison. In the description of author Robert Rodriguez, relative to the “R&B-styled shouter” that the band completed in June, this version was “more Haight-Ashbury than Memphis”. Author Devin McKinney similarly views the early take as “radiat[ing] peace in a hippie vein”, and he recognises the arrangement as a forerunner to the sound adopted by the Beach Boys over 1967–1968 on their albums Smiley Smile and Wild Honey.

Take 5 was released on Anthology 2 in 1996.

The arrangement of Paul’s Got To Get You Into My Life altered significantly from first studio outing to last, the released version (Take 9) being layered with vocals and brass in addition to the group’s own rhythm tracks. When the song was first aired in the studio, on 7 April, the Beatles recorded Takes 1 to 5, marking the last of these “best” (temporarily, as it turned out) and overdubbing vocals for the first time. The result is a piece of work scarcely comparable to the released version, with its different musical structure and some alternative lyrics. By the end of this session two of the tracks on the four-track tape had been filled, and doubtless the vacant ones would also have been completed had the Beatles decided to press on. Instead, returning to Abbey Road the next day, they shelved Take 5 and moved on the song in a different direction.

From Anthology 2 liner notes

At the end of the session, take 5 was considered the best take so far, but the track would be remade the following day.

NEIL’S COLUMN

[…] Once the boys started bringing out their special sound tapes the studio technicians just didn’t know what was going on! Because for “Tomorrow Never Knows” five different “tape loops” were used to create all those far-out noises. “Tape loops” are just very short lengths of recording tape and all the Beatles had been creating strange electronic noises with all the equipment they’ve got in their own homes. Paul was the most prolific in the tape-making field and he brought along some fantastic home-made sounds, which were incorporated into the finished version of “Tomorrow Never Knows”. But it wasn’t as simple as that – the “tape loops” were recorded at different speeds and even backwards to achieve all the weird and wonderful effects they wanted. […]

From The Beatles Monthly Book – September 1966

[…] Paul’s greatest hobby at the moment is tape recording. He has a room which is stacked with recording equipment. It’s loaded with special devices and Paul spends hours twiddling complicated sets of controls, a great big pair of headphones strapped about his ears. He’s become an expert at recording and double-tracking — he’ll start with a basic sound on one tape, re-record something over it and then repeat the process umpteen times using two tape decks. He specialises in curious space noises and electronic music. Once he set up a line of tumblers, each with a different amount of water in, and recorded the sound made by running his fingers around the rim of each one. […]

From The Beatles Monthly Book – April 1966

Recording • SI onto take 3

Recording • Take 1

Recording • Take 2

Recording • Take 3

Recording • Take 4

Recording • Take 5

AlbumOfficially released on Anthology 2

The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions • Mark Lewisohn

The definitive guide for every Beatles recording sessions from 1962 to 1970.

We owe a lot to Mark Lewisohn for the creation of those session pages, but you really have to buy this book to get all the details - the number of takes for each song, who contributed what, a description of the context and how each session went, various photographies... And an introductory interview with Paul McCartney!

The Beatles Recording Reference Manual - Volume 2 - Help! through Revolver (1965-1966)

The second book of the Association for Recorded Sound Collections (ARSC)-nominated series, "The Beatles Recording Reference Manual: Volume 2: Help! through Revolver (1965-1966)" follows the evolution of the band from the end of Beatlemania with "Help!" through the introspection of "Rubber Soul" up to the sonic revolution of "Revolver". From the first take to the final remix, discover the making of the greatest recordings of all time.

Through extensive, fully-documented research, these books fill an important gap left by all other Beatles books published to date and provide a unique view into the recordings of the world's most successful pop music act.

If we modestly consider the Paul McCartney Project to be the premier online resource for all things Paul McCartney, it is undeniable that The Beatles Bible stands as the definitive online site dedicated to the Beatles. While there is some overlap in content between the two sites, they differ significantly in their approach.

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.