March 2003

Photo session with Chris Floyd

Last updated on December 6, 2025

March 2003

Last updated on December 6, 2025

Location: London Arena • London • UK

Previous article Oct 28, 2002 • Paul McCartney cancels concert in Australia

Interview Unknown date • Paul McCartney interview for Viva!

Concert Feb 22, 2003 • Private concert

Article March 2003 • Photo session with Chris Floyd

Live album Mar 17, 2003 • "Back In The World" by Paul McCartney released in the UK

Live album Mar 17, 2003 • "Back In The World" by Paul McCartney released in the US

Next article April 2003 • MPL Communications buys rights to Carl Perkins' catalogue

In March 2003, British photographer Chris Floyd was invited to photograph Paul McCartney during his rehearsals for the European leg of the “Back In The World” tour.

Photographs taken during this photo shoot were published in …

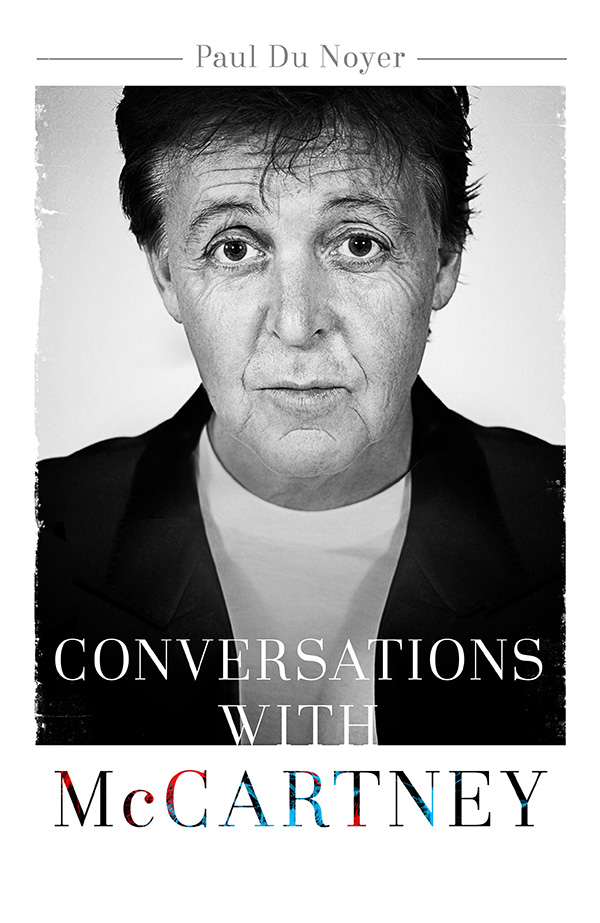

In 2015, the book “Conversations With McCartney” written by Paul du Noyer featured a photo from this session on its cover.

So, I grew up as a huge Beatles fan — borderline obsessive in my teens. And probably the very first photograph I ever saw that made me realize photography didn’t have to be weddings was a David Bailey portrait of John Lennon and Paul McCartney. 1965. Hasselblad, square frame, white background, dark clothes — very classically austere, monochromatic. And I saw that probably aged about 14, maybe 15, and it just knocked me for six. I thought it was the coolest thing I’d ever seen. And I realized photography could be a portal to meeting amazing people. That’s my sort of photographic ground zero.

So it’s 2003. I am 34, living in New York, and I get commissioned to photograph Yoko Ono. That goes very well. At some point after that they call and say: “We’ve got a shoot with McCartney. Two covers — a Yoko cover and a Paul cover. But Paul’s in London so we were going to get a London photographer… however, we really like what you did with Yoko. If you’d like to do it, it’s yours. But we cannot afford to pay your flight from New York to London. We can’t justify it.” And I said: “I’ll pay my own flight. I just want to do it.”

It was probably two weeks between them offering me the job and the shoot date. And all I did for those two weeks was think about it — morning, noon and night. I was incredibly nervous, because it represented the peak of everything I wanted to do, the thing that inspired me in the first place. A dream come true.

The shoot was going to be at the London Arena. He was rehearsing for an upcoming world tour. The arena floor would be empty — effectively a huge studio space. I was given two hours to set up. I’m nervous thinking about it. What could possibly go wrong? I’m nervous to this day on every shoot — something always goes wrong.

We set up. Two assistants — extremely extravagant for me at the time. White backdrop and grey backdrop.

At 10:00 he arrives. His band is already on stage warming up, playing a classic rock ’n’ roll song — Jerry Lee Lewis or Buddy Holly. Paul comes in and he just can’t resist the lure of the classic rock ’n’ roll jam. It’s his domain. He says: “Give me a minute, I’ll be with you in a minute,” jumps on stage, picks up his bass, and joins in. And then… he just carries on. They go into rehearsals.My 10:00 just goes past… and we sit there for hours and hours.

At first it felt like such a privilege — the whole road crew there, full tour rehearsal. They did probably 30 songs, and I knew all of them. I remember phoning my mum at one point, holding the phone up so she could hear.

Eventually, around 4 pm, we finally get him. He comes onto the little set we built and says: “Okay, where do you want me? What do you need?” But I was so flustered — I’d been waiting so long I’d gone into shutdown, like a video game avatar waiting to be activated.

Anyway, he comes to where we set up. We’d been promised half an hour. I start shooting — medium format, Mamiya RZ, about a roll and a half — and then he claps his hands together: “Right — you’ve got enough, haven’t you?” I said, “I thought we had half an hour.” He says he has to go to BBC radio for a live broadcast — he can’t be late. I said, “But we were told half an hour…” He says: “I know, I’m so sorry. I know.” I said: “I came all the way from New York for this.” He says: “What do you mean, you came from New York?” I explain I live in New York. He says: “You came all the way from New York for this?” Then he starts reminiscing about the Beatles’ first visit to New York — amazing moment.

Then he asks: “When are you going back?” This is Friday. “I’m going back Tuesday.” “What are you doing Monday?” “Nothing.” “Come back Monday. I’ll give you half an hour. Leave all your stuff here — we’ve got security.” And I said “Is that a deal?” And he said, “Yes, it’s a deal.”

We shook hands on it. His car was idling on the arena floor. We parted on very good, friendly terms. I saluted him: “Have a good weekend, Paul. See you Monday.” “Yeah, have a good weekend. See you Monday.” For a moment, I felt like I had a work colleague called Paul McCartney. […]

So Monday: we come back. I switch to a grey backdrop. He arrives wearing a white t-shirt — doesn’t work on grey. I ask if he has anything dark. Luckily he has a full tour wardrobe. He puts on a blue crew neck. Then he says: “So what are you after? Cause you know my wife was a photographer” Very lovely moment.

I tell him I want something like the Avedon “Mount Rushmore” portrait. I was amazing cause for me this was such an iconic picture, that’s in the cannon. And he looks puzzled, tries to remember: “I don’t remember that one.” I was awe struck that something so iconic culturally could be barely known to its subject.

I didn’t say it to him, but I had this acute awareness of how focused and ambitious he has been his entire life. I genuinely believe he’ll be held in the same esteem as Shakespeare, Dickens, Mozart, Beethoven, George Gershwin, Hemingway. He’s at that level.

So, I wanted to capture a portrait commensurate with that level of determination and drive — seriousness, intensity. But it’s hard to get that from someone who’s had their portrait taken 763,000 times. […] You have to become a curiosity to your subject — make yourself worthy of their attention, an act they want to watch a little longer.

Our previous encounter helped — he was intrigued that I came from New York. So we start. He’s in his dark jumper. But he’s on autopilot — classic Macca: thumbs-up, lighthearted expressions. This is not the picture I’m trying to get. I’m trying to get that determined, focused, driven thing. In my head it felt like being in the cockpit of a plane going down — the ground getting bigger in the window. He offers me a lighthearted pose and I say: “No, no. Do less. Do less. You are an honest man who can be certain of his achievements. Just give me that.”

He replies: “What’s the matter? Don’t you like a bit of whimsy?”

It’s March 2003 — the first week of the Gulf War. I say: “Not when there’s a war on, Paul.” We don’t have time for the Donald Duck fancy dress party when there’s a war on. It’s a sort of a bit like that, you know. But I think he interpreted that as me really kind of castigating him for his frivolity, which is not what I meant at all. It was meant as a kind of light-hearted aside, but he took it, I think the wrong way.

And his whole demeanour just completely changed. And I just saw this. It was like the everything he’s been up to that point just kind of suddenly melted away. And his other face emerged quite quickly. And it became the portrait I got.

And I thought, now, I needed to clear the air, I needed to make friend with him again. […] I said, “just close your eyes and relax.” I shot three frames of him with his eyes closed — all identical. Thirty percent of a roll. But I couldn’t think of anything else to do.

And I knew I had it. The sixth and seventh frames — I knew instantly. Sometimes you just know: this is really something. The relief and euphoria washes over you — you’ve gone through the fire and come out with something worth trying for.

Chris Floyd – From He Photographed Paul McCartney And Upset The Beatle – YouTube

Late March 2003, a Friday, I am living in New York City. Been here for almost three years, my trips back to London confined to Christmas and the two months in the summer when the concrete and glass serves only to exacerbate the fetid and oppressive humidity of the place, rat people darting from one air conditioned refuge to another.

All my life, The Beatles have been here. They saturate my earliest memories. A babysitter playing “Help” on my dad’s stereo that lived inside a glass cabinet. Just the sound of “The Night Before”, the reverb, colours my impression of the sixties as a time of space, light and opportunity. Young men bombing about a deserted late-night London in Minis, with beautiful girls in miniskirts and knee high boots, before going back to Habitat flats with record players on the floor.

I became obsessed with everything about them: their accents, their wit, their hair, especially their hair. Even today I can have deep conversations with like-minded types on what defines peak hair for The Beatles. My thoughts on this can change from one day to the next but widely speaking I put it somewhere between mid 1965 and early 1966 – from the making of Rubber Soul to the making of Revolver. Although, interestingly, I think Paul McCartney had a hair resurgence during the recording of the White Album. For Lennon, I think peak hair could be the Rubber Soul sleeve. George never stopped having great hair from 1963 to 1969.

David Bailey’s iconic 1965 portrait of Lennon & McCartney was both my photographic and musical ground zero. There are plenty of other great pictures of them but there’s nothing that comes as close to capturing that mid-sixties stylistic & monochromatic graphic austerity. Its insouciant directness, a one note symphony.

Now I am in London in late March 2003, a Friday, over from New York just for this one thing. I’m in the tenth year of my career as a photographer and I have been commissioned to photograph McCartney. All the way over on the plane, all the way here in the car, I keep reminding myself that this is one of the reasons why I became a photographer. To meet, spend time with, and document the people who define the era in which we live.

He’s got a world tour of arenas coming up so he’s rehearsing with his band in the now demolished London Arena. This is so they can all get the feel for an arena sized space. I have been told to arrive at 8am and set up in time to shoot McCartney at 10am.

The entire place has been set up as if for a show that is going to happen, but which never will. There’s lighting, full sound, catering for all the crew, even a wardrobe department which takes care of all Paul’s stage clothes and sartorial needs.

The arena floor is completely empty. There are no seats installed. It’s just a vast open space. We load all our gear in and build a full photographic studio right there on the floor in front of the stage. We are no more than twenty feet from stardom. I have been guaranteed half an hour with him.

10am comes and 10am goes. My assistants and I sit around for hours, mere yards from McCartney as he runs through song after song with his band, his entire live sound set-up being given the full workout. My own private show. It is a wonderful way to spend a day, doing nothing but watch Paul McCartney play the hits while I wait for him to give me half an hour in front of my camera. I die contented.

Finally, around 5pm I am told that he is ready and he comes over to my pop-up studio in the middle of the seatless auditorium. We are perhaps three minutes into it. I am barely even out of neutral and into first gear when he says, “Sorry, I’ve got to go…doing a live thing at the BBC. You’ve got enough, yeah?”

“But I was told we’d have half an hour.”

“I know but I just got behind on it all today and this BBC thing is live, so I’ve really gotta go. Anyway, you’ve got enough, haven’t you?”

Now or never.

“Well, not really, no, and to be honest I’m a bit disappointed. I came all the way over from New York for this. I was told to be here at 8am and ready at 10am, which I was. I sat here all day right in front of you and now you’re telling me you have to go.”

“You came from New York?“

“I live there.”

“New York, wow. Ok, fair enough. When are you going back?”

“Tuesday.”

“What are you doing on Monday?”

I shrugged an arms out, open palmed shrug, along with a pleading, yet hopeful face.

“Nothing.”

“Ok, I’ll tell you what, leave all your stuff here over the weekend. Our people will look after it. Come back on Monday and I’ll give you half an hour then.”

“Really? Half an hour?”

“Definitely, I promise.”

“Ok, thank you, that’s a deal.”

We shook hands on it and, as he gathered up his bag and coat, he told me about his first trip to New York in February 1964. The trip that kicked off American Beatlemania. Even now, he had not forgotten how utterly life changing the experience had been and he articulated the sense of awe that it instilled in them all, “Like…wowwwwwww!”

In the meantime, Paul’s car had been driven onto the arena floor and, as he climbed in the back, I had the pleasure of this brief exchange with one of the most famous people to have lived in the twentieth century:

“Bye then, Paul. Have a good weekend, I’ll see you Monday.”

“Yep, you too, see you Monday.”

All weekend, I realise that I have the advantage now. He’s bound himself to a commitment and promised me my half hour.

Come Monday, McCartney’s publicist is there to smooth things out. All is fine. Time is no problem but he’s not wearing the right clothes. I beg him to put on a dark round neck sweater and a dark grey pinstriped jacket on top of the white t-shirt he’s turned up in. He’s happy to oblige.

To give him an idea of what I have in mind, I mention my other favourite photographic series of The Beatles, after Bailey’s Lennon & McCartney session. It was four individual portraits, taken by Richard Avedon in August 1967, that he joined together as a single montage. Black and white, shot on a very dark background, all four of them in dark clothing, it is often referred to as the “Mount Rushmore” image. Paul struggles to remember but I describe it and he catches up. That, I explain, is my inspiration today.

How funny, I think, while he puts on the sweater. Something that to me, and millions of others, is the dictionary definition of iconic, yet the subject himself had to be reminded of it.

We go over to the studio set-up that has been in place since Friday. He’s in a good mood. Here is my theory. I’ve always had the sense that James Paul McCartney, throughout his life, has never stopped being an ambitious 1950s Liverpool grammar school boy. He’s competitive, focused, has a relentless work ethic, and likes to achieve something every day. His persona, his public persona, the one we all know, is a front that he has developed as a coping mechanism as the years have passed. I don’t think it’s a conscious front. It’s a part of him as much as his hands are a part of him. Underneath all that breezy, winsome charm is a surgical ruthlessness that has kept him and his interests aligned. It is this that I want to get on film.

Our half hour ticks by and I’m getting nothing different from what he’s given every other photographer for the last forty years. While I work, he chats a lot. It’s nice but it’s also distracting because he is almost unwilling to go where I want to lead him. In between these chatty moments he serves up a series of autopilot poses.

Inside, I’m losing altitude, I can see a plane just going down and down and down. The ground’s getting bigger in the window all the time when, finally, I just say it out loud:

“No, too much. Much too much. Do less. You’re an honest man, you can be sure of your achievements.”

“What’s the matter? You don’t like a bit of whimsy?”

Outside, the second Gulf War is only a few days old. I pause for a second, then understatedly say:

“Not when there’s a war on, Paul.”

And like that, it’s all there. The thin layer of sea covering the edge of the beach fizzles into the sand and everything I believed to be concealed underneath is revealed. The public McCartney we have known all our lives is gone, the eyes narrow and, the thing I remember most, his jawline tightens and clenches. For a few seconds his face has gone from soft marshmallow cherub to steel reinforced granite. Right there, for two frames, locked in silver nitrate, he hates me, and I love him for it.

Postscript

Not long after I took these portraits, I got a message that he was interested in buying the pictures outright. Copyright, negatives and all. My paranoid worry was that he disliked them enough to want them removed from the public domain, though whether that was the real reason or not, I will never know.

I thought about it for a while and then politely declined the offer, explaining that my rights in my photography were the equivalent to his publishing rights in his songs. Whatever you do, DO NOT give away your publishing. Besides, trade ownership of your work for a payment and once the money has gone, what do you have left?

A year or two on, back in London, I was cycling home from the West End one summer night, about 2am. I’d had a good evening and was merrily trundling along, enjoying the quiet melancholy of the deserted streets. I came through Regent’s Park, round Lord’s Cricket Ground, heading north. The streets were completely deserted, save for one couple on the pavement to my left up ahead as I turned right into Cavendish Avenue, where Paul has had a house since the mid-60s.

As I got closer, the slight upward incline making it a bit harder than it should have been, I sensed that the man seemed pleasantly inebriated, his arm around the woman, both consumed in each other’s company. As I drew almost level, I could hear his voice and realised who it was. I chugged past, standing up on my pedals and turning to clock them all in one move as I went.

He looked at me and in the most outrageous comedy Scouse accent, bellowed, “EY! GO EASY D’AIR LAD! KEEP YOUR EYES ON THE ROADDD WILL YA!”

The woman laughed and I nodded as I gave them both a little salute.

I continued on and at the end of Cavendish Avenue made the left turn into Circus Road, en route to a two wheeled, late-night glide across the Abbey Road zebra crossing, taking exactly the same journey that he has taken on foot to that studio a million times.

A thought drifted across the inside of my head:

“How about that? Paul McCartney will never, ever know that that guy on the bike was the photographer who turned down his offer to buy some pictures that he hates.”

Post-postscript

Twelve years later, I am contacted by someone at the publishers Hodder & Stoughton. They are publishing a collection of Paul du Noyer interviews with McCartney. Paul, it is believed, has interviewed Macca more than any other journalist, over a 35 year span. The book is to be called Conversations With McCartney and the man himself has the final say on the cover image. He would very much like to use one of my portraits of him from 2003.

Time, how mercurial she can be. Viewed through the prism of a twelve year gap, he had come to see those pictures as something special after all, which in its own way was the greatest reward of all.

Chris Floyd – This is an extract from Not Just Pictures (Reel Art Press) by Chris Floyd – From Book of the Week: Not Just Pictures | Idler

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.