Paul McCartney and Mal Evans spend some time in Los Angeles

April 10-11, 1967

Paul McCartney joins the board of the Monterey International Pop Festival

April 09 or 10, 1967

The Beatles’ brief stay in Beverly Hills

Aug 24, 1966

From Wikipedia:

Brian Douglas Wilson (born June 20, 1942) is an American musician, singer, songwriter, and record producer who co-founded the Beach Boys. Often called a genius for his novel approaches to pop composition, extraordinary musical aptitude, and mastery of recording techniques, he is widely acknowledged as one of the most innovative and significant songwriters of the 20th century. His best-known work is distinguished for its high production values, complex harmonies and orchestrations, layered vocals, and introspective or ingenuous themes. Wilson is also known for his formerly high-ranged singing and for his lifelong struggles with mental illness.

Raised in Hawthorne, California, Wilson’s formative influences included George Gershwin, the Four Freshmen, Phil Spector, and Burt Bacharach. In 1961, he began his professional career as a member of the Beach Boys, serving as the band’s songwriter, producer, co-lead vocalist, bassist, keyboardist, and de facto leader. After signing with Capitol Records in 1962, he became the first pop artist credited for writing, arranging, producing, and performing his own material. He also produced other acts, most notably the Honeys and American Spring. By the mid-1960s he had written or co-written more than two dozen U.S. Top 40 hits, including the number-ones “Surf City” (1963), “I Get Around” (1964), “Help Me, Rhonda” (1965), and “Good Vibrations” (1966). He is considered among the first music producer auteurs and the first rock producers to apply the studio as an instrument.

In 1964, Wilson had a nervous breakdown and resigned from regular concert touring, which led to more refined work, such as the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds and his first credited solo release, “Caroline, No” (both 1966), as well as the unfinished album Smile. As he declined professionally and psychologically in the late 1960s, his contributions to the band diminished, and legends grew around his lifestyle of seclusion, overeating, and drug abuse. His first comeback, divisive among fans, yielded the would-be solo effort The Beach Boys Love You (1977). In the 1980s he formed a controversial creative and business partnership with his psychologist, Eugene Landy, and relaunched his solo career with the album Brian Wilson (1988). Wilson disassociated from Landy in 1991 and went on to tour regularly as a solo artist from 1999 to 2022.

Heralding popular music’s recognition as an art form, Wilson’s accomplishments as a producer helped initiate an era of unprecedented creative autonomy for label-signed acts. The youth zeitgeist of the 1960s is commonly associated with his early songs, and he is regarded as an important figure to many music genres and movements, including the California sound, art pop, psychedelia, chamber pop, progressive music, punk, outsider, and sunshine pop. Since the 1980s, his influence has extended to styles such as post-punk, indie rock, emo, dream pop, Shibuya-kei, and chillwave. Wilson’s accolades include numerous industry awards, inductions into multiple music halls of fame, and entries on several “greatest of all time” critics’ rankings. His life was dramatized in the 2014 biopic Love & Mercy. […]

Paul McCartney and his wife Linda visited Wilson in April 1974, but Wilson refused to let them inside his home.

2000: Songwriters Hall of Fame, inducted by Paul McCartney,[765] who referred to him as “one of the great American geniuses”.[766]

Over the next year, Wilson continued sporadic recording sessions for his fourth solo album, Gettin’ In over My Head.[393] Released in June 2004, the record featured guest appearances from Van Dyke Parks, Paul McCartney, Eric Clapton, and Elton John.

Wilson’s cover of Paul McCartney’s “Wanderlust” was released on the tribute album The Art of McCartney in November.[436]

He praised Paul McCartney’s bass playing, calling it “technically fantastic, but his harmonies and the psychological thing he brings to the music comes through. Psychologically he is really strong […] The other thing that I could never get was how versatile he was. […] we would spend ages trying to work out where he got all those different types of songs from.”[512]

Paul McCartney and Brian had a mutual admiration for each other. Paul would come over to our house many times by himself, or with Linda and the kids. Paul came to the Vega-Tables session. Brian had some fresh vegetables out, for the mood. He sprinkled salt all over the console table near the mixing board and started dipping celery into the salt and chomping on it. Paul followed his lead and picked up the celery and did the same thing. It was priceless to see this.

Marilyn Wilson – first wife of Brian Wilson – From the liner notes of “The Smile Sessions (deluxe box”, Capitol Records, 2011

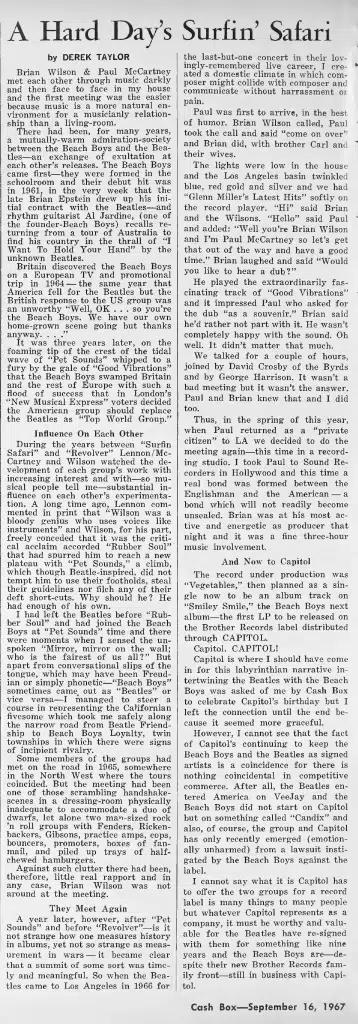

A Hard Day’s Surfin’ Safari

Brian Wilson & Paul McCartney met each other through music darkly and then face to face in my house and the first meeting was the easier because music is a more natural environment for a musicianly relationship than a living-room.

There had been, for many years, a mutually-warm admiration-society between the Beach Boys and the Beatles — an exchange of exultation at each other’s releases. The Beach Boys came first — they were formed in the schoolroom and their debut hit was in 1961, in the very week that the late Brian Epstein drew up his initial contract with the Beatles — and rhythm guitarist Al Jardine, (one of the founder-Beach Boys) recalls returning from a tour of Australia to find his country in the thrall of “I Want To Hold Your Hand” by the unknown Beatles.

Britain discovered the Beach Boys on a European TV and promotional trip in 1964 — the same year that America fell for the Beatles but the British response to the US group was an unworthy “Well, OK … so you’re the Beach Boys. We have our own home-grown scene going but thanks anyway…”

It was three years later, on the foaming tip of the crest of the tidal wave of “Pet Sounds” whipped to a fury by the gale of “Good Vibrations” that the Beach Boys swamped Britain and the rest of Europe with such a flood of success that in London’s “New Musical Express” voters decided the American group should replace the Beatles as “Top World Group.”

During the years between “Surfin Safari” and “Revolver” Lennon/McCartney and Wilson watched the development of each group’s work with increasing interest and with — so musical people tell me — substantial influence on each other’s experimentation. A long time ago, Lennon commented in print that “Wilson was a bloody genius who uses voices like instruments” and Wilson, for his part, freely conceded that it was the critical acclaim accorded “Rubber Soul” that had spurred him to reach a new plateau with “Pet Sounds,” a climb, which though Beatle-inspired, did not tempt him to use their footholds, steal their guidelines nor filch any of their deft short-cuts. Why should he? He had enough of his own.

I had left the Beatles before “Rubber Soul” and had joined the Beach Boys at “Pet Sounds” time and there were moments when I sensed the unspoken “Mirror, mirror on the wall; who is the fairest of us all?” But apart from conversational slips of the tongue, which may have been Freudian or simply phonetic — “Beach Boys” sometimes came, out as “Beatles” or vice versa — I managed to steer a course in representing the Californian fivesome which took me safely along the narrow road from Beatle Friendship to Beach Boys Loyalty, twin townships in which there were signs of incipient rivalry.

Some members of the groups had met on the road in 1965, somewhere in. the North West where the tours coincided. But the meeting had been one of those scrambling handshakescenes in a dressing-room physically inadequate to accommodate a duo of dwarfs, let alone two man-sized rock ’n roll groups with Fenders, Rickenbackers, Gibsons, practice amps, cops, bouncers, promoters, boxes of fanmail, and piled up trays of halfchewed hamburgers.

Against such clutter there had been, therefore, little real rapport and in any case, Brian Wilson was not around at the meeting.

A year later, however, after “Pet Sounds” and before “Revolver”—is it not strange how one measures history in albums, yet not so strange as measurement in wars — it became clear that a summit of some sort was timely and meaningful. So when the Beatles came to Los Angeles in 1966 for the last-but-one concert in their lovingly-remembered live career, I created a domestic climate in which composer might collide with composer and communicate without harrassment or pain.

Paul was first to arrive, in the best of humor. Brian Wilson called, Paul took the call and said “come on over” and Brian did, with brother Carl and their wives.

The lights were low in the house and the Los Angeles basin twinkled blue, red gold and silver and we had “Glenn Miller’s Latest Hits” softly on the record player. “Hi” said Brian and the Wilsons. “Hello” said Paul and added: “Well you’re Brian Wilson and I’m Paul McCartney so let’s get that out of the way and have a good time.” Brian laughed and said “Would you like to hear a dub?”

He played the extraordinarily fascinating track of “Good Vibrations” and it impressed Paul who asked for the dub “as a souvenir.” Brian said he’d rather not part with it. He wasn’t completely happy with the sound. Oh well. It didn’t matter that much.

We talked for a couple of hours, joined by David Crosby of the Byrds and by George Harrison. It wasn’t a bad meeting but it wasn’t the answer. Paul and Brian knew that and I did too.

Thus, in the spring of this year, when Paul returned as a “private citizen” to LA we decided to do the meeting again — this time in a recording studio. I took Paul to Sound Recorders in Hollywood and this time a real bond was formed between the Englishman and the American — a bond which will not readily become unsealed. Brian was at his most active and energetic as producer that night and it was a fine three-hour music involvement.

The record under production was “Vegetables,” then planned as a single now to be an album track on “Smiley Smile,” the Beach Boys next album — the first LP to be released on the Brother Records label distributed through CAPITOL.

Capitol. CAPITOL!

Capitol is where I should have come in for this labyrinthian narrative intertwining the Beatles with the Beach Boys was asked of me by Cash Box to celebrate Capitol’s birthday but I left the connection until the end because it seemed more graceful.

However, I cannot see that the fact of Capitol’s continuing to keep the Beach Boys and the Beatles as signed artists is a coincidence for there is nothing coincidental in competitive commerce. After all, the Beatles entered America on VeeJay and the Beach Boys did not start on Capitol but on something called “Candix” and also, of course, the group and Capitol has only recently emerged (emotionally unharmed) from a lawsuit instigated by the Beach Boys against the label.

I cannot say what it is Capitol has to offer the two groups for a record label is many things to many people but whatever Capitol represents as a company, it must be worthy and valuable for the Beatles have re-signed with them for something like nine years and the Beach Boys are — despite their new Brother Records family front — still in business with Capitol.

Derek Taylor – From Cashbox – September 16, 1967

Officially appears on Gettin' In Over My Head

Unreleased song

Unreleased song

"Vega-Tables" session with The Beach Boys

Apr 10, 1967

By Brian Wilson • Official album

Party At The Palace : The Queen's Concerts, Buckingham Palace

By Various Artists • Official album

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.