September 1-23, 1973

"Band On The Run" sessions in Lagos

Last updated on December 28, 2025

September 1-23, 1973

Last updated on December 28, 2025

Previous session May 14, 1973 • Mixing "Zoo Gang"

Interview Aug 11, 1973 • Denny Laine interview for Record Mirror

Article Aug 29, 1973 • Henry McCullough and Denny Seiwell quit Wings

Session September 1-23, 1973 • "Band On The Run" sessions in Lagos

Session October 1973 • "Band On The Run" sessions #2

AlbumSome of the songs worked on during this session were first released on the "Band On The Run (UK version)" Official album

We were there for three weeks and we recorded seven tracks. We didn’t use anyone. We ended up working with just the three of us. We did the whole thing with just the three of us.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles: Off The Record 2 – The Dream is Over: Dream Is Over Vol 2” from Keith Badman

I thought it’d be good to get out of the country to record, so I asked EMI where they had studios round the world. There were some amazing countries where they had studios and I thought ‘Lagos… Africa… rhythms… yeah’, cause I’ve always liked African music

Paul McCartney, from Club Sandwich N°47/48, Spring 1988

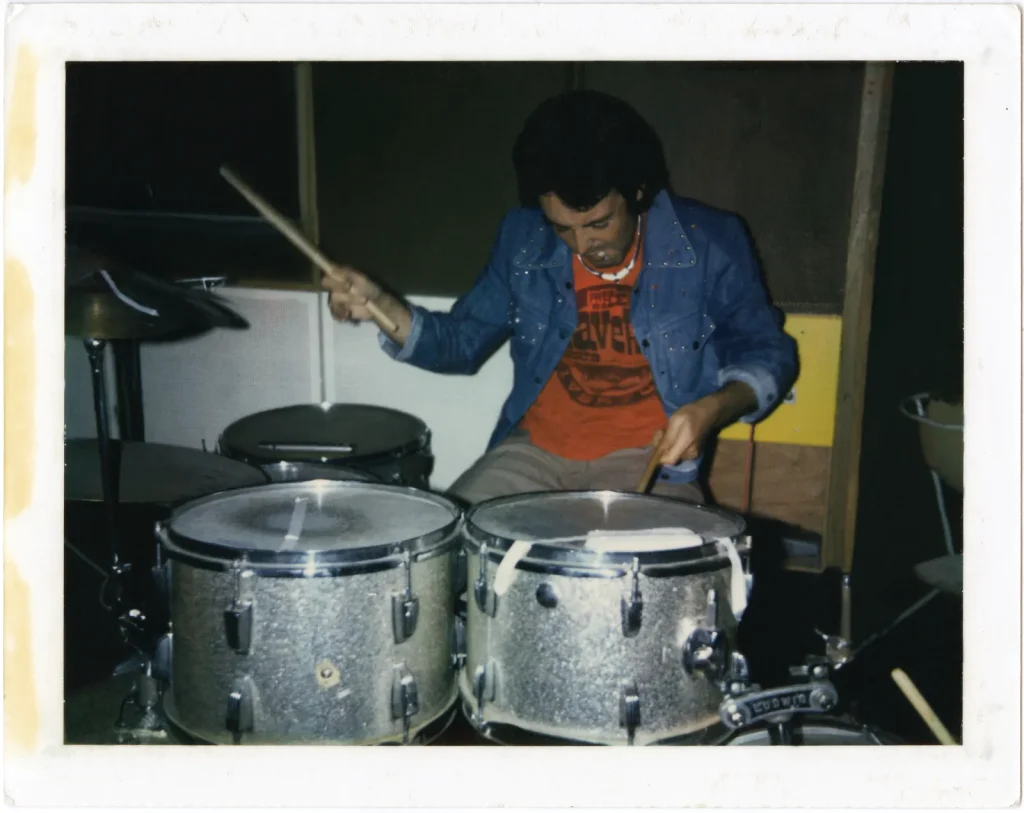

The idea to go to Lagos was originally just to have some fun because I didn’t fancy recording in London. I fancied getting out and EMI have got studios all over the world, including one in communist China, but because that was so far away, we decided to go to Lagos, because it would be sunny and warm. Then when we got there, we thought, ‘What are we going to do?’ So I played drums, Linda played piano and mellotron, Denny Laine added some extra guitar parts and between us we managed to make the sound a bit fuller. They were even building the studio when we got there.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles: Off The Record 2 – The Dream is Over: Dream Is Over Vol 2” from Keith Badman

We thought that it would be warm and sunny out in Africa. We thought it would be like a fab holiday place but it’s not the kind of place you’d go for a holiday. It’s warm and tropical but it’s the kind of place you’d have monsoons. We caught the end of the rainy season and there were tropical storms all the time. There were power cuts, too and loads of insects. It does bother some people but we’re not creepy-crawly freaks. Linda doesn’t mind lizards. But someone else, for instance the engineer we took out, who did Sgt. Pepper and Abbey Road, he couldn’t stand them. So a couple of the lads put a spider in his bed. It was all a bit like scout camp. The worst a lizard can do is bite you. So we’re not freaked out by that, not like Ringo’s wife, Maureen, who can’t even stand a fly in her room. If one comes near her, she freaks out.

Over there, they don’t have many swimming pools and stuff, just a couple of big ones because they’re frightened of malaria. What’s more, we went there intending to use some of the local musicians. We thought we might have some African brass and drums and things. We started off thinking of doing a track with an African feel, or maybe a few tracks, or maybe even the whole album, using the local conga players and African fellows. But when we got there, and we were looking round and watching the local bands, one of the fellows, Fela Ransome Kuti, came up to us after a day or two, and said, ‘You’re trying to steal the black musicians’ music.’ We said, ‘No we’re not! Do us a favour, Fela. We do all right as it is, actually. We sell a record here and there. We just want to use some of your guys.’ But he got heavy about it, until in the end we thought, ‘Blow you then, we’ll do it all ourselves.’ So we did and the only guy from Africa we used, Remi Kebaka, was someone we met in London, then we discovered that he came from Lagos. But that was purely coincidental.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles: Off The Record 2 – The Dream is Over: Dream Is Over Vol 2” from Keith Badman

It was a lot of misunderstanding. We met Fela through Ginger Baker, who has a studio over there, and one night we went down to The Shrine, a club that Fela has. Anyway, he used to come by the studios and it was all very friendly and then one day, he came by with a lot of heavies and sort of sat Paul down and said, ‘You’re stealing our music.’ And Paul said, ‘I’m not. Come and listen to the tracks. I haven’t used any of your musicians.’ The trouble was, Hugh Masekela went there and used an African band and they did the same thing to them, you know, ‘You’re going to take our music and exploit it.’ Hugh said no and he did.

Linda McCartney – From “The Beatles: Off The Record 2 – The Dream is Over: Dream Is Over Vol 2” from Keith Badman

Then, after we had been in Lagos a couple of weeks, we were held up and robbed at knife point. Linda and I had set off like a couple of tourists, loaded with tapes and cameras, to walk to Denny’s house, which was about twenty minutes down the road. A car pulls up beside us and goes a little bit ahead. Then a guy gets out and I thought that he wanted to give us a lift. So I said, ‘Listen, mate, it’s very nice of you, thanks very much, but we are going for a walk.’ I patted him on the back and he got back in the car, which went a little way up the road. It stopped again and Linda was getting a bit worried. Then one of them, there were about five or six black guys, rolled down the window and asked, ‘Are you a traveller?’ I still think that if I had thought really quickly and said, ‘Yes, God’s traveller,’ or something like that to freak them out a bit, maybe they would have left us alone. But I said, ‘No, we are just out for a little walk. It’s a holiday and we are tourists,’ giving the whole game away. So, with that, all the doors of the car flew open and they all came out and one of them had a knife. Their eyes were wild and Linda was screaming, ‘He’s a musician, don’t kill him,’ you know, all the unreasonable stuff you shout in situations like that. So I’m saying, ‘What do you want? Money?’ And they said, ‘Yeah, money,’ and I handed some over. Shaking, we walked on home and we were just sitting down having a cup of coffee to try and recover our nerves and there was a power cut. We thought they had come back and cut the power cables. We had a lot of trouble sleeping that night and got back to the studio the next day to be told, ‘You’re lucky to be alive. If you had been black, they’d have killed you. But, as you’re white, they know you won’t recognise them.’ I wanted to call the police, but everyone said it would do no good there at all. With that we had to carry on and make the record, adding to the pressure, which we had already got. It seemed stuffy in the studio, so I went outside for a breath of fresh air. If anything, the air was more foul outside than in. It was then that I began to feel really terrible and had a pain across the right side of my chest and I collapsed. I could not breathe and so I collapsed and fainted. Linda thought I had died.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles: Off The Record 2 – The Dream is Over: Dream Is Over Vol 2” from Keith Badman

I laid him on the ground and his eyes were closed and I thought he was dead!

Linda McCartney – From “The Beatles: Off The Record 2 – The Dream is Over: Dream Is Over Vol 2” from Keith Badman

The doctor seemed to treat it pretty lightly and said it could be bronchial because I had been smoking too much. But this was me in hell. I stayed in bed for a few days, thinking I was nearly dying. It was one of the most frightening periods in my life. The climate, the tensions of making a record, which had just got to succeed, and being in this totally uncivilised part of the world finally got to me…

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles: Off The Record 2 – The Dream is Over: Dream Is Over Vol 2” from Keith Badman

I thought Lagos was going to be gorgeous but I’d overlooked the realities of going to somewhere like that — the studio wasn’t built properly and it was like monsoon season. Again, though, out of adversity came something good.

Paul McCartney – From “Wingspan: Paul McCartney’s Band on the Run“, 2002

One night me and Linda got mugged. We’d been told not to walk around, but in those days we were slighly hippie – ‘Hey, don’t worry’. About five fellers jumped out of a car and one of them had a knife, so all my tapes went. These were all the songs I’d written, so I had to try and remember them all. The joke is, I’m sure the fellers who took them wouldn’t know what they were. They probably chucked them away, so lying in some Nigerian jungle there’s little cassettes of Band On The Run.

Paul McCartney, from Club Sandwich N°47/48, Spring 1988

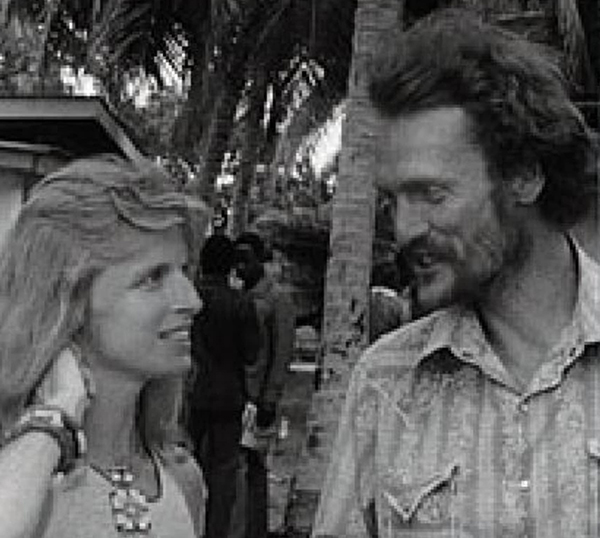

Paul was signed to EMI. He picked somewhere on the map where they had a studio. And of course, we loved all that music. They weren’t up-to-date exactly with the equipment, but we didn’t need it. We got more out of just being there and being influenced by all that music, which was fantastic. Ginger being there was great for me, because I felt more at home because I had a friend in the same town. We did go over to Ginger’s one day just as a courtesy. Ginger put some sounds [on the session], if you like. He… actually played a fire bucket full of gravel for a shaker sound.

Denny Laine – From From the Moody Blues to Wings to the Rock Hall: Q&A with Denny Laine | Ideastream Public Media, February 15, 2023

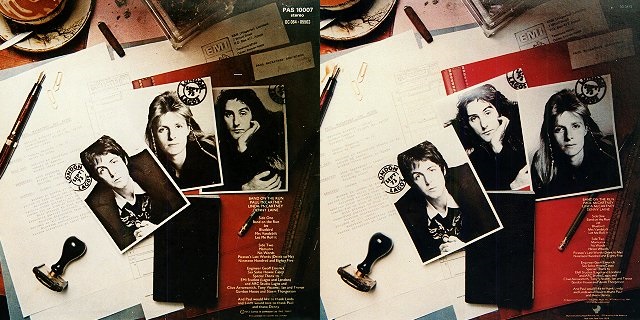

Going back to “Band on the Run,” on the back cover there’s little passport photos of Paul, then Linda, then you. On the American album, they’re reversed and you’re the one closest to Paul. Did you ever notice that? Is there some hidden meaning there?

No way! I don’t know. You experiment with the photographer, just like everything else. It’s like the guy who did the “Band on the Run” front cover, he had the wrong film in his camera! It turned out that it was sepia-toned. The color was just, like, weird because it wouldn’t have been that way with the right film. Then I think it was Paul or Linda [who] said, “We like the color.” And he went, “Oh, thank you,” [from] a mistake. A lot of things happen like that. You just make the most of it.

Denny Laine – From From the Moody Blues to Wings to the Rock Hall: Q&A with Denny Laine | Ideastream Public Media, February 15, 2023

For Band on the Run, what did you think when Paul and Linda decided to go to Lagos?

“I thought it was a great idea. I love going places where we’re going to be influenced by the local culture and music. Also, Ginger Baker had a studio there. We didn’t go there for that reason, but Ginger introduced us to some people, so we didn’t feel so alone [Note: Baker played percussion on Mamunia, shaking gravel in an old fire bucket]. The African drumming thing was a big influence on all of us.

“We were all into ethnic music, whether reggae or African or whatever. We sat around and looked at the map where all the EMI studios were and picked that one. ‘That sounds like it could be fun.’ Also, I think it might’ve been the only location available for when we wanted to go. I never had any negative feelings about going. I thought it was a nice change. There was a great energy there. Though we didn’t know it would be monsoon season. [Laughs]”

Denny Laine – From Guitar World, January 30, 2023

What was the studio like in Lagos?

“They didn’t have anything. It was all hand-me-down equipment. Half of it wasn’t even rigged up. There was a door in the back that opened up into a record-pressing plant, with, like, 60 people working away. As for the equipment, obviously we’d brought our own guitars and amps. Again, like on Red Rose Speedway, I was using the Telecaster and the Gibson Jumbo.”

Denny Laine – From Guitar World, January 30, 2023

In order to move forward, you have to try new things. It’s like being a gambler. You gamble with things because it’s more exciting. It’s more appealing. It’s not the normal, everyday 9-to-5 job, it’s more of a ‘Let’s try something new.’

Denny Laine – From ‘Band on the Run’: Denny Laine on McCartney’s ‘Gamble’ of an Album – Billboard, May 2023

I know why [Band On The Run] was appreciated so much. Because it had a certain feel. It was basically just me and Paul doing the backing tracks. And it was more of a relaxed approach to doing an album than if you’re going in with a band and there are all these parts. We were thrown into that as a last resort because two of the guys didn’t come to Lagos.

Denny Laine – From ‘Band on the Run’: Denny Laine on McCartney’s ‘Gamble’ of an Album – Billboard, May 2023

When [Paul] said, ‘Let’s do it in Africa,’ I understood completely. We wanted to go somewhere where it was different. We’d be influenced by the music and the atmosphere, and it was far away from anything else we’d ever done. Because it was an EMI studio, I think they just put a pin in the map and said, ‘How about Africa?’ I just went: ‘Great, let’s do it.’

Denny Laine – From ‘Band on the Run’: Denny Laine on McCartney’s ‘Gamble’ of an Album – Billboard, May 2023

Because of his fame, of course, I was in the shadows more, but I wasn’t bothered by that at the time. I was traveling the world and learning a lot and having a good time in many ways. So from that point of view, it was easy for me. I’m very adaptable. When I’m around people who are not adaptable, I get a little bit nervous.

Denny Laine – From ‘Band on the Run’: Denny Laine on McCartney’s ‘Gamble’ of an Album – Billboard, May 2023

Me and Paul, we had the same influences musically and had known each other since the ’60s. It was just easy. It was easy to get a good groove on each other’s songs, and I think that’s what made the album popular.

We did it almost as though it was a home recording. A lot of the equipment that was out there really wasn’t workable. It was all hand-me-downs from EMI, and they really didn’t know what they were doing. And we kept it basic. No frills.

Normally, me and him would get together somewhere and write together — before we go in the studio. He’d come up with an idea, or I would, and then it would be a co-written thing. Or he would have written the songs and I would have known them before we go into the studio because we’d rehearsed them together. That’s what I really enjoyed about [Band on the Run]: the fact we were thrown in the deep end, and we had to swim, and we came up with that feel that we always had anyway.

Denny Laine – From ‘Band on the Run’: Denny Laine on McCartney’s ‘Gamble’ of an Album – Billboard, May 2023

It was just the three of us, and the input I had makes it stand out as something special. Me and him had this kind of feel together musically. We slotted in well together. We could read each other, and that came from growing up on the same musical influences. Paul’s got a good sense of rhythm, and he doesn’t overplay, which I like.

Denny Laine – Interview January 2023 – From Facebook

Lagos was an unconventional choice. The capital of Nigeria, it was once a part of the British Empire, but had been independent since 1960. A sprawling city, it was dealing with a host of problems, including some ongoing difficulties from Nigeria’s recent civil war (and hundreds of thousands of refugees). But it hosted a dynamic local music scene, personified by the flamboyant Fela Ransome-Kuti (as he was then known), who hosted nightly revels in his club, the Afrika Shrine. Another English musician, Ginger Baker—formerly the drummer with Cream—had resettled in Lagos after building a studio of his own, ARC, the first sixteen-track recording studio on the continent.

Paul McCartney: So we ended up in Lagos, which was . . . interesting. It wasn’t the sort of paradise we thought it would be, but it didn’t matter, because we were basically spending a lot of time in the studio.

The rhythms of Africa interest me. They do interesting things that are kind of jazzy, but not what you might call jazzy. They’ll do things like setting a 3/4 rhythm against a 4/4 rhythm—I think it’s called ‘polymetric’. I love that. You’ll hear that a lot in African music.

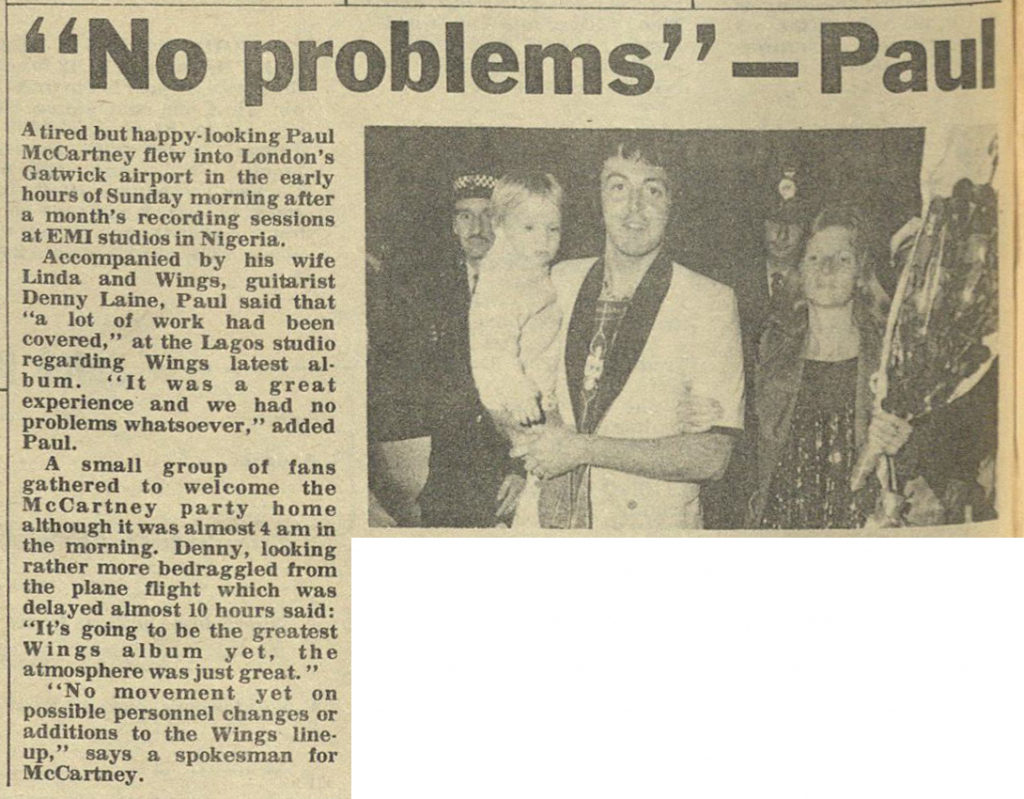

Paul and Linda flew from Gatwick Airport to Lagos on August 31, 1973, along with their children and Denny Laine. They had not realized that September marked the beginning of the monsoon season, which increased the risk of public health problems in a city that was already desperately in need of sanitation, water and medical supplies. Nigeria was still reeling from the three-year civil war (1967–1970) over Biafra, a region in the eastern part of the country that had unsuccessfully sought independence. As many as one million Biafrans may have died in the conflict (mostly from starvation), but Nigeria remained intact with international support, including assistance from the UK. When John Lennon returned his MBE medal to the Queen in November 1969, it was partly, he said, “as a protest against Britain’s involvement in the Nigeria–Biafra thing.”

Since the end of the war, many thousands of refugees had settled in the shantytowns of Lagos. They received little help from the military strongman who led Nigeria, President Yakubu Gowon. A local report on housing and sanitation declared that Lagos had “virtually become unlivable.”

Geoff Emerick, recording engineer: To my horror, when I rang the consulate I was informed that I was required to first pay a visit to London’s Tropical Disease Hospital in order to have yellow fever, typhoid and cholera shots. As he jabbed me in the arm with the painful vaccines, the doctor also casually mentioned that I’d have to take malaria tablets the whole time I was there. I actually got a mild dose of yellow fever as a result of the vaccinations—much like a bad flu—and it lasted for about five days. This was already starting to seem like a really bad idea.

Denny Laine, Wings guitarist: It was kind of scary at Lagos. It was just after a war and everything and everybody wanted to sell you something or get you to employ them to get them out of the country. So, to us, it was a little bit awe-inspiring. But at the same time, they were very nice people to us, welcoming. And we felt at home. You have that certain freedom when you’re in a situation where you’re being invited to be a part of their world. But at the same time, they’re learning from us. And we invited them into our world, which was good for them.

Paul McCartney: They were building Lagos when we got there. It was before oil—now it’s a big city, but they were just building it. It was like mud huts, a couple of BOAC buildings, a pool you had to stick lots of chlorine in, all very dodgy.

It was monsoon season, pissing down with rain, so it wasn’t even sunny most of the time. That song “Mamunia”—“Rain comes…”—was the vibe. And they were building the studio when we got there.

The recording sessions were a constant challenge, with unreliable equipment. Some of these setbacks might have crippled a less determined band. But they persevered.

Paul McCartney: Everyone was freaked out. Geoff Emerick freaked because he hated spiders. So the road crew put a spider in his bed. It was buggy too. Everywhere was like an airport lounge—bare, never any furniture anywhere, and fluorescent strip lighting with millions of bugs around it. I hated it. It’s really not my idea of comfort, but I didn’t hate it as much as Geoff did. It totally freaked him.

Geoff Emerick: I have no love for lizards or snakes or insects. Never have, probably never will. Unfortunately, those are three things that Nigeria has in abundance, which probably tempered my view of what I am sure is an otherwise lovely country. By the second day I was there, I hated the place.

It actually all started the day I arrived. I wandered into the kitchen to have a poke around, just to see if the cupboards were stocked with anything edible. I opened the door to the pantry and nearly jumped out of my skin: somebody had stored their collection of dead spiders there. . . . When I went to sleep that night and pulled the covers back, I found that Denny had discovered the collection as well and had put several of the dead spiders in my bed. . . .

The next morning, I woke from a deep, refreshing sleep, and in the warmth of the sun everything seemed a lot brighter. “This place isn’t so bad,” I was thinking, as I gazed out the bedroom window. At least the villa was gorgeous, the company tolerable, the impending project full of promise. Just then, this huge lizard popped up from the tall grass, staring right at me. It had a big, red head and a green neck… it was terrifying! I didn’t know what to think. Then I began looking around the bedroom and realised that I was sharing my space with a family of translucent ‘jelly lizards’, scuttling all over the walls, ceilings and floors. One night in that villa was quite enough for me.

Paul McCartney: It wasn’t at all like Abbey Road. We said, “Where’s the vocal booth?” And they said, “Oh, we don’t have one.” We said, “Oh, you don’t have a vocal booth? Okay.” They were so nice, these two engineers. One was called Monday and the other one was called Innocent. They were so great, and yes, very innocent. So we had to show them a few studio tricks.

We said, “Well, look, we’ll get some wood, we’ll build a big box, and if you get some Perspex that you can look through, we’ll put that in the box, and then seal it so, and have a little door.” So we taught them how to make a vocal booth.

Geoff Emerick: The EMI studio in Lagos was really small, without any sort of acoustic screens, which we had to have made. There was no drum booth, the microphone supply was a cardboard box just full of old mics, and there were half of the amplifiers missing in the eight-track tape machine. And there was a door at the back of the studio—I’ll always remember this—it was a soundproof door, and you open this door, and at the back of the studio was the pressing plant, where they pressed all the records. And there was, like, fifty or sixty people stamping out records at the back of the studio. That’s one thing that has stuck in my mind.

Denny Laine: You could smell all the Bakelite from the records—the making of the actual records. I remember that smell. And then going in and, ‘Uh-oh, what have we got here?’

A lot of the [studio] gear was, shall we say, antique. Hand-me-down is what it was, a lot of that stuff from EMI Studios. And they didn’t even know how to use it. So we went in there and rigged up what we needed, which was basically a tape machine. But we had a great engineer, Geoff Emerick. So we got it done.

It was [Paul] playing drums and me playing something live. And then, if we needed to add things later, we’d make up a click track maybe so that we could put other stuff to it. We’d experiment. Then it would fit.

Paul McCartney: It was quite a joy being so slimmed-down. And the things that made that record difficult to make? Well, they’re some of the things that make that record great.

One serious setback occurred when Paul and Linda were mugged while walking down a street in Lagos. The thieves took a notebook of lyrics as well as the demo tapes Paul had been working from. As a result, he had to recreate all of the songs from memory. In some ways, it was a blessing to be in such a small band, able to improvise quickly.

Paul McCartney: Six guys leapt out of a car. We’d been told not to walk anywhere; they’d said, “This is Africa, man, just don’t walk, take a car everywhere.” But, you know, that’s what they say in Harlem, and you’ve got to experience the place. So, me and Linda were walking half an hour from a mate’s place to our bungalow. It was a beautiful night—cameras, tape recorders all over us, prime mugging targets. And this car pulled up, Linda got a bit apprehensive, the window came down.

I said, “Hello.” “Are you travellers?” I said, “Er, yeah, we’re just walking, you know, just walking along here.” So the car went on for a few yards, and then it stopped again. They’d obviously had a discussion, and one of them got out. I said, “Eh, listen, mate, it’s very nice of you to offer us a lift, but it’s okay, we’re walking.” They were gonna mug us! And me, soft head, you know, is going, “That’s a really nice offer, man. You don’t get many people who’d offer a lift like that. Go on. Fine. Off you go, get back in.” And I pushed him back in the car! Another discussion, another few yards. Next time, they’d discussed this thoroughly—all the doors opened, six people jumped out. The little one had a knife, he was shaking, he was shitting himself, and so was I at this point. I’d suddenly realized what this was.

And Linda is a ballsy chick, she’s screaming, “Don’t touch him! He’s a musician. He’s just like you. He’s a soul brother, leave him alone!” She’s screaming at the top of her voice. “Come on. What do you want, man? Money? Here. You can have it. The tape? Sure! Take it. Camera? Yeah, go on, you can have it all. Go on.”

They left. And they actually turned round and came back. We thought we’d dive into the bushes, but luckily they took another turn and screamed off in the car. I said, “Right, we walk fast, very fast, and don’t stop for anything.” Forced march. Got back to the villa. The minute we got back, cup of tea…all the lights went out. It turned out to be a power cut, but I said, “They’ve followed us. They’re gonna do us.” You know how you think. It’s not rational. And you know what we did? I said, “Let’s go to bed.” That was the best we could think of. We couldn’t ring anyone, there was no police, no guards or nothing. We just went to bed, pulled the bedclothes over us and stayed there till morning. Praying that morning would come. And it did. But I was a nervous wreck.

So they took our tapes. Back then, you’d write a song and record it on cassette. But the good thing was that by making those demo recordings, it helped me remember them so we could still piece them back together and make the record. When I started writing songs, I didn’t have anything to record them on, so you’d have to just use your memory. If the song was any good, you’d remember it. So, luckily, those muscles had been flexed before. Our joke was that we thought they probably erased and recorded something “good” over them.

We got to the studio the next day, and the guy who owned the studio says, “You’re lucky you’re white; they would have killed you if you’d been Black, because they’d have figured you would have recognized them. But knowing you’re white, they know you won’t recognize them. You got off with your lives there.”

There was another setback when Paul collapsed outside the studio, gasping for air, unable to speak.

Paul McCartney: Linda thought I’d died. I just fainted one night. But I never faint. So then I just remember being driven through these crazy marketplaces. It was scary. Going to the hospital in the back of a taxi through this hub of the city of Lagos, and it’s night, all noise and chaos, hardly able to take a breath. And I’m lying there, thinking, “Bloody hell! Is this where I’m going to die?” So we get to the hospital and it turned out to be a bronchial spasm. I’d just been smoking too much. Scary, but easy to fix. They gave me something for it and I lived to sing another day.

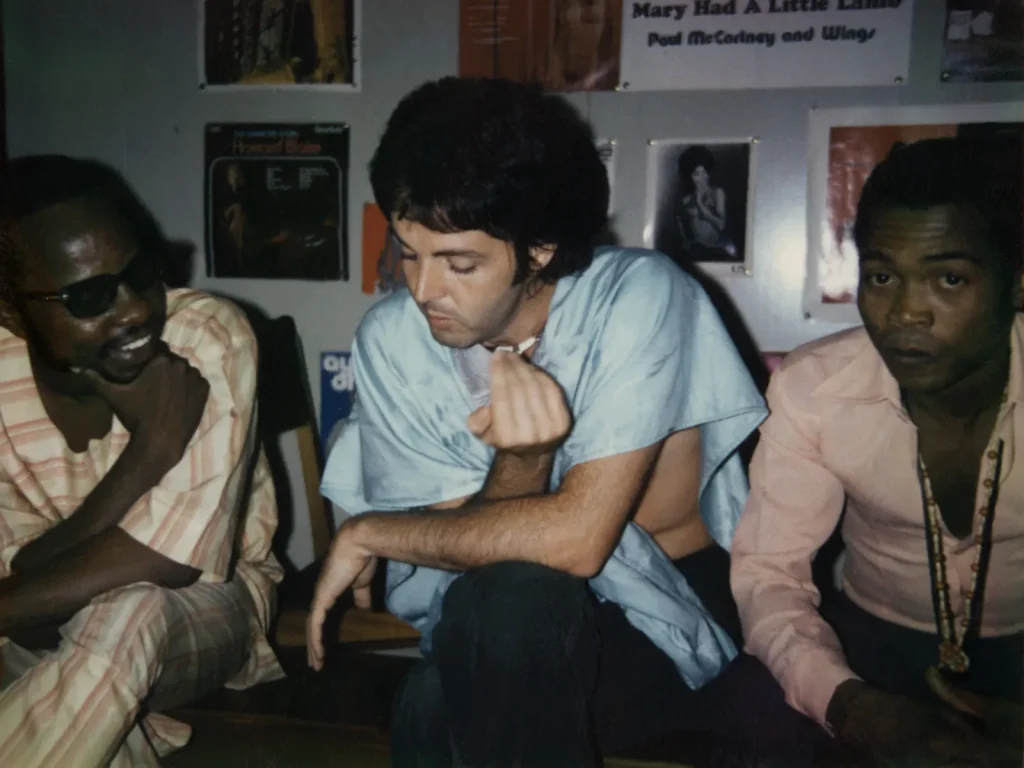

When we got to Lagos and were trying to set up the studio, one of the first things that came out was this front-page story in a local newspaper with “Paul McCartney of The Beatles comes to Lagos.” It quoted Fela Ransome-Kuti, as he was called then, saying, “He’s come to steal the Black man’s music. He’s come to do this and all that.” And it hurt me.

I thought, “No, that’s not what I’ve come for. I’ve come for rhythm, the inspiration of being around that music.” Like being in Jamaica, hearing a lot of reggae. So I thought, “Well, what can I do?” I rang Ginger [Baker] and said, “Hey, man, this has gone down and I’d like to try and talk to Fela.” And Fela came round to the EMI studio with…it had to be thirty people.

Fela came into the control room while the rest of the entourage stayed in the studio, and we had a chat. “Hey man, you know, listen, I’ve not come here to steal your music. And it saddens me that you think that. Let me play you something that we’ve been recording.” I said, “The nearest thing we’ve got is this thing ‘Mamunia.’” I said, “Let me play it to you.”

So he listened and kinda liked it. And he said, “It’s not like Nigerian music.” He realized that we weren’t stealing his music, and we became really good friends.

They’d seen it happen before, where people would come to Lagos, be friendly, then go home and have hits with their style of music. So I think they were a little paranoid. They were frightened of that happening again. “This is our music. If there’s any money to be made, we must make it.” I knew he was right about that.

Fela invited us to his place, the Afrika Shrine, which is now a legendary venue. It was out of Lagos somewhere in a big tent. A tent with slats in it. There was no real roof. And it was great. So we went there and got stoned. Fela’s grass was very strong.

So all of us were like—and me in particular, although I can only really speak for myself—I was, like, tripping. It was like, “Oh, God, what’s going on here?” And I got very paranoid. Fela was bringing people for us to meet, and I was seeing them as, like, the figure of death. It was trippy. They were perfectly nice people, I found out later. But with me in this state, it was very scary.

Fela gave us these seats at the side of the stage. And they said these are the best seats in the house. We said, “We don’t want the best seats.” We’re just trying to be nice and not the pushy whites. Then he started the music, and it was unbelievable. I’d never heard anything like it in my life. I’d heard African music on record, but I’d never been in a room with it. And this band, I mean, I can still remember the lineup of the band. Incredible.

Fela was in the front on a little Farfisa keyboard. And he’s looking out to the crowd, singing out the front. He’s got his band behind him. Well, they kicked in this rhythm, and I could do nothing but weep. It just hit me so hard. It was like, boom, and I’ve never heard anything as good, ever, before or since. I mean, I’ve heard lots of fabulous music. I’ve heard Hendrix live and some great, great stuff, but this was the killer. And, like I say, tears just pouring down my cheeks. It’s just so good. It just hit me.

I can still remember the riff, and the saxes come in. This beautiful noise, and the conga players and the guitar players, then the percussion guys just standing up at the front. Fela is center stage, topless, with, like, a grass skirt on. He’s like the chief of the tribe. He’s playing the keyboard. And to either side of him were percussionists. One of them, a very long, tall, lanky guy in black-and-white-striped trousers, is just throwing around this little percussion instrument, and like he’s just playing with it. Just tossing it in the air and stuff, like it’s a little kid’s toy. The other side is another percussionist. Right at the back, there were two conga players, and they are like the rhythm machine. Nowadays, it would be a rhythm box.

So you got those two guys in the back. And then, either side of them, you have the sax players, four or six sax players—a big baritone and all the various types of saxes. Then there’s a drummer over to the right-hand side, and only because he’s got all this percussion going, he can afford to do what I would call “lead drums.” He can just accentuate bits. He’s commenting on the music. It’s like lead drumming. Fantastic.

Then there’s the guitars, and they had a tenor guitar and a kind of bass guitar. Sort of a little African guitar. It’s just so lovely. And then you had dancers. I think most of which were his wives. And they’re all topless on the dance floor in front of him with the grass skirts. An unbelievable vision. And just when the whole thing kicked in, I cried. I couldn’t imagine any other reaction.

Denny Laine: It was just a great night. They were all stoned out of their heads and they were all dancing. It was very hot, all that kind of thing. And Fela was like the prince. And he had his Africa 70 [band], they were called. It was like a big band thing. They’d love to just get out there and just shake it all down. So as soon as we saw that and were part of it, we felt at home.

Despite the challenges, the recording sessions continued efficiently, revealing the strength of the songs that had been written prior to the trip. On September 22, 1973, the band flew back to London. Work continued on the songs at George Martin’s AIR Studios, with ongoing overdubs and orchestration by Tony Visconti.

Geoff Emerick: We did actually manage to record all the basic rhythm tracks and overdub all that onto eight-track within four and a half weeks.

Paul McCartney: After our crazy adventure in Africa, we returned home to London to open a letter from EMI that had been sitting there just before we left. It read, “Len Wood, Chairman of EMI: Dear Paul, I understand you’re taking your family to our Lagos studios. Would advise against your going as there’s just been an outbreak of cholera.” Thanks for the warning!

Excerpted from Wings: The Story of a Band on the Run by Paul McCartney, available November 4, 2025. Reprinted with the permission of W.W. Norton & Company and the author.

From Paul McCartney Gets Mugged, Stoned, Hospitalized, and Inspired in Lagos, Nigeria | GQ

Written by Paul McCartney, Linda Eastman / McCartney

Recording

Written by Paul McCartney, Linda Eastman / McCartney

Recording

Written by Paul McCartney, Linda Eastman / McCartney

Recording

Written by Paul McCartney, Linda Eastman / McCartney

Recording

Written by Paul McCartney, Linda Eastman / McCartney

Recording

Written by Paul McCartney, Linda Eastman / McCartney

Recording

Picasso's Last Words (Drink To Me)

Written by Paul McCartney, Linda Eastman / McCartney

Recording

Paul McCartney: Music Is Ideas. The Stories Behind the Songs (Vol. 1) 1970-1989

With 25 albums of pop music, 5 of classical – a total of around 500 songs – released over the course of more than half a century, Paul McCartney's career, on his own and with Wings, boasts an incredible catalogue that's always striving to free itself from the shadow of The Beatles. The stories behind the songs, demos and studio recordings, unreleased tracks, recording dates, musicians, live performances and tours, covers, events: Music Is Ideas Volume 1 traces McCartney's post-Beatles output from 1970 to 1989 in the form of 346 song sheets, filled with details of the recordings and stories behind the sessions. Accompanied by photos, and drawing on interviews and contemporary reviews, this reference book draws the portrait of a musical craftsman who has elevated popular song to an art-form.

The McCartney Legacy: Volume 1: 1969 – 73

In this first of a groundbreaking multivolume set, THE MCCARTNEY LEGACY, VOL 1: 1969-73 captures the life of Paul McCartney in the years immediately following the dissolution of the Beatles, a period in which McCartney recreated himself as both a man and a musician. Informed by hundreds of interviews, extensive ground up research, and thousands of never-before-seen documents THE MCCARTNEY LEGACY, VOL 1 is an in depth, revealing exploration of McCartney’s creative and personal lives beyond the Beatles.

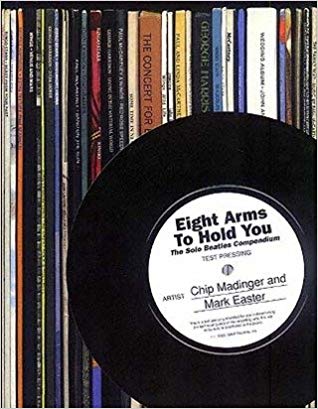

Eight Arms to Hold You: The Solo Beatles Compendium

Eight Arms To Hold You: The Solo Beatles Compendium is the ultimate look at the careers of John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr beyond the Beatles. Every aspect of their professional careers as solo artists is explored, from recording sessions, record releases and tours, to television, film and music videos, including everything in between. From their early film soundtrack work to the officially released retrospectives, all solo efforts by the four men are exhaustively examined.

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.