Wednesday, June 1, 1966

Recording "Yellow Submarine"

For The Beatles

Last updated on November 17, 2023

Wednesday, June 1, 1966

For The Beatles

Last updated on November 17, 2023

April 6 - June 22, 1966 • Songs recorded during this session appear on Revolver (UK Mono)

Recording studio: EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Previous session May 26, 1966 • Recording "Yellow Submarine"

Article June - July 1966 ? • Designing the "Revolver" cover

Article June 1966 • George Harrison and Paul McCartney meet Ravi Shankar

Session Jun 01, 1966 • Recording "Yellow Submarine"

Interview June 1966 • The Beatles interview for The Beatles Monthly Book

Session Jun 02, 1966 • Recording "I Want To Tell You", mixing "Yellow Submarine"

Some of the songs worked on during this session were first released on the "Revolver (UK Mono)" LP.

This was the 24th day of the recording sessions for the “Revolver” album.

The Beatles recorded the basic track of “Yellow Submarine” and the first vocal overdubs on May 26, 1966. On this day, during a 12-hour long session (from 2:30 pm to 2:30 am), The Beatles completed the track by adding sound effects and backing vocals onto take 5, with a little help from their friends and a brass band.

From Wikipedia:

Sound effects overdub

The Beatles dedicated their 1 June session to adding the song’s sound effects. For this, Martin drew on his experience as a producer of comedy records for Beyond the Fringe and members of the Goons. The band invited guests to participate, including Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones, Harrison’s wife Pattie Boyd, Marianne Faithfull, Beatles road managers Mal Evans and Neil Aspinall, and Alf Bicknell, the band’s driver. The studio store cupboard was sourced for items such as chains, bells, whistles, hooters, a tin bath and a cash till.

Although effects were added throughout the track, they were heavily edited for the released recording. The sound of ocean waves enters at the start of the second verse and continues through the first chorus. Harrison created this effect by swirling water around a bathtub. On the third verse, a party atmosphere was evoked through a combination of Jones clinking glasses together and blowing an ocarina, snatches of excited chatter, Boyd’s high-pitched shrieks, Bicknell rattling chains, and tumbling coins. To fill the two-bar gap following the line “And the band begins to play”, Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick used a recording of a brass band from EMI’s tape library. They disguised the piece by splicing up the taped copy and rearranging the melody.

The recording includes a sound-effects solo over the non-singing verse, designed to convey the submarine’s operation. Lennon blew through a straw into a pan of water to create a bubbling effect. Other sounds imitate the whirring of machinery, a ship’s bell, hatches being slammed, chains hitting metal, and finally the submarine submerging. Lennon used the studio’s echo chamber to shout out commands and responses such as “Full speed ahead, Mr Boatswain.” From a hallway just outside the studio, Starr yelled: “Cut the cable!” Gould describes the section as a “Goonish concerto” consisting of sound effects “drawn from the collective unconscious of a generation of schoolboys raised on films about the War Beneath the Seas”. According to Echard, the effects are “an especially rich example of how sound effects can function topically” in psychedelia, since they serve a storytelling role and further the song’s “naval and oceanic” narrative and its nostalgic qualities. The latter, he says, is “due to their timbre, recalling radio broadcasts not only as a contemporary experience but also as an emblem of the near-distant past”, and he also sees the effects as cinematic in their presentation as “a coherent sonic scenario, one that could be diegetic to an imagined series of filmic events”.

In the final verse, Lennon echoes Starr’s lead vocal, delivering the lines in a manner that musicologist Walter Everett terms “manic”. Keen to sound as if he were singing underwater, Lennon tried recording the part with a microphone encased in a condom and, at Emerick’s suggestion, submerged inside a bottle filled with water. This proved ineffective, and Lennon instead sang with the microphone plugged into a Vox guitar amplifier.

All the participants and available studio staff sang the closing choruses, augmenting the vocals recorded by the Beatles on 26 May. Evans also played a marching bass drum over this section. When the overdubs were finished, Evans led everybody in a line around the studio doing the conga dance while banging on the drum strapped to his chest. Martin later told Alan Smith of the NME that the band “loved every minute” of the session and that it was “more like the things I’ve done with the Goons and Peter Sellers” than a typical Beatles recording. Music critic Tim Riley characterises “Yellow Submarine” as “one big Spike Jones charade”.

Discarded intro

The song originally opened with a 30-second section containing narration by Starr and dialogue by Harrison, McCartney and Lennon, supported by the sound of marching feet (created by blocks of coal being shaken inside a box). Written by Lennon, the narrative focused on people marching from Land’s End to John o’ Groats, and “from Stepney to Utrecht”, and sharing the vision of a yellow submarine. Despite the time taken in developing and recording this intro, the band chose to discard the idea, and the section was cut from the track on 3 June. Everett comments that the recording of “Yellow Submarine” took twice as much studio time as the band’s debut album, Please Please Me.

It must have been one of the most unusual Beatles sessions ever. It was more like the things I’ve done with The Goons and Peter Sellers. The boys loved every minute of it. We needed all kinds of sound effects, and sandbags were bumped about while John blew bubbles and George made swirling sounds with the water. I think it worked out very well. There was also a brass band. This wasn’t a sound effect on tape, the band was right there in the studio, not to mention a massed chorus made up of anybody and everybody who happened to be around at the time. This means that you don’t just hear Ringo and the other Beatles singing ‘Yellow Submarine’, you also hear Patti Harrison, studio staff, sound engineers and The Beatles’ faithful road managers Mal and Neil. Incidentally, John isn’t speaking through a bottle when he repeats Ringo’s words in the song. This original idea didn’t work out, so Mal Evans evolved an ingenious method by which the words were spoken by John through his guitar amplifier.

George Martin – From “The Beatles: Off The Record” by Keith Badman, 2008 – From a 1996 interview with New Musical Express ?

Most of that afternoon was spent trying to record a spoken word introduction to “Yellow Submarine.” Back in 1960, there had been a well publicized charity walk by a doctor named Barbara Moore from Land’s End to John O’Groats — the two points farthest apart on the British mainland. John, who often had his head buried in a newspaper when he wasn’t playing guitar or singing, had written a short medieval-sounding poem that somehow tied the walk to the song title, and he was determined to have Ringo recite it, accompanied by the sound of marching feet. I pulled out the old radio trick of shaking coal in a cardboard box to simulate footsteps, and Ringo did his best to emote, deadpan, but the final result was, in a word, boring. Even though we spent hours and hours putting it together, the whole idea was eventually scrapped. Nearly thirty years later, we did tack the introduction back on to the remixed version of “Yellow Submarine” that was included on the B-side of the CD single “Real Love,” one of two Lennon songs completed posthumously by the surviving Beatles and released in 1996.

Paul had conceived “Yellow Submarine” as a singalong, and so a few of the band’s friends and significant others had been invited along for the evening’s session. By then, everyone was distinctly in a party mood. Though we hadn’t tried pot ourselves, Phil and I had been around enough musicians to know what it was, and we were sometimes aware of the funny smell in the studio after the Beatles and their roadies snuck a joint off in the corner, though I doubt very much if the straightlaced George Martin knew what was going on. Like guilty kids, Mal or Neil would sometimes try to cover the odor by lighting incense, but that in itself was a tip-off to us. We didn’t say anything, though: if the Beatles wanted to get high during their recording sessions, it was none of our business. We were there to do a job, and we just carried on with the work at hand.

Following a long dinner break (during which we suspected more than food was being ingested), a raucous group began filtering in, including Mick Jagger and Brian Jones, along with Jagger’s girlfriend Marianne Faithfull and George Harrison’s wife, Patti. They were all dressed in their finest Carnaby Street outfits, the women in miniskirts and flowing blouses, the men in purple bell-bottoms and fur jackets. Phil and I put up a few ambient microphones around the studio, and I decided to also give everyone a handheld mic on a long lead so they could move around freely — there was no way I was going to try to contain that lot! The two Rolling Stones and Marianne Faithfull basically acted as if I didn’t exist; to them, I guess I was just one of the invisible “little people.” Patti was more gracious, going out of her way to say hello to me. She seemed shy but also very charming.

The whole marijuana-influenced scene that evening was completely zany, straight out of a Marx Brothers movie. The entire EMI collection of percussion instruments and sound effects boxes were strewn all over the studio, with people grabbing bells and whistles and gongs at random. To simulate the sound of a submarine submerging, John grabbed a straw and began blowing bubbles into a glass — fortunately, I was able to move a mic nearby in time to record it for posterity. […]

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

People began clinking wineglasses and shouting out at random; those background screams during the second verse came from Patti Harrison, which was always ironic to me, considering how quiet she usually was. At one point, I had to run out to the studio to see where everyone had disappeared to; I could hear voices coming over the control room speakers but I couldn’t see anyone. It turned out the party had relocated into the small echo chamber at the back of the room. As I opened the door, I again detected the faint smell of “incense.” As we neared midnight, Mal Evans began marching around the studio wearing a huge bass drum on his chest, everyone else in line behind him conga-style singing along to the chorus. It was utter madness.

When John ran back into the echo chamber and ad-libbed his “Captain, captain” routine to the sound of clanking bells and chains, we were all doubled over with laughter. The ambience around his voice was just perfect, and that was the way that all those bits happened. Although the record sounds quite produced, it was actually spur of the moment—John and the others were just out there having a good time. Somehow it worked, though, despite the chaos.

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

There was a metal bath in the trap room, the type people used to bathe in in front of the fire. We filled it with water, got some old chains and swirled them around. It worked really well. I’m sure no one listening to the song realised what was making the noise.

John Skinner – From The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions by Mark Lewisohn, 2004

On ‘Yellow Submarine’, I was bashing chains in a bucket of water for sound effects and shuffling sand.

Mal Evans – From “The Beatles: Off The Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

If George Martin clearly remembers that a brass band was brought in (Mark Lewisohn confirms as well), Geoff Emerick clearly states that pre-recorded tapes were used:

Throughout the day, George Martin and I had been overdubbing various nautical sounds from sound effects records in the EMI library. That same library was to be put to good use later that night, when it came time to add a solo to the song. By then, everyone was too knackered — or stoned — to give much attention to the two-bar gap that had been left for a solo, and with the enormous amount of time that had already been spent on the track, George Martin wasn’t about to begin the long process of having George Harrison strap on a guitar and laboriously come up with a part. Instead, someone — probably Paul — came up with the idea of using a brass band. There was, of course, no way that a band could be booked to come in on such short notice, and in any event, George Martin probably wouldn’t have allocated budget to hire them, not for such a short section. So instead, he came up with an ingenious solution — one that, with the passage of time, he has apparently forgotten. […]

Phil McDonald was duly dispatched to fetch some records of Sousa marches, and after auditioning several of them, George Martin and Paul finally identified one that was suitable—it was in the same key as “Yellow Submarine” and seemed to fit well enough. The problem here was one of copyright; in British law, if you used more than a few seconds of a recording on a commercial release, you had to get permission from the song’s publisher and then pay a negotiable royalty.

George wasn’t about to do either, so he told me to record the section on a clean piece of two-track tape and then chop it into pieces, toss the pieces into the air, and splice them back together. The end result should have been random, but, somehow, when I pieced it back together, it came back nearly the same way it had been in the first place! No one could believe their ears; we were all thoroughly amazed. But by this point, it was very late at night and we were running out of time—and patience—so George had me simply swap over two of the pieces and we flew it into the multitrack master, being careful to fade it out quickly. That’s why the solo is so brief, and that’s why it sounds almost musical, but not quite. At least it’s unrecognizable enough that EMI was never sued by the original copyright holder of the song.

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

“Yellow Submarine” would be mixed in mono on June 3, 1966, and in stereo on June 22.

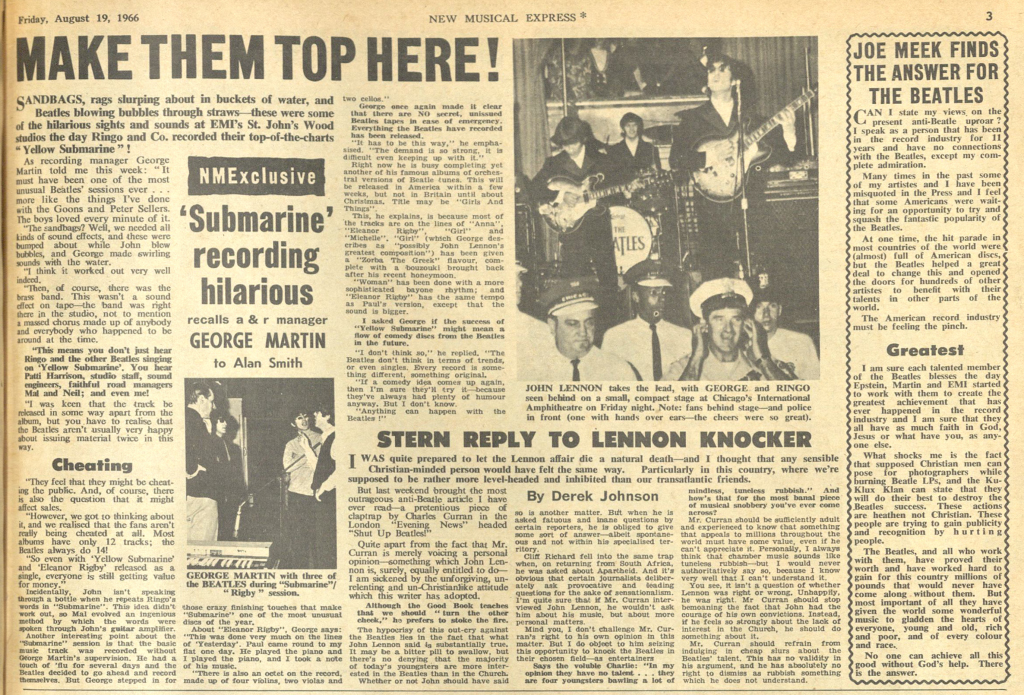

‘SUBMARINE’ RECORDING HILARIOUS

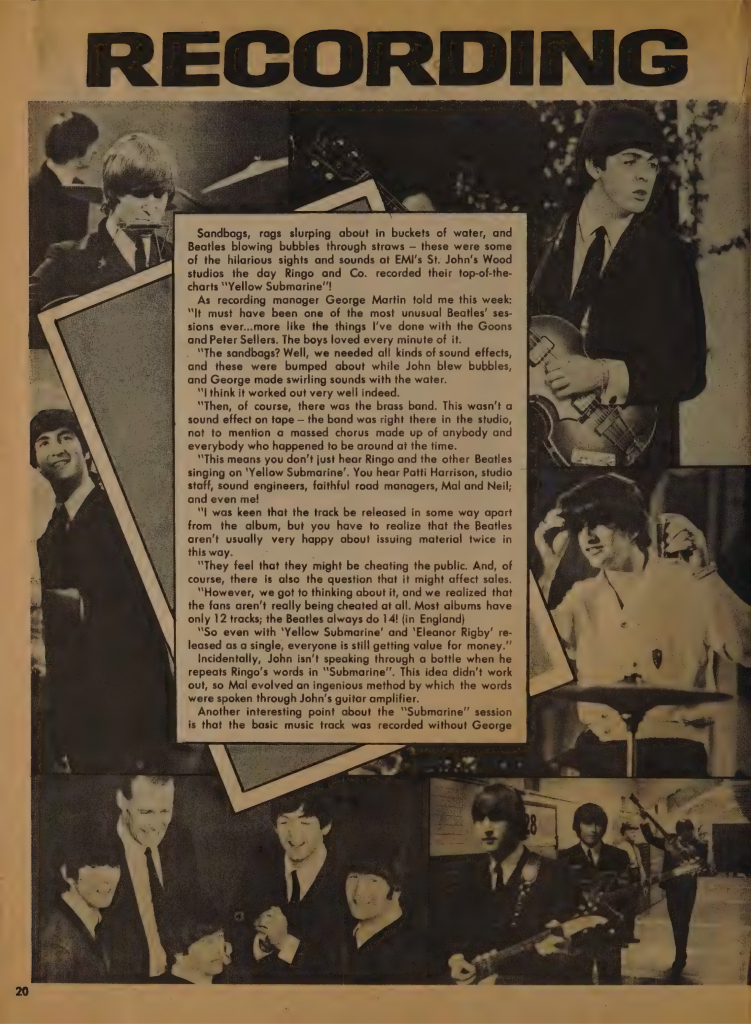

Sandbags, rags slurping about in buckets of water, and Beatles blowing bubbles through straws – these were some of the hilarious sights and sounds at EMI’s St. John’s Wood studios the day Ringo and Co. recorded their top-of-the-charts “Yellow Submarine”!

As recording manager George Martin told me this week: “It must have been one of the most unusual Beatles’ sessions ever… more like the things I’ve done with the Goons and Peter Sellers. The boys loved every minute of it.

“The sandbags? Well, we needed all kinds of sound effects, and these were bumped about while John blew bubbles, and George made swirling sounds with the water. I think it worked out very well indeed. Then, of course, there was the brass band. This wasn’t a sound effect on tape – the band was right there in the studio, not to mention a massed chorus made up of anybody and everybody who happened to be around at the time. This means you don’t just hear Ringo and the other Beatles singing on ’Yellow Submarine’. You hear Patti Harrison, studio staff, sound engineers, faithful road managers, Mal and Neil; and even me!

“I was keen that the track be released in some way apart from the album, but you have to realize that the Beatles aren’t usually very happy about issuing material twice in this way. They feel that they might be cheating the public. And, of course, there is also the question that it might affect sales. However, we got to thinking about it, and we realized that the fans aren’t really being cheated at all. Most albums have only 12 tracks; the Beatles always do 14! (in England). So even with ’Yellow Submarine’ and ’Eleanor Rigby’ released as a single, everyone is still getting value for money.”

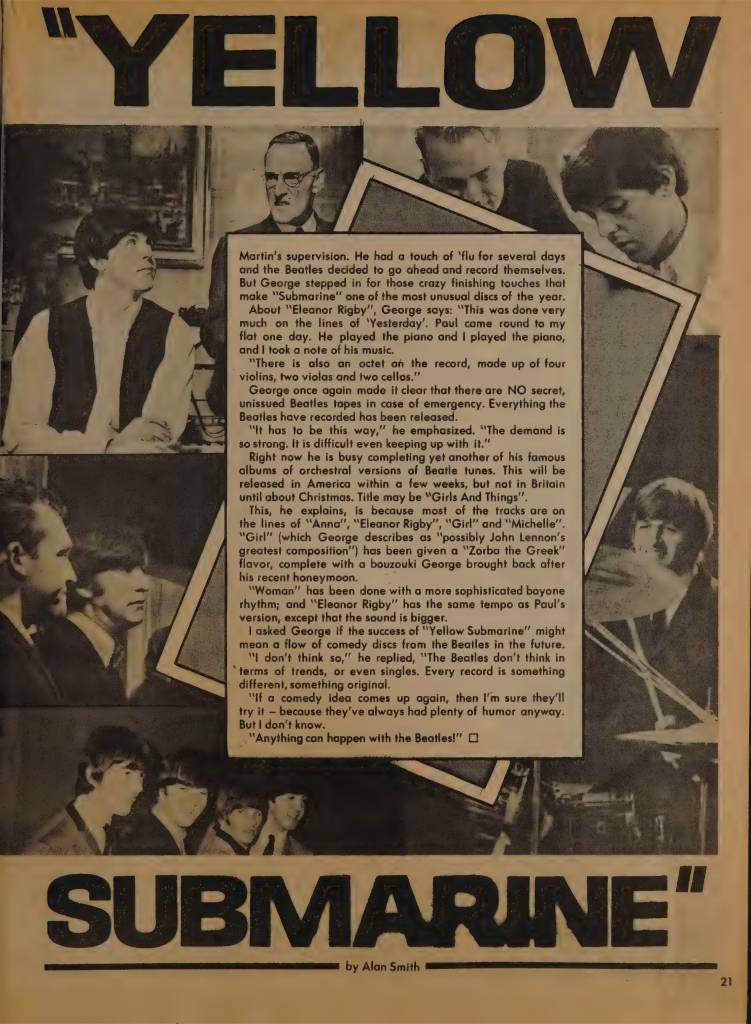

Incidentally, John isn’t speaking through a bottle when he repeats Ringo’s words in “Submarine”. This idea didn’t work out, so Mal evolved an ingenious method by which the words were spoken through John’s guitar amplifier. Another interesting point about the “Submarine” session is that the basic music track was recorded without George Martin’s supervision. He had a touch of flu for several days and the Beatles decided to go ahead and record themselves. But George stepped in for those crazy finishing touches that make “Submarine” one of the most unusual discs of the year.

About “Eleanor Rigby”, George says: “This was done very much on the lines of ‘Yesterday’. Paul came round to my flat one day. He played the piano and I played the piano, and I took a note of his music. There is also an octet oh the record, made up of four violins, two violas and two cellos.”

George once again made it clear that there are NO secret, unissued Beatles tapes in case of emergency. Everything the Beatles have recorded has been released.

“It has to be this way,” he emphasized. “The demand is so strong. It is difficult even keeping up with it.”

Right now he is busy completing yet another of his famous albums of orchestral versions of Beatle tunes. This will be released in America within a few weeks, but not in Britain until about Christmas. Title may be “Girls And Things“. This, he explains, is because most of the tracks are on the lines of “Anna”, “Eleanor Rigby”, “Girl” and “Michelle”. “Girl” (which George describes as “possibly John Lennon’s greatest composition”) has been given a “Zorba the Greek” flavor, complete with a bouzouki George brought back after his recent honeymoon.

“Woman” has been done with a more sophisticated bayone rhythm; and “Eleanor Rigby” has the same tempo as Paul’s version, except that the sound is bigger.

I asked George if the success of “Yellow Submarine” might mean a flow of comedy discs from the Beatles in the future.

“I don’t think so,” he replied, “The Beatles don’t think in terms of trends, or even singles. Every record is something different, something original. If a comedy idea comes up again, then I’m sure they’ll try it – because they’ve always had plenty of humor anyway. But I don’t know. Anything can happen with the Beatles!“

From New Musical Express – August 19, 1966

Recording • Spoken word introduction to “Yellow Submarine”

AlbumOfficially released on Real Love

Recording • SI onto take 5

The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions • Mark Lewisohn

The definitive guide for every Beatles recording sessions from 1962 to 1970.

We owe a lot to Mark Lewisohn for the creation of those session pages, but you really have to buy this book to get all the details - the number of takes for each song, who contributed what, a description of the context and how each session went, various photographies... And an introductory interview with Paul McCartney!

The Beatles Recording Reference Manual - Volume 2 - Help! through Revolver (1965-1966)

The second book of the Association for Recorded Sound Collections (ARSC)-nominated series, "The Beatles Recording Reference Manual: Volume 2: Help! through Revolver (1965-1966)" follows the evolution of the band from the end of Beatlemania with "Help!" through the introspection of "Rubber Soul" up to the sonic revolution of "Revolver". From the first take to the final remix, discover the making of the greatest recordings of all time.

Through extensive, fully-documented research, these books fill an important gap left by all other Beatles books published to date and provide a unique view into the recordings of the world's most successful pop music act.

If we modestly consider the Paul McCartney Project to be the premier online resource for all things Paul McCartney, it is undeniable that The Beatles Bible stands as the definitive online site dedicated to the Beatles. While there is some overlap in content between the two sites, they differ significantly in their approach.

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.