Wednesday, November 23, 1966

Interview for Punch Magazine

The Pop Guru

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Last updated on November 6, 2023

Wednesday, November 23, 1966

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Last updated on November 6, 2023

Previous interview November 1966 • The Beatles interview for The Beatles Monthly Book

Article Nov 19, 1966 • The Beatles resign from The Beatles Ltd

Article Nov 22, 1966 • Paul McCartney and John Lennon visit the Robert Fraser Gallery

Interview Nov 23, 1966 • Paul McCartney interview for Punch Magazine

Article Nov 24, 1966 • The Beatles attend an exhibition by Greek sculptor Takis Vasilakis

Session Nov 24, 1966 • Recording "Strawberry Fields Forever" #1

Next interview December 1966 • The Beatles interview for The Beatles Monthly Book

Officially appears on Revolver (UK Mono)

Officially appears on Revolver (UK Mono)

Paul McCartney reviews Paul Simon

August 1973 • From Punch Magazine

This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

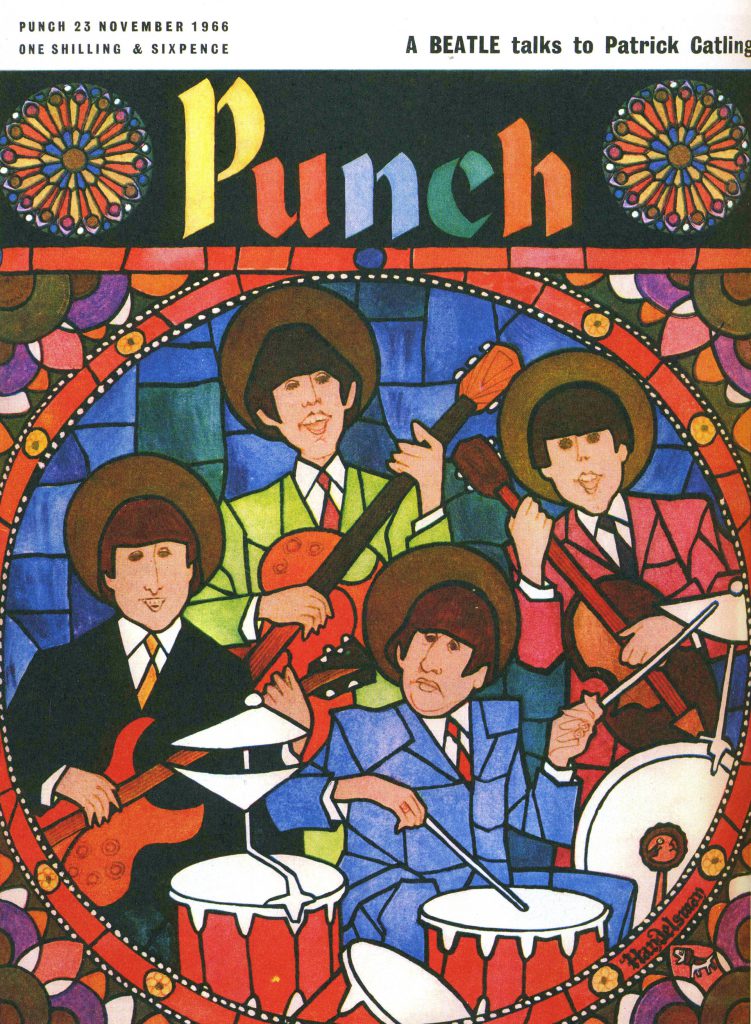

Would the Beatles’ music last if the Group split up? PATRICK SKENE CATLING talks to Paul McCartney about the Lennon / McCartney sound

“‘THIS YELLOW SUBMARINE,’ they say. ‘Why yellow? Why a submarine? What does it symbolise?'”

Paul McCartney, resting in his comfortable Victorian mansion in an electrically locked high-walled compound in St. John’s Wood, was patiently discussing the present state of the Beatles and their songs, which, in my opinion, is entirely admirable, enviable even, but difficult. So much has been achieved; so much is expected.

It is difficult, for example, when their public, the whole world, subjects their lightest, most casual utterance, musical or conver-sational, to searching critical analysis. What were the socioeconomic, political, psychological and religious implications of a yellow submarine? Did the disc jockeys approve? Did the Board of Trade? Did the Navy? Did God?

Whatever the complexity of the commercial considerations of Brian Epstein and Nems Enterprises, Ltd., and of course they are vast, intricate and far-reaching, the songs themselves seem to have been conceived and brought forth in the pure, simple spirit of mystical innocence, like paintings by Chagall — and perhaps somewhat less like the philosophical happenings staged by Dr. Timothy Leary. The songs are honest, direct, imaginative, original, unique, and intimately universal.

A yellow submarine just is. Children readily understand, and so do gurus entranced by the sound of one hand clapping. There is something about that frivolously gaudy, escapist, anti-authoritarian, unwarlike warship that appeals to almost everybody, in my own small private world, Mr. Hathaway, a Gloucestershire gardener in his sixties, sings “Yellow Submarine” as he prunes the roses, in a voice neither worse nor very much better than Ringo’s; when the official recording is played, my one-year-old daughter seizes a hi-fi speaker with both hands and rocks herself and it in perfect non-verbal sympathy.

“The idea was just to do a children’s song,” McCartney said, smiling calmly though perhaps a tiny bit peeved by people who insist on elaborate interpretations. “But there is a yellow submarine place, it’s real even if it is only a hallucination.”

Hallucinations have a reality and a genuine importance of their own. They can be powerfully persuasive. The idea obviously fascinates him and the others, and it has begun to show, in a carefully controlled way, in some of their music, most notably in the Lennon-McCartney composition “Tomorrow Never Knows.” To hallucinate, to wander in the mind, to perceive experience beyond the senses, may sombrely suggest morbid delusions. Positively, on the other hand, it represents total mobility and absolute freedom. No matter how far the rockets fly, the only way out of the world is inwards. The mind, and only the mind, can encompass the universe.

Saints have achieved hallucinosis by starving and scourging themselves and by hypnotically repetitiously praying. Madison Avenue executives have achieved it less successfully with vodka martinis and slogans. A distinguished London anaesthesiologist has told me that mescalin and certain other non-addictive hallucinatory drugs are as safe and as dangerous as one’s own existing psychic tendencies, an assurance that makes me want to try them, a warning that makes me dare not. The Beatles now provide an encouraging musical nudge in the direction of infinite personal liberation. Pop goes the ego. The sensation is not at all unpleasant. I think that Bernard Handelsman’s cover this week is profoundly significant.

I choose to detect a similar message in Klaus Voormann’s brilliant sleeve design, partly pen-and-ink drawing, partly photographic collage, for the Beatles’ latest LP, “Revolver.” It shows them on a dream safari through the jungle tendrils of their own famous hair. “Revolver” revolves, making one as dizzy as a whirling dervish, and in the blood-red daze appears a glint of happy enlightenment.

“Turn off your mind, relax and float down-stream,” the lyric of “Tomorrow Never Knows” urges you. “It is not dying…” In a letter to McCartney, Kenneth Tynan, the critic and Literary Manager of The National Theatre, has called the song, as the Beatles perform it, “the best musical evocation of LSD I’ve ever heard.’’ Judging it by the testimony of a friend who used the drug under medical supervision, I feel sure that Tynan’s reaction was justified.

The Beatles were not the first musicians to write a song of this sort. Murray Grand, a sensitive and witty New York lyricist who used to write in an urbanely Cole Porterish style, wrote a song called “Long Sweet Dream,” with music by Ralph Burns. But the Beatles carried the idea farther forward, using impressionistically exotic sounds, the uncanny buzzing drone of a tambura, a four-stringed Indian instrument that looks like a bloated outsize wooden barometer, the heavy blurred thump and hard rattle of drums, the moaning and honking of reeds, the Orientally nasal chanting of John Lennon’s voice filtered and distorted by an unimaginably cunning microphone. The music comes and goes in mysterious, vertiginous waves, creating a frightening but thrilling sense of warped space and time, like a supernatural unconscious vision in an operating theatre.

“When we wrote it,” McCartney said, “John had just read Leary’s book on psychedelic experience, a manual based on the Tibetan book of the dead. To us it was just great. It’s difficult to speak the truth, but there are these people around, the great people who speak the truth. Some of them are bums. It’d be nice to meet Leary before he’s God.”

But if they did meet him, McCartney acknowledged fatalistically, no doubt there would be an international outcry of protests that the Beatles were now taking drugs.

“Once we’ve done a song it goes out and that’s it.” he said. “We don’t want to argue about it. We don’t feel as though we’re answerable. If you don’t like our kind of thing don’t listen. The good thing is that actually we started out with the assumption that we’d never talk down. We hated people in gold lame suits. You can get caught up in the whole machine of it all and turn into Paul Getty in the end. Nothing but money. We like commercialism, but it can be something else as well. What we’ve always wanted to do is do what we want to do. At twenty-four I’m very lucky that I can do what I want. A lot of people expect us to live up to our Beatle mop-top image. But we’ve changed. We either had to adapt and try new things or else go potty.”

Accustomed to the round cherubic softness in early pictures of McCartney, I adjusted to recognition that he has changed visibly. The face today is leaner and firmer and more mature. There was really no need for the anarchic experimental moustache that he grew on last month’s holiday.

The Beatles have come a long way since 1955, when Lennon, a fifth-former at Quarry Bank High School in Liverpool, acquired an old guitar and formed a skiffle and rock ‘n’ roll group called The Quarrymen. McCartney joined the group that summer, George Harrison joined three years later, and Ringo Starr joined them as The Beatles in 1962.

“We had a lousy limiting range and we got fed up with it,” McCartney said.

He was expressing himself unduly harshly, perhaps, but it is true that nowadays some of the first records, “Love Me Do,” “Please Please Me,” “From Me To You” and “She Loves You,” sound primitively crude in comparison with recent inventions. But the enthusiasm, energy and imagination were overwhelming right from the beginning. Other musicians were quick to appreciate The Beatles. Ella Fitzgerald, after recording their song “Can’t Buy Me Love,” said: “Paul and John are perhaps even better as writers than you think. This song has almost a blues sequence in it. The words are good, but the jazz sequence is a gas — and that’s not even counting the beat.”

The more they succeed, the freer they feel to attempt daring innovations, the more they succeed. Rivals and imitators are repeatedly made to look flat-footed, ham-fisted, slow-witted, embarrassed and dull. Now they’re desperately trying to get that Indian sound.

McCartney enjoys playing with sounds. He has made tape-recordings of weird “space noises” and “electronic music” reminiscent of some of the stuff produced by the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop. He once set up a line of tumblers containing different amounts of water to record the sounds made by wet fingers rubbing around the rims. He has made multi-track tapes of himself singing, playing the piano, lead guitar, bass and drums.

“But we don’t care so much about just pure sound,” he said. “We like notes.”

At the same time, Lennon’s words have gone far beyond the conventional limited scope of pop songs. After the fragmentary adolescent journal, “The Daily Howl,” after the dark thoughts of loneliness and insecurity expressed in the Joycean punning fables of “In His Own Write” and “The Spaniard in The Works,” he now seems to be confident enough, and certainly he is able, to write sermons and diatribes as well as today’s best love songs. There’s nobody else anywhere writing songs like “Dr. Robert,” about a mercenary National Health panellist, except, of course, Paul McCartney and George Harrison.

When we had talked ourselves out, McCartney took me down to the basement and showed me some of his home movies, informally entitled “Till Next Spring Then” and “The Defeat of The Dog.” They were not like ordinary people’s home movies. There were over-exposures, double-exposures, blinding orange lights, quick cuts from professional wrestling to a crowded car park to a close-up of a television weather map. There were long still shots of a grey, cloudy sky and a wet, grey pavement, jumping Chinese ivory carvings, and affectionate slow-motion studies of his sheep-dog, Martha, and his cat. The accompanying music, on a record-player, and faultlessly synchronised, was by the Modern Jazz Quartet and Bach.

Having enjoyed the afternoon. I asked for a signed record. He got out a copy of “Revolver.” “To anyone special?” he asked, pen poised. “Oh, just anyone,” I said, dimpling coyly. I didn’t look at the inscription until I was in the taxi. The sleeve was inscribed:

“To Anyone, Kindly, James Paul Augustus McCartney of Britain.”

The Beatles have a deadly sense of humour.

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.