Thursday, November 14, 2019

Interview for Billboard

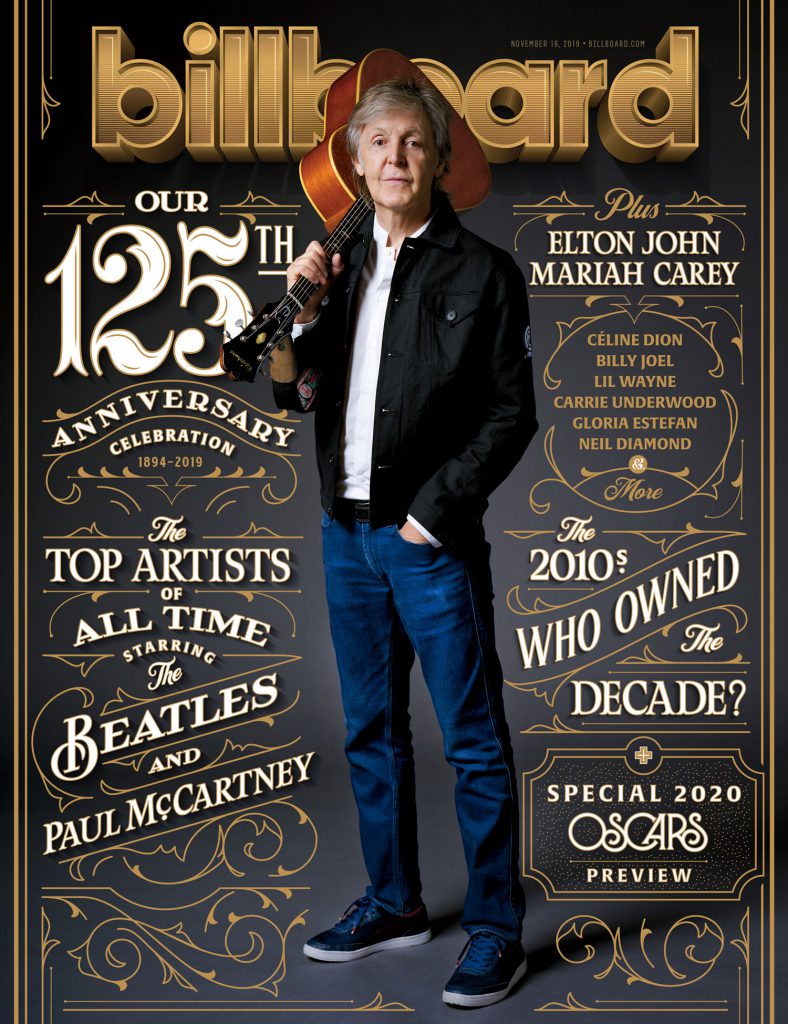

Paul McCartney on Life, Art and Business After the Beatles

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Thursday, November 14, 2019

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Previous interview Sep 27, 2019 • Paul McCartney interview for paulmccartney.com

Article Oct 16, 2019 • "The Beatles - The singles collection" announced

Album Oct 25, 2019 • "What's My Name" by Ringo Starr released globally

Interview Nov 14, 2019 • Paul McCartney interview for Billboard

Album Nov 22, 2019 • "Home Tonight / In A Hurry" by Paul McCartney released globally

Album Nov 22, 2019 • "The Singles Collection" by The Beatles released globally

Next interview Dec 12, 2019 • Paul McCartney interview for BBC Radio 4

Officially appears on Back To The Egg

Officially appears on The Beatles (Mono)

Officially appears on Let It Be / You Know My Name (Look Up The Number)

The interview below has been reproduced from this page. This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

He’s No. 1 in Billboard chart history with The Beatles — plus No. 12 on his own. Now, at 77, Paul McCartney is writing a musical and reclaiming the rights to his Beatles songs in the United States: “If you’re in it, why not win it?

It’s hard to imagine Paul McCartney coming into the office. He has always been casually cool — first as a mop-topped Beatle, then as the laid-back leader of Wings, and most recently as a stadium-filling solo star. But on a recent sunny London Monday, in the Soho Square townhouse headquarters of his company MPL, there he is, humming to himself and dancing slowly across his cozy office — imposing desk on one end, comfortable sofa on the other — as a Wurlitzer jukebox plays “Friendly Persuasion” by Pat Boone. “I like the melody,” he says.

At 77, McCartney is well past the age — to say nothing of the tax bracket — at which most men are content to stay home. And it would be hard to argue that he wasn’t entitled to take it easy: The Beatles are officially the No. 1 act on Billboard’s ranking of the top-charting artists of all time, and he’s No. 12 as a solo artist (including his work with Wings). Yet he’s as active as ever. Last fall he released Egypt Station, which became his first No. 1 album in the United States since 1982’s Tug of War, after which he embarked on a Freshen Up tour that grossed $129.2 million, according to Billboard Boxscore. He still comes into the office, though, “maybe a day a week,” he says. “And I’m on the phone and email.”

Long before every pop star considered themselves CEOs, McCartney set up MPL, as The Beatles were breaking up, to run his own business out of a small office in this building (which he bought years later). At the time, music manager Allen Klein had taken control of Apple Records, the group’s company, and the resulting disagreements over financial and other matters were driving the bandmembers apart. “I just thought, ‘I’ve got to do my own little Apple,’ ” remembers McCartney.

What started as a personal office, with his late wife Linda’s friend as a secretary, turned into a company that gradually acquired an array of publishing rights — including McCartney’s post-Beatles music; songs by Buddy Holly, Carl Perkins and Frank Loesser (including “Baby, It’s Cold Outside”); standards like “Autumn Leaves,” “One for My Baby (And One More for the Road)” and “The Christmas Song” (“Chestnuts roasting on an open fire…”); and even the original music for Grease. Perhaps most exciting: McCartney says he’s in the process of getting back his share of the U.S. rights to his Beatles songs from Sony/ATV Music Publishing, although the company still owns international rights. (Sony/ATV declined to comment.)

As he works on a musical based on It’s a Wonderful Life, among other projects, McCartney is also curating his legacy. He’s overseeing a series of archival releases of his old Wings and solo albums, which he owns the rights to. And he still plays an active role in archival Beatles projects, through Apple Records: He talks about changing the direction of the book that came with the recent Abbey Road reissue, and he has begun to look over the original footage shot for the Let It Be movie, with an eye toward releasing it in some form.

As we sit on the couch, surrounded by a museum’s worth of memorabilia — a leather-bound book of his lyrics on the shelf; the art deco statuette that was photographed in a Switzerland snowbank for the cover of Wings Greatest — McCartney talks openly about The Beatles, his business and what’s next on the horizon. He’s relaxed and friendly, at one point pulling out an acoustic guitar to play the riff he contributed to a song he wrote with Kanye West. He seems genuinely pleased to chat about his historic chart success, and he’s willing to talk about pretty much anything — except slowing down. “If you’re in it,” he says, “why not win it?”

Does it surprise you that The Beatles are the highest-charting act in Billboard history?

That’s fantastic. They were a great group.

They? It was you!

They. You know, I wasn’t the group. We were a great group, though. The more I listen, the more I’m amazed, because a lot of that stuff was live. You listen to the Ed Sullivan performances and you think, “Wow.”

Last year you said that you’re still “very competitive.” Does that extend to the pop charts?

I’m competitive with anything. We started off in my auntie’s back parlor, banging away on three guitars — me, John [Lennon] and George [Harrison] — and we managed to get gigs in Liverpool, and then play the Cavern Club. We were always trying to succeed — I think everyone is.

You’re already No. 1, though — where do you go from there?

You could have said when we got our first No. 1, “Well, you’ve done it, boys,” or when we got our 10th. But those were like unexpected bonuses. They were the bonuses we wanted, but we were just trying to get better and develop. That was the force behind The Beatles: We’d do one song, and it’d be a hit, and instead of doing another with the same formula, we’d say, “OK, we’ve done that.” You listen to The Beatles’ output and no two songs are alike.

So it matters to you that Egypt Station was No. 1?

Yeah. When you do something, you kind of do it for yourself, but at the same time, you want people to hear it and judge whether it’s any good. So you put a bit of effort into thinking, “How should we best do this?” And as time goes by and the parameters change, you think, “How do we do it now?” We don’t just put out a single and hope for the best — there’s streaming and things to consider.

I’ve got a great team, and my main thing is: Let’s try and keep it exciting. I’ve got people who will say, “Why don’t you play Amoeba in Los Angeles?” [which McCartney did in 2007] or “Why don’t you play Grand Central Station” [in New York in 2018]?

The Beatles changed pop music by writing their own material, but these days most pop hits are written by several songwriters. Did you get a sense of what that’s like when you worked with Kanye West?

I had no idea what was going to happen. I didn’t want it to be at his house or my house, because it could be awkward if one of us wanted to leave. So we met on neutral ground — a cottage at the Beverly Hills Hotel — and I showed up with a guitar and my roadie, and we had a keyboard and a bass. I was sitting around, strumming the guitar — that’s normally how I start a song — and Kanye was looking at his iPad, basically scrolling through images of Kim [Kardashian]. So we were telling stories, and at one point I told him how “Let It Be” came from a dream about my mother, who had died years before, where she said, “Don’t worry, just let it be.” He said, “I’m going to write a song about my mother,” so I sat down at this little Wurlitzer keyboard and started playing some chords, and he started singing. I thought, “Oh, are we going to finish this?” but that was that. And it became “Only One.”

It’s a very different way of writing than what you’re used to.

It’s this modern process that I was happy to open myself up to — you’ve got loads of stuff, and the skill is to distill it. I was sitting around, just strumming a little groove (Strums his guitar.) and nobody said, “Let’s make a song of that.” But months later I got a song with Rihanna on it and I said, “Where am I?” I didn’t recognize it because they changed the key [on the guitar riff]. I thought that record was great. Every time we go to a club, my wife Nancy requests it.

How involved are you in your company, MPL, day to day?

When we first did this, I said, “I could be on tour for a year — don’t expect me to come in.” Then, having said that, it was like, “Well, I’m in London next week, I’ll pop in.” And that’s still how it still happens: I’ve got so much brain, and 90% of it has to be free for songs and art. If I block that out with finance, I’m sunk. So 10% of me can think about where we’re going, but I keep the rest open to do various artistic things.

Why did MPL first start to acquire song catalogs in the 1970s?

When we came down from Liverpool, I thought — naively — when you earn money, you put it in the bank. Then you meet accountants who say no, no, no — you have to invest it. Linda’s dad and brother [Lee and John Eastman] were my lawyers, and they’re brilliant, and Lee rang me up at one point and said, “One of my clients wants to sell his publishing company.” It was Buddy Morris [who had founded Edwin H. Morris Music]. He named a very large figure — basically all I had at the time. And I said, “Are you sure this is a good move? Send me a list of the songs it publishes.” I looked at the list, and it had “Stormy Weather,” “The Christmas Song” — you know, “Chestnuts roasting on an open fire” — and I thought, “Here goes nothing! Well, here goes everything!” That was the source of the standards [that MPL publishes], and it was one of the great American catalogs.

Can I ask how much you paid for it?

You can ask — and I know — but I can’t tell. It was a very large amount in those days. But it turned out to be really good.

These kinds of things happened. Someone said, “You’re the publisher for this new show that’s trying out in Boston, and we’re paying them to keep it going — do you want to continue paying?” The company had signed the writers, and we were helping fund the show. And I said, “Let’s just keep going.” Well, that turned out to be Annie.

So you publish “Hard Knock Life”?

Yeah. So how pleased was I when JAY-Z used it! It’s luck. But The Beatles was luck! How did these four guys in Liverpool get to meet each other? We weren’t at the same school.

On some level, were MPL’s publishing acquisitions a reaction to not owning your own Beatles songs?

I think so. John and I felt screwed out of our rightful recompense. With our original agreement with Dick James, Dick went to us and said, “You can have your own company.” And we were young boys — we were young and foolish, but we were beautiful! And we said, “Wow, great.” So he gave us our own company, Northern Songs, which was 49% us, 51% him, which gave him voting control. Later, we went to him a couple of times and said, “Dick, now that we’ve done all this stuff, can we have a raise?” And he basically said, “I’m sorry, I can’t — you’re under contract.” I now know he could’ve just said, “I’ll give you a new contract.” So when I had the opportunity to have another publishing company so cleanly, this was great.

Speaking of which: In January 2017, you sued Sony/ATV to make sure you could reclaim your half of the U.S. publishing rights to your Beatles songs. What happened?

I don’t want to talk too much about it, but there’s a certain right under U.S. law where these things revert to me. [For songs written before 1978, creators can file for “copyright termination” 56 years after works were registered to get back the rights to their work in the United States, although there have been questions about how this applies to contracts originally signed in other countries.] Sony didn’t agree. And then they came to us, tail between their legs [to settle, which resulted in a confidential June 2017 deal], and said, “One condition is that you don’t really talk about it.” Believe me, I would love to give you every single detail. It’s only U.S.

You tour in an interesting way, in that you have a promoter, Barrie Marshall, but no booking agent.

That’s how we’ve always done it. I sit in this office with Barrie, and he says something like, “If you want to tour next year, you can go to South America or wherever,” and he puts some stuff together, and I either say “I don’t fancy that” or “This looks good,” and then he books the places, and we do it.

You also own your own master recordings, although you now license new ones to Capitol Records. How involved are you in these reissues, and do they ever make you reevaluate those old albums?

I go through these songs, and when we remaster, I go to Abbey Road, and it’s like popping into the office. And I get to hear these songs I haven’t heard forever. “Arrow Through Me” was one I heard recently, and I thought, “Geez, that’s a good track, and it’s got a great little brass riff on it.” Funky little track.

There have been some interesting Beatles reissues recently, like the 50th-anniversary editions of the White Album and Abbey Road. How much is left in the proverbial vault? Will they ever rerelease the Let It Be movie?

As we prepared the Anthology series, George and I were joking that we should call the next album Scraping the Bottom of the Barrel. These things are like photos of yourself from when you were young that you thought were terrible. Now, you think they look good. And this seems to be an endless barrel — stuff keeps coming up. One of the things we’re working on is the 58 hours of footage that turned into the Let It Be film. The director tells me that the overall impression is of friends working together, whereas because it was so close to The Beatles’ breakup, my impression of the film was of a sad moment. Something’s going to come out from that footage. It won’t be called Let It Be, but there will be something.

Speaking of movies, did you see Yesterday? What did you think?

That began when Richard Curtis, who [directed] Love Actually, wrote to me with the idea. And I thought, “This is a terrible idea,” but I couldn’t tell him, so I said, “Well, that sounds interesting — good luck.” I didn’t think anything more of it. Then someone said Danny Boyle would direct it, and I thought, “They must think they can pull it off.” And I thought nothing more of it until they asked if I wanted to see a screening. I asked Nancy, and we said, “Let’s go, you and me, on a date to the cinema.”

You saw it in a normal theater?

We were in the Hamptons in the summer and there it was, so we got two tickets and walked in when the cinema went dark. Only a couple of people saw us. We were in the back row, giggling away, especially at all the mentions of “Paul McCartney.” A couple of people in front of us spotted us, but everyone else was watching the film. We loved it.

You’re also now writing a musical based on It’s a Wonderful Life. How’s that going?

The reason I never wanted to do a musical is I couldn’t think of a strong enough story. But a guy I’ve known since school in Liverpool became a theatrical impresario in London [Bill Kenwright], and he rang me up and said, “I’ve got the musical rights to It’s a Wonderful Life.” That’s a strong story. So I met with the writer, Lee Hall, and I asked him to write the first 20 minutes of how he sees this as a play. So I was on holiday in the Hamptons, and I had lots of free time…

And you started working?

(Laughs.) This isn’t working! I don’t work — I play! So I read it and thought, “That’s a good opening, I like this,” and I sat at the piano and threw this melody at these dummy lyrics he had written. This was August. I sent it to them, and they said, “You’ve nailed it.” So it’s going well.

In 2015, Kanye West said at an iHeartMedia Music Summit that the one question he asked you when you worked together was about what sex was like in the ’60s.

“Pretty sensational.” Sometimes Nancy will see a girl in the street and say, “Wow, she’s beautiful.” And I’ll say, “She sure is, but, darling, she’s young.” Everyone’s beautiful when they’re young. That was the ’60s. We were young, they were young, it was quite a time.

You performed two songs with Ringo Starr at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles last summer, and you recorded a John Lennon song together for his new album. Do you still talk a lot?

Yeah. Whenever he’s over here or we’re over there, we go to dinner or whatever. During that performance at Dodger Stadium, I was singing “Helter Skelter,” and I said, “I’m going to get my singing done and then just look at this guy. And there he was — Ringo, in person, drumming up a storm on “Helter Skelter,” and I was just drinking it in. It was a beautiful moment.

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.