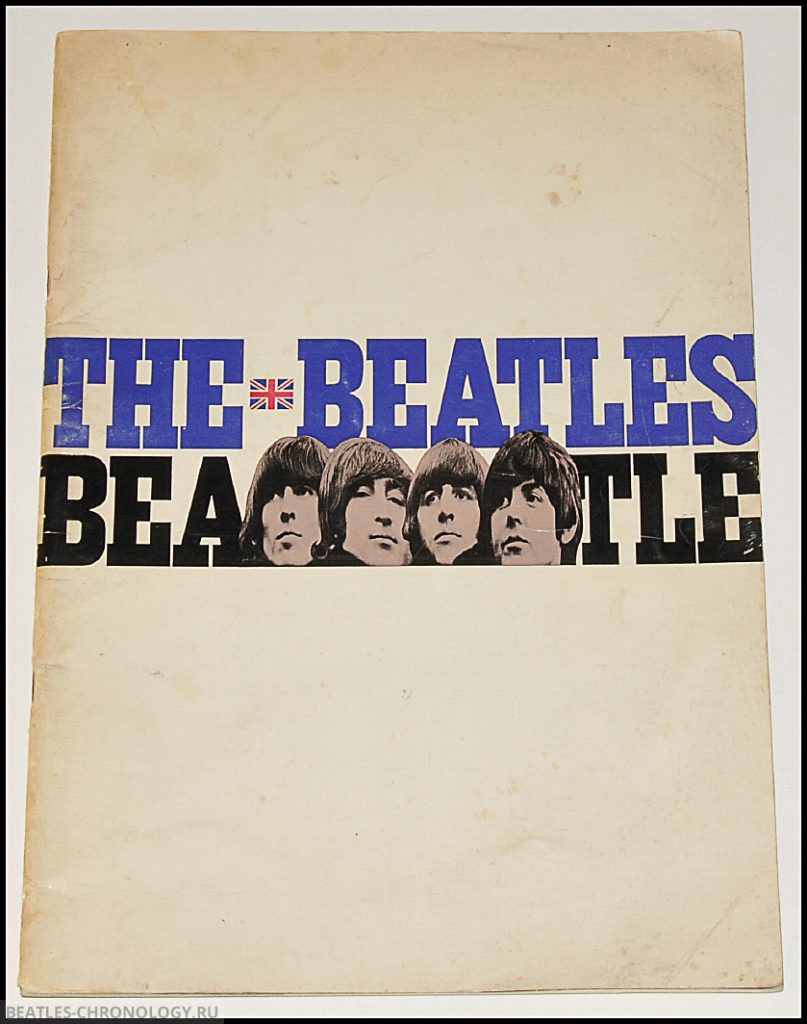

Thursday, June 30, 1966 › Monday, July 4, 1966

1966 Japan and Philippines Tour

By The Beatles

Last updated on November 4, 2023

Thursday, June 30, 1966 › Monday, July 4, 1966

By The Beatles

Last updated on November 4, 2023

From Wikipedia:

The English rock group the Beatles toured West Germany, Japan and the Philippines between 24 June and 4 July 1966. The thirteen concerts comprised the first stage of a world tour that ended with the band’s final tour of the United States, in August 1966. The shows in West Germany represented a return to the country where the Beatles had developed as a group before achieving fame in 1963. The return flight from the Philippines to England included a stopover in Delhi, India. There, the Beatles indulged in two days of sightseeing and shopping for musical instruments while still under the attention of the press and local fans.

The concerts were well attended yet provided the band with little in the way of artistic fulfilment. The programme was in the package-tour format typical of the 1960s, with two shows per day, several support acts on the bill, and the Beatles’ set lasting around 30 minutes. The band’s setlist included their new single, “Paperback Writer“, but no songs from their recently completed album, Revolver. Often marked by poor playing, the shows highlighted the division between what the group could achieve when performing live as a four-piece with inadequate amplification and the more complex music they were able to create in the recording studio. Concerts at the Circus-Krone-Bau in Munich and the Nippon Budokan hall in Tokyo were filmed and broadcast on local television networks.

The tour signalled a change in the Beatlemania phenomenon, as harsh measures were used to restrain crowds for the first time and the band became a symbol of societal division between conservative and liberal thinking. The bookings at the Budokan, a venue reserved for martial arts, offended many traditionalists in Japan, resulting in death threats to the Beatles and a heightened police presence throughout their stay. In Manila, the band’s nonattendance at a social engagement hosted by Imelda Marcos led to a hostile reaction from citizens loyal to the Marcos regime, government officials and army personnel. The Beatles and their entourage were manhandled while attempting to leave the country and forced to surrender much of the earnings from the group’s two shows at the Rizal Memorial Stadium.

On their return to London, the Beatles were outspoken in their condemnation of the Philippines. As a result of the events in Manila, the band lost faith with their longtime manager, Brian Epstein and made the decision to end their career as live performers that year. By contrast, the stay in Tokyo established an enduring bond between the Beatles and Japan, where each of the band members visited or performed in the decades following the group’s break-up in April 1970.

Background

“… when London was the best place on earth and they were the best people to be, they had to do the one thing they wanted to do the least; they had to leave. It was summer and it was written in the gospel according to Brian that in summer they went out on tour.”

Former Beatles assistant Peter Brown, 1983Brian Epstein, the Beatles’ manager, had intended that 1966 would follow the format of the previous two years, in which the Beatles had made a feature film with an accompanying soundtrack album, toured in North America and select countries during the summer months, and then recorded a second album for a pre-Christmas release. Following the group’s UK tour in December 1965, however, the band members decided to reject the planned film project, an adaptation of Richard Condon’s novel A Talent for Loving, for which Epstein had purchased the film rights. The band therefore had an unprecedented three months free of professional engagements. The group resumed work in early April, when they began recording Revolver, an album that reflected a more experimental approach as well as the increasing division between the music they made as live performers and their studio work. The band briefly interrupted the sessions to perform at the NME Poll-Winners Concert on 1 May.

During the early months of 1966, Epstein arranged bookings for the Beatles to play a series of concerts beginning in late June, in West Germany, Japan and the Philippines. These locations comprised the first leg of a world tour that would resume on 11 August, when the group embarked on their third US tour. When discussing a possible itinerary in New York on 3 March, Epstein had said that the Beatles were likely to play in Britain also but made no mention of the Philippines. Concerts in what was then the Soviet Union were also under consideration.

The band completed work on Revolver on 22 June and flew to Munich the following day to begin the tour. According to author Jonathan Gould, the Beatles would gladly have stayed in Britain rather than continue to perform in halls filled with screaming fans. The band’s dedication to completing Revolver, together with their lack of touring experience since December 1965, ensured that they were under-rehearsed for the concerts. Author Philip Norman writes that the knowledge that they would not be heard above the hysteria of their fans was another factor behind the group’s failure to rehearse adequately for the tour.

Repertoire, tour personnel, and equipment

Given the complexity of their new recordings, the band did not include any of the songs from Revolver in their 1966 setlist. Author and critic Richie Unterberger writes that this omission has been interpreted as laziness by some commentators, yet it was in keeping with the Beatles’ policy not to perform any unreleased material. Their current single, “Paperback Writer“, was included, but as with the few selections from Rubber Soul they performed live – “Nowhere Man” and “If I Needed Someone” – the Beatles were unable to capture the intricacies of the multi-track recording in concert. The set comprised eleven songs and lasted just over 30 minutes. Aside from the introduction of “Paperback Writer” (in place of “We Can Work It Out“), it was relatively unchanged from the 1965 UK tour. “Rock and Roll Music” became the opening song, while Ringo Starr’s moment as the featured singer, “Act Naturally“, was replaced by “I Wanna Be Your Man“. The Beatles played “Yesterday” – which had previously been a Paul McCartney solo performance, on acoustic guitar – with electric group backing for the first time. According to author Jon Savage, “It was a strange set … Rockers were interspersed with slow or mid-paced numbers, preventing any excitement from building.”

The Beatles’ entourage consisted of Epstein, press officer Tony Barrow, road managers Neil Aspinall and Mal Evans, and Peter Brown, Epstein’s assistant. Robert Whitaker, a photographer who regularly worked with the Beatles during this period, documented their time in Germany and Japan. In addition, Vic Lewis, Epstein and Brown’s colleague at the management company NEMS, joined the tour party in Japan, having helped arrange the Far East concerts. The band’s chauffeur, Alf Bicknell, was also present in Tokyo and Manila.

The Beatles’ main instruments were Epiphone Casino guitars for John Lennon and George Harrison, McCartney’s Höfner “violin” bass, and Starr’s Ludwig drum kit. After adopting the Epiphone as his stage guitar for 1966, beginning with the NME Poll-Winners Concert, Lennon continued to use it throughout the Beatles’ career. The band used new 100-watt Vox amplifiers throughout the tour. Harrison played his Rickenbacker 360/12 guitar on “If I Needed Someone”, while a photo taken by Whitaker shows that Harrison’s Gibson SG and McCartney’s Rickenbacker 4001 were also among the guitars they took to Japan. […]

Japan – Ideological concerns and controversy

The Beatles’ flight to Tokyo stopped in Anchorage, Alaska late on 27 June, local time, and was grounded there due to the presence of a typhoon over Japan. Epstein arranged for the Beatles to wait out the delay at Anchorage’s Westward Hotel, where the band’s presence instantly attracted a crowd of local fans, who serenaded them from the street below. The flight finally arrived at Haneda Airport in Tokyo in the early hours of 29 June, according to a report by Dudley Cheke, a chargé d’affaires at the British Embassy. Alternatively, an arrival time of around 3.30 am on 30 June is given by Beatles biographers Barry Miles and John Winn and in a 2016 Tokyo Weekender article about the visit.

The Beatles served as cultural ambassadors in Japan, where the authorities had viewed the band in an unfavourable light until their appointment as MBEs in 1965. The visit had been the subject of national debate and coincided with an era in which Japan sought to re-establish its cultural identity, following the country’s defeat in World War II. While the more progressive-minded elements of the population welcomed the spirit of change and youthful optimism that the Beatles represented, traditionalists were opposed to the band’s influence. To meet Epstein’s requirement of $100,000 (equivalent to $800,000 in 2021) for each performance, the 10,000-seat Nippon Budokan hall was chosen; tickets were priced at twice the rate of any previous visiting pop act.

The announcement that the concerts were to take place at the Budokan – a venue reserved for martial arts, as well as a shrine to Japan’s war dead – outraged the country’s hardline nationalists, who vowed to intercede and stop the proceedings. This issue, combined with a written death threat that the Beatles had received while in Hamburg, ensured that security around the group was extreme throughout their stay. In an operation that compared with Japan’s measures when hosting the 1964 Olympic Games, around 35,000 police and fire brigade personnel were mobilised to protect the Beatles.

Japan – Arrival and confinement

The four band members descended from the aircraft dressed in happi coats bearing the JAL logo. Their attire was a publicity coup for the airline, who, recognising the value of being associated with the Beatles’ financial success, had instructed one of its First Class flight attendants to ensure that the band emerged wearing these traditional Japanese coats. Faced with a wall of glaring lights, the four musicians believed they were waving to a throng of fans, as was usual when they arrived in a new country. In fact, they were surrounded by security personnel, and only twenty members of the public were present to witness their arrival. Supervised by a large police presence, the band’s fans were instead organised in groups along the road into the city. In a 2016 feature article on the Beatles’ Tokyo concerts, The Japan Times said that the photograph of the group dressed in JAL happi coats and descending from the plane had become “an iconic image of the Beatles’ visit”.

The Beatles were accommodated in the Presidential Suite of the Tokyo Hilton. For the duration of their stay in Japan, the band members were confined to the suite, aside from a single press conference and the concert performances. During the press conference, held in the afternoon of 30 June, Lennon spoke out publicly against the Vietnam War on the Beatles’ behalf. This marked the first time that the band had spoken out against the war in one of their press conferences, and followed Lennon and Harrison’s warning to Epstein before the tour that they were no longer prepared to stay silent on this issue.

A scheduled group visit to Kamakura on 30 June was cancelled after the Beatles learned that the police could not guarantee their safety. Accompanied by one of their road managers, Lennon and McCartney each managed to venture out at one point, only to be escorted back to the hotel once they were discovered. Starr recalls that every time the Beatles had to leave for an engagement, the process was handled with military-style precision by their Japanese hosts. To lighten the mood, the band took to delaying their exit from the hotel suite, thereby causing consternation for the time-conscious security staff.

Japan – Concerts and reception

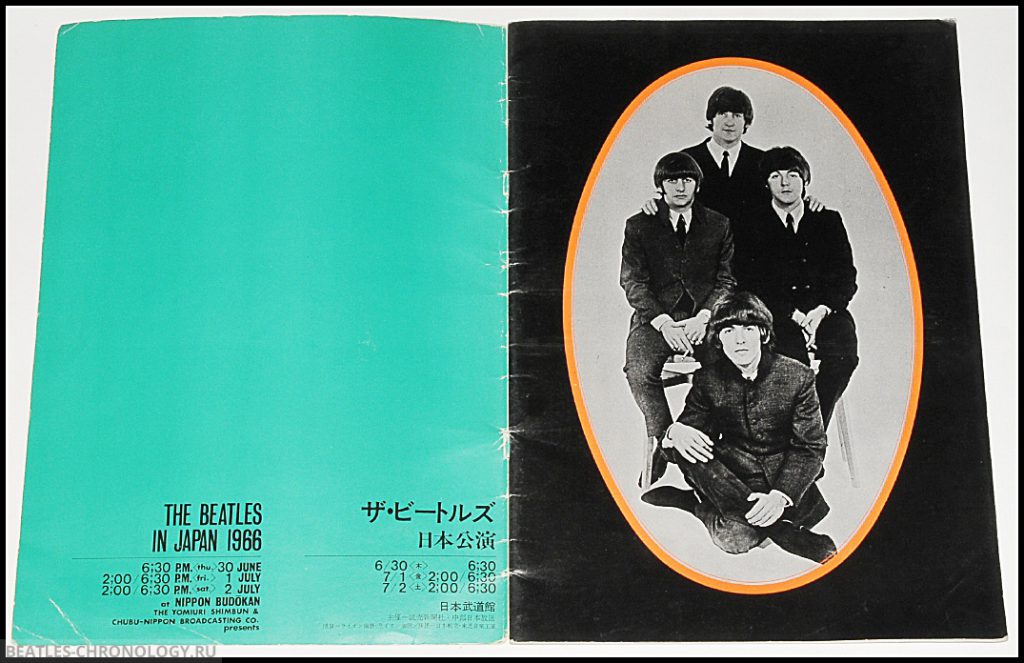

The band played the first of their five concerts at the Budokan on 30 June. The support acts were all local artists: the Drifters, Yuya Uchida, Isao Bitoh, the Blue Comets, Hiroshi Mochizuki, and the Blue Jeans. The shows were sponsored by the Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun and promoted by the Kyodo Agency. Both the 30 June performance, when the Beatles were dressed in dark green suits with red shirts, and the first show on 1 July, when they wore Hung On You-designed grey suits with thin orange stripes, were filmed in colour by Nippon TV. The footage was swiftly edited by the television company and combined with brief segments of documentary footage for broadcast, as The Beatles Recital: From Nippon Budokan, Tokyo, at 9 pm on 1 July.

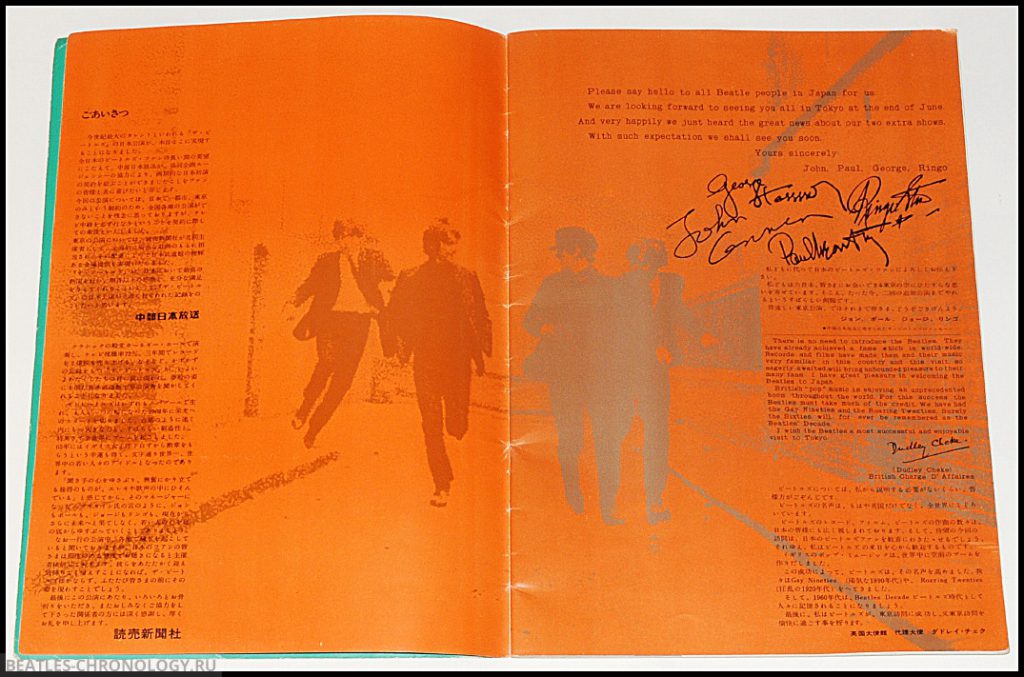

“In sober truth, no recent event connected with the UK – apart from the sole exception of the British Exhibition of 1965 – has made a comparable impact on Tokyo … Most commentators accepted them for what indeed they are – agreeable, talented and quick-witted young musicians.” – Michael Stewart, Britain’s ambassador to Tokyo, reporting on the Beatles’ visit

As ultranationalist students demonstrated in the city and outside the venue, the police presence was especially heavy inside and around the stage. According to Tony Barrow, the police feared that these right-wing students might have placed snipers in the audience. The stage itself was set on an 8-foot-high podium; all ground-floor seating had been cleared, meaning the audience was restricted to the hall’s first and second tiers. Concertgoers were warned that anyone standing up or cheering risked being arrested. The Beatles felt that the uniformed officers subdued the crowd, although the Japanese fans’ more reserved nature, relative to the group’s usual audiences, was also a factor. The band gave an especially poor performance on 30 June. According to Barrow and Aspinall, the group were humbled by this, having grown accustomed to not hearing themselves play, and resolved to perform well for the remainder of the Budokan dates.

During their extended periods in the hotel suite, the Beatles collaborated on a psychedelic-themed painting, using brushes and paints supplied by one of the visiting tradesmen, and listened to a tape of their new album. Whitaker photographed them at work and later commented: “I never saw them calmer, more contented than at this time. They were working on something that let their personalities come out … They’d stop, go and do a concert and then it was, ‘Let’s go back to the picture!'” Having struggled to find a title for the new album since their arrival in Munich, the Beatles finally settled on Revolver and informed EMI of their decision by telegram on 2 July. Whitaker recalled that, despite the hours of confinement in the Hilton, the atmosphere within the band while in Tokyo was “a crescendo of happiness”.

The Beatles and their entourage departed for Manila in the Philippines, via Hong Kong, mid-morning on 3 July. The Japanese press were highly favourable in their assessments of the Beatles’ visit, with the extreme security measures and the brevity of the band’s performances being the only areas of disappointment. Reporting to the Foreign Office in London, Dudley Cheke wrote that the cyclone over Japan had been replaced by a “Beatles typhoon”, which “swept the youth of Japan off their feet”. The Beatles embodied a new identity for the country’s youth; in the description of Japanese academic Toshinobu Fukuya, their presence had signalled that “one did not always have to obediently follow arrangements prescribed by adults; it was possible to follow one’s own path and still be socially and financially successful in life.” On 15 July, the Beatles’ stay in Japan was the subject of an article in America’s Life magazine.

Philippines – Arrival in Manila

The Beatles’ concerts in Manila had been anticipated by the local population on a level that Gould likens to the band’s 1964 tour of Australia, when the whole country appeared to view the visit as a national event. The group’s commitment to perform in the Philippines reinforced the country’s pro-Western image and was especially welcomed by the recently elected president, Ferdinand Marcos, and his wife Imelda. Although the Beatles’ tour itinerary originally listed the venue as the Araneta Coliseum, the concerts took place at the Rizal Memorial Stadium. The shows were promoted by Ramon Ramos and his company Cavalcade International Productions.

The Cathay Pacific flight carrying the Beatles landed at Manila Airport at 4.30 pm on 3 July. The nation’s police and military forces were in a state of high alert comparable with President Eisenhower’s 1960 visit; noting the prevalence of firearms, one of the Beatles asked whether there was a war taking place in the Philippines. In Starr’s description, the atmosphere was “that hot/Catholic/gun/Spanish Inquisition attitude”. Whereas the band and their entourage were usually given the privileges afforded to visiting diplomats, on this occasion, the four Beatles were hustled into a vehicle by armed men wearing civilian clothes. Harrison later recalled their alarm at being separated from Epstein, Aspinall and Mal Evans for the first time on a tour; his immediate concern was that, with their hand luggage left behind on the runway, the band would be arrested once their supplies of marijuana were discovered by the authorities. The Beatles were driven to the headquarters of the Philippine Navy on Manila Harbour and led to a press conference attended by 40 journalists. They were then escorted by military personnel to a luxury yacht owned by Don Manolo Elizalde, a wealthy Filipino industrialist, whose 24-year-old son wanted to host a party to show off the Beatles to his friends. Epstein finally caught up with the band before the yacht sailed out into Manila Bay. After spending several hours on board, he and the Beatles returned to the marina and, at 4 am, arrived at the Manila Hotel, where Epstein had booked accommodation.

Music journalists Jim Irvin and Chris Ingham have referred to the Beatles’ abduction at the airport and detainment on the yacht as a kidnapping. Alternatively, Turner writes that, unknown to Epstein, arrangements had been made between Ramon Ramos and Vic Lewis for the Beatles to spend the night on the yacht, since that presented a better security option than a city hotel. Aspinall, who had arrived at the marina with the Beatles’ hand luggage while they were out on the bay, said that their abduction was carried out by a militia gang who were rivals of the individuals presenting the upcoming concerts.

Philippines – Invitation to Malacañang Palace

Apart from McCartney, who went sightseeing with Aspinall, the Beatles slept in late on 4 July until woken by security staff intent on taking them to a party hosted by Imelda Marcos in their honour at Malacañang Palace. The event was scheduled for 11 am and had been announced in the previous day’s edition of The Manila Times. While the Beatles were unaware of this announcement, Epstein had already declined the invitation when they were in Tokyo. This was in keeping with his policy since 1964 regarding all embassy or other official functions to which the group were often invited while on tour. The 1966 itinerary mentioned only that the Beatles might “call in” at the palace at 3 pm en route to their first concert. Turner interprets the casual wording of this item as Ramos, faced with delivering on Imelda Marcos’s wishes, “burying the invitation in the small print, hoping for a compromise on the day”.

When confronted by Lewis, who was also woken by the presidential guards that morning, Epstein dismissed his suggestion and that of Leslie Minford, a chargé d’affaires at the British Embassy, that the Beatles should make an exception for the First Lady of the Philippines. The Beatles were equally adamant; when told by the guards that President Marcos was among the dignitaries awaiting their arrival, Lennon retorted: “Who’s he?” The band learned of the offence that Imelda Marcos had taken at their nonappearance while watching television at the hotel before leaving for the first concert. Footage from the palace was broadcast of the empty seats reserved for the four Beatles, children crying in disappointment, and the First Lady saying that the visiting musicians had let her down.

Philippines – Concerts and national backlash

The Beatles played the first of their two concerts at the Rizal football stadium at 4pm before a crowd of 30,000. The band performed on a small stage behind a wire fence. Pilita Corrales, the Reycards and the Downbeats were among the six local support acts. The second show took place at 8:30pm and was attended by 50,000 fans. The combined total of 80,000 was the largest audience to see the Beatles in concert on a single day. The band were well received by their fans, although the poor sound and the distance from the stage was a problem for many. In his review of the concerts, Filipino writer Nick Joaquin detected a halfheartedness in the Beatles’ performance and said that even the fans’ screams “seemed mechanical, not rapture but exhibitionism”. Another reviewer concluded: “The sound was terrible, The Beatles were terrific.”

After watching the continual news broadcasts at the hotel, between the two shows, Epstein resolved to record a message to explain the Beatles’ nonappearance at Malacañang Palace. The message was filmed by the government-owned Channel 5, at the Manila Hotel. When the segment was broadcast later that evening, however, the sound was distorted – a seemingly deliberate act – and Epstein’s explanation was rendered inaudible. Barrow recalls that a backlash against the Beatles was evident straight after the evening show at Rizal, when their convoy of cars was briefly trapped behind a closed gate and surrounded by a large crowd of “organised troublemakers”. As the NEMS representative who had dealt directly with the Filipino promoter, Lewis was taken away by police officers during the night and subjected to a three-hour interrogation for his role in “snubbing” the Philippines. Lewis contacted the British Embassy, where Minford, in a telegram to the Foreign Office, reported that “a technical hitch over payment of Philippine income tax” was likely to delay the Beatles’ departure. Death threats against the Beatles were reported at the embassy and at their hotel.

Philippines – Departure

The Beatles woke up early on 5 July in readiness for their flight to Delhi in India. After their requests for room service had gone unanswered, Evans went down to reception and found that all security protection inside the hotel had disappeared. The morning newspapers carried front-page stories condemning the Beatles for their failure to attend the engagement at Malacañang Palace. The tour party faced further intimidation initiated by Marcos loyalists. The Bureau of Internal Revenue presented a tax bill on the band’s concert earnings, which were still held by Ramos; this was despite a stipulation in NEMS’ contract with Cavalcade that any such tax would be paid by the local promoter. All assistance from the hotel staff was withdrawn, as was any police escort through the city traffic, leaving Epstein to call ahead and plead with the pilot of their KLM flight to delay his takeoff. On the way to the airport, their Filipino drivers appeared to forget the route; in another example of what Aspinall termed “obstacles [put] in our way”, a soldier sent their cars repeatedly around the same traffic roundabout.

“You treat like ordinary passenger! Ordinary passenger!” they were saying. We were saying: “Ordinary passenger? He doesn’t get kicked, does he?” – John Lennon, recalling the treatment the Beatles received at Manila Airport after inadvertently snubbing the Marcos regime

In Peter Brown’s description, when they arrived at the airport, it resembled an “armed military camp”. Aside from a heavy army presence, hundreds of irate citizens lined the path into the terminal building, where they harassed and jostled the tour party as each member walked by. Inside the terminal, on the instructions of Willy Jurado, the airport manager, the escalators had been turned off, and the band and their entourage were denied any assistance with musical instruments, amplifiers and luggage. The crowd from outside the building were then permitted into a glass-walled observation area, from which they continued their haranguing of the Beatles. The tour party moved into a large departure lounge, where uniformed men and others that Harrison recognised as the “thugs” from their arrival in Manila, began beating and kicking them, moving them from one corner of the room into another. Jurado later bragged about knocking Epstein to the ground and punching Lennon and Starr in the face, adding: “That’s what happens when you insult the First Lady.” Along with Alf Bicknell, Evans received a particularly thorough bashing after he intervened to shield the four band members from their attackers.

The tour party were finally allowed to board the aircraft. According to Barrow, the harassment continued as they crossed the tarmac leading to the steps up to the plane. Some of the band’s fans were also present; when they expressed sympathy for the Beatles, they too attracted scorn from the mob. McCartney recalled that, such was their relief once inside the cabin, “We were all kissing the seats.” An announcement then called Epstein off the plane to finalise the unpaid tax demand. Barrow and Evans were also told to disembark. After their passport irregularities had been sorted out, they both re-boarded and the plane was able to take off. Lewis then got into a heated argument with Epstein regarding the concert takings. Epstein admonished Lewis for focusing on money, given the ordeal they had all just endured, and asked him: “Who was it that screwed up the party invitation?”

Philippines – Aftermath

Soon after the Beatles had left Manila on 5 July, President Marcos issued a statement acknowledging that the group had not purposely snubbed the First Family. He attributed the violent scenes at the airport to citizens overreacting to a “misunderstanding”, and announced that he had lifted the tax on the band’s earnings in the Philippines. Although Brown, writing in his 1983 memoir The Love You Make, said that the Beatles’ performance fee had been received from Ramos in two instalments, subsequent evidence suggests that the band were not paid. In his concluding report to the Foreign Office, Minford mentioned that some individuals at the airport had used “unnecessary zeal” towards the Beatles and he credited Benjamin Romualdez, the brother of Imelda Marcos, with sorting out the episode.

Writing two weeks after the Beatles’ visit, Joaquin commented that the Philippines had been attracted to the band’s image without appreciating that, behind the image, their message was one advocating individuality, adventurousness and originality over tradition and order. Joaquin cited this underestimation as the cause of the Beatles’ recent problems and likened the group’s presence in Manila to Batman being transplanted to Thebes in Ancient Greece.

Stopover in India

Before leaving London, Harrison had arranged to disembark in Delhi with Aspinall on the return trip, and buy a top-quality sitar there. During the tour, the other Beatles had each decided to join the pair, although, after their troubles in Manila, all of the band would have preferred to return to London immediately. Their plane landed at night at Delhi’s Palam Airport. While the Beatles had assumed that they were unknown in India, they were welcomed by a crowd of 500 fans and journalists and forced to give a brief press conference. The group’s two-day stay in Delhi similarly came to resemble the stops throughout the tour in terms of media attention and periods of confinement in their hotel, the Oberoi.

On 6 July, the band managed to evade the fans camped out in front of the hotel and go to Connaught Place. There, they shopped for Indian musical instruments at Lahore Music House and the prestigious instrument-makers Rikhi Ram & Sons. Since their presence had soon attracted a crowd of fans, the Beatles arranged for the Rikhi Ram staff to visit them later at the Oberoi Hotel with a sitar for Harrison, as well as a sarod, tambura and tabla. The entourage were also given a tour of Delhi, during which their Cadillacs were chased by a vehicle carrying the head of the local Associated Press bureau. Once the journalist had received a comment from McCartney about the controversy in Manila, the tour continued on to villages outside the city. The primitiveness and poverty they saw there was a shock to the band. Starr described India as the first genuinely “foreign” country he had visited; Harrison found it sobering to realise that their Nikon cameras, which were a gift to the group from their Japanese promoter, “were worth more money than the whole village would earn in a lifetime”. Other locations they visited while in Delhi included the historic Red Fort and Qutb Minar.

At the Oberoi, the Beatles discussed the recent events in Manila and privately expressed their dissatisfaction with Epstein’s management of their tours. According to Brown, when Aspinall said that Epstein was already booking concerts for 1967, Lennon and Harrison insisted that their current tour would be their last. They relayed this decision to Epstein either at the hotel, where he was bedridden with a high fever, or during the flight to London. The decision was also informed by the band’s increasing dissatisfaction with the inadequate sound systems at the venues they played and the inane questions they faced at each press conference.

Return to England and fallout from Manila

The Beatles arrived at Heathrow Airport early morning on 8 July and immediately conveyed their bitterness over Manila in a television interview for ITV. Lennon said they would “never go to any nuthouses again” while McCartney accused their attackers of being cowards. Harrison said the only reason to return to the Philippines would be to drop a bomb on the country. Referring to this comment, Lennon wrote on a copy of the tour itinerary: “we all silently agreed.” Starr later described their ordeal in Manila as “the most frightening thing that’s ever happened to me”. Two days after the band’s return, it was announced that Freddie and the Dreamers had cancelled their upcoming concerts in the Philippines, as a gesture of solidarity with the Beatles.

Distraught at the group’s decision to stop touring, Epstein was diagnosed with glandular fever and went to a remote hotel in North Wales to recover. On 5 August, he was called away to the United States to ameliorate the controversy that had resulted from the publication of Lennon’s comment that the Beatles had become more popular than Christ. When the 1966 world tour resumed there on 12 August, the band were the subject of radio bans in some southern states and further death threats. According to Barrow, the decision to quit touring after 1966 was made without McCartney’s agreement and marked the first time that the Beatles had committed to a course of action without unanimous agreement among the four. McCartney said that he was finally persuaded to join the others’ way of thinking following the group’s concert at St. Louis, which took place on 21 August.

Legacy

Over the decades since the Beatles performed their first Asian concerts there in 1966, Japan has continued to occupy a significant place in the band’s legacy. After meeting his second wife, the Japanese artist Yoko Ono, in November 1966, Lennon enjoyed visiting the country during the 1970s. In December 1991, having never recovered his enthusiasm for performing live after the Beatles’ experiences, Harrison carried out his second of only two tours as a solo artist in Japan. McCartney and Starr have regularly toured the country since the late 1980s.

Following the controversy surrounding the Nippon Budokan’s first hosting of a rock concert in 1966, the hall has become the main venue for acts touring Japan. Writing in The Japan Times in 2016, Steve McClure said that the Beatles’ performances at the hall had “conferred on it a quasi-sacred status in rock mythology”. Among the fans who saw the Beatles perform there were future Japanese music-industry executives Aki Tanaka and Kei Ishizaka. Tanaka describes the concerts as “a social phenomenon” and credits them with inspiring “the birth of a real Japanese rock music scene”, in which local artists wrote their own songs rather than merely covering Western rock songs.

Steve Turner comments on the significance of the first leg of the Beatles’ 1966 world tour in terms of the development of the Beatlemania phenomenon, in that the band’s influence now incited “potential acts of terrorism”, just as their music had started to “fuel the fight between conservatives and liberals” in the countries they visited. Turner also views the brief stopover in India as important, since it represented the group’s formal introduction to a culture with which they became increasingly associated over the next two years.

For several years, the combined audience of 80,000 at the Rizal Memorial Stadium on 4 July 1966 stood as the world record for any act on a single day. The Marcoses were enjoying a honeymoon period in the mid-1960s as the Philippines’ American-style First Family, but the president later came to be seen as a dictator and, having amassed a personal wealth of up to $10 billion, fled to the United States after being deposed in 1986. They were indicted for racketeering, although Imelda Marcos was acquitted and returned to the Philippines, where she faced charges of corruption. Given these revelations, McCartney has said that the Beatles were “glad to have done what we did … We must have been the only people who’d ever dared to snub Marcos.” As of 2016, none of the former Beatles had ever returned to the Philippines, despite an attempt by Filipino musician Ely Buendia – in response to the promotional campaign for Starr’s 2015 album Postcards from Paradise – to lure Starr back to the country.

Things were so tense the whole time, I felt like I was a war correspondent.

Shimpei Asai – Photographer, on When The Beatles Visited Japan. #8DaysDVD

It was not long after New Year in 1966 when the first rumors began to circulate that the Beatles were coming to Japan. I remember meeting the promoter Nagashima Tatsuji of Kyōdō Kikaku (now Kyōdō Tokyo), who asked me for my personal impressions of the Beatles as people. I told him that the Beatles had been charming but that their manager Brian Epstein was a tough customer. It was a little after that that the group’s tour was confirmed.

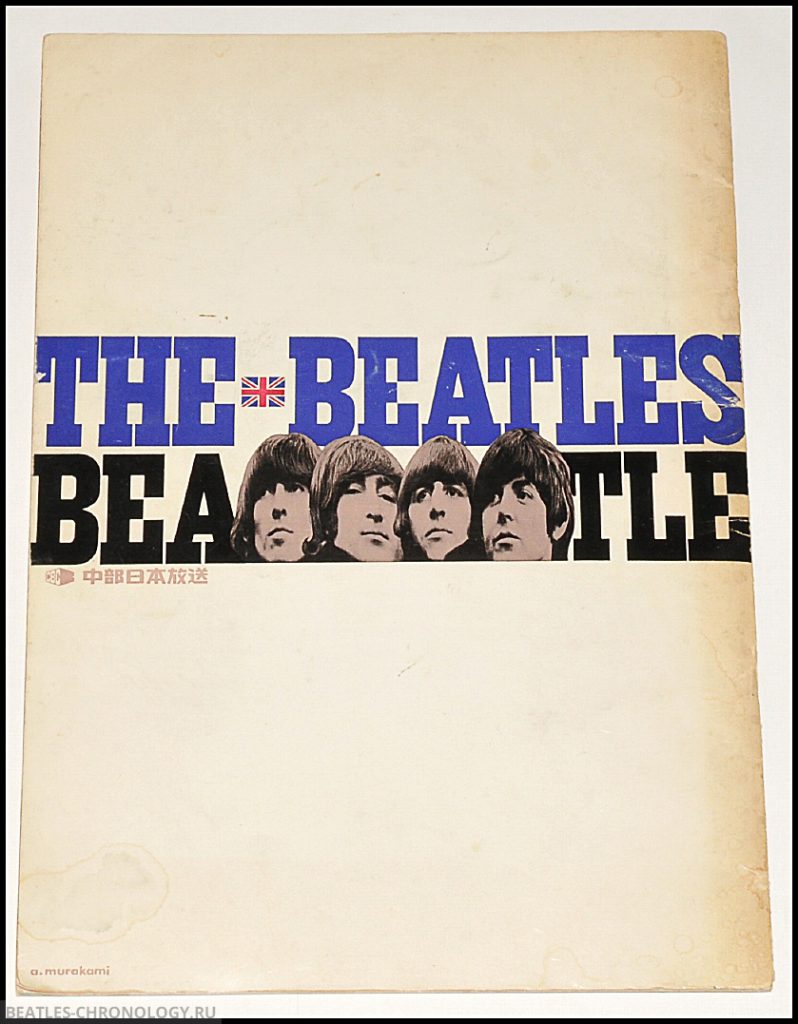

There were several major sponsors for the Beatles performances in Japan: Kyōdō Kikaku, the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper, and the Chūbu-Nippon Broadcasting Company. The tour was to involve five performances between June 30 and July 2, and applications for tickets had to be made by sending a postcard to the Yomiuri Shimbun, by entering prize competitions run by sponsors including Lion toothpaste and Toshiba Musical Industries (the distributors of the Beatles’ records in Japan) or by entering a ticket lottery by buying a round-trip air ticket on JAL. Many young women tried a combination of all these methods in a desperate attempt to get their hands on tickets.

While young people were generally enthusiastic about the Beatles, many older people objected to their style of music and long hair. Conservative adult audiences at the time preferred presentable, clean-cut groups like the Brothers Four, an American band who combed their hair into neat partings and sang unthreatening “college folk” music.

Hoshika Rumiko – From When Beatlemania Came to Japan | Nippon.com, July 28, 2016

We were locked up in the hotel for a long time, with various merchants coming around and showing us ivory and various gifts. People go to Tokyo to go shopping, but we couldn’t get out of the hotel. I once tried and a policeman came running after me. I did actually manage it, but he organised half the Tokyo police force to come with us. I had wanted to go and see the Emperor’s palace, but the policeman wasn’t too keen on the idea.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

When we first came to Japan we didn’t know what to expect, we didn’t know anything about the culture of Japan, and so it was very different from what we were expecting.It was very beautiful, it was very unusual for us. Where we come from, no woman would have got up to give her seat to a man, and we thought that was crazy. We tried to tell our girlfriends back in England to see if it was a good idea, but they didn’t think it was! But it was great, we had a great time. The whole thing was interesting because, as you know, [The Budokan] was originally just for sumo and martial arts, and there were one or two people who were a bit annoyed that we were playing Budokan because they thought that you shouldn’t play rock and roll in there. But we did it, we enjoyed it and the audience enjoyed it so the tradition of rock and roll has carried on and I have all of those memories – it’s lovely.

Paul McCartney – From paulmccartney.com, June 6, 2017

They had the seating exactly arranged in all the cars. Amazing efficiency, that we’d never seen the like of in Britain. When we went to the gig they had the fans organised with police patrols on each corner, so there weren’t any fans haphazardly waving along the streets. They had been gathered up and herded into a place where they were allowed to wave, so we’d go along the street and there’d be a little ‘eeeeekl’ and then we’d go a few more hundred yards and there’d be another ‘eeeeekl’

At the Budokan we were shown the old Samurai warriors’ costumes, which we marvelled at dutifully in a touristy kind of way: ‘Very good! Very old!’

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

In the hotel room we did a communal painting,- we all started a corner of the piece of paper and drew in towards the middle where the paintings met. This was just to pass the time away. I’ve seen it recently: it’s a psychedelic whirl of coloured doodles. The way the Japanese had organised going to the gig was very efficient. They all had walkie-talkies, at a time when you didn’t often see those. They came for us at exactly the time on the schedule.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

How different that was compared to, say, America, the year before? Was it more restrained?

[Robert Whitaker, photographer] I think it was the most elegantly promoted exhibition of their work, their music, that was prepared for them. America’s pretty rough and ready – ‘You are here, sing!’ Japan, they really seem to have great respect, so they had a beautiful hotel, nice cars to drive to and from the hotel. Budokan was a nice place. The promoters were very good. And the concerts were fairly restrained because I do not think Beatles fans in Japan knew quite how to scream like in Europe and America. So the Beatles could hear themselves singing. And they realised they were not singing in tune.

They were not used to it, were they?

No, they were not.

Were you aware, although the security was very tight because of the death threats, playing in the Budokan, the big martial arts place.

Yes, I’ve just been told it was a judo place, not sumo. I always thought it was sumo.

The Beatles were not allowed out of their hotel.

It was not so much a question of not being allowed. I think what the promoter and the security had thought, which is probably bullshit, that they might be mobbed, they might have somebody walk up and blast them

As they did eventually, kill John.

In the Anthology they talked about how the Beatles were regimented, how they had to be at a certain place at the certain time to the minute. Were you aware of that at the time?

It is evident in some of the photographs around the corner and in the window. They had to be there by the second. Of course, they did not adhere to that. They had to go on stage at a certain time, and it did not actually matter what time they arrived. They knew they were going on stage. I cannot really answer all these questions because I am not a Beatle, in fairness to them.

Was it evident to you at the time that they were fed up with touring?

When we got to The Philippines. Then again the whole thing changed again. They’d never been spat at or shoved around, – ‘pick up your own amplifiers, who the hell are you?’. I remember being in the aeroplane and them being very upset what had happened – and it wasn’t really their fault.

You had exclusive access to them in their hotel rooms. Did you become good friends of theirs?

With John – we’d see each other before and after – we were always good friends. Paul in Anthology I thought wrote very well about the ‘butcher sleeve’. George was always a bit against it. Ringo was always good fun. We all got on – we were all close in age. I was about 6 months older than John.

There are some very good photos in your book of The Beatles painting together. Was that their idea?

Pretty well, yes, what happened was that because they were impounded in their hotel, Paul had asked for some paints and started painting all sorts of things. The promoter suggested they all did a piece of artwork together that could be given away to charity. He provided all the paint all the brushes beautiful paper and we stuck a lamp in the middle of this paper – it was the only source of light I had to work with. It took two nights and days to do it. Whilst they were doing it they were playing an acetate of Revolver and deciding on the order of the tracks.

Robert Whitaker – From An Interview with Robert Whitaker – Beatles in London, October 6, 2016

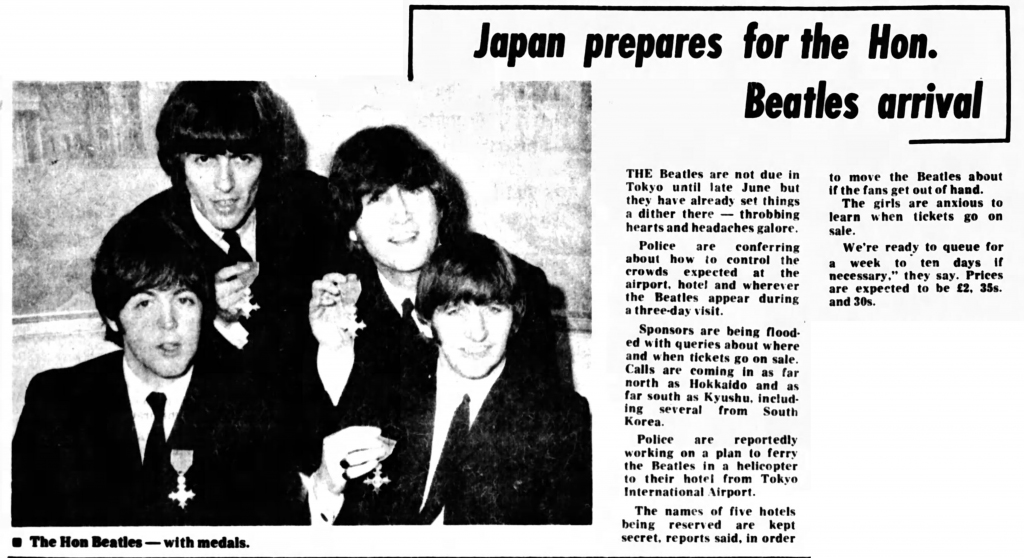

Japan prepares for the Hon. Beatles arrival

THE Beatles are not due in Tokyo until late June but they have already set things a dither there — throbbing hearts and headaches galore.

Police are conferring about how to control the crowds expected at the airport, hotel and wherever the Beatles appear during a three-day visit.

Sponsors are being flooded with queries about where and when tickets go on sale. Calls are coming in as far north as Hokkaido and as far south as Kyushu, including several from South Korea.

Police are reportedly working on a plan to ferry the Beatles in a helicopter to their hotel from Tokyo International Airport.

The names of five hotels being reserved are kept secret, reports said, in order to move the Beatles about if the fans get out of hand.

The girls are anxious to learn when tickets go on sale.

“We’re ready to queue for a week to ten days if necessary,” they say. Prices are expected to be £2, 35s. and 30s.

From Evening Post – May 3, 1966

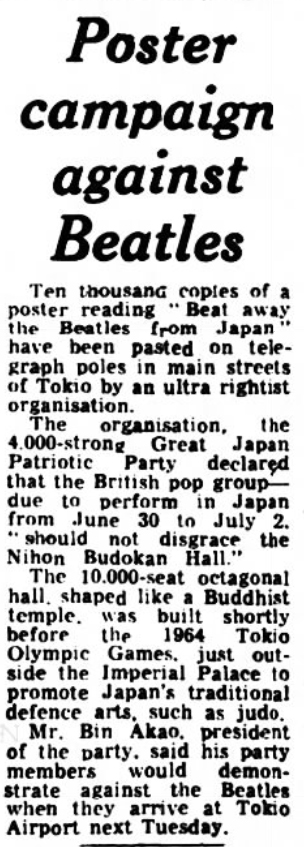

Poster campaign against Beatles

Ten thousand copies of a poster reading “Beat away the Beatles from Japan” have been pasted on telegraph poles in main streets of Tokyo by an ultra rightist organisation.

The organisation, the 4.000-strong Great Japan Patriotic Party declared that the British pop group — due to perform in Japan from June 30 to July 2 – “should not disgrace the Nihon Budokan Hall.”

The 10.000-seat octagonal hall, shaped like a Buddhist temple, was built shortly before the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games, just outside the Imperial Palace to promote Japan’s traditional defence arts, such as judo.

Mr. Bin Akao, president of the party, said his party members would demonstrate against the Beatles when they arrive at Tokyo Airport next Tuesday.

From Liverpool Echo – June 22, 1966

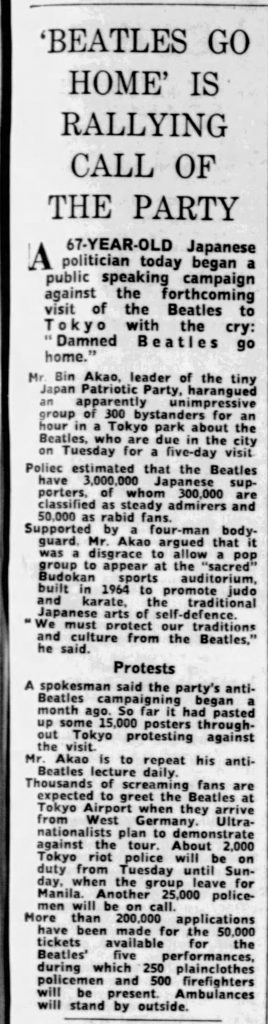

‘BEATLES GO HOME’ IS RALLYING CALL OF THE PARTY

A67-YEAR-OLD Japanese politician today began a public speaking campaign against the forthcoming visit of the Beatles to Tokyo with the cry: “Damned Beatles go home.”

Mr Bin Akao, leader of the tiny Japan Patriotic Party, harangued an apparently unimpressive group of 300 bystanders for an hour in a Tokyo park about the Beatles, who are due in the city on Tuesday for a five-day visit.

Police estimated that the Beatles have 3,000,000 Japanese supporters, of whom 300,000 are classified as steady admirers and 50,000 as rabid fans.

Supported by a four-man bodyguard Mr Akao argued that it was a disgrace to allow a pop group to appear at the “sacred” Budokan sports auditorium, built in 1964 to promote judo and karate, the traditional Japanese arts of self-defence. “We must protect our traditions and culture from the Beatles,” he said.

A spokesman said the party’s anti-Beatles campaigning began a month ago. So far it had pasted up some 15.000 posters throughout Tokyo protesting against the visit. Mr Akao is to repeat his anti-Beatles lecture daily.

Thousands of screaming fans are expected to greet the Beatles at Tokyo Airport when they arrive from West Germany. Utranationalists plan to demonstrate against the tour. About 2,000 Tokyo riot police will be on duty from Tuesday until Sunday, when the group leave for Manila. Another 25,000 policemen will be on call.

More than 200,000 applications have been made for the 50,000 tickets available for the Beatles’ five performances, during which 250 plainclothes policemen and 500 firefighters will be present. Ambulances will stand by outside.

From Evening Post and News – June 25, 1966

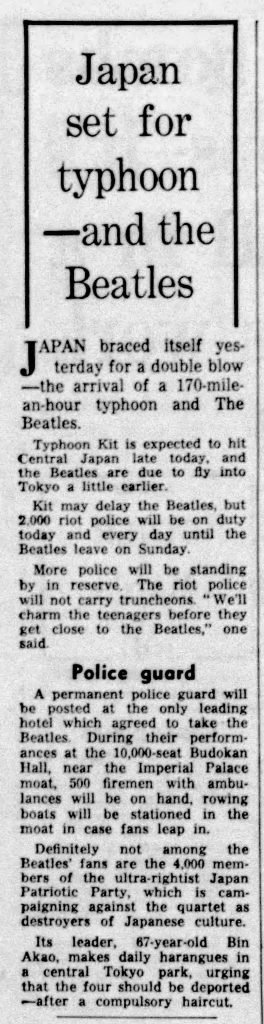

Japan set for typhoon — and the Beatles

JAPAN braced itself yesterday for a double blow — the arrival of a 170-mile-an-hour typhoon and The Beatles. Typhoon Kit is expected to hit Central Japan late today, and the Beatles are due to fly into Tokyo a little earlier. Kit may delay the Beatles, but 2,000 riot police will be on duty today and every day until the Beatles leave on Sunday. More police will be standing by in reserve. The riot police will not carry truncheons “We’ll charm the teenagers before they get close to the Beatles,” one said.

A permanent police guard will be posted at the only leading hotel which agreed to take the Beatles. During their perform-ance at the 10,000-seat Budokan Hall, near the Imperial Palace moat, 500 firemen with ambulances will be on hand, rowing boats will be stationed in the moat in case fans leap in.

Definitely not among the Beatles’ Ians are the 4,000 members of the ultra-rightist Japan Patriotic Party, which is campaigning against the quartet as destroyers of Japanese culture. Its leader, 67-year-old Bin Akao, makes daily harangues in a central Tokyo park, urging that the four should be deported — after a compulsory haircut.

From The Guardian – June 28, 1966

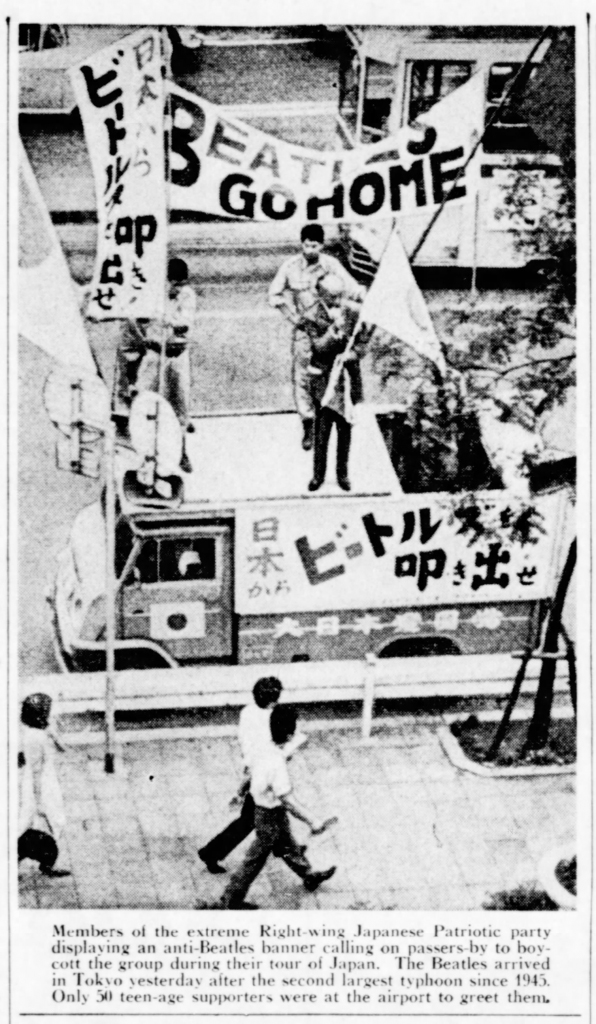

Members of the extreme Right-wing Japanese Patriotic party, displaying an anti-Beatles banner calling on passers-by to boycott the group during their tour of Japan. The Beatles arrived in Tokyo yesterday after the second largest typhoon since 1945. Only 50 teen-age supporters were at the airport to greet them.

From The Daily Telegraph – June 29, 1966

Beatles in Tokyo

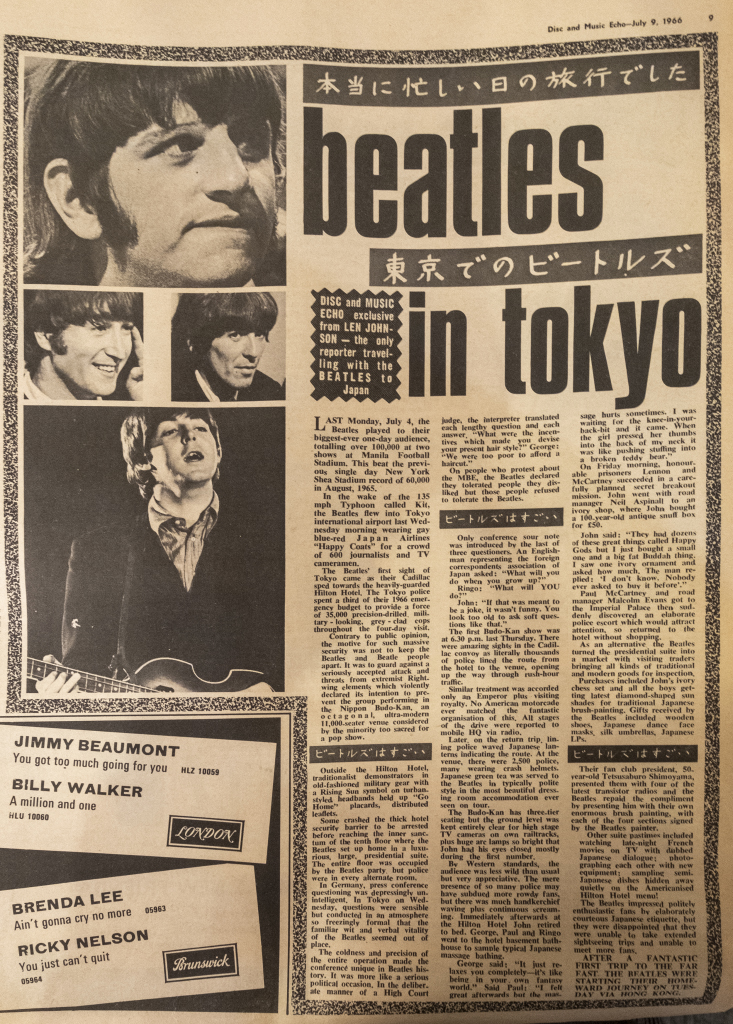

LAST Monday, July 4, the Beatles played to their biggest-ever one-day audience, totalling over 100,000 at two shows at Manila Football Stadium. This beat the previous single day New York Shea Stadium record of 60,000 in August, 1965.

In the wake of the 135mph Typhoon called Kit, the Beatles flew into Tokyo international airport last Wednesday morning wearing gay blue-red Japan Airlines “Happy Coats” for a crowd of 600 journalists and TV cameramen.

The Beatles’ first sight of Tokyo came as their Cadillac sped towards the heavily-guarded Hilton Hotel. The Tokyo police spent a third of their 1966 emergency budget to provide a force of 35,000 precision-drilled, military-looking, grey-clad cops throughout the four-day visit.

Contrary to public opinion, the motive for such massive security was not to keep the Beatles and Beatle people apart. It was to guard against a seriously accepted attack and threats from extremist Right-wing elements which violently declared its intention to prevent the group performing in the Nippon Budo-Kan, an octagonal, ultra-modern 11,000-seater venue considered by the minority too sacred for a pop show.

Outside the Hilton Hotel, traditionalist demonstrators in old-fashioned military gear with a Rising Sun symbol on turban-styled headbands held up “Go Home” placards, distributed leaflets.

Some crashed the thick hotel security barrier to be arrested before reaching the inner sanctum of tbe tenth floor where the Beatles set up home in a luxurious, large, presidential suite. The entire floor was occupied by the Beatles party, but police were in every alternate room.

In Germany, press conference questioning was depressingly unintelligent. In Tokyo on Wednesday, questions were sensible but conducted in an atmosphere so freezingly formal that the familiar wit and verbal vitality of the Beatles seemed out of place.

The coldness and precision of the entire operation made the conference unique in Beatles history. It was more like a serious political occasion. In the deliberate manner of a High Court judge, the interpreter translated each lengthy question and each answer. “What were the incentives which made you devise your present hair style?” George: “We were too poor to afford a haircut.”

On people who protest about the MBE, the Beatles declared they tolerated people they disliked but those people refused to tolerate the Beatles.

Only conference sour note was introduced by the last of three questioners. An Englishman representing the foreign correspondents association of Japan asked: “What will you do when you grow up?”

Ringo: “What will YOU do?”

John: “If that was meant to be a joke, it wasn’t funny. You look too old to ask soft questions like that.”

The first Budo-Kan show was at 6:30 p.m. last Thursday. There were amazing sights in the CadilIac convoy as literally thousands of police lined the route from the hotel to the venue, opening up the way through rush-hour traffic.

Similar treatment was accorded only an Emperor plus visiting royalty. No American motorcade ever matched the fantastic organisation of this. All stages of the drive were reported to mobile HQ via radio.

Later, on the return trip, Iining police waved Japanese lanterns indicating the route. At the venue, there were 2.500 police, many wearing crash helmets. Japanese green tea was served to the Beatles in typically polite style in the most beautiful dressing room accommodation ever seen on tour.

The Budo-Kan has three-tier seating but the ground level was kept entirely clear for high stage TV cameras on own railtracks, plus huge arc lamps so bright that John had his eyes closed mostly during the first number.

By Western standards, the audience was less wild than usual but very appreciative. The mere presence of so many police may have subdued more rowdy fans, but there was much handkerchief waving plus continuous screaming. Immediately afterwards at the Hilton Hotel John retired to bed. George. Paul and Ringo went to the hotel basement bathhouse to sample typical Japanese massage bathing.

George said: “It just relaxes you completely — it’s like being in your own fantasy world.” Said Paul: “I felt great afterwards but the massage hurts sometimes. I was waiting for the knee-in-your-back-bit and it came. When the girl pressed her thumbs into the back of my neck it was like pushing stuffing into a broken teddy bear.”

On Friday morning, honourable prisoners Lennon and McCartney succeeded in a carefully planned secret breakout mission. John went with road manager Neil Aspinall to an ivory shop, where John bought a 100-year-old antique snuff box for €50.

John said: “They had dozens of these great things called Happy Gods but I just bought a small one and a big fat Buddah thing. I saw one ivory ornament and asked how much. The man replied: ‘I don’t know. Nobody ever asked to buy it before’.”

Paul McCartney and road manager Malcolm Evans got to the Imperial Palace then suddenly discovered an elaborate police escort which would attract attention, so returned to the hotel without shopping.

As an alternative, the Beatles turned the presidential suite into a market with visiting traders bringing all kinds of traditional and modern goods for inspection.

Purchases included John’s ivory chess set and all the boys getting latest diamond-shaped sun shades for traditional Japanese brush-painting. Gifts received by the Beatles included wooden shoes, Japanese dance face masks, silk umbrellas, Japanese LPs.

Their fan club president. 50-year-old Tetsusaburo Shimoyama, presented them with four of the latest transistor radios and the Beatles repaid the compliment by presenting him with their own enormous brush painting, with each of the four sections signed by the Beatles painter.

Other suite pastimes included watching late-night French movies on TV with dubbed Japanese dialogue, photographing each other with new equipment, sampling semi-Japanese dishes hidden away quietly on the Americanised Hilton Hotel menu!

The Beatles impressed politely enthusiastic fans by elaborately courteous Japanese etiquette, but they were disappointed that they were unable to take extended sightseeing trips and unable to meet more fans.

AFTER A FANTASTIC FIRST TRIP TO THE FAR EAST, THE BEATLES WERE STARTING THEIR HOMEWARD JOURNEY ON TUESDAY VIA HONG KONG.

From Disc And Music Echo – July 9, 1966

HONOURABLE JAPANESE

The Beatles experienced a completely different set-up in Japan from any other country they have visited. In the first place, the Japanese authorities considered it their responsibility to look after the boys, and if anything had gone wrong, they would have considered it a great dishonour to themselves. Also the Beatles had heard that Japanese audiences were much wilder, but, in actual fact, they were more restrained, especially while the boys were singing. This might have been due to the fact that the 9,000 audience in the Budo Kan had 3,000 police to look after them!!!

From The Beatles Monthly Book – August 1966

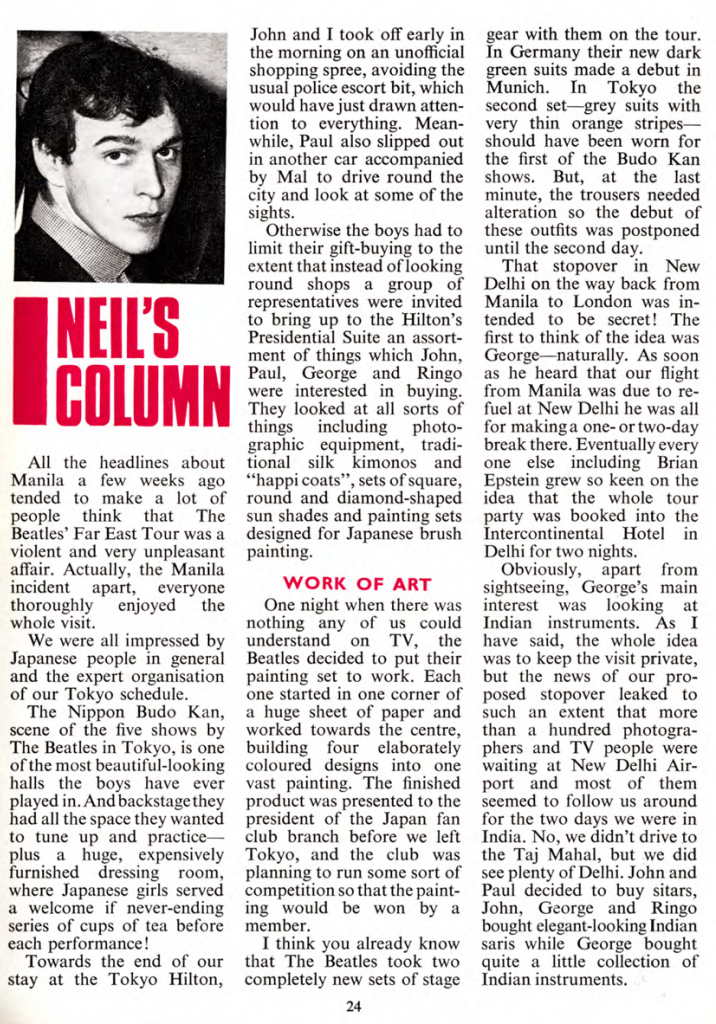

NEIL’S COLUMN

All the headlines about Manila a few weeks ago tended to make a lot of people think that The Beatles’ Far East Tour was a violent and very unpleasant affair. Actually, the Manila incident apart, everyone thoroughly enjoyed the whole visit.

We were all impressed by Japanese people in general and the expert organisation of our Tokyo schedule.

The Nippon Budo Kan, scene of the five shows by The Beatles in Tokyo, is one of the most beautiful-looking halls the boys have ever played in. And backstage they had all the space they wanted to tune up and practice — plus a huge, expensively furnished dressing room, where Japanese girls served a welcome if never-ending series of cups of tea before each performance!

Towards the end of our stay at the Tokyo Hilton, John and I took off early in the morning on an unofficial shopping spree, avoiding the usual police escort bit, which would have just drawn attention to everything. Meanwhile, Paul also slipped out in another car accompanied by Mal to drive round the city and look at some of the sights.

Otherwise the boys had to limit their gift-buying to the extent that instead of looking round shops a group of representatives were invited to bring up to the Hilton’s Presidential Suite an assortment of things which John, Paul, George and Ringo were interested in buying. They looked at all sorts of things including photographic equipment, traditional silk kimonos and “happi coats”, sets of square, round and diamond-shaped sun shades and painting sets designed for Japanese brush painting.

WORK OF ART

One night when there was nothing any of us could understand on TV, the Beatles decided to put their painting set to work. Each one started in one corner of a huge sheet of paper and worked towards the centre, building four elaborately coloured designs into one vast painting. The finished product was presented to the president of the Japan fan club branch before we left Tokyo, and the club was planning to run some sort of competition so that the painting would be won by a member.

I think you already know that The Beatles took two completely new sets of stage gear with them on the tour. In Germany their new dark green suits made a debut in Munich. In Tokyo the second set — grey suits with very thin orange stripes — should have been worn for the first of the Budo Kan shows. But, at the last minute, the trousers needed alteration so the debut of these outfits was postponed until the second day.

That stopover in New Delhi on the way back from Manila to London was intended to be secret! The first to think of the idea was George — naturally. As soon as he heard that our flight from Manila was due to refuel at New Delhi he was all for making a one- or two-day break there. Eventually, every one else including Brian Epstein grew so keen on the idea that the whole tour party was booked into the Intercontinental Hotel in Delhi for two nights.

Obviously, apart from sightseeing, George’s main interest was looking at Indian instruments. As I have said, the whole idea was to keep the visit private, but the news of our proposed stopover leaked to such an extent that more than a hundred photographers and TV people were waiting at New Delhi Airport and most of them seemed to follow us around for the two days we were in India. No, we didn’t drive to the Taj Mahal, but we did see plenty of Delhi. John and Paul decided to buy sitars, John, George and Ringo bought elegant-looking Indian saris while George bought quite a little collection of Indian instruments.

From The Beatles Monthly Book – August 1966

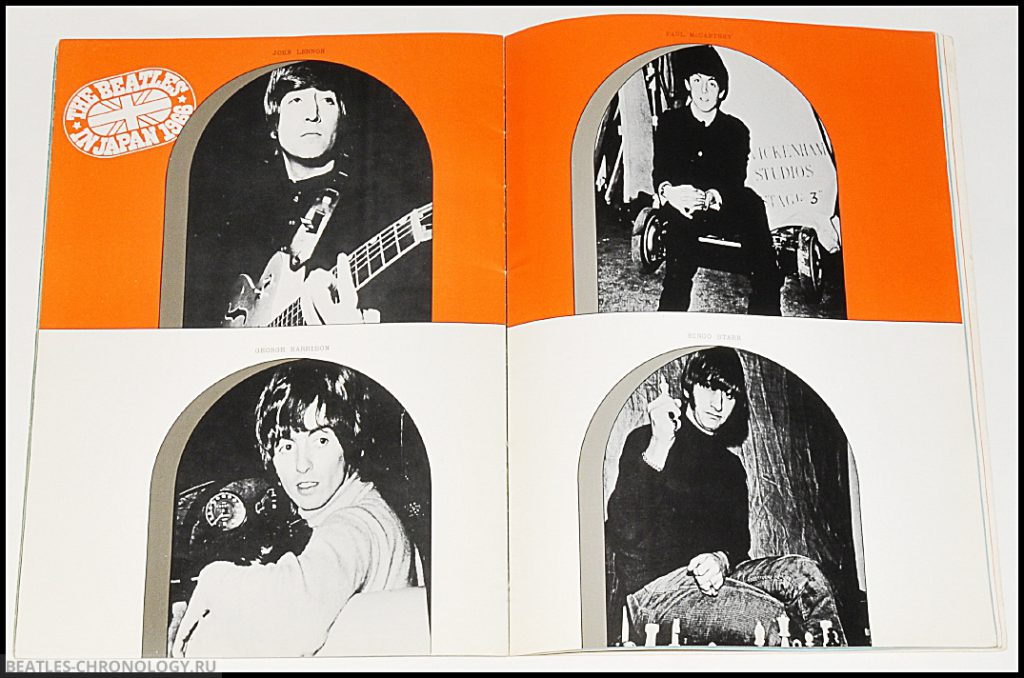

Japan • Tokyo • Nippon Budokan

Jun 30, 1966 • There are 3 albums covering this show

Japan • Tokyo • Nippon Budokan • 2pm show

Jul 01, 1966 • There is 1 album covering this show

Japan • Tokyo • Nippon Budokan • 6:30pm show

Jul 01, 1966

Japan • Tokyo • Nippon Budokan • 2pm show

Jul 02, 1966

Japan • Tokyo • Nippon Budokan • 6:30pm show

Jul 02, 1966

Philippines • Manila • Rizal Memorial Football Stadium • 4pm show

Jul 04, 1966

Philippines • Manila • Rizal Memorial Football Stadium • 8:30pm show

Jul 04, 1966

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.