June 18 and June 20, 1966

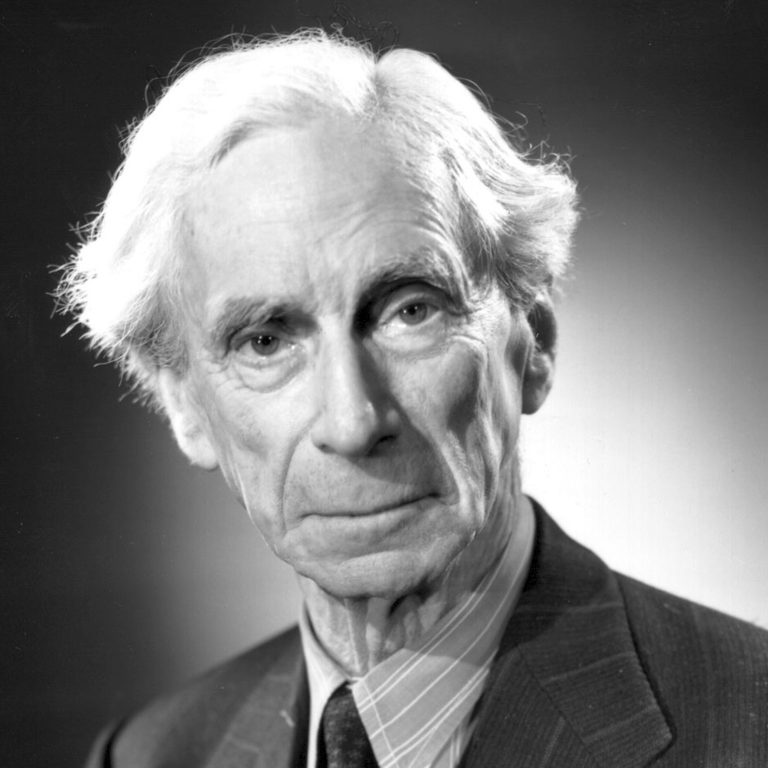

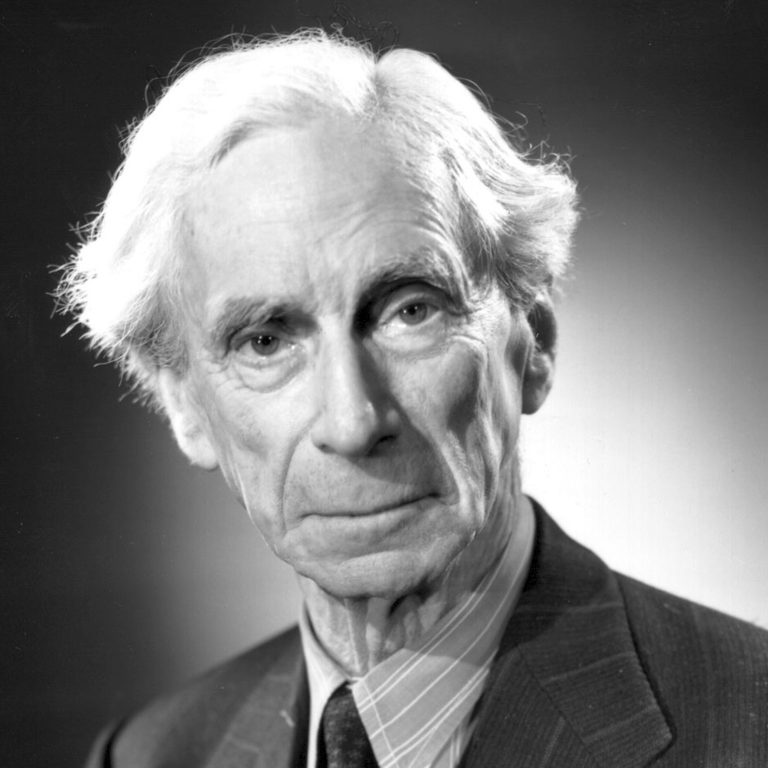

Paul McCartney discusses the Vietnam War with Bertrand Russell

Last updated on November 26, 2023

June 18 and June 20, 1966

Last updated on November 26, 2023

Location: Bertrand Russell's home, Hasker Street, London, UK

Previous article Jun 17, 1966 • Paul McCartney buys High Park Farm in Kintyre, Scotland

Session Jun 17, 1966 • Recording and mixing "Here, There And Everywhere", "Got To Get You Into My Life"

Interview Jun 17, 1966 • George Martin interview for New Musical Express

Article June 18 and June 20, 1966 • Paul McCartney discusses the Vietnam War with Bertrand Russell

Interview Jun 18, 1966 • Paul McCartney interview for Disc And Music Echo

Interview Jun 18, 1966 • Paul McCartney interview for Melody Maker

Next article June 19, 1966 ? • Paul and Jane watch "Midsummer Night's Dream"

On June 18, 1966, Paul McCartney celebrated his 24th birthday. On this day, he visited philosopher Bertrand Russell at his London home along with his partner, Jane Asher. He visited again on June 20.

Russell was a renowned pacifist and vocal critic of America’s policy in Southeast Asia, particularly the Vietnam War, which the US had been involved in since 1963. At the time of the visit, Russell was 94 years old.

It seems that this encounter with Russell was the first time Paul became aware of the tragedy of the war. Paul claimed that he made The Beatles aware of the situation afterwards: “I said to the guys ‘Hey, I met Bertrand Russell and he’s really against this war.’ So I explained to everyone the issue.”

A few weeks after those visits, The Beatles began their last tour in the US. However, the tour was plagued with backlash regarding the controversy of John Lennon’s remark about the Beatles being “more popular than Jesus.” During the press conferences, the Beatles speaking out against the Vietnam War added further controversy to the visit.

From Wikipedia:

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, OM, FRS (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, artificial intelligence, cognitive science, computer science, and various areas of analytic philosophy, especially philosophy of mathematics, philosophy of language, epistemology, and metaphysics. […]

Russell spent the 1950s and 1960s engaged in political causes primarily related to nuclear disarmament and opposing the Vietnam War. The 1955 Russell–Einstein Manifesto was a document calling for nuclear disarmament and was signed by eleven of the most prominent nuclear physicists and intellectuals of the time. In October 1960 “The Committee of 100” was formed with a declaration by Russell and Michael Scott, entitled “Act or Perish”, which called for a “movement of nonviolent resistance to nuclear war and weapons of mass destruction”. In September 1961, at the age of 89, Russell was jailed for seven days in Brixton Prison for a “breach of the peace” after taking part in an anti-nuclear demonstration in London. The magistrate offered to exempt him from jail if he pledged himself to “good behaviour”, to which Russell replied: “No, I won’t.”

In 1966–1967, Russell worked with Jean-Paul Sartre and many other intellectual figures to form the Russell Vietnam War Crimes Tribunal to investigate the conduct of the United States in Vietnam. He wrote a great many letters to world leaders during this period. […]

Just when we were getting to be well-known someone said to me, “Bertrand Russell is living not far from here in Chelsea why don’t you go and see him?” and so I just took a taxi down there and knocked on the door. There was an American guy who was helping him and he came to the door and I said, “I’d like to meet Mr Russell, if possible.” I waited a little and then met the great man and he was fabulous. He told me about the Vietnam war—most of us didn’t know about it, it wasn’t yet in the papers—and also that it was a very bad war. I remember going back to the studio either that evening or the next day and telling the guys, particularly John [Lennon], about this meeting and saying what a bad war this was. We started to investigate and American pals who were visiting London would be talking about being drafted. Then we went to America, and I remember our publicist—he was a fat, cigar-chomping guy, saying, “Whatever you do, don’t talk about Vietnam.” Of course, that was the wrong thing to say to us. You don’t tell rebellious young men not to say something. So of course we talked about it the whole time and said it was a very bad war. Obviously, we backed the peace movement.

Paul McCartney – Interview with Prospect, January 2009

The whole anti-war thing has been quite a big thing since the sixties. In my case, it started when I met Bertrand Russell, who was already in his nineties, in London. This was, I think, around 1964, and he was staying somewhere in Chelsea – on Flood Street, maybe – and a friend of a friend said, ‘You should go and meet him.’ I’d seen him on TV and thought he was an interesting speaker. I’d read a few things by him too and had always been impressed by his dignity and how well he put across an idea. So I went along and knocked on the door, and an American student – his assistant or something – came to the door, and I said, ‘Oh, hi. Could I meet Mr Russell?’ I went just on the off chance, which was how we used to do it. This was the sixties, remember – the freewheeling sixties – when you didn’t have to make an appointment or ask someone permission to call them on the telephone. So, even to this day, I’ll think, ‘Well, if he’s in, fine, and if he wants to meet me, if he can spare five minutes, great, and if he wants to go longer, also great.’

Anyway, I went in and met Bertrand Russell, and we talked. At the time he was focusing his energies on the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation, which he’d set up the year before, and campaigning against the war in Vietnam. He was the first person to tell me about what had been going on in Vietnam, and he explained that it was an imperialist war supported by vested interests. None of us really knew about this at that point. You have to realise, this was still quite early in the war, before the protests really started.

Paul McCartney – From “The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present“, 2021

So, I remember going back to the recording studio and telling John about it, and again, he hadn’t known there was a war going on in Vietnam either. But I think that was the start of our being more aware of what wars people were involved in, and politics started to become a more regular topic of discussion in the band and amongst our friends and the people we were hanging out with.

Paul McCartney – From “The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present“, 2021

Now in his nineties, Russell remained a prominent cultural commenter and was the only living British philosopher that most British people knew of. When Paul discovered that Russell had a London house on Hasker Street, only three streets away from the apartment shared by John Dunbar and Marianne Faithfull, he made an appointment to meet him when the great man made one of his infrequent visits south from his home at Penrhyndeudraeth in North Wales.

Russell’s thirty-year-old American assistant, Ralph Schoenman, a formidable antiwar campaigner in his own right and an original signatory of the Committee of 100, which promoted civil disobedience in the cause of peace, had known Paul since 1964 and was instrumental in setting up this meeting between the author of “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and “Can’t Buy Me Love” and the author of A History of Western Philosophy and Has Man a Future? He recalls Paul’s nervousness on the day: “He was rather self-conscious during the conversation and at one point gestured awkwardly, his arm causing the lamp to the left of his chair to go flying. Russell was gracious, put Paul at his ease and the conversation resumed seamlessly.”

It was Russell’s involvement in the peace movement rather than his humanistic philosophy that interested Paul. Almost forty years later Paul would claim that it was Russell who made him aware of what was taking place in Vietnam and that later that day, at EMI Studios: “I said to the guys ‘Hey, I met Bertrand Russell and he’s really against this war.’ So I explained to everyone the issue.”

From “Beatles ’66: The Revolutionary Year” by Steve Turner

Jane Asher and Paul McCartney visited Bertrand Russell twice in 1966, on Saturday 18 June and the following Monday. This is according to Edith Russell’s appointment diary in which she recorded their arrival at 4pm and, on the Monday, that they stayed ‘till 6.30!’ Evidently, this was an extended teatime with their young visitors. Paul was celebrating his 24th birthday on 18 June.

McCartney recalls his meeting with Russell in his bestselling book, The Lyrics, published in 2021. ‘I’d read a few things by him’ he writes, ‘and had always been impressed by his dignity and how well he put across an idea.’ ‘A friend of a friend’ had given McCartney Russell’s address in Hasker Street, Chelsea, and he went and knocked on the door. This was the ‘freewheeling sixties’ when you could apparently do such a thing. Paul and Jane were invited in and McCartney recounts how Russell was the ‘first person to tell me about what was going on in Vietnam’, whilst describing what the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation was doing. ‘He explained that it was an imperialist war supported by vested interests.’ After tea, McCartney recalls going back to the recording studio and telling John Lennon and the others about what Russell had said. […]

‘A lot of us had friends who were going to Vietnam – or were trying to avoid going to Vietnam’ says Paul. ‘It was our age group, our peer group; the fact that Americans of our age group were going there brought it home to us.’

In a recent interview, McCartney mentioned how The Beatles were touring in Britain when they heard that President Kennedy had been murdered in Dallas, on 22 November 1963. Those of us alive then well remember the sombre news — the BBC played Chopin’s Funeral March instead of broadcasting its scheduled programmes. In 1966, Mark Lane, the US lawyer who challenged the findings of the official Warren Report on the President’s murder, came to London to finish Rush to Judgment, his bestselling book about the assassination, which was published in August that year. Was Mark Lane the ‘friend of a friend’ who passed on Russell’s Chelsea address to Paul? Lane had apparently met McCartney at a party in London. Documentary filmmaker Emile de Antonio collaborated with Lane in translating Rush to Judgment to the cinema screen, which can now be found on YouTube. There was talk that Paul might write some music for the film, which noticeably has none. […]

Tony Simpson – From Spokesman the publishing imprint of the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation

Beatles press conference in Tokyo, June 29, 1966:

Q: “How much interest do you take in the war that is going on in Vietnam now?”

JOHN: “Well, we think about it everyday, and we don’t agree with it and we think it’s wrong. That’s how much interest we take. That’s all we can do about it… and say that we don’t like it.”

Beatles press conference in Toronto, August 17, 1966:

Q: “John, I don’t want to get you too tangled in politics, but I read that you weren’t very excited about the situation in Vietnam. I would be interested in knowing your opinion, or any of the Beatles opinion, about the question of the United States involvement in Vietnam and whether or not you see this as a possibility of a world confrontation with China, and whether you think it’s dangerous, and whether you think it’s important for people to become informed and concerned on this issue.”

JOHN: “Yes.”

(laughter)

JOHN: “I mean, we all just don’t agree with war for any reason whatsoever. There’s no reason on earth why anybody should kill anybody else.”

Q: “Well, why don’t you say… Why don’t you come out and…”

GEORGE: “The main thing is…”

JOHN: “Because somebody would shoot us for saying it, that’s why.”

GEORGE: “Somebody once said ‘Thou shalt not kill means THAT, not amend section A.’ And there’s a lot of people who are amending section A and who are killing. And it’s up to them to sort themselves out.”

PAUL: “But we can’t say things like that.”

JOHN: “We’re not allowed to have opinions. You might have noticed, you know.”

(laughter)

Q: “Continuing in that line, what do you think of the youthful Americans who are coming across the border to Canada to escape the draft? Are you in favor of the draft or military disipline for the younger generation?”

PAUL: “No.”

GEORGE: “I think anybody who doesn’t feel like fighting or feels like fighting is wrong has a right not to go in the army. There’s nobody can force you into going and killing someone.”

JOHN: “But they do.”

PAUL: “Shouldn’t be able to, really.”

JOHN: (sighs, and continues jokingly) “Ahh, we’ve had it in Memphis now.”

Beatles press conference in Memphis, August 19, 1966:

Q: “But do you mind being asked questions, for example in America people keep asking you questions about Vietnam. Does this seem useful?”

PAUL: “Well, I dunno, you know. If you can say that war is no good, and a few people believe you, then it may be good. I don’t know. You can’t say too much, though. That’s the trouble.”

JOHN: “It seems a bit silly to be in America and for none of them to mention Vietnam as if nothing was happening.”

Q: “But why should they ask you about it? You’re successful entertainers.”

JOHN: “Because Americans always ask showbiz people what they think, and so do the British. (comically) Showbiz… you know how it is!”

RINGO: (laughs)

JOHN: “But I mean you just gotta… You can’t keep quiet about anything that’s going on in the world, unless you’re a monk. (jokingly, with dramatic arm gestures) Sorry, monks! I didn’t mean it! I meant actually….”

(Beatles laugh)

Beatles press conference in New York, August 22, 1966:

Q: “Would any of you care to comment on any aspect of the war in Vietnam?”

JOHN: “We don’t like it.”

Q: “Could you elaborate any?”

JOHN: “No. I’ve elaborated enough, you know. We just don’t like it. We don’t like war.”

GEORGE: “It’s, you know… It’s just war is wrong, and it’s obvious it’s wrong. And that’s all that needs to be said about it.”

(applause)

PAUL: “We can elaborate in England.” […]

Q: “One of you, I believe it was George, said that you couldn’t comment on Vietnam in this country but you could in England. Could you elaborate on that a little bit?”

GEORGE: “I didn’t say that. Maybe one of us said that, but I didn’t.”

PAUL: “It was me. I mean, you know about that, anyway, you know. I mean, we could say a thing about… like John’s religious thing in England and it wouldn’t be taken up and misinterpreted quite as much as it tends to get here. I mean, you know it does. The thing is that, I think you can say things like that in England and people will listen a bit more than they do in America, because in America somebody will take it up and use it completely against you and won’t have many scruples about doing that. You know, I’m probably putting my foot in it saying that, but…”

JOHN: “You’ll be explaining to the next bunch.”

PAUL: “Yeah, I know.”

(laughter)

PAUL: (jokingly, in American accent) “Oh well, it’s just wonderful here.”

(laughter)

The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years

"With greatly expanded text, this is the most revealing and frank personal 30-year chronicle of the group ever written. Insider Barry Miles covers the Beatles story from childhood to the break-up of the group."

We owe a lot to Barry Miles for the creation of those pages, but you really have to buy this book to get all the details - a day to day chronology of what happened to the four Beatles during the Beatles years!

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.