March 2012

Interview for MOJO

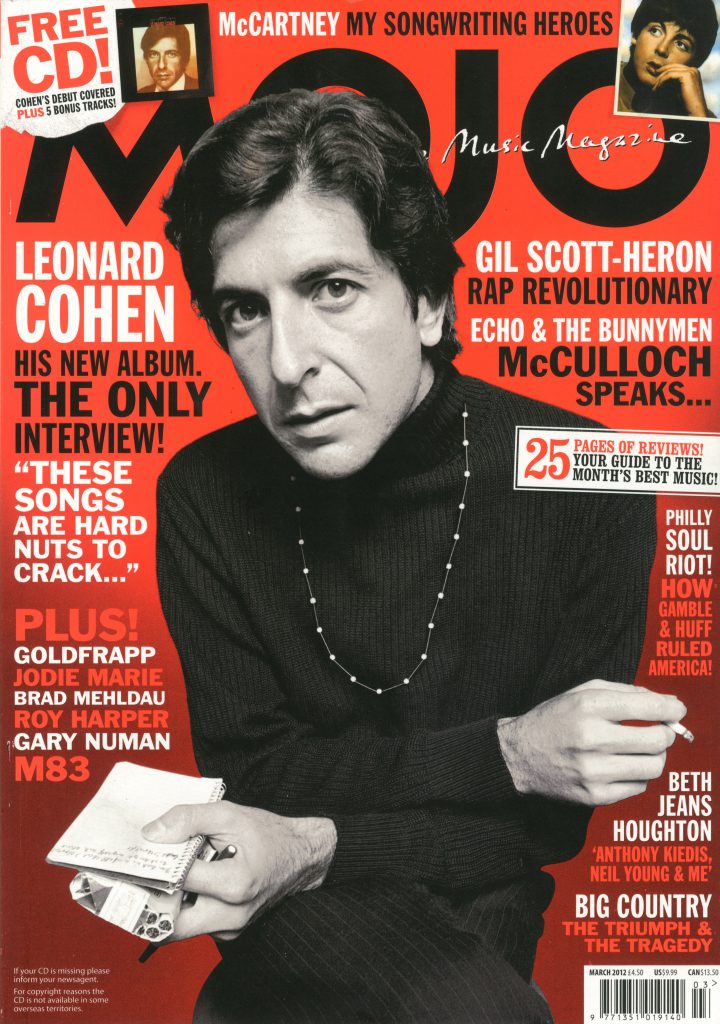

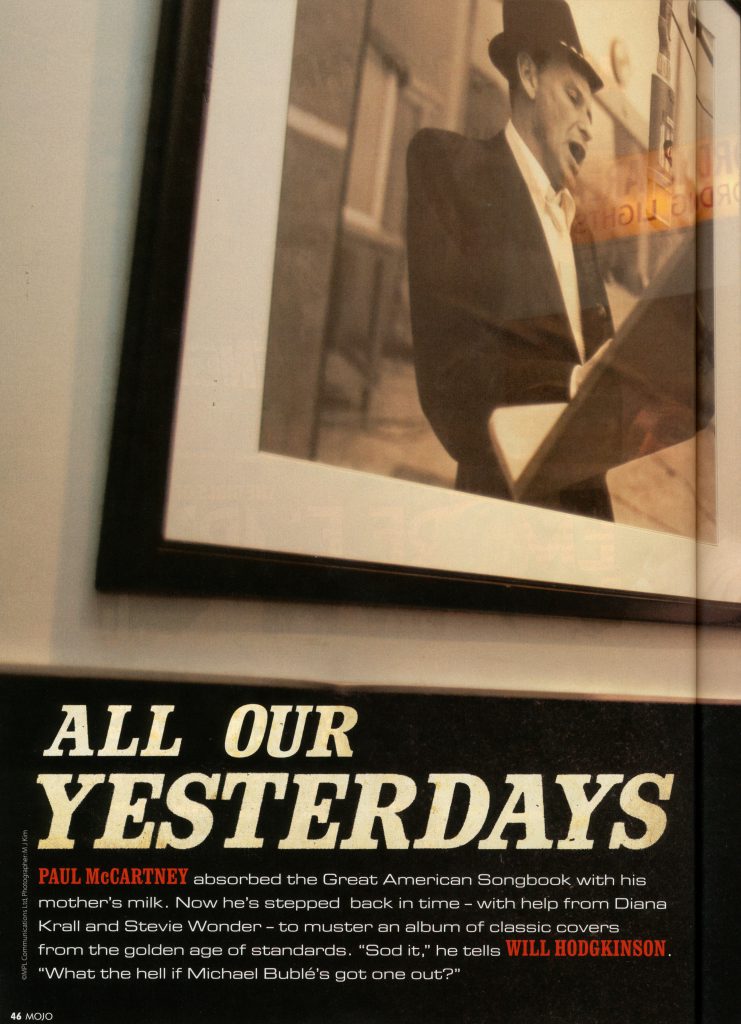

All Our Yesterdays

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Last updated on August 20, 2023

March 2012

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Last updated on August 20, 2023

Interview location: The Hartwall Arena, Helsinki, Finland

Article Feb 29, 2012 • Paul McCartney's childhood home given Grade II listed status

Interview March 2012 • Paul McCartney interview for RollingStone

Interview March 2012 • Paul McCartney interview for MOJO

Live album Mar 06, 2012 • "iTunes Live from Capitol Studios" by Paul McCartney released globally

Concert Mar 24, 2012 • Netherlands • Rotterdam

Next interview Mar 29, 2012 • Paul McCartney interview for NPR Music

AlbumThis interview was made to promote the "Kisses On the Bottom" Official album.

Helsinki • The Hartwall Arena • Finland

Dec 12, 2011 • Finland • Helsinki • The Hartwall Arena

Officially appears on Revolver (UK Mono)

Officially appears on Please Please Me (Mono)

I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter

Officially appears on Kisses On the Bottom

Officially appears on Kisses On the Bottom

Officially appears on Kisses On the Bottom

My Very Good Friend The Milkman

Officially appears on Kisses On the Bottom

Officially appears on Kisses On the Bottom

This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

AT THE HARTWALL ARENA IN HELSINKI, the soundcheck for Paul McCartney’s concert was scheduled to start an hour ago. McCartney, however, flew in late the night before, held up in Sweden as a storm raged across the border. Rumour has it he’s having a lie-in.

Finnish official types dart about, walkie-talkies buzzing with updates on McCartney’s movements. Then he arrives, runs through a soundcheck before a handful of fans and, after an hour’s break, performs a three-hour set of songs that have become the standards of post-war pop: Yesterday, Blackbird, The Long And Winding Road included among compositions that are known and sung the world over.

Before getting his world tour up and running, McCartney found time to record Kisses On The Bottom, an album of standards from another age. As anyone who’s tried learning them on guitar knows, Beatles songs tend to be easy to listen to and hard to play, a quality they share with Kisses… ‘The Glory Of Love’ and ‘My Very Good Friend The Milkman’. These melodically rich, structurally ingenious classics from Tin Pan Alley’s ’20s/’30s golden age brought jazz invention and classical sophistication to popular music for the first time. Songwriters like George Gershwin, Irving Berlin and Harold Arlen, most of them from impoverished, New York, Jewish émigré families, combined uptown aspiration with downtown attitude, setting the blueprint for the modern pop song in the process. And they had as much of an influence on Lennon & McCartney as Chuck Berry or The Everly Brothers did. Listen to Ahlert & Young’s I’m Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter and follow it with When I’m Sixty-Four, which McCartney wrote when he was 16, and the influence is laid bare.

McCartney describes Kisses… as “get home from work music; you put it on and have a glass of wine.” MOJO found that the album, which brings a lighter-than-air, hazy feel to such elegant gems as Frank Loesser’s Inchworm and Arlen and Yip Harburg’s It’s Only A Paper Moon, reflects a relaxant of the more smokeable variety. But it could be that My Valentine’s woozy mood simply reflects its 9-year-old singer’s state of contentment.

IN THAT NARROW WINDOW BETWEEN SOUNDCHECK and stage time, MOJO is led down myriad backstage pathways to a candlelit space that turns out to be McCartney’s dressing room. Nancy Shevell, his wife since October 2011, is sitting on a sofa, looking serene; opposite her is McCartney. Introductions are made. Shevell glides into another room. “Help yourself,” says McCartney, gesturing at bowls of cashew nuts and chocolate raisins, before MOJO asks: Why, at this point in his career, did he choose to record an album of standards?

“Actually,” he begins, masticating a cashew nut/chocolate raisin amalgam, “I’ve been wanting to do it for a long time. But every time I shaped up to it someone else would come along and do the same thing. Rod Stewart was doing them, and before him, there was Robbie Williams… In the end, I thought, Sod it. What the hell if Michael Bublé’s got one out?”

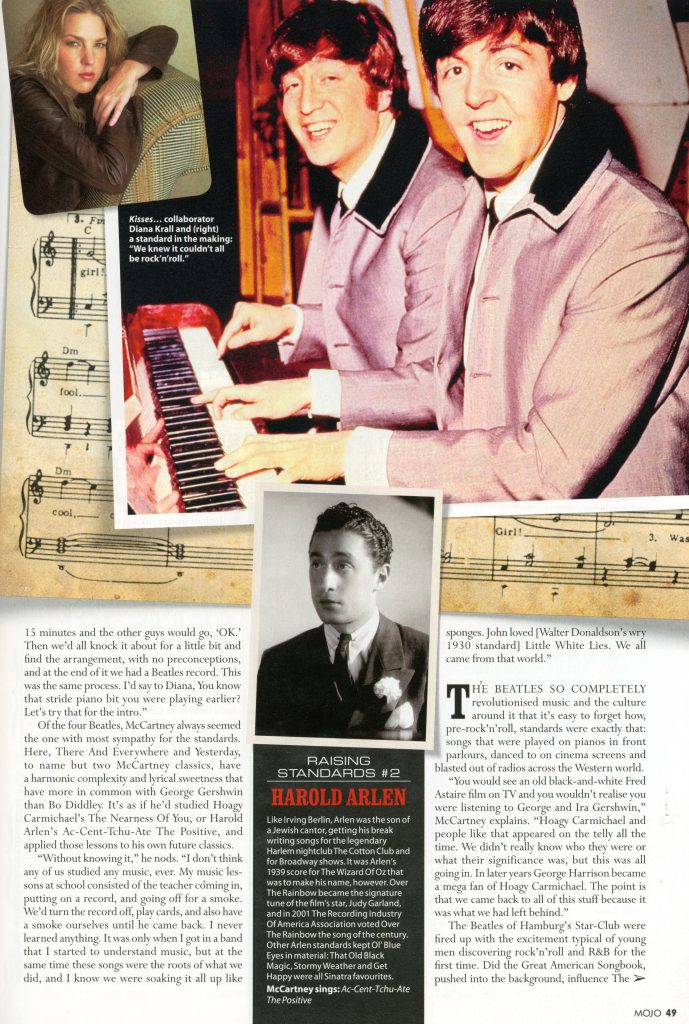

The style of the material led McCartney to Tommy LiPuma, a Cleveland, Ohio-born producer of the old school. A former jazz saxophonist who grew up on the music of Stan Getz and Zoot Sims, LiPuma was a staff producer for Herb Alpert’s A&M Records in the ’60s and Warners in the ’70s, straddling the easy-listening/jazz divide on albums for The Sandpipers, Barbra Streisand, Miles Davis and, more recently, Diana Krall. The latter became McCartney’s musical partner on My Valentine, while guests include Eric Clapton (guitar on the title track) and Macca’s old Ebony And Ivory oppo Stevie Wonder, who dug out his chromatic harmonica on Only Our Hearts.

“Once I was happy about making the album with Tommy I let him make a lot of the decisions because it’s not really my world,” he explains. “He suggested Diana. I met her, she’s cool, she loves all these songs, she likes what I do and she was happy to be an accompanist. So it became a project.”

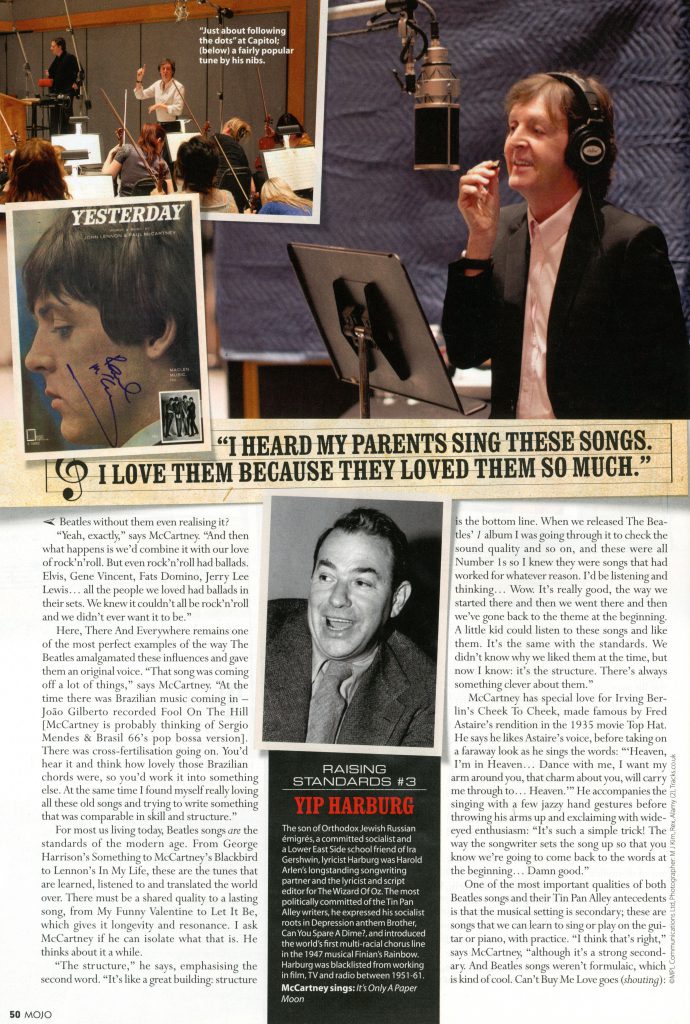

Working with highly trained jazz musicians on songs that are generally played from sheet music put McCartney in a vulnerable position.

“I don’t read or write music. Here I am with these great players, and it’s kind of embarrassing. These standards are not usually improvised at all.”

How was the situation resolved?

“We took some time over the songs, and I realised that they had rambling verses before they got to the choruses. So the verse is going, ‘I was walking down the street, I was having a cup of tea with the vicar…’ and I’m just about following the dots on the page, like I’m in an exam. By the time I had it together the other guys had decided on where the solo was coming in and so on, so the whole thing became organic and improvised. And the thing is: it reminded me of how The Beatles used to work.”

In The Beatles, McCartney and Lennon would bring in a song, never written down in chart form, to the other members of the band.

“George and Ringo wouldn’t know the song because we had only written it two days before; George Martin wouldn’t know it, so it was a fresh little thing,” says McCartney. “We’d play it for 10 or 15 minutes and the other guys would go, ‘OK.’ Then we’d all knock it about for a little bit and find the arrangement, with no preconceptions, and at the end of it we had a Beatles record. This was the same process. I’d say to Diana, You know that stride piano bit you were playing earlier? Let’s try that for the intro. “

Of the four Beatles, McCartney always seemed the one with most sympathy for the standards. Here, There And Everywhere and Yesterday, to name but two McCartney classics, have a harmonic complexity and lyrical sweetness that have more in common with George Gershwin than Bo Diddley. It’s as if he’d studied Hoagy Carmichael’s The Nearness Of You, or Harold Arlen’s Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate The Positive, and applied those lessons to his own future classics.

“Without knowing it,” he nods. “I don’t think any of us studied any music, ever. My music lessons at school consisted of the teacher coming in, putting on a record, and going off for a smoke. We’d turn the record off, play cards, and also have a smoke ourselves until he came back. I never learned anything. It was only when I got in a band that I started to understand music, but at the same time these songs were the roots of what we did, and I know we were soaking it all up like sponges. John loved [Walter Donaldson’s wry 1930 standard] Little White Lies. We all came from that world.”

THE BEATLES SO COMPLETELY revolutionised music and the culture pre-rock’n’roll, standards were exactly that: songs that were played on pianos in front parlours, danced to on cinema screens and blasted out of radios across the Western world.

“You would see an old black-and-white Fred Astaire film on TV and you wouldn’t realise you were listening to George and Ira Gershwin,” McCartney explains. “Hoagy Carmichael and people like that appeared on the telly all the time. We didn’t really know who they were or what their significance was, but this was all going in. In later years George Harrison became a mega fan of Hoagy Carmichael. The point is that we came back to all of this stuff because it was what we had left behind.”

The Beatles of Hamburg’s Star-Club were fired up with the excitement typical of young men discovering rock’n’roll and R&B for the first time. Did the Great American Songbook, pushed into the background, influence The Beatles without them even realising it?

“Yeah, exactly,” says McCartney. “And then what happens is we’d combine it with our love of rock’n’roll. But even rock’n’roll had ballads. Elvis, Gene Vincent, Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis… all the people we loved had ballads in their sets. We knew it couldn’t all be rock’n’roll and we didn’t ever want it to be.”

Here, There And Everywhere remains one of the most perfect examples of the way The Beatles amalgamated these influences and gave them an original voice.

“That song was coming off a lot of things,” says McCartney. “At the time there was Brazilian music coming in – João Gilberto recorded Fool On The Hill [McCartney is probably thinking of Sergio Mendes & Brasil 66’s pop bossa version]. There was cross-fertilisation going on. You’d hear it and think how lovely those Brazilian chords were, so you’d work it into something else. At the same time, I found myself really loving all these old songs and trying to write something that was comparable in skill and structure.”

For most us living today, Beatles songs are the standards of the modern age. From George Harrison’s Something to McCartney’s Blackbird to Lennon’s In My Life, these are the tunes that are learned, listened to and translated the world over. There must be a shared quality to a lasting song, from My Funny Valentine to Let It Be, which gives it longevity and resonance. I ask McCartney if he can isolate what that is. He thinks about it a while.

“The structure,” he says, emphasising the second word. “It’s like a great building: structure is the bottom line. When we released The Beatles’ 1 album I was going through it to check the sound quality and so on, and these were all Number 1s so I knew they were songs that had worked for whatever reason. I’d be listening and thinking… Wow. It’s really good, the way we started there and then we went there and then we’ve gone back to the theme at the beginning. A little kid could listen to these songs and like them. It’s the same with the standards. We didn’t know why we liked them at the time, but now I know: it’s the structure. There’s always something clever about them.”

McCartney has special love for Irving Berlin’s Cheek To Cheek, made famous by Fred Astaire’s rendition in the 1935 movie Top Hat. He says he likes Astaire’s voice, before taking on a faraway look as he sings the words: “’Heaven, I’m in Heaven… Dance with me, I want my arm around you, that charm about you, will carry me through to… Heaven.’” He accompanies the singing with a few jazzy hand gestures before throwing his arms up and exclaiming with wide-eyed enthusiasm: “It’s such a simple trick! The way the songwriter sets the song up so that you know we’re going to come back to the words at the beginning… Damn good.“

One of the most important qualities of both Beatles songs and their Tin Pan Alley antecedents is that the musical setting is secondary; these are songs that we can learn to sing or play on the guitar or piano, with practice.

“I think that’s right,” says McCartney, “although it’s a strong secondary. And Beatles songs weren’t formulaic, which is kind of cool. Can’t Buy Me Love goes (shouting): ‘CAN’T BUY ME LOVE!’ Bang! It screams at you and then it settles down, which is unusual.”

FOR GENERATIONS, SONGWRITERS have dissected and analysed Beatles songs in an attempt to identify what makes them so magical. Listening to McCartney explain how they came up with them, it’s clear he’s not sure himself.

“I think we knew inherently that we wanted to get good structure, but I do often wonder: how did we know about that, so instinctively? I think what really helped was listening to a lot of good music. You’ve got to have something that will stand up and not get blown over, and then you can decorate it. Look at Sydney Opera House. You see how odd a cool structure can be. So we went: ‘OK. Motown looks like that. Elvis is doing that. Little Richard is doing that. Let’s do…” and McCartney holds his palms out: “this.”

The pre-rock songwriters were, meanwhile, “right there in the back room” and McCartney took lyrical inspiration from their wit, and their knowing take on romance.

“Having known what we knew,” he says, “and listened to what we listened to as kids, I don’t think it would have been likely for us to start writing songs like (puts on a voice suggesting subnormal intelligence); “’I love you. Yes that’s true. What can I do? I love you.’ We would just laugh at each other. And the great thing for me was having John as a partner, because if we did crap we’d knock it down. You know, ‘You can’t say that.’ ‘Why not?” ‘Because it’s shit.’ So you find another way round it. That happened all the time. With I Saw Her Standing There I brought the line: ‘She was just 17/She’d never been a beauty queen.’ And John went: ‘Oh… ‘I’d look at him and say, Yeah, you’re right. “Better think of something else…”

Things could have been so different…

“We both knew that the line was wrong. So you end up with, ‘She was just 17, you know what I mean, which is much more significant, even though it’s simpler. With the show I’m doing tonight I get to look at our old numbers, just as I got to look at [the standards] with the album. I had heard my parents, my uncles and aunties sing them, and I love them partly because of that – because they loved them so much. I have reflected love for them.”

Before McCartney goes out to perform a three hour set that sends 15,000 Finnish fans bananas, I ask if he can look at his songs, now over 40 years old, and appreciate them in the same objective way he can appreciate the standards.

“I really do,” he says. “I think: that boy was a good writer. I’m singing it, my mind wanders, and I’m going: how old was I when I wrote this? Not bad. Like in Yesterday: ‘I’m not half the man I used to be.’ I was writing that at 24? People do that, though. A lot of people who do well do their best work in their twenties.”

McCartney is about to be led towards the stage. There’s just enough time to stand up, shake hands, and say that it’s the wisdom in those Beatles ballads that makes them remarkable, considering – we dare to suggest – that we don’t know much about life at 24.

“You didn’t grow up in Liverpool,” says McCartney. Then, just before launching into set-starter Hello Goodbye, he sums up his songwriting education in four words: “School of hard knocks.“

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.