March 2012

Interview for RollingStone

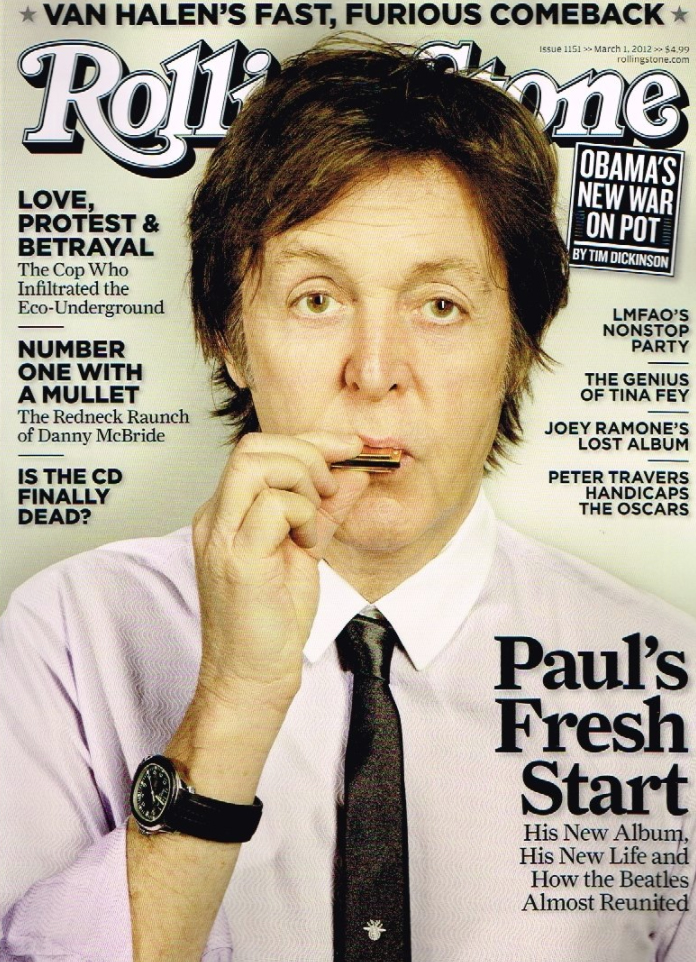

Paul's Fresh Start

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

March 2012

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Previous interview Feb 18, 2012 • Paul McCartney interview for Billboard

Article Feb 29, 2012 • Paul McCartney's childhood home given Grade II listed status

Interview March 2012 • Paul McCartney interview for RollingStone

Interview March 2012 • Paul McCartney interview for MOJO

Live album Mar 06, 2012 • "iTunes Live from Capitol Studios" by Paul McCartney released globally

AlbumThis interview was made to promote the "Kisses On the Bottom" Official album.

Officially appears on The Beatles (Mono)

Officially appears on Revolver (UK Mono)

Officially appears on Abbey Road

Officially appears on Kisses On the Bottom

Officially appears on Help! (Mono)

The interview below has been reproduced from this page. This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

Read interview on RollingStone

On his way to work this morning, Paul McCartney had to wait for some pedestrians at a white-striped crosswalk. They stood in groups, cameras in hand, blocking a tree-lined London street. As McCartney sat patiently in his SUV, none of them looked his way – the tourists were too busy taking pictures of themselves crossing Abbey Road.

“It’s happened to me a few times,” McCartney says later, with a small laugh. “It’s a moment I quite enjoy. There’s a good, strong metaphor there. But there’s so many metaphors in my life – I don’t look for them. The life of a Beatle is full of metaphors.”

Resisting an urge to jump out of the car and pose with his fans, he instead heads straight onto hallowed, if distinctly musty-smelling, ground: Abbey Road’s Studio Two. “Welcome to my world,” McCartney says, striding through double doors at the back of a high-ceilinged, rectangular, gymnasiumlike room. He’s chomping on a piece of gum. “Ancient and modern. Every time I come in here, I unravel the whole story again. This is where it all happened.”

The Beatles recorded most of their music, from “Love Me Do” to “The End,” in this unglamorous, white-walled basement space – and passed their initial EMI audition here almost exactly 50 years ago. Aside from some newish acoustic baffles and a different clock, it’s hardly changed. In one corner, McCartney yelped, “One, two, three, faw!” to start “I Saw Her Standing There”; in another, he slammed an E-major chord on one of the many pianos heard at the end of “A Day in the Life.”

Right now, for no particular reason, he’s playing drums. Within moments of his arrival, McCartney dashes over to his kit, grabs a pair of sticks and crashes through a few bars of a fast beat, heavy on the high-hat. It sounds distinctly Beatle-ish, or at least Wings-y.

McCartney points up at the corner staircase, which leads to the windowed control room where George Martin and the engineers worked. “That was where the grownups lived,” he says. “Those stairs were so iconic, it’s engraved in your memory like a dream.”

It’s a windy late-January day, but in keeping with his eternal boyishness, the 69-year-old isn’t wearing a jacket – just a black North Face vest over a pressed denim button-front shirt that’s neatly tucked into his dark jeans, possibly also ironed. On his feet are black running shoes with white trim: If a Hard Day’s Night mob scene should break out, he’s ready to move. His ever-fab hair is more tousled than usual, and he looks a little pale today – he’s been working too hard.

“This has so many memories for me, you couldn’t imagine,” McCartney says. “It’s unbelievable.” He points to the back corner. “John standing over there, doing ‘Girl.'” He sings the hook, imitating Lennon’s sharp intake of breath and miming a deep puff on a joint. “People thought it was that – it wasn’t! We just liked the sibilance of the sound. All the legendary stories that got created aren’t true. I just saw some Beatles program the other night, and in the first five minutes were four mistakes. This is why we don’t know who Shakespeare was or what really happened at the Battle of Hastings.”

As the crosswalk incident suggests, a mythic four-headed shadow sometimes threatens to obscure Paul McCartney, actual living human – newlywed, near-billionaire, strict vegetarian, father of an eight-year-old girl (and four adult children), ageless performer of three-hour rock shows, frenetically active songwriter and recording artist, composer of ballets and symphonies, knight of the realm. With his new album, Kisses on the Bottom, McCartney is adding “crooner of standards” to that list – it’s a jazzy collection of pre-rock tunes, with a couple of McCartney originals in that style snuck in.

He had delayed the standards album for years, in part because other people -from Ringo Starr in 1970 to Harry Nilsson in 1973 to Rod Stewart for what feels like the past thousand years – kept doing it. He also was hesitant to reinforce the once-prevalent image of him as a mere sentimental balladeer, the supposed flip side to John Lennon’s raw rocker. “I am over it,” McCartney says. “If people don’t know the other side of me now, it’s too late.” Still, Kisses is a one-off. A week before the album’s release, McCartney is already working on a new rock record. So far, he’s been playing all the instruments himself: The bass, guitars, keyboards and drum kit set up in Studio Two are all his. “The plan was to do what I’m doing now, which is to almost immediately start into another studio album, so people don’t think that that’s it, I’m now in the jazz genre.”

Today he’s recording a song for that next album called “Hosannah” – an acoustic ballad that wouldn’t be out of place on his first solo LP, 1970’s McCartney (another one where he played everything). As he puts headphones on and gets down to work – summoning that trumpetlike tone from his familiar old violin-shaped Hofner bass, pounding his foot to the beat – it’s almost hard to hear him with all the ghosts hanging in the air.

But McCartney doesn’t see it that way: He likes working here, and he wears the past as lightly as he can. “As far as things hanging over it, that’s something you live with,” he says. “I live with that. When I write a song, I have my other songs hanging over it. I suppose the minute you write a decent song, that’s a curse. You’re always like, ‘Oh, shit, I’ve just written “Eleanor Rigby,” how am I going to top that?’ I think you go, ‘I’m not.’ You just realize you’re not going to top it, but you write ‘Blackbird.’ You go in another direction or whatever. If you’re lucky. I’ve always been aware of that phenomenon, but I’ve never let it block me.”

McCartney is sufficiently self-aware to grasp another irony: Unlike other pop and rock artists who’ve recorded standards albums, he was responsible for knocking the Great American Songbook off its shelf in the first place (with help, of course, from Lennon and Bob Dylan). “We noticed it happening,” he says. “We would see people we had admired saying, ‘Oh, the Beatles have ruined it for us,’ and we didn’t mean to do that. We were just getting on with our own thing.

“We didn’t want to lay waste to the past, but it happened that way, so that people like Harold Arlen, who we greatly admired for writing things like ‘Somewhere Over the Rainbow,’ fell out of fashion as we came into fashion, and there was no longer such a desperate call for great writers like Leiber and Stoller, because people were starting to copy us and write their own stuff. So the Hollies and the Stones would then start writing, thinking, ‘This is kind of a cool idea.’ So, yeah, it did start a fashion, which tended to wipe out, regrettably, some of our favorite people.”

Its the day after his recording session, and McCartney is back in Studio Two, sitting on a folding chair at a small wooden table, right between the vintage keyboards he’s brought in. He’s eating a bagel topped with a mix of hummus and the salty British condiment Marmite, periodically exercising what must be a knightly privilege to talk with his mouth completely full. He insists I try some of the hummus – “It’s the best in the world, very creamy” – scraping a bit onto a corner of his plate: “Dip your finger in that and try it, come on!” I comply, noticing my finger shaking slightly on its way: Beatle hummus!

McCartney has been thinking lately about pre-rock standards’ heavy influence on the Beatles’ song writing – he and Lennon were already in their teens before they first heard Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly. “We grew up watching Fred Astaire films, and then it was kind of swept aside by rock & roll,” he says, biting his bagel, “but we still have that influence. The Rolling Stones were influenced by the blues, and we were influenced by rock & roll – blues, to some extent – but also, without knowing it, the melodic element of the Beatles, and some of the structural elements, came from the backs of our brains, which was this old stuff that our parents had sung.”

McCartney’s father, Jim, was a jazz trumpeter who had a band in the Twenties. He was also an amateur pianist, and some of Paul’s earliest musical memories are of lying on the floor by his piano, listening to his father play the kind of songs Paul sings on his new album. “There’s no recordings of my dad,” he says. “But my soul’s camera has got it. I think he was very good, but he wouldn’t have thought he was good enough to be a professional. The people who hired his band obviously didn’t think they were very good, because he had to keep changing its name to get another gig.” Later, his dad would lobby to have the Beatles cover Gershwin’s “I’ll Buy a Stairway to Paradise” – instead, they did songs like “Your Mother Should Know” and “When I’m Sixty-Four.” “Granny music,” Lennon would call it – though McCartney is quick to note that John liked the old songs too.

McCartney recorded Kisses on the Bottom with a veteran standards-and-jazz producer, Tommy LiPuma, who brought in pianist Diana Krall as musical director. McCartney already knew and liked her: He had attended her wedding to his old collaborator Elvis Costello “at Elton’s house.” They mostly worked in L.A.’s Capitol Studios – where McCartney sang through a microphone used by Frank Sinatra and Nat “King” Cole – and in New York, where McCartney insisted on going to the studio on the day Hurricane Irene was supposed to hit. “W’hat’s missing in a lot of people who interpret this music,” says Krall, “is that they just think, ‘Hey, we’re just singin’ standards, babe,’ and it’s not that. It’s heavier than that. Paul finds his own story in it.”

One of the McCartney originals, “My Valentine,” was written for Nancy Shevell, the glamorous 51-year-old American businesswoman he married last October. The first line – “What if it rained/We didn’t care” – comes from something she said on a Moroccan vacation. McCartney ran over to an old piano in their hotel, where the song came out almost all at once. After two very public marriages, McCartney is reluctant to talk about the third – but he admits it’s brightened his outlook.

“It has, yeah,” he says, with a slow nod. “I believe in love. The Beatles sang about it; I’ve sung about it; everyone else sings about it. Probably you and your wife believe in it. It’s a pretty popular idea, this thing! So now to find love after a divorce is great, it’s very refreshing. And Nancy’s great, she’s intriguing, interesting, lovely, smart, emotional and all the things you would want in a mate. She’s absolutely beautiful. She’s funny, she’s canny, she’s great, it’s all there.” Shevell’s reaction to McCartney’s latest silly love song was understated. “She’s a little shy, so she just dimples shyly,” he says. “But I know she likes it. She didn’t go crazy – ‘Listen to this, it’s a song he just wrote for me!’ – but I know she appreciates it.”

Up in Studio Two’s control room, the most melodic songwriter of his generation is making some seriously horrifying noise. McCartney is twisting knobs on an ancient tape machine, messing with a loop of a guitar lick he just played. He speeds it up until it becomes a beyond-Yoko shriek, slows it down until it sounds like droning sludge. He punches “stop” and smiles. “We do have I fun, don’t we?”

He’s working with producer Ethan Johns – the tall, bearded son of producer-engineer Glyn Johns, who worked on Let It Be – on potential tape-loop overdubs for “Hosannah.” In the corner is a Pro Tools setup, though Johns is also recording on analog tape. “Is that enough?” McCartney says after a few more licks. “I could go all day!”

He puts down his ’57 Les Paul (“There was a time when I had just one,” he says when Johns admires it. “Changed me own strings!”) and picks up a microphone. He loops some reverb-y “whoos” that sound like a ghostly Little Richard, then brings Johns over to harmonize on some “aaahs” and “mmms.” Sped up or slowed down, they sound like a trippy nightmare. McCartney laughs as he heads down the staircase, ready to overdub some bass.

“All that, and no drugs involved!”

McCartney says he’s quit pot altogether, after many years and many inconvenient busts – most notably in Japan, when he famously ended up in jail for nine days.

“I did a lot, and it was enough,” he says. “I smoked my share. When you’re bringing up a youngster, your sense of responsibility does kick in, if you’re lucky, at some point. Enough’s enough – you just don’t seem to think it’s necessary.”

Did he expect it to be legal by now? “Well, I certainly requested it a bunch of times,” he says. “I don’t know, it’s such a difficult argument. I feel like I’ve done my bit, and yeah, I am a bit surprised that it’s not legalized. You know the argument that if booze is legal, why not that, and then the argument against it is that we don’t need another [legal drug], but the argument against that is that you’ve got it, so don’t pretend you haven’t. I’m not going to be the judge of how to deal with it, somebody else can figure that out.”

McCartney’s “lavatory reading” these days is Keith Richards’ Life. He hasn’t gotten to the part about himself yet – and the book hasn’t succeeded in persuading him to write a memoir of his own (though he did participate extensively in Barry Miles’ authorized 1997 biography): “I’ve got really too much going on to sit around and write stuff about my past. So all of that ends up with me going, ‘I can’t be bothered.'” He confirms that he and Richards struck up a belated friendship a couple of years back, and batted around ideas for collaborations that will most likely never come to be. “We had some really funny ideas, and I kept saying, ‘You know, Keith, this is a dangerously good idea, this is ridiculous, bordering on the brilliant.'”

McCartney doesn’t share Richards’ self-image as a rock & roll outlaw. Unlike Lennon, McCartney never mailed back his Member of the British Empire medal in protest of anything, and he happily accepted a knighthood in 1997 – Richards was incensed when Mick Jagger received the same honor. “As a guy in a rock & roll band, you do ask yourself, ‘Is this cool to do?'” McCartney says. “But I saw all sorts of working-class guys who were proud to be honored by the queen. That was more impressive than the supercool dudes who said, ‘No way, man.’ I see their argument, but it seemed to me that it’s a pretty cool prize to be given by a pretty cool lady.”

He’s still convinced that Her Majesty is a pretty nice girl – and will perform at her Diamond Jubilee concert, marking 60 years on the throne, in June. “You have to see it from the perspective of | kids who grew up with her coming to the throne,” he says. “I remember being on a bus in Liverpool and hearing some kid yelling, ‘The king is dead!’ like in a movie. Suddenly it was this Princess Elizabeth, who we always saw as a bit of a babe. We were the right age, and we were quite impressed by her bust! Then when we met her, it was like, ‘She’s OK, she’s cool.’

“I’ve always admired the way she’s handled this massive job she’s got. I see the argument of anti-monarchists, because it’s an amazingly old-fashioned affair, but I say to people, ‘Who are we going to have lead our country in the big celebrations, opening the Olympics: David Cameron? Tony Blair?’ I’m not sure about that.” McCartney can be something of a small-c conservative: Chatting about the state of the world in Studio Two, he delivers a disquisition about government debt that’s hard to imagine coming from any other rock god: “There’s this whole idea of ‘borrow forever,’ whereas my theory, which was instilled in me by my dad, was, ‘Don’t get under an obligation to anyone, ever. If you need anything, wait until you can afford it, then get it.'”

He’s no right-winger, however: McCartney is baffled and angered by climate-change deniers, and vastly prefers Barack Obama to George W. Bush. He infuriated Fox News pundits when he visited the White House in 2010: After playing “Michelle” for the First Lady, he said, “It’s great to have a president who knows what a library is.” He even removed his turgid post-9/11 anthem “Freedom” from his set lists in the wake of the Iraq War. “When I said, ‘I will fight for the right,’ I meant, ‘We shall overcome.’ But unfortunately, immediately after that, I realized it would get construed as more militaristic. So we don’t play it.”

Twenty years ago, when McCartney turned 50, he remembers his then-manager pushing the idea of retirement. “It’s only right,” he was told. “You really don’t want to go beyond 50, it’s going to get embarrassing.” In June, McCartney will be 70 (“I’m never going to believe I’m 70, I don’t care what you say,” he says. “There’s a little cell in my brain that’s never going to believe that”), and he still has no plans to stop touring or recording. “You get the argument ‘Make way for the young kids,'” he says. “And you think, ‘Fuck that, let them make way for themselves. If they’re better than me, they’ll beat me.’ Foo Fighters don’t have a problem, they’re good. They’ll do their thing.

“If you’re enjoying it, why do something else? And what would you do? Well, a good answer is ‘Take more holidays,’ which is definitely on the cards, but I don’t seem to do that. I love what I do so much that I don’t really want to stop. I’m just kind of casually keeping an eye on how I feel, and onstage, it feels like it’s always felt. So for the time being, the band’s hot, I’m really enjoying myself, still singing like I sang, not experiencing, touch wood, any sort of problems to speak of. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

It doesn’t hurt that his touring schedule has been reduced to shorter, intense bursts in recent years, largely because of his shared-custody arrangement for his eight-year-old, Beatrice. “We don’t do the big sloggo Lour, we don’t do the big U2-Stones go-out-forever thing, and get a bit fed up with it,” says McCartney, who’s planning some dates for later this year. “What we do now is events and selective dates. Because of my custody situation, I can only do that. At first, we thought, ‘Oh, God, is this going to be a problem?’ and it’s actually turned out to be some kind of a blessing.”

He can see himself rocking well into his eighties. “I can imagine it,” he says, “As to whether my imagination will come true, I don’t know. The last couple of years, I’ve gotten into guitar – so there’s all sorts of little things that crop up that entice you forward, and you go, ‘Hmm, I’d like that.'”

I broach the idea of actually dying onstage – would he be into it? He recoils slightly, then smiles. “What kind of question is that? I must say, that’s not in my imagination. Rocking on until a grand old age…the only thing would be when it’s not pleasant anymore, then it would be ‘That’s a good time to stop.’ But it’s way too pleasant at the moment. And it pays. Good gig, man. But I know exactly where you’re coming from, though. How long can this go on…?”

In the corner of the attic study of McCartney’s private studio in the English countryside, he’s playing rockabilly riffs on a bulky old stand-up bass with white trim on its edges. The instrument traveled a long way to get here: It belonged to Bill Black, Elvis Presley’s original bass player. “This is it, man – come and touch it,” McCartney says. “I have an image of this and my little Hofner bass, big and little. The amount of music that we like that’s been played on those two instruments…”

The bass was a gift from his late wife, Linda; on the other side of the room, the early-afternoon light shines through a stained-glass image of B.B. King in mid-solo ecstasy, adapted from a photo she took. Next to the bass is a tiny old wooden desk – taken from the Liverpool school McCartney and George Harrison attended at the same time Black was strapping that bass to the top of a 1951 Lincoln to tour the South with Presley and Scotty Moore.

By the staircase is a chunk of a recently torn-down London concert venue that the Beatles played – McCartney sent another piece to Starr for his birthday, “I wouldn’t be allowed to keep all of this in the house,” McCartney says. “Guys can be hoarders – we don’t want to chuck anything out. And mine is Beatle hoarding, so I really don’t want to throw anything out.”

Settling on a cheery yellow couch near a vase of fresh flowers, he mentions being struck by Harrison’s openness on the psychological havoc wreaked by Beatlemania – a frequent topic in Martin Scorsese’s Harrison film. “I think we all experienced the trauma that George vocalized,” McCartney says. “I liked to hear George talking about it, because he’s getting it out in the open. For me, it’s something that was more internalized, and my upbringing would lead me to say, ‘Yeah, OK, it’s a trauma, but get on with it.’ It’s like, ‘Yeah, what are you gonna do, sit around and moan? You were just in the most famous band in the world. You wanted to be, it pays good money, you’ve had a lot of great times, and some shitty times, so what are you going to do, concentrate on the shitty times or just deal with it?'”

McCartney has seen a therapist, but not for that stuff. “I’ve done therapy, yeah, in divorces and things, and losing your wife. It’s not to do with the Beatles, believe me.”

While all four Beatles were still alive, the idea of getting back to where they once belonged was never off the table. ‘’There was talk of re-forming the Beatles a couple of times,” McCartney says casually, ‘”but it didn’t jell, there was not enough passion behind the idea. There was more passion behind retiring the Beatles than there was about re-forming. We’d all said, very convincingly, ‘We’ve come full circle’.

“And more importantly, it could have been so wrong that it spoiled the whole idea of the Beatles, so wrong that they’d be like, ‘Oh, my God, they weren’t any good.’ So the re-formation suggestions were never convincing enough. They were kind of nice when they happened – ‘That would be good, yeah’ – but then one of us would always not fancy it. And that was enough, because we were the ultimate democracy. If one of us didn’t like a tune, we didn’t play it. We had some very close shaves. ‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’ was a pretty close shave.”

Lennon and McCartney did once get together in a recording studio well after the Beatles’ breakup: In McCartney stopped in while Lennon was working on Pussy Cats with Harry Nilsson in Los Angeles. Eventually, they tried to play some music along with Nilsson, Stevie Wonder and others. As immortalized on the infamous bootleg A Toot and a Snore in ’74 (which McCartney has never heard), the results were horrendous. “I’d imagine it’s not very good,” says McCartney. He finds the story more comic than tragic: “We were stoned. I don’t think there was anyone in that room who wasn’t stoned. For some ungodly reason, I decided I’d get on the drums. It was just a party, you know. To use the word ‘disorganized’ is completely understating it. I might have made a feeble attempt to restore order – ‘Guys, you know, let’s think of a song, that would be a good idea’ – but I can’t remember if I did or not.”

This morning, downstairs in his studio, Paul McCartney sat down and wrote a new song. It’s what he does. Whether he’s newly divorced or newly married, happy or sad, the music arrives, “I had some thoughts last night, I woke up this morning, and took my daughter to school. I was thinking in the car, coming back. I put the words together, and I just did the melody while you were waiting in the kitchen.” He’s working with Mark Ronson today – one of several producers he’s considering for the record – so he decided to write something appropriate. “Mark DJ’d at our wedding reception, so I’m thinking ‘party’ – I came up with a song, ‘The Life of a Party Girl.’

If anything, songs come too easily to McCartney, which may explain how the Beatles-level songs in his solo catalog can coexist with throwaways like “Let ‘Em In.” “I have to be careful that something just doesn’t come out too bland,” he says. “Paul Simon works his music much more than I do, with a first draft, a second draft, third draft. I do that as well, but not as much as he does. It’s different kinds of music. I’m not sure that Arthur ‘Big Boy’ Crudup thought too much about ‘That’s All Right, Mama.’ [Allen] Ginsberg used to say, ‘First thought, best thought,’ and then he’d spend hours editing his work. I do sometimes write one and look at it and shudder and say, ‘l don’t like that.'”

At the deepest level, McCartney has little idea where all the melodies come from. He still hasn’t figured out how he wrote “Yesterday” in his sleep. “I don’t like to use the word ‘magic’ unless you spell it with a ‘k’ on the end, because it sounds a bit corny. But when your biggest song – which 3,000 people and counting have recorded – was something that you dreamt, it’s very hard to resist the thought that there’s something otherworldly there.”

Does he feel like God sent him a giant check? “Or, I unwittingly sent it to myself,” he says. “I have this sort of theory that all the time you’re inputting your computer with information from the world, and one day it prints out for you. I think in the case of ‘Yesterday,’ it was an involuntary printout. On the other hand, it might be God, I’m not ruling that out.”

McCartney always seemed to be the least spiritually inclined Beatle (or the second-least – who knows what was going on with Ringo). There’s no “My Sweet Lord” in his repertoire – not even an “Across the Universe.” “I believe in a spirit, that’s the best I can put it,” he says. “I think there is something greater than us, and I love it, and I’m grateful to it, but just like everyone else on the planet, I can’t pin it down. I’m happy not pinning it down. I pick bits out of all the religions – so I like many things that Buddhists say, I like a lot of things that Jesus said, that Mohammed said.”

And in the end, McCartney is convinced it all boils down to a very brief message, which he reveals with great Liverpudlian gravity: “Be cool and you’ll be all right,” he says. “That’s rock & roll religion.”

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.