Wednesday, February 20, 1980

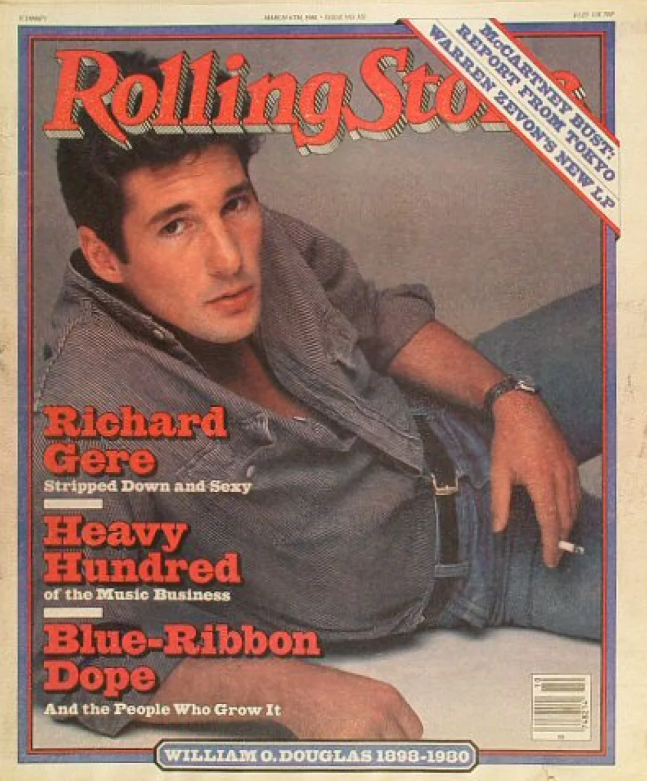

Interview for RollingStone

Paul McCartney: Ten Days in the Life

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Wednesday, February 20, 1980

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Previous interview Jan 12, 1980 • Linda Eastman / McCartney interview for New Musical Express (NME)

Article February - April 1980 • Paul McCartney writes his "Japanese Jailbird" memories

Session Late February 1980 • "McCartney II" double-album editing

Interview Feb 20, 1980 • Paul McCartney interview for RollingStone

Article Feb 26, 1980 • Paul receives the Reader's Award For Outstanding Music Personality of 1979

Article Feb 27, 1980 • Rockestra wins a Grammy Award

Next interview Jun 14, 1980 • Paul McCartney interview for Melody Maker

Unreleased song

Officially appears on Help! (Mono)

This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

“This sceptered isle has never looked so good. I have never appreciated so much being able to walk in the woods and breathe English air.“

The speaker was neither Wordsworth nor Keats, but Paul McCartney. Prisoner “22” was happy to be home on his eight-acre farm in Sussex after spending almost ten days in a Japanese detention cell. The ex-Beatle had been arrested on January 16th by customs officers at Tokyo International airport for carrying almost 220 grams of marijuana – worth about $2000 on the Tokyo streets.

McCartney, now the world’s most famous pot smoker, was deported by Japan and flown to England via Anchorage and Amsterdam. He had hoped to spend a day or two resting in Holland [!], but Dutch authorities considered McCartney a deportee in transit and would not let him leave the airport transfer area (although they welcomed him to return after first touching English soil). He then flew by private jet to Lydd Airport in the County of Kent, just across the English Channel and near the family farm.

Though McCartney was, in fact, a deportee, his legal team seemed glad deportation was the worst of his troubles. “We were so lucky,” McCartney’s lawyer in Japan, Tasuku Matsuo, kept repeating after Paul left that country.

Japanese law is not known for its lenient treatment of drug offenders. And although McCartney spent time in jail and Wings was forced to cancel its long-awaited tour of Japan, in the end the Tokyo district prosecutor released him and rid him of all criminal charges. Since he was deported without charge or conviction, he should be able to enter the U.S. without difficulty.

The prosecutor’s decision was reportedly based on McCartney’s inadequate information on the legal status of marijuana in Japan and the prosecutor’s judgement that the detention and concert cancellation were ample punishment. Some speculated that an indictment was simply more trouble than a deportation. Matsuo said an important factor was McCartney’s claim that the marijuana found in his suitcase was for his personal use.

But according to John Eastman, McCartney’s lawyer and brother-in-law, Paul was deported because his visa was lifted when he was arrested and he was technically an illegal alien. Eastman had flown to Japan from New York to help sort out the complex legal problems facing McCartney and Wings.

After the arrest, the district prosecutor had ordered McCartney detained at the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department while he decided what legal course to take. About fifty fans, mostly high school girls, kept vigil outside the station, singing Beatles and Wings songs and calling “Poru, Poru.”

“At first I thought it was barbaric,” said McCartney, back in England, about his time in jail. “I was woken up at six in the morning, then had to sit cross-legged for a roll-call. It was like ‘Bridge on the River Kwai’. They shouted out “22” in Japanese, and I had to shout back, “Hai.“

“I became matey with a chap next door,” McCartney told the London Daily Mirror. “He could speak a bit of English. Funnily enough, he was inside for smuggling pot.“

McCartney sang with the five prisoners with whom he shared a communal bath, working up renditions of “When the Red, Red Robin,” “Take this Hammer,” and, upon his mates’ special request, “Yesterday.”

But he spent most of his time alone in a four-man cell or answering questions about his case from officials of the Japanese Ministry of Finance, Health, and Justice. At night, he slept on a Japanese-stye mattress. Although officials denied his request for a guitar, or pen and paper to use for writing songs, they did allow McCartney to follow his vegetarian diet. He was even able to buy extra fruit and vegetables from the police.

According to Matsuo, Linda McCartney was visited her husband twice, and the couple amused the guards by pretending to kiss and touch hands through the glass that separated them. While detained, McCartney made a

paper-clip wedding ring, since his real one was confiscated. “It’s the sort of gesture Linda and I will look back on rather romantically,” he said. The ten-day separation was the longest McCartney and his wife had been apart since their marriage almost eleven years ago. “It was terribly hard for Linda and it was terribly hard for me.”

In Japan, Linda took the couple’s four children around Tokyo and shopped for food to make vegetarian sandwiches, which she delivered to the police station daily. (McCartney responded by sending bouquets of flowers to his wife via Matsuo.) Linda spoke to the press once with Matsuo, Eastman and British promoter Harvey Goldsmith, appearing relaxed and vowing not to leave Paul alone in Japan, even if it meant waiting for years.

Also falling victim to the bust, of course, was Wings’ tour of Japan. The band had been scheduled to play eleven concerts, and around 90,000 were sold within a few days. For Udo Artists, the Japanese tour promoters, the affair turned into what one spokesman described as a “nightmare.” Udo claimed losses of about $2.5 million from the tour’s

cancellation.

“Paul paid Udo every penny they were owed,” said Eastman, once back in New York; he would not reveal just how much that was. “Everyone involved with the tour was fully compensated. No one lost any money, except, of course, Paul. And nobody had to wait for their money. It was all taken care of before Paul left Japan.” (McCartney told Eastman

he would still like to tour Japan if officials allow him to return.)

As for whether the affair gave McCartney second thoughts about marijuana, he said, “Yeah, and third. The whole thing was too severe. Marijuana is not as dangerous as some people make it. A lot of people, especially younger people, know that. In America, even president Carter, when asked, said he favored decriminalization. We’re all on drugs, cigarettes, whisky. I was in jail for ten days, but I didn’t go crazy because I wasn’t able to have marijuana. I can take it or leave it.“

But McCartney told the London Sun, “I was really scared thinking I might be in prison for so long…and now I have made up my mind never to touch the stuff again. From now on, all I’m going to smoke is straightforward fags. No more pot.”

Some people thought McCartney had provided a bad example for his young fans. Bertram Parker, head of Paul’s old school, the Liverpool Institute for Boys, was quoted saying so in the English press. Asked about the criticism, McCartney said, “They’ve been saying that about me for years. I have always been accused of setting bad examples. I think a lot of people set worse examples, like governments. They set an incredibly bad example.“

McCartney’s ordeal was an immediate sideshow in Britain. The day after his arrest, he was frontpage news on every tabloid, taking up the entire lead page of the Daily Mail. PAUL IN CHAINS, the headline screamed, above a picture of the handcuffed musician. Television reports from Japan were broadcast nightly.

In Japan, the national press reacted to the case with varying degrees of ridicule. McCartney was generally portrayed as either too ignorant to know the severity of Japanese drug laws or too arrogant to care about them. But if the Japanese dailies showed little sympathy, the weekly gossip magazines seemed downright anti-Paul. “Our Hero

Betrayed Us,” read one headline.

Eastman, however, had nothing but kind words for the Japanese. “They’re very decent and civilized people. They wanted everyone to save face.“

Despite the mass interest in both countries, however, there was little public action in either. The Wings fan club in Japan collected a thousand signatures demanding McCartney’s release. A few pro-Paul fans turned up at the deserted Budokan on the night of the scheduled concert and annonced to reporters they were refusing a refund and keeping their tickets as a symbolic gesture. Although English fans were less demonstrative, McCartney’s release sent a wave of relief through the country. The London Sunday Times ran a front-page cartoon of a smiling politician saying, “Thank goodness something went right this week.”

The last word, though, must be McCartney’s. “All I want to do now is get home,” he reportedly said on the plane from Japan, “and hear the grass grow.“

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.