Sunday, October 14, 2007

Interview for The Observer

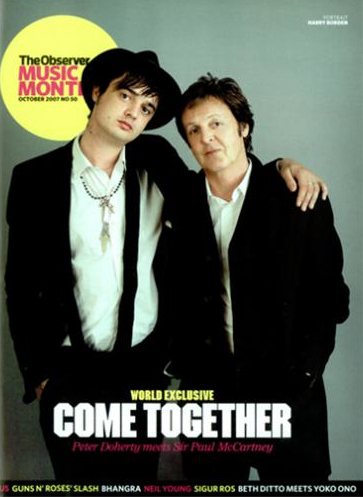

Pete Doherty meets Paul McCartney

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Last updated on October 16, 2020

Sunday, October 14, 2007

Press interview • Interview of Paul McCartney

Last updated on October 16, 2020

Previous interview 2007 • Paul McCartney interview for Billboard

Article October 2007 • Paul McCartney gets Q's Icon Award

Article Oct 10, 2007 • Paul McCartney supports the charity "They Eye Fund"

Interview Oct 14, 2007 • Paul McCartney interview for The Observer

Concert Oct 22, 2007 • Live At The Olympia

Concert Oct 25, 2007 • Electric Proms

Next interview Nov 12, 2007 • Paul McCartney interview for paulmccartney.com

Officially appears on Hey Jude / Revolution

Officially appears on The Beatles (Mono)

Officially appears on Rubber Soul (UK Mono)

Officially appears on Mull Of Kintyre / Girls’ School

Officially appears on Strawberry Fields Forever / Penny Lane

Officially appears on Help! (Mono)

Paul McCartney: What do The Beatles Mean ?

Nov 26, 1967 • From The Observer

1969 • From The Observer

Mar 11, 2001 • From The Observer

2003 • From The Observer

When the McCartneys came for lunch

Apr 29, 2007 • From The Observer

The interview below has been reproduced from this page. This interview remains the property of the respective copyright owner, and no implication of ownership by us is intended or should be inferred. Any copyright owner who wants something removed should contact us and we will do so immediately.

Read interview on The Observer

From paulmccartney.com, October 9, 2007:

The Observer Music Monthly this Sunday, 14 October, features exclusive interviews with icons of the sixties by contemporary musicians. Babyshambles singer Pete Doherty is allowed out of rehab for the afternoon to interview Beatles legend Sir Paul McCartney, William Orbit talks to Sir Michael Caine about his recent chill-out album Cained and Beth Ditto interviews her all-time heroine, Yoko Ono.

Pete Doherty talks to Sir Paul McCartney about the punk movement. “I remember being in traffic, in London, and when you’re famous you try really hard not to get noticed so much, especially if you’re in a traffic jam, and suddenly there was a bunch of punk kids, and I’m like, ‘Oh no how’s this going to work out? What’s the attitude going to be?’ and you’re vaguely apprehensive, and they were great, they came up: ‘Paul! Love that Mull of Kintyre , Paul!’ So you realized it wasn’t as one-sided as you thought everything was. It was a shake-up.”

The idea has been put to Sir Paul McCartney and out of everyone he could have picked to interview him, he’s chosen the Babyshambles singer and tabloid fixture Peter Doherty. Only trouble is, Pete is currently in rehab, but after some tactful negotiations, he is allowed out of his clinic for the afternoon. So it is, with only OMM otherwise present in the hotel suite, that the two sit down to talk one recent Thursday afternoon. But first, Pete wants to give Sir Paul a present …

Sir Paul: Wow! I’m terrible like that. People are really sort of nice at bringing me things. So someone said: ‘Would you like to do an interview? And who would you like to do, and I said: ‘Pete’. ‘Cause otherwise it’s just some real boring person who you’re not interested in.

We’ve met briefly once before, backstage at a Little Britain show, and I’d seen you on the Jonathan Ross Show, which I thought was very cool. To me, there was all the newspaper stuff saying, ‘He’s out, he’s out of it,’ so I was like, ‘He’s going to miss a few notes here,’ but you were spot-on; really nailed the piece you were playing.

Pete: Yeah, I remember asking you on the stairs at Little Britain about [the Beatles song] ‘I Will’. I just love that. A minor, D minor.

Sir Paul: That’s great. I do a lot of Beatles stuff now, and revisiting it is really interesting – just looking at what chords you were using and revisiting the lyrics, you know, ’cause some of them back then you thought, ‘Well you’re just writing a song of straight love lyrics maybe.’ But playing them now, some of them have a different significance for me, you know, they just seem a bit deeper. I was just some young guy and, you know, pretty hot, pretty on the ball. It’s nice to do the songs for that reason. ‘That was good, did I say that? Yes, you did.’

Pete: I wanted to ask about some of your old clobber …

Sir Paul: My what?

Pete: Your clothes …

Sir Paul: Well, we started off in Hamburg. Before that it was, like, teddy boys, you know. Then Hamburg, it was leathers. That was after Gene Vincent really, we were just mini Gene Vincents. That was one of the great things about Hamburg, you would get these guys coming through – Little Richard, Gene – and you’d be hanging with them, instead of just buying their records. That was cool. Gene was a nutter. A beautiful nutter.

Pete: I heard you wrote ‘Michelle’ to pull girls …

Sir Paul: Yeah, we used to go to these art school parties because John was at art school and me and George were at the school next door, which is now a performing arts school. John was that little bit older than us, which at that age is impressive. He was a year-and-a-half older than me and you really look up to people like that. But it’s funny because I don’t think I had that same feeling with Ringo, who I think was a few months older than John.

John was a pretty impressive cat – being a year-and-a-half older and going to art school, all that was a pretty cool combination for us. So we’d tag along to these parties, and it was at the time of people like Juliette Greco, the French bohemian thing. They’d all wear black turtleneck sweaters, it’s kind of where we got all that from, and we fancied Juliette like mad. Have you ever seen her? Dark hair, real chanteuse, really happening. So I used to pretend to be French, and I had this song that turned out later to be ‘Michelle’. It was just an instrumental, but years later John said: ‘You remember that thing you wrote about the French?’ I said: ‘Yeah.’ He said: ‘That wasn’t a bad song, that. You should do that, y’know.’

Pete: When I first met Carl [Barat, co-founder of the Libertines], I was 17 and he was about a year-and-a-half older than me. We had this song called ‘France’, a jazzy little number. I couldn’t really play guitar then, not properly. I was convinced I was going to be the singer and he was going to be the guitarist, like Morrissey and Marr, but a few years in, he was convinced that he was going to sing as well so I had to learn the guitar.

Sir Paul: Like me being a bass player. Which now I’m very proud of, it’s my role and I’m happy with it. But at first it was the loser role in the group. It’s usually the fat guy who stands at the back. So I was a bit unhappy when I got that job, I wanted to be up front with the guitar. But I had such a crappy little guitar, a Rosetti Lucky 7, and it was cheap. My Dad was very against the never-never hire purchase, and was like, ‘Pay your way, lad. Never be under an obligation to anyone.’ Which was good advice. But the others – John’s Auntie Mimi and George’s Dad – didn’t have that problem – so they would get their guitars. I had this crappy thing which was really just a piece of wood with a pick-up on it. It looked quite glamorous, but we took it over to Hamburg and I think someone smashed it – like early Pete Townshend. Fuck!

Pete: I had this guitar which was £20. It was a big old thing, and I think it came from India. The make was the same font as Gibson, so I doctored it with a little bit of marker pen.

OMM: How did you both handle, at different points, the adjustment from writing with a partner to writing on your own?

Sir Paul: The good thing for me was that we hadn’t always written as a partnership. I mean, we were a partnership on the road, when we had twin beds. But then when we actually got houses, I would write something on a day when I wouldn’t see him. I had kind of done ‘Penny Lane’ and ‘Yesterday’, when he’d done ‘Strawberry Fields’ at his place. We’d get together and polish them, but we had established this thing of writing separately. It took the edge off it when we had to completely write separately I still miss not having someone to check things with, though.

Pete: Well, I’m probably more in a writer partnership now than at the Libertines stage. Writing with Mick Whitnall on the latest Babyshambles album was pretty much 50-50, or 40-60 maybe. We were bouncing off each other.

Carl was always quite tight with quality control, like I had this line in my head for years that I always wanted to put it in a song, and he used to go cold when I said it. I can’t remember the name of the poet now, but he became resident poet of Barnsley football club [it was Ian McMillan, poet, playwright and regular Newsnight Review contributor] … [Pete sings] ‘It’s a charmed life, double as a poet for your favourite team’ and every song we would write I would try and get that in.

Sir Paul: …and always get blown out. Have you got it in anything yet?

Pete: No. Maybe next time.

Sir Paul: Our first little cool bit of collaboration came when … I’d met John and he said: ‘What do you do?’ And I said: ‘I play guitar and I really like rock’n’roll and Eddie Cochran.’ And he said: ‘Ah, well, I’ve written a couple of songs.’ And I said: ‘So have I.’ They weren’t really anything, but we had independently tried to write. So we used to go to my house, when my dad was at work. I can see us in the front living room and in the parlour – this little house that is now national bloody heritage [Sir Paul’s boyhood home was acquired by the National Trust in 1998] – just standing there, singing. I mean those early days were really cool, just sussing each other out, and realising that we were good. You just realise from what he was feeding back. Often it was your song or his song, it didn’t always just start from nothing. Someone would always have a little germ of an idea. So I’d start off with [singing] ‘She was just 17, she’d never been a beauty queen’ and he’d be like, ‘Oh no, that’s useless’ and ‘You’re right, that’s bad, we’ve got to change that.’ Then changing it into a really cool line: ‘You know what I mean.’ ‘Yeah, that works.’ We’d have individual bits of paper. I have fond flashbacks of John writing – he’d scribble it down real quick, desperate to get back to the guitar. But I knew at that moment that this was going to be a good collaboration. Like when I did ‘Hey Jude’. I was going through it for him and Yoko when I was living in London. I had a music room at the top of the house and I was playing ‘Hey Jude’ when I got to the line ‘the movement you need is on your shoulder’ and I turned round to John and said: ‘I’ll fix that if you want.’ And he said: ‘You won’t, you know, that’s a fucking great line, that’s the best line in it.’ Now that’s the other side of a great collaborator – don’t touch it, man, that’s OK.

Pete: Did you see they were giving out these supplements of great interviews with the Guardian over the past couple of months – Fidel Castro and Mae West, people like that. And they had an interview with John Lennon [with Jann Wenner, editor of Rolling Stone, from December 1970]. I’d never seen it before but it struck me as quite interesting, him saying that your tours had been like Satyricon.

Sir Paul: Like what?

Pete: Like Fellini’s [1969 film] Satyricon.

Sir Paul: Not really. I mean, it’s a bit of an exaggeration. It was definitely quite decadent. The whole thing about getting into a band was to get girls, basically. Money and girls. Probably girls first. So when you are on the road, and there was time for a party, we had a bunch of those. There was an element of Satyricon, although that overstates the case a bit. But there were certainly some elements that you wouldn’t talk about in the newspapers. Privately, I could tell a tale or two [laughs]. The funny thing is when later the rumour came out that John was gay, I said: ‘I don’t think so.’ I mean, I don’t know what he did when he went to New York, but certainly not in any of my experiences. We used to sleep together, top and tail it, you know. I always used to say: ‘Come on, I would have spotted something here.’ But what I spotted was completely the opposite. It was just chicks, chicks, chicks.

OMM: It must have been very different to today, when everywhere you go someone has a camera phone, and you can’t even go out of the house without someone reporting what you are doing.

Sir Paul: Yeah, that’s a bit of a hassle, isn’t it? No there was none of that really, no cameras. There was no reportage or paparazzi.

Pete: Really? If you look on YouTube there’s something called the ‘Egg of Kerbibble’. I filmed my mate getting hold of a paparazzi through some railings and he’s got an egg cracked right on his head, and if you look closely you’ll see another couple of eggs come flying across and catch him. Small compensation, do you know what I mean?

This bloke in Rome once took his camera off and cracked me round the head with it, and I’m bleeding. He was a bit bigger than me, the Italian photographer, but I thought I can’t back down now, so I sort of squared up to him. Luckily my mate jumped round and bit him on the neck.

Sir Paul: [looking mildly taken aback] And all you’re trying to do is …

Pete: Get into your hotel.

Sir Paul: Just trying to, you know, write some songs, and sing, and all this stuff comes with it. In truth, thinking back, it really didn’t exist like that. It was much easier to get around. I used to go to gigs on the tube, all those Odeons that were out in Walthamstow or wherever. I’d just go and walk into the gig, even at the height of the Beatles thing. It was just cool. You knew you could control it. All these girls going ‘Heeyy Paul! We love you!’ ‘All right, we’ll walk slowly towards the gig and I’ll do the autographs, but any shouting and I’m not going in.’ I kind of liked it then, me and my harem.

Pete: How old were you when you first had kids?

Sir Paul: 28.

Pete: That must have settled you down?

Sir Paul: We were quite sort of hippie about it though, me and Linda. We had a laid-back attitude. There’s a picture that I could not imagine being involved in now, but it was a real summery day and we were coming through Dublin airport and I’m carrying my daughter, Mary – who’s now got two of her own kids – and she’s completely naked.

Pete: Where were you when punk kicked off?

Sir Paul: At first, it was a bit of a shock. Heather [McCartney, Paul’s stepdaughter and Linda’s daughter from her previous marriage] was a punk, so she sort of brought it home and me and Linda were like, ‘You’ve cut all your hair off, darling.’ She used to have this long blonde hair and then suddenly it was spikey; tartan, pins, plastic bags and everything. And it was like, ‘Whoa!’ But she took us through it, and educated us. Played us the Damned and the Clash and the Sex Pistols and stuff, and so you gradually got it. Realised it was time for a shake-up. It was good. Like a mirror they put on you: ‘Oh yeah, we’re pretty boring, and these kids aren’t.’ The other thing is that it looked quite aggressive but it was a lot of image, which it had been for us. We were pussycats in leather, it’s not like we were big hard guys, and it was the same for a lot of our friends. Heather had dyed her hair and I remember one of her boyfriends had an ‘A’ on his jacket [the ‘A’ indicated ‘anarchy’]. And I was like, ‘What’s that stand for?’, and he said: ‘I don’t know.’ It’s a look, you know, and it looks good [laughs]. I remember being in traffic, in London, and when you’re famous you try really hard not to get noticed so much, especially if you’re in a traffic jam, and suddenly there was a bunch of punk kids, and I’m like, ‘Oh no, how is this going to work out? What’s the attitude going to be?’ and you’re vaguely apprehensive, and they were great, they came up: ‘Paul!’ ‘Love that “Mull of Kintyre”, Paul!’ So you realised it wasn’t as one-sided as you thought everything was. It was a shake-up.

Pete: What about the Smiths?

Sir Paul: Yeah, I like them. Linda was into Morrissey; they wrote to each other a lot. Big fans. I played with Johnny [Marr] a bit. It was original.

Pete: Falling guitar lines where there’s no chords and you spend three weeks trying to work out what he’s really playing.

Sir Paul: You could tell it was Morrissey. It was like his paint palette … [Pete starts singing the Smiths song ‘Still Ill’.]

Sir Paul: [appreciatively] Have you ever covered that?

Pete: No.

Sir Paul: It’s obviously a song you love. It’s in your blood.

Pete: I got it as a seven-inch from a second-hand shop in Nuneaton. It was on the wall, and I thought I was being clever, ’cause I nicked it – but I’d only nicked the sleeve. So I had to go back and pay for the record. As soon as the guitar started, I didn’t even listen to the rest of it, I just wanted to play it again and again. I didn’t want it to end …

Sir Paul: The nice thing about having kids is that you get a lot of that through them. You get the next wave of musical education coming off them. Heather particularly – she’s a big music buff, she went to all the shows. But for me, someone like Ray Davies and the Kinks would be like that for my generation.

Pete: I’ve got this image of you coming to London to live for the first time, going up some wooden stairs, into a room with a typewriter on the top floor of a Victorian house. Is that right?

Sir Paul: Well, I used to live in Wimpole Street, in Jane Asher’s house, which has great, great memories. In the early days we used to come down to London and then drive back up to Liverpool, but then we were working in London too much to just go back, so Brian Epstein, our manager, arranged for us to rent a flat in Mayfair, on Green Street.

Pete: Did you ever bump into Tony Hancock?

Sir Paul: Once, at Twickenham Film Studios. We’d finished the day and he’d finished. So it was: ‘We’re big fans of yours, Tone. We think you’re great.’ You could never think of anything else to say.

Pete: Have you read Hancock’s biography, When the Wind Changed? It’s got a really awful photo on the front of him! He’s all bloated at the bottom of these stairs. I don’t know if it’s supposed to be symbolic or something. How about Wilfred Bramble [Steptoe actor who appeared in A Hard day’s Night]?

Sir Paul: Dear old Wilfred. Later you start to realise he’s an actor, but to us he’s like a magic person. Now I can see that he actually got up in the morning, shaved and did stuff, but then he was just this magic guy. Wilfred was a fantastic actor but he would forget his lines sometimes. To us he was a God, and it was sort of embarrassing for him, but in a way it was fascinating.

We’d be in a lot of shows, but we’d be the only rock’n’roll band in them. Dances, comedians … it was a nice world for me.

Pete: In the early days of the Libertines we used to put on Arcadian cabaret nights. There’d be some girl climbing out of an egg, we’d try and get a couple of mates to tell a few jokes, performance poets, and then we’d play in the middle of it all. More people were on stage than in the crowd.

I photographed McCartney [for] a shoot for the Observer Music Monthly. He was to be interviewed by Pete Doherty, the singer and musician best known as the frontman for the Libertines. Doherty had been allowed out of rehab to interview him, so it was a great opportunity to photograph the two of them together, even though they made an incongruous pair.

I had plenty of time to shoot a series of pictures of Doherty on his own, but when McCartney arrived, the photographs of them both were done very quickly. I set up a grey background and took some shots, both as a record of their meeting and as a prelude to the interview. It was a brief but convivial shoot. McCartney was very courteous and professional, as well as being very gracious, considering the number of times he has been photographed.

From The Cosmic Empire – HARRY BORDEN, AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHER, DECEMBER 2016

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.