Album This song officially appears on the Hey Jude / Revolution 7" Single.

Timeline This song was officially released in 1968

This song was recorded during the following studio sessions:

January 24 - February 7, 2022

“Hey Jude” gets an Ivor Novello award

May 22, 1969

Mick Jagger hears “Hey Jude” for the first time

Aug 08, 1968

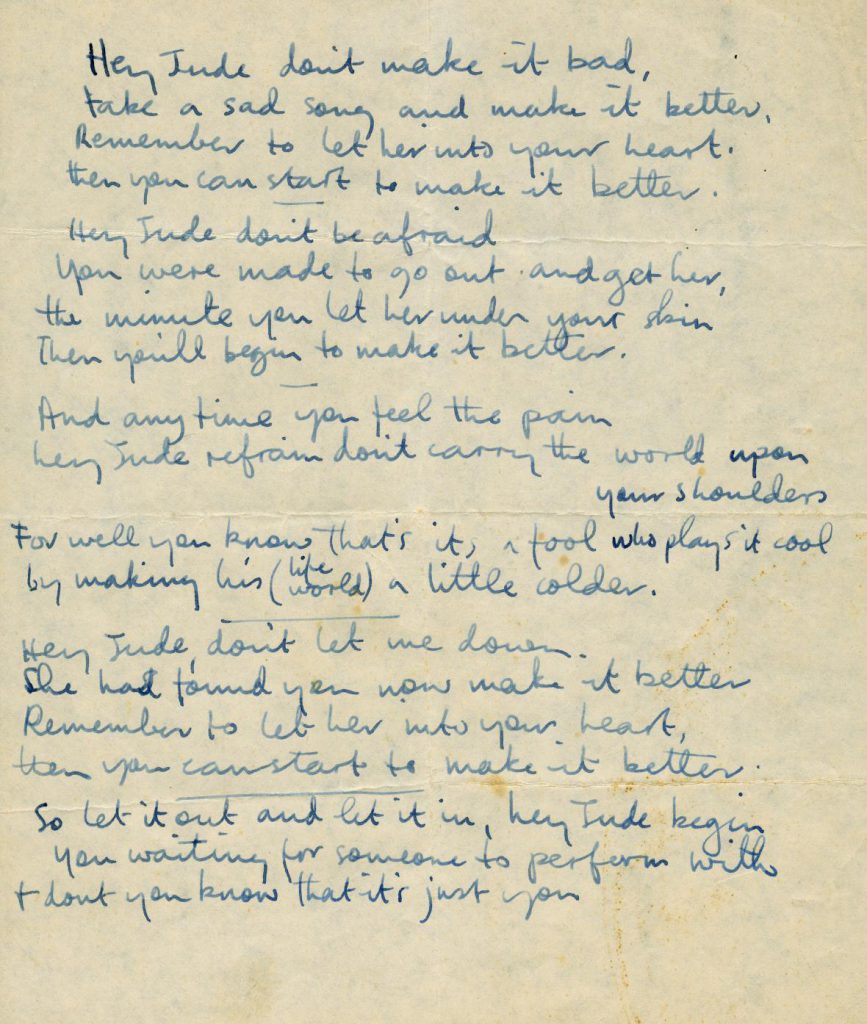

I started with the idea “Hey Jules,” which was Julian, don’t make it bad, take a sad song and make it better. Hey, try and deal with this terrible thing. I knew it was not going to be easy for him. I always feel sorry for kids in divorces …

Paul McCartney – from “Paul McCartney: Many Years From Now” by Barry Miles, 1997

From Wikipedia:

“Hey Jude” is a song by the English rock band the Beatles that was released as a non-album single in August 1968. It was written by Paul McCartney and credited to the Lennon–McCartney partnership. The single was the Beatles’ first release on their Apple record label and one of the “First Four” singles by Apple’s roster of artists, marking the label’s public launch. “Hey Jude” was a number-one hit in many countries around the world and became the year’s top-selling single in the UK, the US, Australia and Canada. Its nine-week run at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 tied the all-time record in 1968 for the longest run at the top of the US charts, a record it held for nine years. It has sold approximately eight million copies and is frequently included on music critics’ lists of the greatest songs of all time.

The writing and recording of “Hey Jude” coincided with a period of upheaval in the Beatles. The ballad evolved from “Hey Jules”, a song McCartney wrote to comfort John Lennon’s son, Julian, after Lennon had left his wife for the Japanese artist Yoko Ono. The lyrics espouse a positive outlook on a sad situation, while also encouraging “Jude” to pursue his opportunities to find love. After the fourth verse, the song shifts to a coda featuring a “Na-na-na na” refrain that lasts for over four minutes.

“Hey Jude” was the first Beatles song to be recorded on eight-track recording equipment. The sessions took place at Trident Studios in central London, midway through the recording of the group’s self-titled double album (also known as the “White Album”), and led to an argument between McCartney and George Harrison over the song’s guitar part. Ringo Starr later left the band only to return shortly before they filmed the promotional clip for the single. The clip was directed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg and first aired on David Frost’s UK television show. Contrasting with the problems afflicting the band, this performance captured the song’s theme of optimism and togetherness by featuring the studio audience joining the Beatles as they sang the coda.

At over seven minutes in length, “Hey Jude” was the longest single to top the British charts up to that time. Its arrangement and extended coda encouraged many imitative works through to the early 1970s. In 2013, Billboard magazine named it the 10th “biggest” song of all time in terms of chart success. McCartney has continued to perform “Hey Jude” in concert since Lennon’s death in 1980, leading audiences in singing the coda. Julian Lennon and McCartney have each bid successfully at auction for items of memorabilia related to the song’s creation.

Inspiration and writing

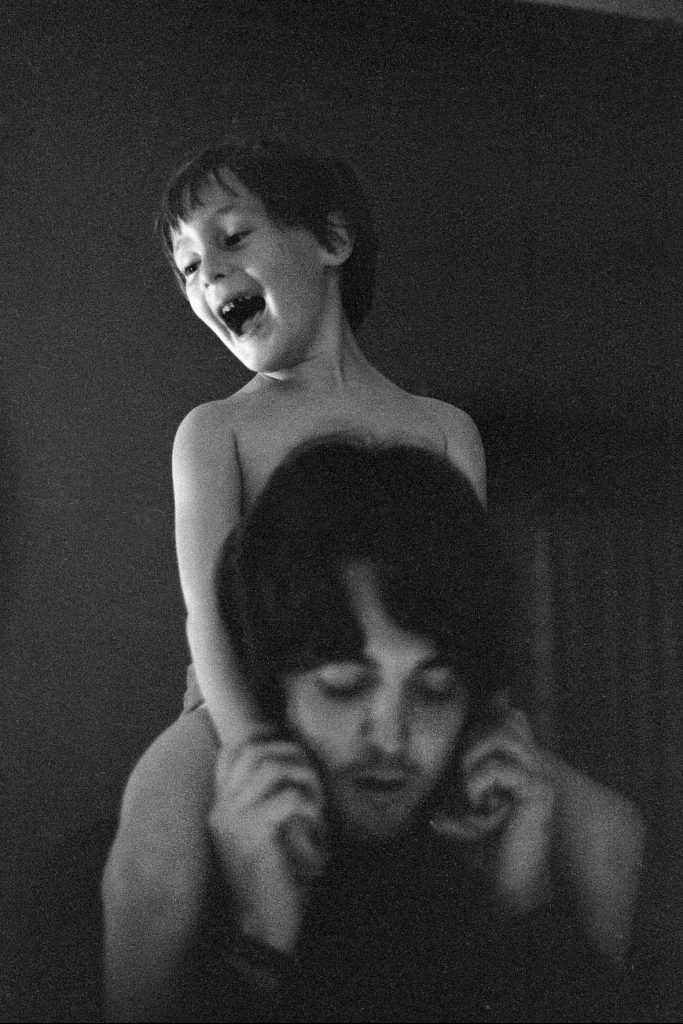

In May 1968, John Lennon and his wife Cynthia separated due to his affair with Japanese artist Yoko Ono. The following month, Paul McCartney drove out to visit the Lennons’ five-year-old son Julian, at Kenwood, the family’s home in Weybridge. Cynthia had been part of the Beatles’ social circle since before the band’s rise to fame in 1963; McCartney later said he found it “a bit much for them suddenly to be personae non gratae and out of my life”. Cynthia Lennon recalled of McCartney’s surprise visit: “I was touched by his obvious concern for our welfare … On the journey down he composed ‘Hey Jude’ in the car. I will never forget Paul’s gesture of care and concern in coming to see us.” The song’s original title was “Hey Jules”, and it was intended to comfort Julian from the stress of his parents’ separation. McCartney said, “I knew it was not going to be easy for him”, and that he changed the name to “Jude” “because I thought that sounded a bit better”.

According to music journalist Chris Hunt, in the weeks after writing the song, McCartney “test[ed] his latest composition on anyone too polite to refuse. And that meant everyone.” On 30 June, after recording the Black Dyke Mills Band’s rendition of his instrumental “Thingumybob” in Yorkshire, McCartney stopped at the village of Harrold in Bedfordshire and performed “Hey Jude” at a local pub. He also regaled members of the Bonzo Dog Band with the song while producing their single “I’m the Urban Spaceman“, in London, and interrupted a recording session by the Barron Knights to do the same. Ron Griffith of the group the Iveys – soon to be known as Badfinger and, like the Black Dyke Mills Band, an early signing to the Beatles’ new record label Apple Records – recalled that on one of their first days in the studio, McCartney “gave us a full concert rendition of ‘Hey Jude'”.

The intensity of Lennon and Ono’s relationship made any songwriting collaboration between Lennon and McCartney impossible. Keen to support his friend nevertheless, McCartney let the couple stay at his house in St John’s Wood, but when Lennon discovered a note written by McCartney containing disparaging and racist comments about Ono, the couple moved out. McCartney presented “Hey Jude” to Lennon on 26 July, when he and Ono visited McCartney’s home. McCartney assured him that he would “fix” the line “the movement you need is on your shoulder”, reasoning that “it’s a stupid expression; it sounds like a parrot.” According to McCartney, Lennon replied: “You won’t, you know. That’s the best line in the song.” McCartney retained the phrase. Although McCartney originally wrote “Hey Jude” for Julian, Lennon thought it had actually been written for him. In a 1980 interview, Lennon stated that he “always heard it as a song to me” and contended that, on one level, McCartney was giving his blessing to Lennon and Ono’s relationship, while, on another, he was disappointed to be usurped as Lennon’s friend and creative partner.

Other people believed McCartney wrote the song about them, including Judith Simons, a journalist with the Daily Express. Still others, including Lennon, have speculated that in the lyrics to “Hey Jude”, McCartney’s failing long-term relationship with Jane Asher provided an unconscious “message to himself”. McCartney and Asher had announced their engagement on 25 December 1967, yet he began an affair with Linda Eastman in June 1968; that same month, Francie Schwartz, an American who was in London to discuss a film proposal with Apple, began living with McCartney in St John’s Wood. When Lennon mentioned that he thought the song was about him and Ono, McCartney denied it and told Lennon he had written the song about himself.

Author Mark Hertsgaard has commented that “many of the song’s lyrics do seem directed more at a grown man on the verge of a powerful new love, especially the lines ‘you have found her now go and get her’ and ‘you’re waiting for someone to perform with.'” Music critic and author Tim Riley writes: “If the song is about self-worth and self-consolation in the face of hardship, the vocal performance itself conveys much of the journey. He begins by singing to comfort someone else, finds himself weighing his own feelings in the process, and finally, in the repeated refrains that nurture his own approbation, he comes to believe in himself.”

Production – EMI rehearsals

Having earmarked the song for release as a single, the Beatles recorded “Hey Jude” during the sessions for their self-titled double album, commonly known as “the White Album”. The sessions were marked by an element of discord within the group for the first time, partly as a result of Ono’s constant presence at Lennon’s side. The strained relations were also reflective of the four band members’ divergence following their communal trip to Rishikesh in the spring of 1968 to study Transcendental Meditation.

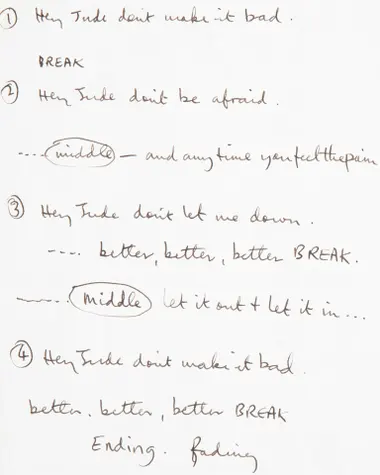

The Beatles first taped 25 takes of the song at EMI Studios in London over two nights, 29 and 30 July 1968, with George Martin as their producer. These dates served as rehearsals, however, since they planned to record the master track at Trident Studios to utilise their eight-track recording machine (EMI was still limited to four-tracks). The first two takes from 29 July, which author and critic Kenneth Womack describes as a “jovial” session, have been released on the 50th Anniversary box set of the White Album in 2018 and the Anthology 3 compilation in 1996, respectively.

The 30 July rehearsals were filmed for a short documentary titled Music!, which was produced by the National Music Council of Great Britain. This was the first time that the Beatles had permitted a camera crew to film them developing a song in the studio. The film shows only three of the Beatles performing “Hey Jude”, as George Harrison remained in the studio control room, with Martin and EMI recording engineer Ken Scott. During the rehearsals that day, Harrison and McCartney had a heated disagreement over the lead guitar part for the song. Harrison’s idea was to play a guitar phrase as a response to each line of the vocal, which did not fit with McCartney’s conception of the song’s arrangement, and he vetoed it. Author Simon Leng views this as indicative of how Harrison was increasingly allowed little room to develop ideas on McCartney compositions, whereas he was free to create empathetic guitar parts for Lennon’s songs of the period. In a 1994 interview, McCartney said, “looking back on it, I think, Okay. Well, it was bossy, but it was ballsy of me, because I could have bowed to the pressure.” Ron Richards, a record producer who worked for Martin at both Parlophone and AIR Studios, said McCartney was “oblivious to anyone else’s feelings in the studio”, and that he was driven to making the best possible record, at almost any cost.

Production – Trident Studios recording

The Beatles recorded the master track for “Hey Jude” at Trident, where McCartney and Harrison had each produced sessions for their Apple artists, on 31 July. Trident’s founder, Norman Sheffield, recalled that Mal Evans, the Beatles’ aide and former roadie, insisted that some marijuana plants he had brought be placed in the studio to make the place “soft”, consistent with the band’s wishes. Barry Sheffield served as recording engineer for the session. The line-up on the basic track was McCartney on piano and lead vocal, Lennon on acoustic guitar, Harrison on electric guitar, and Ringo Starr on drums. The Beatles recorded four takes of “Hey Jude”, the first of which was selected as the master. With drums intended to be absent for the first two verses, McCartney began this take unaware that Starr had just left for a toilet break. Starr soon returned – “tiptoeing past my back rather quickly”, in McCartney’s recollection – and performed his cue perfectly.

On 1 August, the group carried out overdubs on the basic track, again at Trident. These additions included McCartney’s lead vocal and bass guitar; backing vocals from Lennon, McCartney and Harrison; and tambourine, played by Starr. McCartney’s vocal over the long coda, starting at around three minutes into the song, included a series of improvised shrieks that he later described as “Cary Grant on heat!” They then added a 36-piece orchestra over the coda, scored by Martin. The orchestra consisted of ten violins, three violas, three cellos, two flutes, one contra bassoon, one bassoon, two clarinets, one contra bass clarinet, four trumpets, four trombones, two horns, percussion and two string basses. According to Norman Sheffield, there was dissension initially among the orchestral musicians, some of whom “were looking down their noses at the Beatles, I think”. Sheffield recalls that McCartney ensured their cooperation by demanding: “Do you guys want to get fucking paid or not?” During the first few takes, McCartney was unhappy about the lack of energy and passion in the orchestra’s performance, so he stood up on the grand piano and started conducting the musicians from there.

The Beatles then asked the orchestra members if they would clap their hands and sing along to the refrain in the coda. All but one of the musicians complied (for a double fee), with the abstainer reportedly saying, “I’m not going to clap my hands and sing Paul McCartney’s bloody song!” Apple Records assistant Chris O’Dell says she joined the cast of backing singers on the song; one of the label’s first signings, Jackie Lomax, also recalled participating.

“Hey Jude” was the first Beatles song to be recorded on eight-track equipment. Trident Studios were paid £25 per hour by EMI for the sessions. Sheffield said that the studio earned about £1,000 in total, but by having the Beatles record there, and in turn raving about the facility, the value was incalculable. The band carried out further work at Trident during 1968, and Apple artists such as Lomax, Mary Hopkin, Billy Preston and the Iveys all recorded there over the next year.

Mixing

Scott, Martin and the Beatles mixed the finished recording at Abbey Road. The transfer of the Trident master tape to acetate proved problematic due to the recording sounding murky when played back on EMI’s equipment. The issue was resolved with the help of Geoff Emerick, whom Scott had recently replaced as the Beatles’ principal recording engineer. Emerick happened to be visiting Abbey Road, having recently refused to work with the Beatles any longer, due to the tension and abuse that had become commonplace at their recording sessions. A stereo mix of “Hey Jude” was then completed on 2 August and the mono version on 8 August.

Musicologist Walter Everett writes that the song’s “most commented-on feature” is its considerable length, at 7:11. Like McCartney, Martin was concerned that radio stations would not play the track because of the length, but Lennon insisted: “They will if it’s us.” According to Ken Mansfield, Apple’s US manager, McCartney remained unconvinced until Mansfield previewed the record for some American disc jockeys and reported that they were highly enthusiastic about the song. “Hey Jude” was one second longer than Richard Harris’s recent hit recording of “MacArthur Park”, the composer of which, Jimmy Webb, was a visitor to the studio around this time. According to Webb, Martin admitted to him that “Hey Jude” was only allowed to run over seven minutes because of the success of “MacArthur Park”. Pleased with the result, McCartney played an acetate copy of “Hey Jude” at a party held by Mick Jagger, at Vesuvio’s nightclub in central London, to celebrate the completion of the Rolling Stones’ Beggars Banquet album. The song upstaged the Stones’ album and, in author John Winn’s description, “reportedly ruin[ed]” the party.

In the song’s final bridge section, at 2:58, the spoken phrase “Fucking hell!” appears, uttered by Lennon. Scott admits that although he was told about it, he could not hear the words originally. Malcolm Toft, the mix engineer on the Trident recording, recalled that Lennon was overdubbing his harmony vocal when, in reaction to the volume being too loud in his headphones, he first called out “Whoa!” then, two seconds later, swore as he pulled the headphones off.

Composition and structure

“Hey Jude” begins with McCartney singing lead vocals and playing the piano. The patterns he plays are based on three chords: F, C and B♭ (I, V and IV). The main chord progression is “flipped on its head”, in Hertsgaard’s words, for the coda, since the C chord is replaced by E♭. Everett comments that McCartney’s melody over the verses borrows in part from John Ireland’s 1907 liturgical piece Te Deum, as well as (with the first change to a B♭ chord) suggesting the influence of the Drifters’ 1960 hit “Save the Last Dance for Me”.

The second verse of the song adds accompaniment from acoustic guitar and tambourine. Tim Riley writes that, with the “restrained tom-tom and cymbal fill” that introduces the drum part, “the piano shifts downward to add a flat seventh to the tonic chord, making the downbeat of the bridge the point of arrival (‘And any time you feel the pain‘).” At the end of each bridge, McCartney sings a brief phrase (“Na-na-na na …”), supported by an electric guitar fill, before playing a piano fill that leads to the next verse. According to Riley, this vocal phrase serves to “reorient the harmony for the verse as the piano figure turns upside down into a vocal aside”. Additional musical details, such as tambourine on the third verse and subtle harmonies accompanying the lead vocal, are added to sustain interest throughout the four-verse, two-bridge song.

The verse-bridge structure persists for approximately three minutes, after which the band leads into a four-minute-long coda, consisting of nineteen rounds of the song’s double plagal cadence. During this coda, the rest of the band, backed by an orchestra that also provides backing vocals, repeats the phrase “Na-na-na na” followed by the words “hey Jude” until the song gradually fades out. In his analysis of the composition, musicologist Alan Pollack comments on the unusual structure of “Hey Jude”, in that it uses a “binary form that combines a fully developed, hymn-like song together with an extended, mantra-like jam on a simple chord progression”.

Riley considers that the coda’s repeated chord sequence (I–♭VII–IV–I) “answers all the musical questions raised at the beginnings and ends of bridges”, since “The flat seventh that posed dominant turns into bridges now has an entire chord built on it.” This three-chord refrain allows McCartney “a bedding … to leap about on vocally”, so he ad-libs his vocal performance for the rest of the song. In Riley’s estimation, the song “becomes a tour of Paul’s vocal range: from the graceful inviting tones of the opening verse, through the mounting excitement of the song itself, to the surging raves of the coda”.

Release

“Hey Jude” was released on a 7-inch single on 26 August 1968 in the United States and 30 August in the United Kingdom, backed with “Revolution” on the B-side. It was one of four singles issued simultaneously to launch Apple Records – the others being Mary Hopkin’s “Those Were the Days“, Jackie Lomax’s “Sour Milk Sea“, and the Black Dyke Mills Band’s “Thingumybob”. In advance of the release date, Apple declared 11–18 August to be “National Apple Week” in the UK, and sent gift-wrapped boxes of the records, marked “Our First Four”, to Queen Elizabeth II and other members of the royal family, and to Harold Wilson, the prime minister. The release was promoted by Derek Taylor, who, in author Peter Doggett’s description, “hyped the first Apple records with typical elan”. “Hey Jude” was the first of the four singles, since it was still designated as an EMI/Parlophone release in the UK and a Capitol release in the US, but with the Apple Records logo now added. In the US, “Hey Jude” was the first Capitol-distributed Beatles single to be issued without a picture sleeve. Instead, the record was presented in a black sleeve bearing the words “The Beatles on Apple”.

Author Philip Norman comments that aside from “Sour Milk Sea”, which Harrison wrote and produced, the first Apple A-sides were all “either written, vocalised, discovered or produced” by McCartney. Lennon wanted “Revolution” to be the A-side of the Beatles single, but his bandmates opted for “Hey Jude”. In his 1970 interview with Rolling Stone, he said “Hey Jude” was worthy of an A-side, “but we could have had both.” In 1980, he told Playboy he still disagreed with the decision.

Doggett describes “Hey Jude” as a song that “glowed with optimism after a summer that had burned with anxiety and rage within the group and in the troubled world beyond”. The single’s release coincided with the violent subjugation of Vietnam War protestors at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, and condemnation in the West of the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia and its crushing of attempts to introduce democratic reforms there. In this climate, Lennon’s espousal of a pacifist agenda over violent confrontation in “Revolution” drew heavy criticism from New Left activists. By contrast, with its more universal message, “Hey Jude” was adopted as an anthem by Czech citizens in their struggle.

The song was first released on an album in February 1970, as the title track to Capitol’s North American compilation Hey Jude. The album was conceived as a way to generate income for the Beatles by Allen Klein, the American businessman who, despite McCartney’s strong opposition, the other Beatles had appointed to manage the ailing Apple organisation in 1969. “Hey Jude” subsequently appeared on the compilation albums 1967–1970, 20 Greatest Hits, Past Masters, Volume Two and 1.

Promotion – Apple shop window graffiti

A failed early promotional attempt for the single took place after the Beatles’ all-night recording session on 7–8 August 1968. With Apple Boutique having closed a week before, McCartney and Francie Schwartz painted Hey Jude/Revolution across its large, whitewashed shop windows. The words were mistaken for antisemitic graffiti (since Jude means “Jew” in German), leading to complaints from the local Jewish community, and the windows being smashed by a passer-by.

Discussing the episode in The Beatles Anthology, McCartney explained that he had been motivated by the location – “Great opportunity. Baker Street, millions of buses going around …” – and added: “I had no idea it meant ‘Jew’, but if you look at footage of Nazi Germany, ‘Juden Raus‘ was written in whitewashed windows with a Star of David. I swear it never occurred to me.” According to Barry Miles, McCartney caused further controversy in his comments to Alan Smith of the NME that month, when, in an interview designed to promote the single, he said: “Starvation in India doesn’t worry me one bit, not one iota … And it doesn’t worry you, if you’re honest. You just pose.”

Promotion – Promotional film

The Beatles hired Michael Lindsay-Hogg to shoot promotional clips for “Hey Jude” and “Revolution”, after he had previously directed the clips for “Paperback Writer” and “Rain” in 1966. For “Hey Jude”, they settled on the idea of shooting with a live, albeit controlled, audience. In the clip, the Beatles are first seen by themselves, performing the initial chorus and verses, before the audience moves forward and joins them in singing the coda. The decision was made to hire an orchestra and for the vocals to be sung live, to circumvent the Musicians’ Union’s ban on miming on television, but otherwise the Beatles performed to a backing track. Lindsay-Hogg shot the clip at Twickenham Film Studios on 4 September 1968. Tony Bramwell, a friend of the Beatles, later described the set as “the piano, there; drums, there; and orchestra in two tiers at the back.” The event marked Starr’s return to the group, after McCartney’s criticism of his drumming had led to him walking out during a session for the White Album track “Back in the U.S.S.R.” Starr was absent for two weeks.

The final edit was a combination of two different takes and included “introductions” to the song by David Frost (who introduced the Beatles as “the greatest tea-room orchestra in the world”) and Cliff Richard, for their respective TV programmes. It first aired in the UK on Frost on Sunday on 8 September 1968, two weeks after Lennon and Ono had appeared on the show to promote their views on performance art and the avant-garde. The “Hey Jude” clip was broadcast in the United States on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour on 6 October.

According to Riley, the Frost on Sunday broadcast “kicked ‘Hey Jude’ into the stratosphere” in terms of popularity. Norman comments that it evoked “palpable general relief” for viewers who had watched Frost’s show two weeks before, as Lennon now adopted a supporting role to McCartney, and Ono was “nowhere in sight”. Hertsgaard pairs the band’s performance with the release of the animated film Yellow Submarine as two events that created “a state of nirvana” for Beatles fans, in contrast with the problems besetting the band regarding Ono’s influence and Apple. Referring to the sight of the Beatles engulfed by a crowd made up of “young, old, male, female, black, brown, and white” fans, Hertsgaard describes the promotional clip as “a quintessential sixties moment, a touching tableau of contentment and togetherness”.

The 4 September 1968 promo clip is included in the Beatles’ 2015 video compilation 1, while the three-disc versions of that compilation, titled 1+, also include an alternate video, with a different introduction and vocal, from the same date.

Commercial performance

The single was a highly successful debut for Apple Records, a result that contrasted with the public embarrassment the band faced after the recent closure of their short-lived retail venture, Apple Boutique. In the description of music journalist Paul Du Noyer, the song’s “monumental quality … amazed the public in 1968”; in addition, the release silenced detractors in the British mainstream press who had relished the opportunity to criticise the band for their December 1967 television special, Magical Mystery Tour, and their trip to Rishikesh in early 1968. In the US, the single similarly brought an end to speculation that the Beatles’ popularity might be diminishing, after “Lady Madonna” had peaked at number 4.

“Hey Jude” reached the top of Britain’s Record Retailer chart (subsequently adopted as the UK Singles Chart) in September 1968. It lasted two weeks on top before being replaced by Hopkin’s “Those Were the Days”, which McCartney helped promote. “Hey Jude” was certified gold by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) on 13 September; that same week, NME reported that two million copies of the single had been sold. The song entered the Billboard Hot 100 in the US on 14 September, beginning a nineteen-week chart run there. It reached number one on 28 September and held that position for nine weeks, for three of which “Those Were the Days” held the number-two spot. This was the longest run at number one for a single in the US until 1977. The song was the 16th number-one hit there for the Beatles. Billboard ranked it as the number-one song for 1968. In Australia, “Hey Jude” was number one for 13 weeks, which remained a record there until Abba’s “Fernando” in 1976. It also topped the charts in Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, France, Ireland, Malaysia, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, the Philippines, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and West Germany.

On 30 November 1968, NME reported that sales had reached nearly six million copies worldwide. By 1999, “Hey Jude” had sold an estimated eight million copies worldwide. That year, it was certified 4x platinum by the RIAA, representing four million units shipped in the US. As of December 2018, “Hey Jude” was the 54th best-selling single of all time in the UK – one of six Beatles songs included on the top sales rankings published by the Official Charts Company.

Critical reception

In his contemporary review of the single, Derek Johnson of the NME wrote: “The intriguing features of ‘Hey Jude’ are its extreme length and the 40-piece orchestral accompaniment – and personally I would have preferred it without either!” While he viewed the track overall as “a beautiful, compelling song”, and the first three minutes as “absolutely sensational”, Johnson rued the long coda’s “vocal improvisations on the basically repetitive four-bar chorus”. Johnson nevertheless concluded that “Hey Jude” and “Revolution” “prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that the Beatles are still streets ahead of their rivals”. Chris Welch of Melody Maker said he had initially been unimpressed, but came to greatly admire “Hey Jude” for its “slow, heavy, piano-ridden beat, sensuous, soulful vocals and nice thumpy drums”. He added that the track would have benefited from being edited in length, as the climactic ending was “a couple of minutes too long”.

Cash Box‘s reviewer said that the extended fadeout, having been a device pioneered by the Beatles on “All You Need Is Love“, “becomes something of an art form” in “Hey Jude”, comprising a “trance-like ceremonial that becomes almost timeless in its continuity”. Time magazine described it as “a fadeout that engagingly spoofs the fadeout as a gimmick for ending pop records”. The reviewer contrasted “Hey Jude” with “Revolution”, saying that McCartney’s song “urges activism of a different sort” by “liltingly exhort[ing] a friend to overcome his fears and commit himself in love”. Catherine Manfredi of Rolling Stone also read the lyrics as a message from McCartney to Lennon to end his negative relationships with women: “to break the old pattern; to really go through with love”. Manfredi commented on the duality of the song’s eponymous protagonist as a representation of good, in Saint Jude, “the Patron of that which is called Impossible”, and of evil, in Judas Iscariot. Other commentators interpreted “Hey Jude” as being directed at Bob Dylan, then semi-retired in Woodstock.

Writing in 1971, Robert Christgau of The Village Voice called it “one of [McCartney’s] truest and most forthright love songs” and said that McCartney’s romantic side was ill-served by the inclusion of “‘I Will‘, a piece of fluff” on The Beatles. In their 1975 book The Beatles: An Illustrated Record, critics Roy Carr and Tony Tyler wrote that “Hey Jude” “promised great things” for the ill-conceived Apple enterprise and described the song as “the last great Beatles single recorded specifically for the 45s market”. They commented also that “the epic proportions of the piece” encouraged many imitators, yet these other artists “[failed] to capture the gentleness and sympathy of the Beatles’ communal feel”. Walter Everett admires the melody as a “marvel of construction, contrasting wide leaps with stepwise motions, sustained tones with rapid movement, syllabic with melismatic word-setting, and tension … with resolution”. He cites Van Morrison’s “Astral Weeks”, Donovan’s “Atlantis”, the Moody Blues’ “Never Comes the Day” and the Allman Brothers’ “Revival” among the many songs with “mantralike repeated sections” that followed the release of “Hey Jude”. In his entry for the song in his 1993 book Rock and Roll: The 100 Best Singles, Paul Williams describes it as a “song about breathing”. He adds: “‘Hey Jude’ kicks ass like Van Gogh or Beethoven in their prime. It is, let’s say, one of the wonders of this corner of creation … It opens out like the sky at night or the idea of the existence of God.”

Alan Pollack highlights the song as “such a good illustration of two compositional lessons – how to fill a large canvas with simple means, and how to use diverse elements such as harmony, bassline, and orchestration to articulate form and contrast.” Pollack says that the long coda provides “an astonishingly transcendental effect”, while AllMusic’s Richie Unterberger similarly opines: “What could have very easily been boring is instead hypnotic because McCartney varies the vocal with some of the greatest nonsense scatting ever heard in rock, ranging from mantra-like chants to soulful lines to James Brown power screams.” In his book Revolution in the Head, Ian MacDonald wrote that the “pseudo-soul shrieking in the fade-out may be a blemish” but he praised the song as “a pop/rock hybrid drawing on the best of both idioms”. MacDonald concluded: “‘Hey Jude’ strikes a universal note, touching on an archetypal moment in male sexual psychology with a gentle wisdom one might properly call inspired.” Lennon said the song was “one of [McCartney’s] masterpieces”.

Awards and accolades

“Hey Jude” was nominated for the Grammy Awards of 1969 in the categories of Record of the Year, Song of the Year and Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocal, but failed to win any of them. In the 1968 NME Readers’ Poll, “Hey Jude” was named the best single of the year, and the song also won the 1968 Ivor Novello Award for “A-Side With the Highest Sales”. “Hey Jude” was inducted into the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences Grammy Hall of Fame in 2001 and it is one of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s “500 Songs That Shaped Rock & Roll”.

In 2004, Rolling Stone ranked “Hey Jude” at number eight on the “500 Greatest Songs of All Time”, making it the highest-placed Beatles song on the list. Among its many appearances in other best-song-of-all-time lists, VH1 placed it ninth in 2000 and Mojo ranked it at number 29 in the same year, having placed the song seventh in a 1997 list of “The 100 Greatest Singles of All Time”. In 1976, the NME ranked it 38th on the magazine’s “Top 100 Singles of All Time”, and the track appeared at number 77 on the same publication’s “The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time” in 2014. In January 2001, “Hey Jude” came in third on Channel 4’s list of the “100 Greatest Singles”. The Amusement & Music Operators Association ranks “Hey Jude” as the 11th-best jukebox single of all time. In 2008, the song appeared in eighth place on Billboard‘s “All Time Hot 100 Songs”.

In July 2006, Mojo placed “Hey Jude” at number 12 on its list of “The 101 Greatest Beatles Songs”. On a similar list compiled four years later, Rolling Stone ranked the song at number seven. In 2015, the ITV program The Nation’s Favourite Beatles Number One ranked “Hey Jude” in first place. In 2018, the music staff of Time Out London ranked it at number 49 on their list of the best Beatles songs. Writing in the magazine, Nick Levine said: “Don’t allow yourself to overlook this song because of its sheer ubiquity … ‘Hey Jude’ is a huge-hearted, super-emotional epic that climaxes with one of pop’s most legendary hooks.”

Auctioned lyrics and memorabilia

In his 1996 article about the single’s release, for Mojo, Paul Du Noyer said that the writing of “Hey Jude” had become “one of the best-known stories in Beatles folklore”. In a 2005 interview, Ono said that for McCartney and for Julian and Cynthia Lennon, the scenario was akin to a drama, in that “Each person has something to be totally miserable about, because of the way they were put into this play. I have incredible sympathy for each of them.” Du Noyer quoted Cynthia Lennon as saying of “Hey Jude”, “it always bring tears to my eyes, that song.”

Julian discovered that “Hey Jude” had been written for him almost 20 years after the fact. He recalled of his and McCartney’s relationship: “Paul and I used to hang about quite a bit – more than Dad and I did. We had a great friendship going and there seems to be far more pictures of me and Paul playing together at that age than there are pictures of me and my dad.” In 1996, Julian paid £25,000 for the recording notes to “Hey Jude” at an auction. He spent a further £35,000 at the auction, buying John Lennon memorabilia. John Cousins, Julian Lennon’s manager, stated at the time: “He has a few photographs of his father, but not very much else. He is collecting for personal reasons; these are family heirlooms if you like.”

In 2002, the original handwritten lyrics for the song were nearly auctioned off at Christie’s in London. The sheet of notepaper with the scrawled lyrics had been expected to fetch up to £80,000 at the auction, which was scheduled for 30 April 2002. McCartney went to court to stop the auction, claiming the paper had disappeared from his West London home. Richard Morgan, representing Christie’s, said McCartney had provided no evidence that he had ever owned the piece of paper on which the lyrics were written. The courts decided in McCartney’s favour and prohibited the sale of the lyrics. They had been sent to Christie’s for auction by Frenchman Florrent Tessier, who said he purchased the piece of paper at a street market stall in London for £10 in the early 1970s. In the original catalogue for the auction, Julian Lennon had written, “It’s very strange to think that someone has written a song about you. It still touches me.”

Along with “Yesterday“, “Hey Jude” was one of the songs that McCartney has highlighted when attempting to have some of the official Beatles songwriting credits changed to McCartney–Lennon. McCartney applied the revised credit to this and 18 other Lennon–McCartney songs on his 2002 live album Back in the U.S., attracting criticism from Ono, as Lennon’s widow, and from Starr, the only other surviving member of the Beatles.

Cover versions and McCartney live performances

In 1968, R&B singer Wilson Pickett released a cover recorded at Muscle Shoals Sound Studio, with a guitar part played by a young Duane Allman, who recommended the song to Pickett. Eric Clapton commented, “I remember hearing [it] and calling either Ahmet Ertegun or Tom Dowd and saying, ‘Who’s that guitar player?’ … To this day, I’ve never heard better rock guitar playing on an R&B record. It’s the best.” Session musician Jimmy Johnson, who played on the recording, said that Allman’s solo “created Southern rock”.

“Hey Jude” was one of the few Beatles songs that Elvis Presley covered, when he rehearsed the track at his 1969 Memphis sessions with producer Chips Moman, a recording that appeared on the 1972 album Elvis Now. A medley of “Yesterday” and “Hey Jude” was included on the 1999 reissue of Presley’s 1970 live album On Stage. Katy Perry performed “Hey Jude” as part of the 2012 MusiCares Person of the Year concert honouring McCartney.

McCartney played “Hey Jude” throughout his 1989–90 world tour, his first tour since Lennon’s murder in 1980. McCartney had considered including it as the closing song on his band Wings’ 1975 tours, but decided that “it just didn’t feel right.” He has continued to feature the song in his concerts, leading the audience in organised singalongs whereby different segments of the crowd – such as those in a certain section of the venue, then only men followed by only the women – chant the “Na-na-na na” refrain. McCartney sang the song in the closing moments of the opening ceremony of the 2012 Summer Olympics hosted in London. On 4 August 2012, McCartney led the crowd in a rendition of “Hey Jude” while watching cycling at the velodrome. […]

Paul McCartney in "Many Years From Now", by Barry Miles:

I finished it all up in Cavendish and I was in the music room upstairs when John and Yoko came to visit and they were right behind me over my right shoulder, standing up, listening to it as I played it to them, and when I got to the line, ‘The movement you need is on your shoulder,’ I looked over my shoulder and I said, ‘I’ll change that, it’s a bit crummy. I was just blocking it out,’ and John said, ‘You won’t, you know. That’s the best line in it!’ That’s collaboration. When someone’s that firm about a line that you’re going to junk, and he said, ‘No, keep it in.’ So of course you love that line twice as much because it’s a little stray, it’s a little mutt that you were about to put down and it was reprieved and so it’s more beautiful than ever. I love those words now…Time lends a little credence to things. You can’t knock it, it just did so well. But when I’m singing it, that is when I think of John, when I hear myself singing that line; it’s an emotional point in the song.

During the divorce proceedings, I was truly surprised when, one afternoon, Paul arrived on his own. I was touched by his obvious concern for our welfare and even more moved when he presented me with a single red rose accompanied by a jokey remark about our future. ‘How about it, Cyn. How about you and me getting married?’ We both laughed at the thought of the world’s reaction to an announcement like that being let loose. On his journey down to visit Julian and I, Paul composed the beautiful song ‘Hey Jude’. He said it was for Julian. I will never forget Paul’s gesture of care and concern in coming to see us. It made me feel important and loved, as opposed to feeling discarded and obsolete.

Cynthia Lennon – From “The Beatles: Off the Record” by Keith Badman

If you think about it … Yoko’s just come into the picture. He’s saying. “Hey, Jude – Hey, John.” I know I’m sounding like one of those fans who reads things into it, but you can hear it as a song to me. The words “Go out and get her” – subconsciously he was saying, Go ahead, leave me. On a conscious level, he didn’t want me to go ahead.

John Lennon, 1980 – From “All We Are Saying: The Last Major Interview with John Lennon and Yoko Ono” by David Sheff (2000)

We recorded ‘Hey Jude’ in Trident Studios. It was a long song. In fact, after I timed it I actually said, ‘You can’t make a single that long.’ I was shouted down by the boys – not for the first time in my life – and John asked: ‘Why not?’ I couldn’t think of a good answer, really – except the pathetic one that disc jockeys wouldn’t play it. He said, ‘They will if it’s us.’ And, of course, he was absolutely right.

George Martin, from Facebook

We liked the end. We liked it going on. The DJs can always fade it down if they want to. If you get fed up with it, you can always turn it over. You don’t always have to sit through it. A lot of people enjoy every second of the end and there really isn’t much repetition in it.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles: Off the Record” by Keith Badman

I was worried stiff when ‘Hey Jude’ came out, just in case it wasn’t any good. I wasn’t sure if it was any good. I can never tell.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles: Off the Record” by Keith Badman

The first time I played this song for John and Yoko was on what we called the “Magic Piano” in my music room. I was facing one way, and they were standing behind me almost on my shoulder. So when I sang, “The movement you need is on your shoulder”, I immediately turned around to John and said, “Don’t worry, I’ll change that,” and he looked at me and said, “You won’t, you know. It’s the best line in it.” So, this line that I was going to junk got to stay in. It’s a great example of how we collaborated. He was so firm about keeping it in that when I sing Hey Jude now, I often think of John, and it’s become this emotional point in the song for me. It was a delicate moment, of course, because I’m not even sure he knew at the time that the song was for his son Julian.

The song had started when I was travelling out one day to see Julian and his mother, Cynthia. At this point John had left Cynthia, and I was going out to Kenwood as a friend to say hi and see how they were doing. People have suggested I fancied Cynthia, as people will, but that’s not at all the case. I was thinking about how tough it would be for Jules, as I called him, to have his dad leave him, to have his parents go through a divorce. It started out as a song of encouragement. What often happens with a song is that it starts off in one vein — in this case my being worried about something in life, a specific thing like a divorce — but then it begins to morph into its own creature. The title early on was Hey Jules, but it quickly changed to Hey Jude because I thought that was a bit less specific. I realised no one would know exactly what this was about, so I might just as well open it up a bit. Ironically, for a time John thought it was about him and my giving permission for him to be with Yoko: “You have found her, now go and get her”. I didn’t ever know a person called Jude. It was a name I liked — partly, I believe, because of Pore Jud Is Daid, that plaintive song from Oklahoma! What happens next is that I start adding elements.

When I write, “You were made to go out and get her”, there’s now another character, a woman, in the scene. So it might now be a song about a break-up or some romantic mishap. By this stage the song has moved on from being about Julian. It could now be about this new woman’s relationship. I like my songs to have an everyman or everywoman element. Another element that was added to the song is the refrain. Hey Jude wasn’t meant to be that length, but we were having such fun ad-libbing at the end that it turned into an anthem, and the orchestra gets built up and built up partly because it has the time to do that. A funny thing happened in the studio during the recording. Thinking everyone was ready, I started the song, but Ringo had run off to the toilet. Then, as we were recording, I felt him tiptoe back in behind me, and he got to his kit just in time to hit his intro without missing a beat. So even as we’re recording it, I’m thinking, “This is the take, and you put a little more into it.” We were having so much fun that we even left in the swearing around halfway through, when I made a mistake on the piano part. You have to listen carefully to hear it, but it’s there.

Paul McCartney – From Paul McCartney on his lyrics: ‘Eroticism was a driving force behind everything I wrote’ | Times2 | The Times– From “The Lyrics”, 2021

From The Usenet Guide to Beatles Recording Variations:

[a] mono 8 Aug 1968.

UK: Apple R5722 single 1968.

US: Apple 2276 single 1968.

CD: EMI single 1989.[b] stereo 5 Dec 1969.

US: Apple SW 385 Hey Jude 1970, Apple SKBO-3404 The Beatles 1967-1970 1973.

UK: Apple PCS P718 The Beatles 1967-1970 1973.

CD: EMI CDP 7 90044 2 Past Masters 2 1988, EMI CDP 7 97039 2 The Beatles 1967-1970 1993.Drums are mixed louder in stereo [b]. Mono [a] is 5 seconds longer than the longest appearance of [b], long fade. This song has appeared with early fades on some compilations (in stereo).

Hey Jude, don't make it bad

Take a sad song and make it better

Remember to let her into your heart

Then you can start to make it better

Hey Jude, don't be afraid

You were made to go out and get her

The minute you let her under your skin

Then you begin to make it better

And anytime you feel the pain, hey Jude, refrain

Don't carry the world upon your shoulders

For well you know that it's a fool who plays it cool

By making his world a little colder

Nah nah nah nah nah nah nah nah nah

Hey Jude, don't let me down

You have found her, now go and get her

Remember to let her into your heart

Then you can start to make it better

So let it out and let it in, hey Jude, begin

You're waiting for someone to perform with

And don't you know that it's just you, hey Jude, you'll do

The movement you need is on your shoulder

Nah nah nah nah nah nah nah nah nah yeah

Hey Jude, don't make it bad

Take a sad song and make it better

Remember to let her under your skin

Then you'll begin to make it

Better better better better better better, oh

Nah nah nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah, hey Jude

Nah nah nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah, hey Jude

Nah nah nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah, hey Jude

Nah nah nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah, hey Jude

Nah nah nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah, hey Jude

Nah nah nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah, hey Jude

Nah nah nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah, hey Jude

Nah nah nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah, hey Jude

Nah nah nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah, hey Jude

Nah nah nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah, hey Jude

Nah nah nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah, hey Jude

Nah nah nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah, hey Jude

Nah nah nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah, hey Jude

Nah nah nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah, hey Jude

Nah nah nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah, hey Jude

Nah nah nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah, hey Jude

7" Single • Released in 1968

7:19 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Bass, Piano, Vocals Ringo Starr : Backing vocals, Drums, Tambourine John Lennon : Acoustic guitar, Backing vocals George Harrison : Backing vocals, Electric guitar George Martin : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer Barry Sheffield : Recording engineer Bill Jackman : Flute Unknown musician(s) : Bassoon, Contrabass clarinet, Contrabassoon, Four trombones, Four trumpets, One flute, One percussionist, Ten violins, Three violas, Two cellos, Two clarinets, Two double basses, Two french horns John Perry : Backing vocals Bobby Kok : Cello

Session Recording & overdubs: Jul 31, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Overdubs: Aug 01, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Mixing: Aug 08, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

LP • Released in 1970

7:12 • Studio version • B • Stereo

Paul McCartney : Bass, Piano, Vocals Ringo Starr : Backing vocals, Drums, Tambourine John Lennon : Acoustic guitar, Backing vocals George Harrison : Backing vocals, Electric guitar George Martin : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer Barry Sheffield : Recording engineer Bill Jackman : Flute Unknown musician(s) : Bassoon, Contrabass clarinet, Contrabassoon, Four trombones, Four trumpets, One flute, One percussionist, Ten violins, Three violas, Two cellos, Two clarinets, Two double basses, Two french horns John Perry : Backing vocals Bobby Kok : Cello

Session Recording & overdubs: Jul 31, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Overdubs: Aug 01, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Mixing: Dec 05, 1969 • Studio EMI Studios, Room 4, Abbey Road

Official album • Released in 1973

7:12 • Studio version • B

Paul McCartney : Bass, Piano, Vocals Ringo Starr : Backing vocals, Drums, Tambourine John Lennon : Acoustic guitar, Backing vocals George Harrison : Backing vocals, Electric guitar George Martin : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer Barry Sheffield : Recording engineer Bill Jackman : Flute Unknown musician(s) : Bassoon, Contrabass clarinet, Contrabassoon, Four trombones, Four trumpets, One flute, One percussionist, Ten violins, Three violas, Two cellos, Two clarinets, Two double basses, Two french horns John Perry : Backing vocals Bobby Kok : Cello

Session Recording & overdubs: Jul 31, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Overdubs: Aug 01, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Mixing: Dec 05, 1969 • Studio EMI Studios, Room 4, Abbey Road

LP • Released in 1973

7:12 • Studio version • B

Paul McCartney : Bass, Piano, Vocals Ringo Starr : Backing vocals, Drums, Tambourine John Lennon : Acoustic guitar, Backing vocals George Harrison : Backing vocals, Electric guitar George Martin : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer Barry Sheffield : Recording engineer Bill Jackman : Flute Unknown musician(s) : Bassoon, Contrabass clarinet, Contrabassoon, Four trombones, Four trumpets, One flute, One percussionist, Ten violins, Three violas, Two cellos, Two clarinets, Two double basses, Two french horns John Perry : Backing vocals Bobby Kok : Cello

Session Recording & overdubs: Jul 31, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Overdubs: Aug 01, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Mixing: Dec 05, 1969 • Studio EMI Studios, Room 4, Abbey Road

Hey Jude / Revolution (UK - 1976)

7" Single • Released in 1976

7:19 • Studio version • A • Mono

Paul McCartney : Bass, Piano, Vocals Ringo Starr : Backing vocals, Drums, Tambourine John Lennon : Acoustic guitar, Backing vocals George Harrison : Backing vocals, Electric guitar George Martin : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer Barry Sheffield : Recording engineer Bill Jackman : Flute Unknown musician(s) : Bassoon, Contrabass clarinet, Contrabassoon, Four trombones, Four trumpets, One flute, One percussionist, Ten violins, Three violas, Two cellos, Two clarinets, Two double basses, Two french horns John Perry : Backing vocals Bobby Kok : Cello

Session Recording & overdubs: Jul 31, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Overdubs: Aug 01, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Mixing: Aug 08, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Official album • Released in 1988

7:10 • Studio version • B • Stereo

Paul McCartney : Bass, Piano, Vocals Ringo Starr : Backing vocals, Drums, Tambourine John Lennon : Acoustic guitar, Backing vocals George Harrison : Backing vocals, Electric guitar George Martin : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer Barry Sheffield : Recording engineer Bill Jackman : Flute Unknown musician(s) : Bassoon, Contrabass clarinet, Contrabassoon, Four trombones, Four trumpets, One flute, One percussionist, Ten violins, Three violas, Two cellos, Two clarinets, Two double basses, Two french horns John Perry : Backing vocals Bobby Kok : Cello

Session Recording & overdubs: Jul 31, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Overdubs: Aug 01, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Mixing: Dec 05, 1969 • Studio EMI Studios, Room 4, Abbey Road

Hey Jude / Revolution (UK - 1988)

7" Single • Released in 1988

7:19 • Studio version • A

Paul McCartney : Bass, Piano, Vocals Ringo Starr : Backing vocals, Drums, Tambourine John Lennon : Acoustic guitar, Backing vocals George Harrison : Backing vocals, Electric guitar George Martin : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer Barry Sheffield : Recording engineer Bill Jackman : Flute Unknown musician(s) : Bassoon, Contrabass clarinet, Contrabassoon, Four trombones, Four trumpets, One flute, One percussionist, Ten violins, Three violas, Two cellos, Two clarinets, Two double basses, Two french horns John Perry : Backing vocals Bobby Kok : Cello

Session Recording & overdubs: Jul 31, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Overdubs: Aug 01, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Mixing: Aug 08, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Hey Jude / Revolution (UK - Picture disc - 1988)

7" Single • Released in 1988

7:19 • Studio version • A

Paul McCartney : Bass, Piano, Vocals Ringo Starr : Backing vocals, Drums, Tambourine John Lennon : Acoustic guitar, Backing vocals George Harrison : Backing vocals, Electric guitar George Martin : Producer Ken Scott : Recording engineer Barry Sheffield : Recording engineer Bill Jackman : Flute Unknown musician(s) : Bassoon, Contrabass clarinet, Contrabassoon, Four trombones, Four trumpets, One flute, One percussionist, Ten violins, Three violas, Two cellos, Two clarinets, Two double basses, Two french horns John Perry : Backing vocals Bobby Kok : Cello

Session Recording & overdubs: Jul 31, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Overdubs: Aug 01, 1968 • Studio Trident Studios, London, UK

Session Mixing: Aug 08, 1968 • Studio EMI Studios, Studio Two, Abbey Road

Tripping the Live Fantastic: Highlights!

Official live • Released in 1990

8:03 • Live • L1

Performed by : Paul McCartney • Linda McCartney • Robbie McIntosh • Hamish Stuart • Paul Wickens • Chris Whitten Paul McCartney : Producer Eddie Klein : Assistant engineer Matt Butler : Assistant engineer Peter Henderson : Producer Bob Clearmountain : Mixing engineer, Producer Jeff Cohen : Recording engineer Geoff Foster : Assistant engineer Scott Hull : Assistant engineer George Cowan : Assistant engineer Paul Rushbrook : Assistant engineer

Concert From the concert in Cincinnati, USA on Feb 12, 1990

Official live • Released in 1990

7:05 • Live • L6

Paul McCartney : Bass guitar, Guitar, Piano, Vocals Linda McCartney : Keyboards, Vocals Robbie McIntosh : Guitar, Vocals Hamish Stuart : Bass guitar, Guitar, Vocals Paul Wickens : Keyboards, Vocals Chris Whitten : Drums Chris Kimsey : Mixing engineer

Concert From "The Knebworth Festival - Silver Clef Award Winners Charity Concert" in Stevenage, United Kingdom on Jun 30, 1990

Unofficial live

10:16 • Live

Concert From the concert in Toronto, Canada on Jun 06, 1993

Unofficial live

7:05 • Live

Concert From the concert in Hamburg, Germany on Oct 03, 1989

Unofficial live

Driving USA Super Tree Volume 13 - Uniondale, NY 21 April 2002

Unofficial live

7:46 • Live

Concert From the concert in Uniondale, USA on Apr 21, 2002

Live at The Palace - Auburn Hills, Detroit MI May 1, 2002

Unofficial live

10:02 • Live

Concert From the concert in Detroit, USA on May 01, 2002

Concert Jul 11, 2009 in Halifax

Concert Nov 12, 2009 in London

Concert Dec 02, 2009 in Hamburg

Concert Dec 03, 2009 in Berlin

Concert Mar 30, 2010 in Los Angeles

Concert Aug 18, 2010 in Pittsburgh

Concert Dec 13, 2010 in New York

Concert May 19, 2016 in Buenos Aires

“Hey Jude” has been played in 669 concerts and 2 soundchecks.

Curitiba • Estádio Couto Pereira • Brazil

Dec 13, 2023 • Part of Got Back Tour

São Paulo • Allianz Parque • Brazil

Dec 10, 2023 • Part of Got Back Tour

São Paulo • Allianz Parque • Brazil

Dec 09, 2023 • Part of Got Back Tour

São Paulo • Allianz Parque • Brazil

Dec 07, 2023 • Part of Got Back Tour

Belo Horizonte • Mrv Arena • Brazil

Dec 04, 2023 • Part of Got Back Tour

The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present

"Hey Jude" is one of the songs featured in the book "The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present," published in 2021. The book explores Paul McCartney's early Liverpool days, his time with the Beatles, Wings, and his solo career. It pairs the lyrics of 154 of his songs with his first-person commentary on the circumstances of their creation, the inspirations behind them, and his current thoughts on them.

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.

[…] “Hey Jude,” which he played all the way through (the Beatles’ single version of the song was over 7 minutes long). “And of course, the people watching the clock are going absolutely apeshit,” Innes said. […]

[…] “Hey Jude,” which he played all the way through (the Beatles’ single version of the song was over 7 minutes long). “And of course, the people watching the clock are going absolutely apeshit,” Innes said. […]

[…] “Hey Jude,” which he played all the way through (the Beatles’ single version of the song was over 7 minutes long). “And of course, the people watching the clock are going absolutely apeshit,” Innes said. […]

[…] the divorce of his parents, John Lennon and Cynthia Lennon. However, the song has been marked as “a form of blessing” by Lennon himself for his and his new wife’s, Yoko Ono’s relationship, from Paul […]

[…] plants),希望樂隊可以得心應手,令錄製過程順風順水(in the studio to make the place “soft“)。大家終於搞清楚Hey Jude是甚麼意思,原來Hey Jude是指Julian […]

[…] plants),希望樂隊可以得心應手,令錄製過程順風順水(in the studio to make the place “soft“)。大家終於搞清楚Hey Jude是甚麼意思,原來Hey Jude是指Julian […]

5 Oldies in 60's,5首60年代經典金曲最後一擊:終章—傳承,更多傳奇的誕生 — CULTYELL • 3 years ago

[…] Hey Jude是The Beatles第一首以多軌錄音的歌曲,由不同音樂樂器演奏,歌曲一開始由Paul McCartney人聲及鋼琴帶領,之後不同樂器陸續加入,當中有大小提琴,喇叭及笛等樂器。而尾段,則哼出na—na—na超過4分鐘,在表演中引導觀眾唱這一段。有趣的地方是,The Beatles在Trident Studios錄音室錄音時,樂隊的助理及朋友Mal Evans堅持帶來一卡車的大麻植物(Marijuana plants),希望樂隊可以得心應手,令錄製過程順風順水(in the studio to make the place “soft“)。 […]

Hey Jude (1968) - The Beatles — CULTYELL • 3 years ago

[…] Hey Jude是The Beatles第一首以多軌錄音的歌曲,由不同音樂樂器演奏,歌曲一開始由Paul McCartney人聲及鋼琴帶領,之後不同樂器陸續加入,當中有大小提琴,喇叭及笛等樂器。而尾段,則哼出na—na—na超過4分鐘,在表演中引導觀眾唱這一段。有趣的地方是,The Beatles在Trident Studios錄音室錄音時,樂隊的助理及朋友Mal Evans堅持帶來一卡車的大麻植物(Marijuana plants),希望樂隊可以得心應手,令錄製過程順風順水(in the studio to make the place “soft“)。 […]