Sunday, June 25, 1967

Our World TV Broadcast: The Beatles' performance of "All You Need Is Love"

For The Beatles

Last updated on April 26, 2024

Sunday, June 25, 1967

For The Beatles

Last updated on April 26, 2024

Recording studio: EMI Studios, Studio One, Abbey Road

Session Jun 24, 1967 • Recording "All You Need Is Love" #4

Interview Jun 24, 1967 • Press conference for The Beatles' "Our World" performance

Session Jun 25, 1967 • Our World TV Broadcast: The Beatles' performance of "All You Need Is Love"

Film Jun 25, 1967 • Shooting of "All You Need Is Love" promo film

May 18, 1967 • The Beatles will participate in "Our World"

Jun 14, 1967 • Recording "All You Need Is Love" #1

June 17-22, 1967 • Mike Vickers writes the orchestra arrangement for "All You Need Is Love"

Jun 19, 1967 • Recording "All You Need Is Love" #2

Jun 21, 1967 • Mixing "All You Need Is Love"

Jun 23, 1967 • Recording "All You Need Is Love" #3

Jun 24, 1967 • Recording "All You Need Is Love" #4

Jun 24, 1967 • Press conference for The Beatles' "Our World" performance

Jun 25, 1967 • Our World TV Broadcast: The Beatles' performance of "All You Need Is Love"

Jun 25, 1967 • Shooting of "All You Need Is Love" promo film

Some of the songs worked on during this session were first released on the "All You Need Is Love / Baby You're A Rich Man (UK)" 7" Single.

On May 18, 1967, Brian Epstein signed a contract for The Beatles to appear as Britain’s representatives on “Our World”, a live television production that would be broadcast internationally via satellite on June 25. For this momentous occasion, The Beatles chose to record “All You Need Is Love”, a track written by John Lennon, and perform parts of it live.

The Beatles began recording “All You Need Is Love” on June 14, 1967, at Olympic Sound Studios, and continued working on it at EMI Studios, Abbey Road, on June 19. A mono mix was prepared on June 21, which was likely used as a reference for the orchestra’s scoring by George Martin.

On June 17, Mike Vickers, a member of Manfred Mann, was asked to write the orchestra arrangement, as George Martin had some personal constraints. Mike Vickers was also asked to conduct the orchestra during the rehearsals and live recordings, as George Martin would be busy producing the session on the day of the broadcast. He completed the writing of the score on June 22.

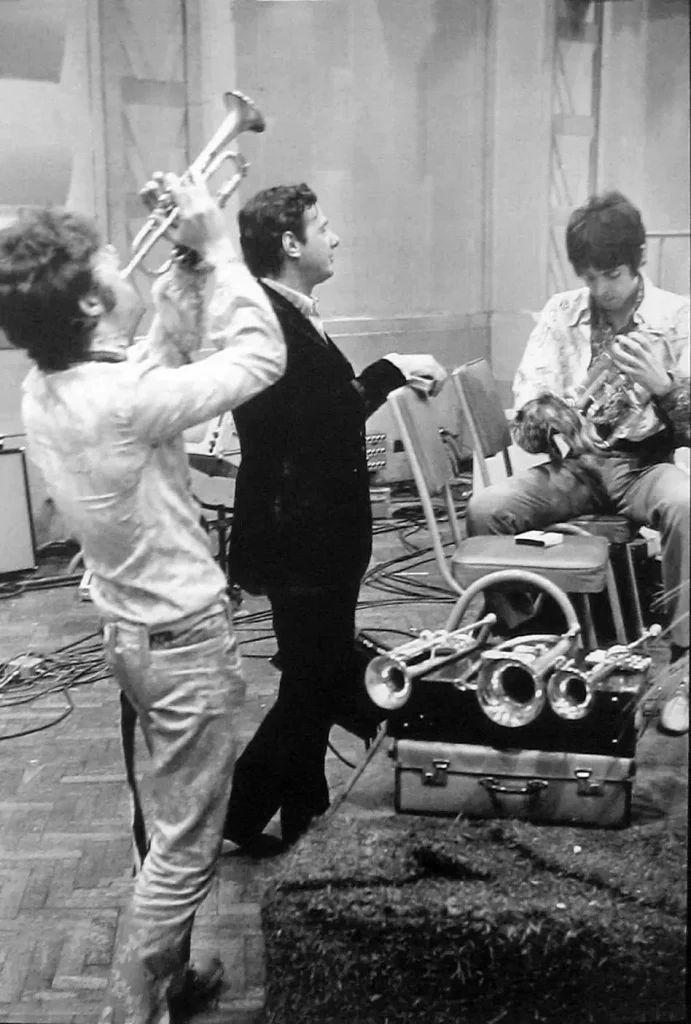

On June 23 and on June 24, The Beatles and the 13-piece orchestra, composed of four violins, two cellos, two tenor saxophones, two trombones, two trumpets, an accordion, and a flügelhorn, held their rehearsals at Abbey Road Studio 1.

On the day of the broadcast, June 25, The Beatles and the orchestra began rehearsals at 2 pm, which included testing the transmission with the BBC crew. The technical setup involved an outside broadcast van positioned in the EMI Studios car park, which transmitted the signal worldwide via the Intelsat I (Early Bird), Intelsat II (Lana Bird) and ATS-1 satellites.

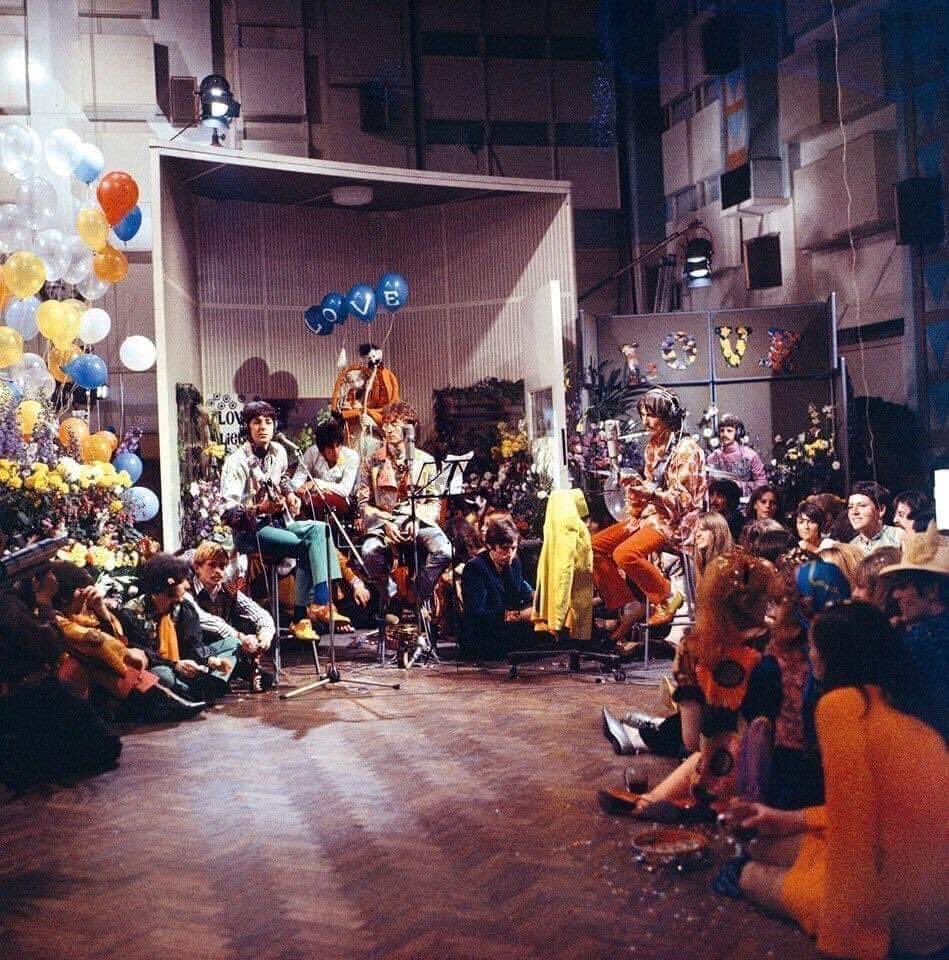

We started at 2pm on the Sunday, by which time, the studio was piled high with floral displays and balloons. The Beatles climbed into their garish psychedelic outfits and cameramen cursed as they cannoned into floral displays that hampered their tracking lines.

Steve Race – The show’s presenter – From “The Beatles: Off the Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

The live performance, recorded as Take 59, began at 8:54 pm London time, about 40 seconds earlier than expected. Producer George Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick were drinking scotch whisky to calm their nerves before mixing the audio for the live broadcast and had to hastily conceal the bottle and glasses under the mixing desk upon being informed they were about to go live.

The weekend rehearsals ground on for hours, but all too soon, it was Sunday afternoon. After completing a brief sound check, George Martin invited Richard and me to the Marble Arch town house he shared with his wife, Judy, so that we could relax for an hour or two before the evening’s broadcast. Judy made us lamb sandwiches, which was always a favorite of George’s. It was a nice gesture by the fraught producer, who was, like us, under a lot of pressure. Unfortunately, I don’t think it did much to steady our nerves. I just couldn’t wait for it to be over with!

When we returned to Abbey Road at around 6 p.m., the Beatles were already there, dressed in their finest Carnaby Street gear, and the tuxedoed musicians and celebrity guests—including Brian Epstein and various rock stars, wives, and girlfriends—were beginning to file in. There was a real party atmosphere, similar to what we had witnessed during previous Beatles “happenings,” but Richard and I were both struck by how visibly nervous John was, which was quite unusual for him: we’d never seen him wound up so tightly. He was smoking like a chimney and swigging directly from a pint bottle of milk, despite warnings from George Martin that it was bad for his voice—advice that Lennon studiously ignored. […] Paul was giving the outward appearance of being confident, but he had a strange, frozen smile planted on his face that betrayed the frayed nerves underneath. George and Ringo appeared to be the calmest of the four, though I could discern some tension in their body language as well. As the time of the broadcast drew closer and closer, you could almost sense the adrenaline as the nervous energy built in all of us.

Paul strode into the control room at one point and spent some time working on the bass sound with me. It struck me as a smart thing to do. Not only was he making certain that his instrument would come across the way he wanted it to, but getting out of the studio, away from the others and out of the line of fire, had a calming effect on both of us. It gave us both a little sanctuary where we could focus on just one specific thing and not think about the monumental technical feat we would soon be attempting to pull off.

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

Just before the broadcast was due to start, George and I decided to have a shot of Scotch for luck. Richard wanted to join us, but George said, “No, you’d better not.” He knew that Richard’s job was absolutely critical, because he had the task of playing back the tape with the backing track from one multitrack machine while simultaneously recording the live performance on another machine. If he screwed up and put the wrong machine in record, we would have a disaster on our hands!

Just as the glasses reached our lips, Murphy struck once again. “Going on air… NOW!” we heard over the intercom speaker unexpectedly. According to our clock, they were forty seconds early. But there was no time to argue or debate the matter. Instinctively, George and I went into a mad scramble to hide the bottle and glasses underneath the mixing console before the camera in the control room caught us imbibing. Fortunately, we were able to complete the operation seconds before the red light went on. Considering the last-minute panic, I thought George did a remarkable job of regaining his composure, looking dapper in his Casablanca-like white suit. After a moment’s pause while he received instructions from the BBC truck, he placed the talkback mic to his lips and said, “Ready, Geoff?”

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

Throughout the afternoon and early evening the musicians and technicians rehearsed constantly. It must have been the most rehearsed spontaneous performance ever! The party guests arrived…they sat on the studio floor and waited as the clock ticked remorselessly towards 9:30 pm, the time set for the live transmission. Despite the relaxing effects of the ‘whacky baccy’ being smoked throughout the studio and the building, tempers became frayed and nerves raw. Then John threw everything out of kilter by claiming that he had lost his voice. Paul laughed at him and gently ribbed his songwriting partner. A glass of water and a few more barbed comments from McCartney put things right.

Alistair Taylor – From “Hello Goodbye, The Story Of ‘Mr. Fixit’“, 2001

I was still standing around the control room with George Martin and Brian drinking whisky when we were told we were on the air, forty seconds early. We stuffed the bottle and glasses under the mixing desk and rushed into position. Mick [Jagger] sat on the floor near Paul and puffed on a massive reefer, in front of 200 million people — and he was due in court the next morning.

Tony Bramwell – From “Magical Mystery Tours: My Life with the Beatles“, 2005

The segment was directed by Derek Burrell-Davis, the head of the BBC’s “Our World” project. BBC presenter, Steve Race, introduced the group as the backing track played, and Derek Burrell-Davis then cut to the studio control room, from where George Martin instructed that the orchestra should be brought in.

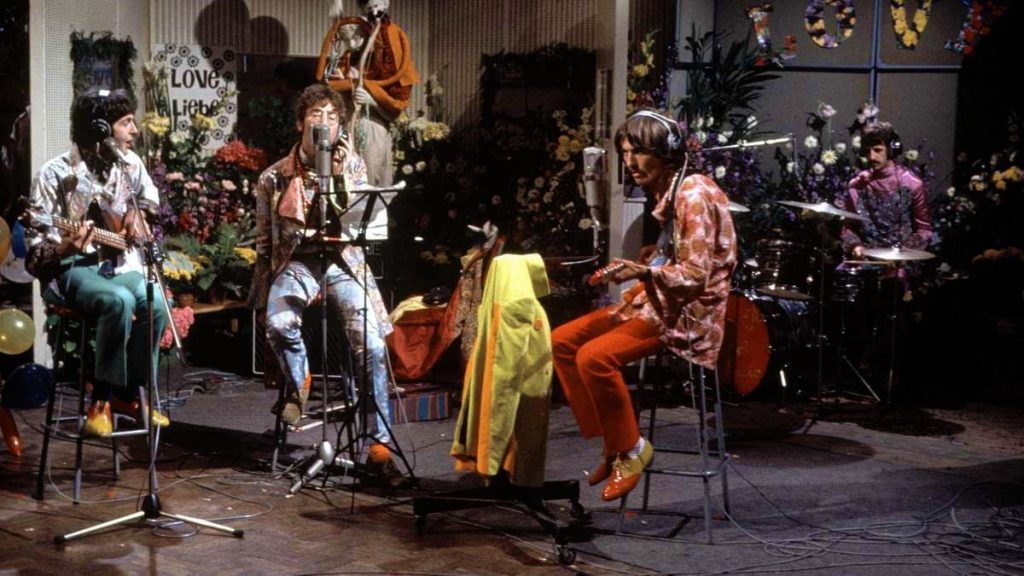

The Beatles were seated on high stools, except for Ringo Starr who was behind his drum kit. They were surrounded by friends and acquaintances seated on the floor, who sang along with the refrain during the fade-out. These guests included Mick Jagger, Eric Clapton, Marianne Faithfull, Keith Richards, Keith Moon, Graham Nash, Pattie Harrison (George’s wife), along with Mike McGear and Jane Asher (Paul’s brother and girlfriend, respectively).

The studio setting was designed to reflect the communal nature of the occasion and demonstrate the Beatles’ position of influence among their peers, particularly after the release of “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band“. Many of the invitations were extended through Beatles aides Mal Evans and Tony Bramwell, who visited various London nightclubs the previous night.

I got up and found Keith Moon quite easily at the Speakeasy. […] I trawled the Cromwellian, the Bag, the Scotch of St. James and found Eric Clapton, Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithful, and friends. Mick said he’d come, no hassle, but he was a bit put out that the BBC hadn’t asked the Stones. […] Eventually a reasonably sized party atmosphere was rounded up. Moon was early. Mick arrived wearing a beautiful silk coat with psychedelic eyes painted on it. Eppy came, looking very happy. He wore a black velvet suit but for once hadn’t put a tie on. It made him look fresh-faced and far younger. I took many photographs that day and those of Brian with the Beatles are the last ones ever taken of them together.

Tony Bramwell – From “Magical Mystery Tours: My Life with the Beatles“, 2005

I remember Mick Jagger arriving with this beautiful painted coat on, and Eric Clapton had just had his hair permed again, as had Gary Leeds of The Walker Brothers. It was the thing to do, because Hendrix was just becoming big. There was no pecking order. Everybody just sat down where the gear was set up, at Paul’s feet. Keith Richards sat next to Ringo, then everybody else tried to sit next to John, as he was the vocalist, and likely to get the best shots. I think Mick was a bit embarrassed because The Rolling Stones were trying to do His Satanic Majesty’s Request at the same time, and here he was, seemingly at the beck and call of The Beatles.

Tony Bramwell – From “The Beatles: Off the Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

Members of the Small Faces and the design collective the Fool were also among the studio audience. Balloons, flowers, streamers, and “Love” graffiti added to the festive atmosphere. The Beatles and their entourage were dressed in psychedelic clothing and scarves.

The Beatles played the entire song, overdubbing onto the pre-recorded rhythm track, accompanied by the orchestra and their guests. The vocals by John Lennon, bass guitar by Paul McCartney and guitar solo by George Harrison, were played live. The drums by Ringo Starr were not, due to technical reasons. At the last minute, George Martin decided that the 13-piece orchestra would be miming without players knowing about that. To minimize on-air errors, the event was carefully planned, although it was executed to appear spontaneous.

Only Ringo was completely safe, for technical reasons: if the drums were played live, there would be too much leakage onto the microphones that were going to be picking up the sound of the orchestra. Ringo nodded his head solemnly when I explained that to him. I couldn’t tell whether he was relieved at being absolved of the responsibility of playing live, or whether he felt left out.

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

‘I’ve decided to go with yesterday’s orchestral take,’ said George [Martin], ‘I hope you don’t mind, but it’ll make things much easier, and everyone likes the take anyway. They want to keep it.’

‘So…’ I said, ‘the orchestra will be miming, out there, during the live broadcast?’

‘Well, it’s best not to tell them. Then they’ll play away, and it’ll look realistic, but we won’t use the live orchestral sound, we’ll use the already-recorded one.’

Mike Vickers – From “A Week in the Life: working with the Beatles on ‘All You Need Is Love’“, 2019

From start to finish, the entire segment was just over four minutes long, but it felt like hours. It was harrowing, to be sure, but by some miracle there were no technical problems at our end. For a few seconds during the live broadcast, the BBC did in fact lose video signal, but fortunately it was regained quickly, and in any event it wasn’t our fault. The Beatles themselves gave an inspiring performance, though you could see the look of relief on all their faces as they got to the fadeout and realized that they’d actually pulled it off. John came through like a trouper, delivering an amazing vocal despite his nervousness and the plug of chewing gum in his mouth that he forgot to remove just before we went on air. Paul’s playing, as always, was solid, with no gaffes, and even George Harrison’s solo was reasonably good, though he did hit a clunker at the end. Unsurprisingly, despite the complicated score and tricky time changes, the orchestral players came through like the pros they were, with no fluffs whatsoever, even on the most demanding brass riffs.

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

When the ‘live’ button was pressed, I did my best to liven things up a little by throwing streamers, pulling faces behind the cameras and holding cue cards with ‘Smile’ and ‘Laf now’ written on them. I was most impressed to see one of my relatives, Anne Danher, immediately grasped the idea and scrawled, in lipstick, a message to our Aunt in Australia, ‘Come home, Milli, all is forgiven.’ I made sure they got that on camera.

Mike McGear – Paul McCartney’s brother – From “The Beatles: Off the Record” by Keith Badman, 2008

When the Beatles performed on the BBC’s Our World, which transmitted literally around the globe on June 25, 1967, Ruth made a big sign on a piece of cardboard which said “COME BACK MILLY.” The BBC estimated that the broadcast reached 400 million people. That was quite something in those days. You can see it to this day on YouTube in the beginning of the video clip.

Paul and Mike’s Aunt Milly had just departed for Australia to visit her son Jim Kendall and family in Adelaide. She was badly missed by us all.

Mike took the sign to the studios and held it up to the cameras. Believe it or not, Milly told us she had not long arrived and was tired and exhausted from her journey, but they had the telly on in the next room, and were sort of half-watching the screen, when suddenly this placard came up. They were all flabbergasted, as at that stage we were not as tech saturated as now, but it was a real link between our two hemispheres.

I guess you could say it was the first email.

Angie McCartney – Step-mother of Paul McCartney – From “Angie McCartney: My Long and Winding Road“, 2013

After the broadcast ended and the guests had left, John re-recorded some of his vocal parts and Ringo added a snare drum roll to the opening of the song. Those overdubs were added onto Take 59.

In the end, all we had to do was add the effect and duck the last bad note. Paul’s bass playing was fine—there was no need to fix anything—and John’s vocal needed only two lines dropped in in the second verse, where, sure enough, he flubbed a lyric. The only other remaining task was to redo the snare drum roll that Ringo played in the song’s introduction; it had been a last-minute decision for him to do it live during the broadcast, and George Martin felt it could be done a bit better. In this day and age when recordings of live gigs are often tweaked up in the studio afterward to the point where hardly any of the actual performance remains, it might seem unbelievable, but it’s the truth: the only things that were replaced on “All You Need Is Love” for the record release were the snare roll at the beginning, and two lines of the lead vocal.

Geoff Emerick – From “Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles“, 2006

The session ended at 1 am the following morning.

“All You Need Is Love” was mixed the day after, June 26, 1967. The single was rush-released on July 7, with “Baby, You’re A Rich Man” as the B-side.

We were big enough to command an audience of that size, and it was for love. It was for love and bloody peace. It was a fabulous time. I even get excited now when I realise that’s what it was for. Peace and love, people putting flowers in guns.

Ringo Starr – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

For the first time ever, linking five continents and bringing man face to face with mankind, in places as far apart as Canberra and Cape Kennedy, Moscow and Montreal, Samarkand and Söderfors, Takamatsu and Tunis.

BBC publicity

I stayed up all night before the show, drawing on the shirt that I wore. I had some chemicals called Trichem – you could draw on a shirt with them, and then you could launder the shirt and the pattern stayed on. I used them a lot, many’s the shirt or door I’ve painted with them. It was good fun. That shirt got nicked after the show, still – easy come, easy go.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

It was a professional shoot. I remember camera crews and a lot of colourful people. It was psychedelic and all the rest of it, but the BBC filmed it in black and white! If we’d have known that, we’d have filmed it ourselves.

Neil Aspinall – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

I’ve never had a moment’s worry that they wouldn’t come up with something marvelous. The commitment for the TV program was arranged some months ago. The time got nearer and nearer, and they still hadn’t written anything. Then, about three weeks before the program, they sat down to write. The record was completed in ten days. This is an inspired song, because they wrote it for a worldwide program and they really wanted to give the world a message. It could hardly have been a better message. It is a wonderful, beautiful, spine-chilling record.

Brian Epstein, 1967 – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

I read that ‘All You Need Is Love’ was performed before a TV audience of over 400 million in 24 countries. Would you say that was a special record to you?

Oh year… it’s a bit like a Live Aid thing… I think this was the very first time they’d actually hooked up all the television networks all over the world. We had this song ‘All You Need Is Love’ and we thought that’d be the perfect one to use… He [the director] gave us quite a free hand, so we invited all our friends round to the studio. We thought, well if it’s the people of the world meeting the people of the world, we might as well have a great big crowd there and just show ’em what our … crowd is like at the moment… They were all very nice people – probably looked a bit weird to some people, ’cause all the fashions were a bit weird.

We had the orchestra there and we’d rehearsed it a couple of days before… eventually it came to it. They cued from another country – ‘from America to London, England’ – the music started and we started singing this thing. We got through it: I’m surprised nobody panicked. It was a fabulous thing… it’s rare when the world gets together over something like that. I think the majority of people do care: they’re great when they’re asked to give… I think everyone would like to see it more. [There’s] this feeling that people do have, like in things like hospital visiting. I think people are great: they do look after each other… all the nurses looking after the patients now and stuff.

Paul McCartney – Interview with Club Sandwich, 1985

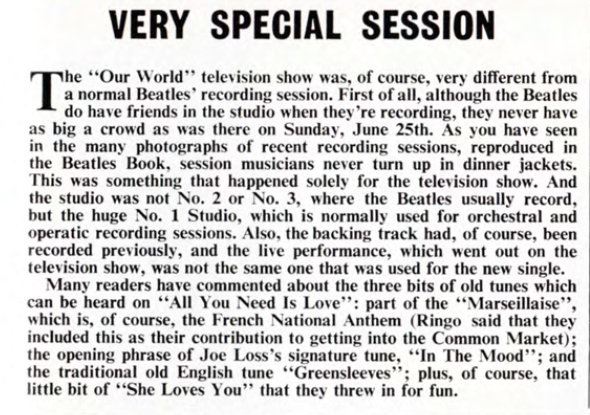

VERY SPECIAL SESSION

The “Our World” television show was, of course, very different from a normal Beatles’ recording session. First of all, although the Beatles do have friends in the studio when they’re recording, they never have as big a crowd as was there on Sunday, June 25th. As you have seen in the many photographs of recent recording sessions, reproduced in the Beatles Book, session musicians never turn up in dinner jackets. This something that happened solely for the television show. And the studio was not No. 2 or No. 3, where the Beatles usually record, but the huge No. 1 Studio, which is normally used for orchestral and operatic recording sessions. Also, the backing track had, of course, been recorded previously, and the live performance, which went out on the television show, was not the same one that was used for the new single.

Many readers have commented about the three bits of old tunes which can be heard on “All You Need Is Love”: part of the “Marseillaise”, which is, of course, the French National Anthem (Ringo said that they included this as their contribution to getting into the Common Market); the opening phrase of Joe Loss’s signature tune, “In The Mood”; and the traditional old English tune “Greensleeves”; plus, of course, that little bit of “She Loves You” that they threw in for fun.

From The Beatles Monthly Book, August 1967

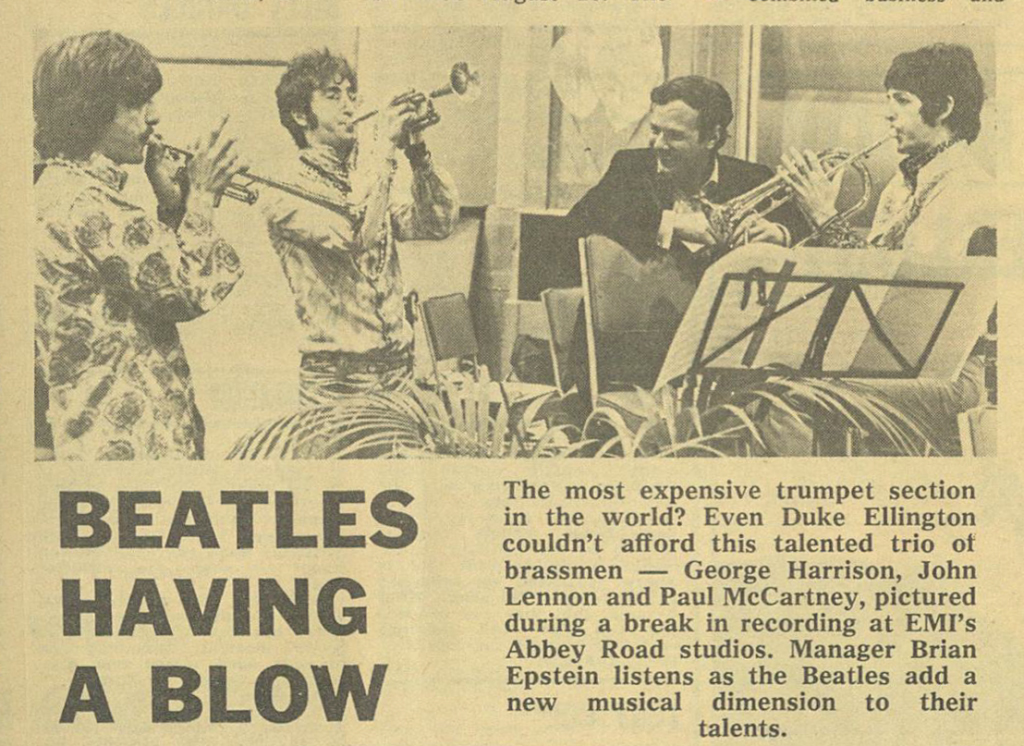

BEATLES HAVING A BLOW

The most expensive trumpet section in the world? Even Duke Ellington couldn’t afford this talented trio of brassmen — George Harrison, John Lennon and Paul McCartney, pictured during a break in recording at EMI’s Abbey Road studios. Manager Brian Epstein listens as the Beatles add a new musical dimension to their talents.

From Melody Maker – July 8, 1967

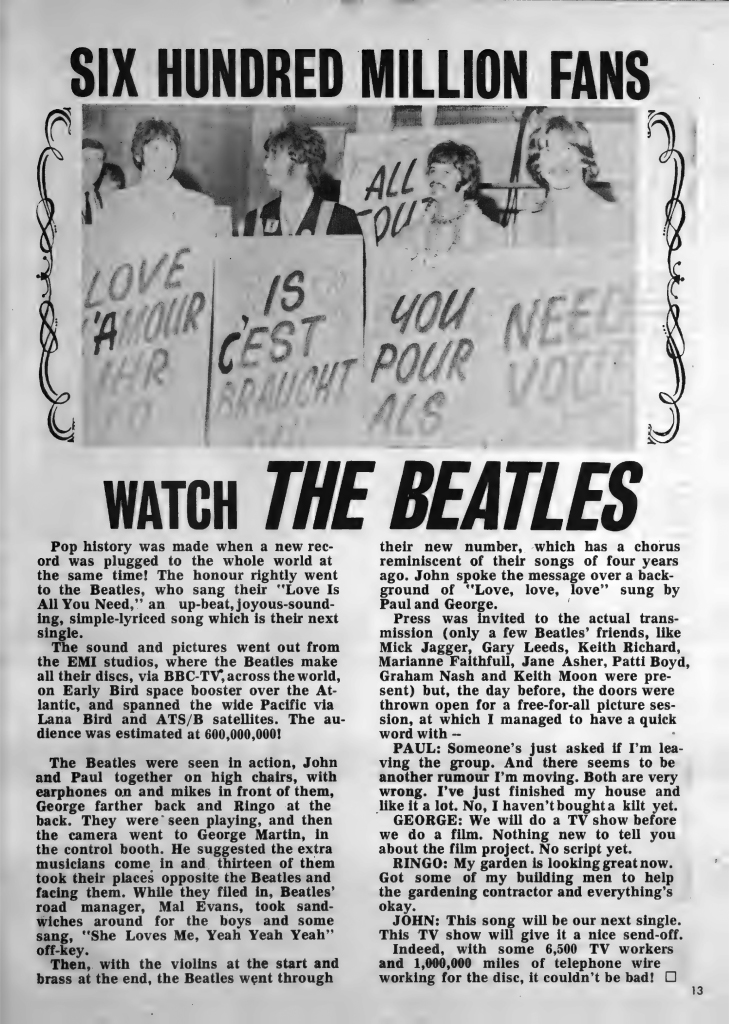

SIX HUNDRED MILLION FANS WATCH THE BEATLES

Pop history was made when a new record was plugged to the whole world at the same time! The honour rightly went to the Beatles, who sang their “Love Is All You Need,” an upbeat, joyous-sounding, simple-lyriced song which is their next single.

The sound and pictures went out from the EMI studios, where the Beatles make all their discs, via BBC-TV, across the world, on Early Bird space booster over the Atlantic, and spanned the wide Pacific via Lana Bird and ATS/B satellites. The audience was estimated at 600,000,000!

The Beatles were seen in action, John and Paul together on high chairs, with earphones on and mikes in front of them, George farther back and Ringo at the back. They were seen playing, and then the camera went to George Martin, in the control booth. He suggested the extra musicians come in and thirteen of them took their place opposite the Beatles and facing them. While they filed in, Beatles’ road manager, Mal Evans, took sandwiches around for the boys and some sang, “She Loves Me, Yeah Yeah Yeah” off-key.

Then, with the violins at the start and brass at the end, the Beatles went through their new number, which has a chorus reminiscent of their songs of four years ago. John spoke the message over a background of “Love, love, love” sung by Paul and George.

Press was invited to the actual transmission (only a few Beatles’ friends, like Mick Jagger, Gary Leeds, Keith Richard, Marianne Faithfull, Jane Asher, Patti Boyd, Graham Nash and Keith Moon were present) but, the day before, the doors were thrown open for a free-for-all picture session, at which I managed to have a quick word with —

PAUL: Someone’s just asked if I’m leaving the group. And there seems to be another rumour I’m moving. Both are very wrong. I’ve just finished my house and like it a lot. No, I haven’t bought a kilt yet.

GEORGE: We will do a TV show before we do a film. Nothing new to tell you about the film project. No script yet.

RINGO: My garden is looking great now. Got some of my building men to help the gardening contractor and everything’s okay.

JOHN: This song will be our next single. This TV show will give it a nice send-off.

Indeed, with some 6,500 TV workers and 1,000,000 miles of telephone wire working for the disc, it couldn’t be bad!

From Hit Parader – November 1967

About “Our World“, from Wikipedia:

Our World was the first live multinational multi-satellite television production. National broadcasters from fourteen countries around the world, coordinated by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), participated in the program. The two-hour event, which was broadcast on Sunday 25 June 1967[a] in twenty-four countries, had an estimated audience of 400 to 700 million people, the largest television audience up to that date. Four communications satellites were used to provide a worldwide coverage, which was a technological milestone in television broadcasting.

Creative artists, including opera singer Heather Harper, film director Franco Zefferelli, conductor Leonard Bernstein, sculptor Alexander Calder and painter Joan Miró were invited to perform or appear in separate live segments, each of them produced by one of the participant broadcasters. The most famous segment is one from the United Kingdom starring the Beatles performing their song “All You Need Is Love” for the first time.

Planning

The project was conceived by British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) producer Aubrey Singer. Due to the magnitude of the production, its coordination was transferred to the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), with Singer as the project’s head. Two communications satellites in geosynchronous orbit over the Atlantic Ocean – Intelsat I (known as “Early Bird”) and Intelsat II F-3 (“Canary Bird”) –, two over the Pacific Ocean – Intelsat II F-2 (“Lani Bird”) and NASA’s ATS-1 – and nine ground stations,[b] in addition to EBU’s Eurovision point-to-point communications network, all monitored by technical and production teams in forty-three control rooms, were used to link North America, Europe, Tunisia, Japan and Australia in real time.

The master control room for the broadcast was the TC1 studio control room at the BBC Television Centre in London. Contributions from continental Europe and Tunisia were routed to London by the EBU Centre in Brussels and contributions from North America, Japan and Australia were routed to London by the – rented – CBS Switching Center in New York. These centers were also in charge of distributing the live master feed from London to the broadcasters in their assigned area. To illustrate the introductory segments, a large set was built at BBC’s TC1 studio, which was operated by the TC2 studio control room. To solve language issues, each receiving broadcaster had its own narrator – such as Cliff Michelmore in the BBC or James Dibble in the ABC – reading in its own language the script written by Antony Jay. Since the contributions from the participating broadcasters were in their native language, a team of interpreters located at BBC’s TC2 studio provided simultaneous translation into English, French and German to the receiving broadcasters, where local commentators voiced-over in their own language the original sound from other broadcasters when in other language.

It took ten months and ten thousand technicians, producers and performers to bring everything together. The ground rules included that no politicians or heads of state could participate in the broadcast. In addition, everything had to be “live”, so no use of videotape or film was permitted, all participants had to have full knowledge of what was going to be included and the sole reason for including an item would be program balance, not geographical or political concerns.

In the dress rehearsal conducted the day before broadcast, the head of the production noticed that, in violation of one of the ground rules, the Mexican broadcaster had pre-recorded their main segment – which included singers, dancers and a flock of white doves taking off right on cue – and attempted to pass it off as live. As getting it together again for the actual broadcast was impossible, it was decided to show them – live – watching their taped performance on monitors.

Participants

Fourteen national broadcasters participated in the program, which was transmitted live to twenty-four countries, with an estimated audience between 400 and 700 million people. Eighteen national broadcasters were about to participate, but those of the Eastern Bloc countries – Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland and the Soviet Union –,[c] pulled out four days before the broadcast in protest of the Western nations’ response to the Six-Day War. Due to this withdrawal, a contribution was requested to the Danish broadcaster, which was not originally a participant. […]

Broadcast

Each broadcaster had an explanatory pre-transmission introduction from their studios to their viewers – such as the introduction by Cliff Michelmore at BBC’s TC5 studio in London for BBC1, the one by James Dibble at ABC’s studio 23 in Sydney for ABC-TV and the interview to philosopher Marshall McLuhan at the television control room in Toronto for CBC Television – just before connecting to the live master feed from London at 7:00 p.m. GMT.

The program was divided into six sections: the Opening, This Moment’s World, The Crowded World, Aspiration to Physical Excellence, Aspiration to Artistic Excellence and The World Beyond. These sections were divided into live segments provided by the participating broadcasters. Just before The Crowded World section, another section was scheduled – The Hungry World –, but due to the withdrawal of the Eastern Bloc countries’ segments, that section was eventually removed and its remaining segments were incorporated into The Crowded World section.

Opening

The opening credits were accompanied by the “Our World theme” played by the Vienna Philharmonic and sung in seventeen different languages by the Vienna Boys’ Choir.

The program began with an introduction from the BBC’s TC1 studio in London and went on attending the births of four children in the delivery rooms at Hokkaido University Hospital in Sapporo, Japan, at Aarhus University Hospital in Aarhus, Denmark, at Hospital de Obstetricia III in Mexico City, Mexico – reported by Pedro Ferriz – and at Charles Camsell Hospital in Edmonton, Canada – reported by Libbie Christensen.

This Moment’s World

Back in BBC’s TC1 studio in London, a journey around the world was introduced starting at the United Austrian Iron and Steelworks in Linz, Austria, and continuing aboard a Protection Civile helicopter flying over the returning weekend traffic at Porte de la Chapelle in Paris, France – reported by Joseph Pasteur –, at the Medina in Tunis, Tunisia and aboard some fishing vessels sailing in the Gulf of Cádiz, Spain, showing the work of the fishermen and praising the country’s fishing industry.

At 7:17 p.m. GMT, the show switched to Glassboro, New Jersey, in the United States – at 3:17 p.m. EDT –, where a summit conference between American president Lyndon Johnson and Soviet premier Alexei Kosygin was taking place – reported by Dick McCutcheon, who ended up talking about the impact of the new television technology on a global scale; and since no politician should be shown, only the exterior of the house where the conference was being held was televised –.[n] At 7:18 p.m. GMT it switched back to Canada, to Two Rivers Ranch in Ghost Lake, Alberta, showing a rancher, and his cutting horse, cutting out a herd of cattle – reported by Bob Switzer –, and at 7:19 p.m. GMT to Kitsilano Beach, in Vancouver’s Point Grey – at 12:19 p.m. PDT –.

At 7:20 p.m. GMT, the program shifted continents to Asia, with Tokyo, Japan – at 4:20 a.m. JST next day – being the next segment showing the construction of the Tokyo subway system.[f] The equator was crossed for the first time in the program when it switched to Australia – at 5:22 a.m. AEST –. This was the most technically complicated point in the broadcast, as both Japanese and Australian satellite ground stations had to reverse their actions: Kashima Ground Station in Japan had to go from transmit mode to receive mode, while Cooby Creek Tracking Station in Australia had to switch from receive to transmit mode. The segment from Melbourne dealt with trams leaving the South Melbourne tram depot – reported by Brian King explaining that sunrise was many hours away as it was winter there –.[o]

The Crowded World

Back in BBC’s TC1 studio in London, a section about human overpopulation was introduced starting at the Controlled Environment Research Laboratory (CERES), the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO)’s phytotron in Canberra, Australia, featuring plant physiologist Lloyd Evans who was carrying out experiments to extend the frequency of cereal crop cycles – reported by Eric Hunter –[o] and continuing at New York City,[n] at Ikushima shrimp farm in Takamatsu, Japan,[f] at a farm in Wisconsin, United States,[n] at Habitat 67 housing complex in the International and Universal Exposition in Montreal, Canada[i] and finishing at Cumbernauld, Scotland – reported by Magnus Magnusson –.[p]

Aspiration to Physical Excellence

Back in BBC’s TC1 studio in London, a section about men and women trying to achieve their best was introduced starting at Empire Pool in Vancouver, Canada, featuring swimmer Elaine Tanner trying to break the 110-yard butterfly World Record – reported by Ted Reynolds –,[i] and continuing at the Equestrian Circle in Castellazzo di Bollate, Italy, featuring riders Piero D’Inzeo and Raimondo D’Inzeo – reported by Alberto Giubilo –,[q] at Söderfors, Sweden, featuring canoeists Gert Fredriksson, Gunnar Utterberg, Lars Andersson and Rolf Pettersson[r] and finishing at Calanque de Callelongue in Marseille, France aboard the maiden voyage of the Téléscaphe, the very first underwater cable car.[k]

Aspiration to Artistic Excellence

Back in BBC’s TC1 studio in London, a section about men and women in pursuit of art was introduced starting at San Pietro church in Tuscania, Italy for the rehearsals of the film Romeo and Juliet, featuring film director Franco Zeffirelli and actors Milo O’Shea, Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey[q] and continuing at Bayreuth Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, West Germany, for the Bayreuth Festival rehearsals of the opera Lohengrin featuring director Wolfgang Wagner, conductor Rudolf Kempe and singers Heather Harper and Grace Hoffman,[s] at Fondation Maeght in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France featuring sculptor Alexander Calder and painter Joan Miró,[k] at Mexico City, Mexico featuring singers Antonio Aguilar singing “Allá en el Rancho Grande” on horseback and Flor Silvestre singing “Como México no hay dos” – reported by León Michel –,[h] at the Lincoln Center in New York City featuring conductor Leonard Bernstein and pianist Van Cliburn rehearsing Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3,[n] and finishing at EMI Recording Studio 1 in Abbey Road, London, for the first recording session of “All You Need Is Love” by the Beatles – reported by Steve Race –.[p]

The World Beyond

Back in BBC’s TC1 studio in London, a section about outer space was introduced starting at Kennedy Space Center at Cape Kennedy in the United States,[n] continuing at Parkes Observatory in Parkes, Australia, featuring John Gatenby Bolton tracking quasar 0237–23, the most distant known object in the universe at the time – reported by Kim Corcoran –[o] and finishing back in BBC’s TC1 studio in London for a closing segment intercutting live footage from several of the locations already shown.

Legacy – The Beatles’ segment

As the broadcast took place at the height of the Vietnam War, the Beatles were asked to write a song with a positive message. They topped the event with their debut performance of “All You Need Is Love”. They invited many of their friends to the event to create a festive atmosphere and to join in on the song’s chorus. Among the friends were members of the Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton, Marianne Faithfull, Keith Moon and Graham Nash.

Although Our World was originally recorded and transmitted in black-and-white, for its use in the 1995 TV special The Beatles Anthology, the Beatles’ performance on the program was colourised, using colour photographs taken at the event as a reference. The sequence opens in its original monochromatic format and rapidly morphs into full colour, conveying the brightly coloured flower power and psychedelic-style clothing worn by the Beatles and their guests that was popular during what was subsequently dubbed the “Summer of Love”. […]

Recording • Take 48

Recording • Take 49

Recording • Take 50

Recording • BBC Rehearsal Take 1

Recording • BBC Rehearsal Take 2

Recording • BBC Rehearsal Take 3

Recording • Take 51

Recording • Take 52

Recording • Take 53

Recording • Take 54

Recording • Take 55

Recording • Take 56

Recording • Take 57

Recording • Take 58

Recording • Take 59

Recording • SI onto take 59

The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions • Mark Lewisohn

The definitive guide for every Beatles recording sessions from 1962 to 1970.

We owe a lot to Mark Lewisohn for the creation of those session pages, but you really have to buy this book to get all the details - the number of takes for each song, who contributed what, a description of the context and how each session went, various photographies... And an introductory interview with Paul McCartney!

The Beatles Recording Reference Manual: Volume 3: Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band through Magical Mystery Tour (late 1966-1967)

The third book of this critically - acclaimed series, nominated for the 2019 Association for Recorded Sound Collections (ARSC) award for Excellence In Historical Recorded Sound, "The Beatles Recording Reference Manual: Volume 3: Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band through Magical Mystery Tour (late 1966-1967)" captures the band's most innovative era in its entirety. From the first take to the final remix, discover the making of the greatest recordings of all time. Through extensive, fully-documented research, these books fill an important gap left by all other Beatles books published to date and provide a unique view into the recordings of the world's most successful pop music act.

If we modestly consider the Paul McCartney Project to be the premier online resource for all things Paul McCartney, it is undeniable that The Beatles Bible stands as the definitive online site dedicated to the Beatles. While there is some overlap in content between the two sites, they differ significantly in their approach.

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.