Recording studio: EMI Studios, Abbey Road Studios • London • UK

Single Oct 11, 1965 • "Kansas City / Boys" by The Beatles released in the US

Session Oct 12, 1965 • Recording "Run For Your Life", "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)"

Session Oct 12 - Nov 30, 1965 • Recording "Rubber Soul"

Session Oct 13, 1965 • Recording "Drive My Car"

Article Oct 15, 1965 • Paul and Jane attend Ben E. King concert at The Scotch of St James

AlbumSome of the songs worked on during this session were first released on the "Rubber Soul (UK Mono)" LP

1965 was a very busy year for The Beatles. They spent the early months filming their second feature film, “Help!“, and recording the accompanying album. The summer months were taken up with extensive touring across Europe and the United States. In September, they took a six-week break, which they partly used to write new material.

They were committed to a new UK tour starting on December 3, 1965, and to releasing another studio album before the end of the year. They entered the studio on October 12, 1965 to record their new album. “Rubber Soul” was recorded in record time. But despite the time pressure, the album marked a clear shift in direction. The Beatles began moving away from straightforward pop songs towards more mature material with more elaborate lyrics. They also expanded their studio approach, experimenting with new sounds and techniques, including the introduction of the sitar on a pop recording for the first time, and devoting more time and care to the recording of each track.

The same sessions also produced the new single “We Can Work It Out / Day Tripper“, released on December 3, 1965, the same day as the album and the opening night of the UK tour.

From Wikipedia:

Recording history

Rubber Soul was a matter of having all experienced the recording studio, having grown musically as well, but [getting] the knowledge of the place, of the studio. We were more precise about making the album, that’s all, and we took over the cover and everything.

Recording for Rubber Soul began on 12 October 1965 at EMI Studios (now Abbey Road Studios) in London; final production and mix down took place on 15 November. During the sessions, the Beatles typically focused on fine-tuning the musical arrangement for each song, an approach that reflected the growing division between the band as a live act and their ambitions as recording artists. The album was one of the first projects that Martin undertook after leaving EMI’s staff and co-founding Associated Independent Recording (AIR). Martin later described Rubber Soul as “the first album to present a new, growing Beatles to the world”, adding: “For the first time we began to think of albums as art on their own, as complete entities.” It was the final Beatles album that recording engineer Norman Smith worked on before being promoted by EMI to record producer. The sessions were held over thirteen days and totalled 113 hours, with a further seventeen hours (spread over six days) allowed for mixing.

The band were forced to work to a tight deadline to ensure the album was completed in time for a pre-Christmas release. They were nevertheless in the unfamiliar position of being able to dedicate themselves solely to a recording project, free of touring, filming and radio engagements. The Beatles ceded to two interruptions during this time. They received their MBEs at Buckingham Palace on 26 October, from Queen Elizabeth II, and on 1–2 November, the band filmed their segments for The Music of Lennon & McCartney, a Granada Television tribute to the Lennon–McCartney songwriting partnership. According to author Christopher Bray, this intensive recording made Rubber Soul not just unusual in the Beatles’ career but “emphatically unlike those LPs made by other bands”. From 4 November – by which point only around half the required number of songs were near completion – the Beatles’ sessions were routinely booked to finish at 3 am each day.

After A Hard Day’s Night in 1964, Rubber Soul was the second Beatles album to contain only original material. As the band’s main writers, Lennon and McCartney struggled to complete enough songs for the project. After a session on 27 October was cancelled due to a lack of new material, Martin told a reporter that he and the group “hope to resume next week” but would not consider recording songs by any other composers. The Beatles completed “Wait” for the album, having taped its rhythm track during the sessions for Help! in June 1965. They also recorded the instrumental “12-Bar Original“, a twelve-bar blues in the style of Booker T. & the M.G.’s. Credited to Lennon, McCartney, Harrison and Starr, it remained unreleased until 1996.

The group recorded “Day Tripper” and “We Can Work It Out” during the Rubber Soul sessions for release as a single accompanying the album. To avoid having to promote the single with numerous television appearances, the Beatles chose to produce film clips for the two songs, the first time they had done so for a single. Directed by Joe McGrath, the clips were filmed at Twickenham Film Studios in south-west London on 23 November.

Studio aesthetic and sounds

[On Rubber Soul] the Beatles demonstrated an ability to reach beyond the confines of acceptable rock and roll techniques and bring to the studio truly innovative ideas such as layering bass and fuzz-bass guitars, creating rhymes in different languages, mixing modes on a single song, utilizing tape manipulation to give instruments entirely new sounds, and introducing the sitar – a most unusual instrument for a rock band.

Lennon recalled that Rubber Soul was the first album over which the Beatles took control in the studio and made demands rather than accept standard recording practices. According to Riley, the album reflects “a new affection for recording” over live performance. Author Philip Norman similarly writes that, with the Beatles increasingly drawn towards EMI’s large cache of “exotic” musical instruments, combined with their readiness to incorporate “every possible resource of the studio itself” and Martin’s skills as a classical arranger, “Implicitly, from the very start, this [music] was not stuff intended to be played live on stage.”

According to Barry Miles, a leading figure in the UK underground whom Lennon and McCartney befriended at this time, Rubber Soul and its 1966 follow-up, Revolver, were “when [the Beatles] got away from George Martin, and became a creative entity unto themselves”. In 1995, Harrison said that Rubber Soul was his favourite Beatles album, adding: “we certainly knew we were making a good album. We did spend more time on it and tried new things. But the most important thing about it was that we were suddenly hearing sounds that we weren’t able to hear before.”

During the sessions, McCartney played a solid-body Rickenbacker 4001 bass guitar, which produced a fuller sound than his hollow-body Hofner. The Rickenbacker’s design allowed for greater melodic precision, a characteristic that led McCartney to contribute more intricate bass lines. For the rest of his Beatles career, the Rickenbacker would become McCartney’s primary bass for studio work. Harrison used a Fender Stratocaster for the first time, most notably in his lead guitar part on “Nowhere Man“. The variety in guitar tones throughout the album was also aided by Harrison and Lennon’s use of capos, such as in the high-register parts on “If I Needed Someone” and “Girl“.

On Rubber Soul, the Beatles departed from standard rock and roll instrumentation, particularly in Harrison’s use of the Indian sitar on “Norwegian Wood”. Having been introduced to the string instrument on the set of the 1965 film Help!, Harrison’s interest was fuelled by fellow Indian music fans Roger McGuinn and David Crosby of the Byrds, partway through the Beatles’ US tour. Music journalist Paul Du Noyer describes the sitar part as “simply a sign of the whole band’s hunger for new musical colours”, but also “the pivotal moment of Rubber Soul“. The Beatles also made use of harmonium during the sessions, marking that instrument’s introduction into rock music.

The band’s willingness to experiment with sound was further demonstrated in McCartney playing fuzz bass on “Think for Yourself” over his standard bass part, and their employing a piano made to sound like a baroque harpsichord on “In My Life“. The latter effect came about when, in response to Lennon suggesting he play something “like Bach”, Martin recorded the piano solo with the tape running at half-speed; when played back at normal speed, the sped-up sound gave the illusion of a harpsichord. In this way, the Beatles used the recording studio as a musical instrument, an approach that they and Martin developed further with Revolver. In Prendergast’s description, “bright ethnic percussion” was among the other “great sounds” that filled the album.

Lennon, McCartney and Harrison’s three-part harmony singing was another musical detail that came to typify the Rubber Soul sound. According to musicologist Walter Everett, some of the vocal arrangements feature the same “pantonal planing of three-part root-position triads” adopted by the Byrds, who had initially based their harmonies on the style used by the Beatles and other British Invasion bands. Riley says that the Beatles softened their music on Rubber Soul, yet by reverting to slower tempos they “draw attention to how much rhythm can do”. Wide separation in the stereo image ensured that subtleties in the musical arrangements were heard; in Riley’s description, this quality emphasised the “richly textured” arrangements over “everything being stirred together into one high-velocity mass”.

McCartney said that as part of their increased involvement in the album’s production, the band members attended the mixing sessions rather than let Martin work in their absence. Until late in their career, the “primary” version of the Beatles’ albums was always the monophonic mix. According to Beatles historian Bruce Spizer, Martin and the EMI engineers devoted most of their time and attention to the mono mixdowns, and generally regarded stereo as a gimmick. The band were not usually present for the stereo mixing sessions.

Band dynamics

While Martin recalled the sessions as having been “a very joyful time”, Smith felt “something had happened between Help! and Rubber Soul“, and the family atmosphere that had once characterised the relationship between the Beatles and their production team was absent. He said the project revealed the first signs of artistic conflict between Lennon and McCartney, and friction within the band as more effort was spent on perfecting each song. This also manifested in a struggle over which song should be the A-side of their next single, with Lennon insisting on “Day Tripper” (of which he was the primary writer) and publicly contradicting EMI’s announcement about the upcoming release. […]

‘Rubber Soul’ for me is the beginning of my adult life

Paul McCartney – From Facebook, December 3, 2025

In October 1965, we started to record the album. Things were changing. The direction was moving away from the poppy stuff like ‘Thank You Girl’, ‘From Me To You’ and ‘She Loves You’. The early material was directly relating to our fans, saying, ‘Please buy this record,’ but now we’d come to a point where we thought, ‘We’ve done that. Now we can branch out into songs that are more surreal, a little more entertaining.’ And other people were starting to arrive on the scene who were influential. Dylan was influencing us quite heavily at that point.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

We had to write 14 songs for this new LP, plus two for the single. It’s a question of value for money — more than anything else — we want to do what we would have liked when we were record-buyers ourselves. A 14-track LP and a separate single is unheard of in the States — there you’d have 12 tracks, and the single would just be two numbers from the LP. They’re not the same as English record people. It’s not quite that they’re unscrupulous, but they’ll put the singles on the LP just to fill up. It’s cheating anyhow, but the scene is different there. The kids in America can afford to buy an LP just for a few new tracks, but here they’re more choosy.

Paul McCartney – From interview for London Life, December 4, 1965

John and I were writing quite well by 1965. For a while we didn’t really have enough home-made material, but we did start to around the time of Rubber Soul.

Most of the time we wrote together. We’d go and lock ourselves away and say, ‘OK, what have we got?’ John might have half an idea, something like for ‘In My Life’: ‘There are places I remember…’ (I think he had that first as a lyric – like a poem, ‘Places I Remember’) and we’d work out the extra melody needed, and the main theme, and by the end of three or four hours we nearly always had it cracked! I can’t remember coming away from one of those sessions not having finished a song.

One of the stickiest was ‘Drive My Car’, because we couldn’t get past one phrase that we had: ‘You can buy me golden rings’. We struggled for hours; I think we struggled too long. Then we had a break and suddenly it came: ‘Wait a minute: “Drive my car!”’ Then we got into the fun of that scenario: ‘Oh, you can drive my car! What is it? What’s he doing? Is he offering a job as a chauffeur, or what?’ And then it became much more ambiguous, which we liked, instead of golden rings, which was a bit poofy. ‘Golden rings’ became ‘beep beep, yeah’. We both came up with that. Suddenly we were in LA: cars, chauffeurs, open-top Cadillacs, and it was a whole other thing.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

Rubber Soul was the pot album, and Revolver was the acid. It was like pills influenced us in Hamburg, drink influenced us in so and so; I mean, we weren’t all stoned making Rubber Soul, because in those days we couldn’t work on pot. We never recorded under acid.

John Lennon – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

We were getting better, technically and musically. We finally took over the studio. In the early days, we had to take what we were given; we had to make it in two hours, and one or three takes was enough and we didn’t know how you could get more bass – we were learning the techniques. Then we got contemporary. I think Rubber Soul was about when it started happening.

Everything I, any of us, do is influenced, but it began to take its own form. Rubber Soul was a matter of having all experienced the recording studio, having grown musically as well, but [getting] the knowledge of the place, of the studio. We were more precise about making the album, that’s all, and we took over the cover and everything.

John Lennon – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

Rubber Soul was my favourite album, even at that time. I think that it was the best one we made; we certainly knew we were making a good album. We did spend a bit more time on it and tried new things. But the most important thing about it was that we were suddenly hearing sounds that we weren’t able to hear before. Also, we were being more influenced by other people’s music and everything was blossoming at that time; including us, because we were still growing.

George Harrison – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

Songwriting for me, at the time of Rubber Soul, was a bit frightening because John and Paul had been writing since they were three years old. It was hard to come in suddenly and write songs. They’d had a lot of practice. They’d written most of their bad songs before we’d even got into the recording studio. I had to come from nowhere and start writing, and have something with at least enough quality to put on the record alongside all the wondrous hits. It was very hard.

George Harrison – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

By the time of Rubber Soul they were ready for new musical directions. In the early days they were very influenced by American rhythm-and-blues. I think that the so-called ‘Beatles sound’ had something to do with Liverpool being a port. Maybe they heard the records before we did. They certainly knew much more about Motown and black music than anybody else did, and that was a tremendous influence on them. And then, as time went on, other influences became apparent: classical influences and modern music. That was from 1965 and beyond.

George Martin – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

The Beatles were always looking for new sounds, always looking to a new horizon and it was a continual but happy strain to try and provide new things for them. They were always wanting to try new instruments even when they didn’t know much about them.

George Martin – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

They had a great time in the studio and, in the main, they were enormously happy times. They would fool around a lot and have a laugh, particularly when overdubbing voices. John was funny; they all were. My memory is of a very joyful time.

George Martin – From “The Beatles Anthology” book, 2000

“I think Rubber Soul was the first of The Beatles’ albums which presented a new Beatles to the world,” reckons George Martin, who was close enough to the proceedings to know. “Up till then, we had been making albums rather like a collection of singles. Now we were really beginning to think about albums as a bit of art on their own. And Rubber Soul was the first to emerge that way.”

Miles, Barry. The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years (Kindle Locations 5683-5687). Music Sales. Kindle Edition.

John Lennon concurred: “We were just getting better, technically and musically, that’s all. We finally took over the studio. On Rubber Soul, we were sort of more precise about making the album, and we took over the cover and everything. It was Paul’s album title, just a pun. There is no great mysterious meaning behind all this, it was just four boys, working out what to call a new album.”

Miles, Barry. The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years (Kindle Locations 5687-5690). Music Sales. Kindle Edition.

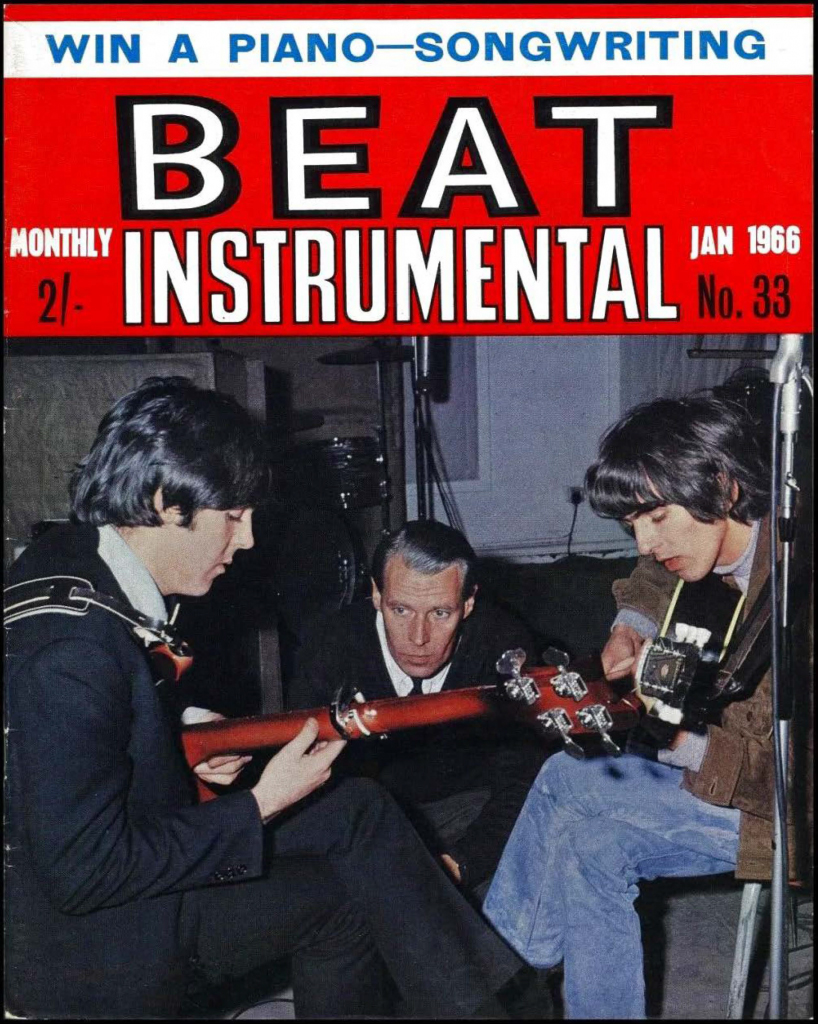

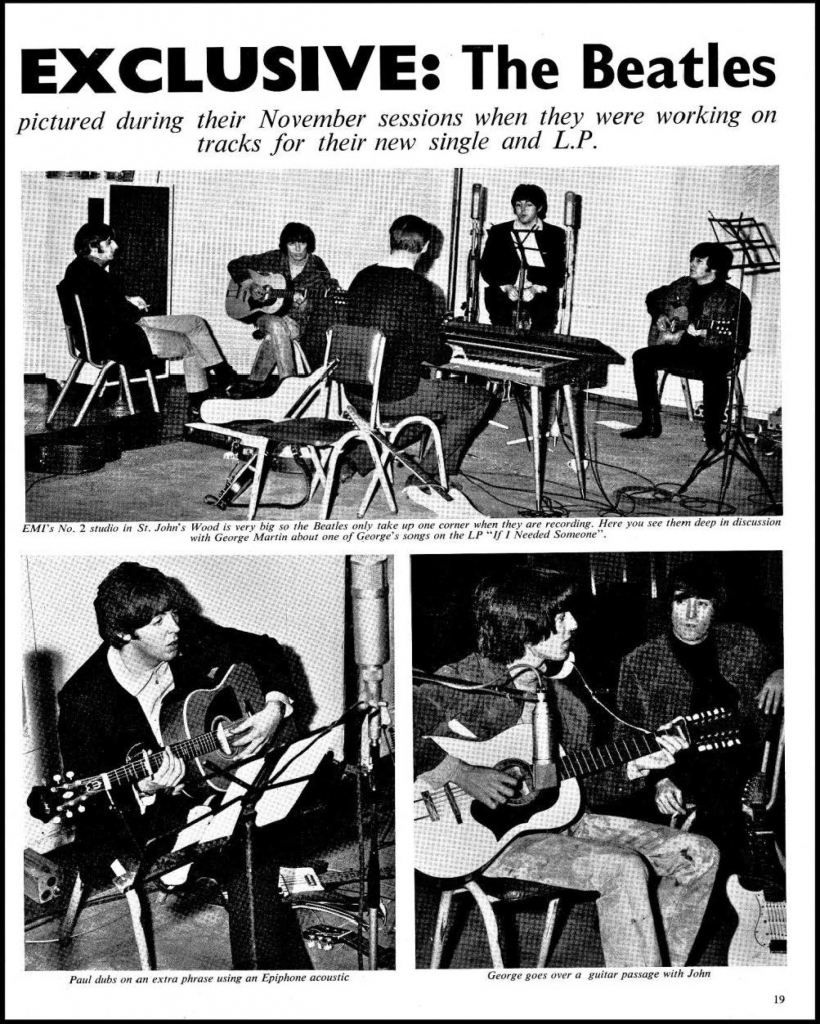

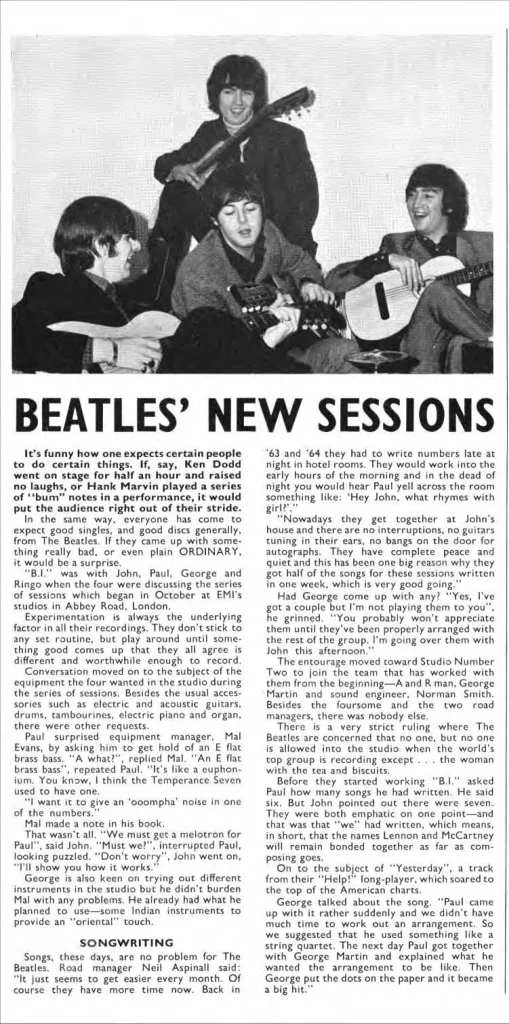

BEATLES’ NEW SESSIONS

It’s funny how one expects certain people to do certain things. If, say, Ken Dodd went on stage for half an hour and raised no laughs, or Hank Marvin played a series of “bum” notes in a performance, it would put the audience right out of their stride.

In the same way, everyone has come to expect good singles, and good discs generally, from The Beatles. If they came up with something really bad, or even plain ORDINARY, it would be a surprise.

“B.I.” was with John, Paul, George and Ringo when the four were discussing the series of sessions which began in October at EMI’s studios in Abbey Road, London.

Experimentation is always the underlying factor in all their recordings. They don’t stick to any set routine, but play around until something good comes up that they all agree is different and worthwhile enough to record.

Conversation moved on to the subject of the equipment the four wanted in the studio during the series of sessions. Besides the usual accessories such as electric and acoustic guitars, drums, tambourines, electric piano and organ, there were other requests.

Paul surprised equipment manager, Mal Evans, by asking him to get hold of an E flat brass bass. “A what?” replied Mal. “An E flat brass bass,” repeated Paul. “It’s like a euphonium. You know, I think the Temperance Seven used to have one. I want it to give an ‘oompha’ noise in one of the numbers.”

Mal made a note in his book.

That wasn’t all. “We must get a melotron for Paul” said John. “Must we?” interrupted Paul, looking puzzled. “Don’t worry,” John went on, “I’ll show you how it works.”

George is also keen on trying out different instruments in the studio but he didn’t burden Mal with any problems. He already had what he planned to use — some Indian instruments to provide an “oriental” touch.

Songs, these days, are no problem for The Beatles. Road manager Neil Aspinall said: “It just seems to get easier every month. Of course they have more time now. Back in ’63 and ’64 they had to write numbers late at night in hotel rooms. They would work into the early hours of the morning and in the dead of night you would hear Paul yell across the room something like: “Hey John, what rhymes with girl?”

“Nowadays they get together at John’s house and there are no interruptions, no guitars tuning in their ears, no bangs on the door for autographs. They have complete peace and quiet and this has been one big reason why they got half of the songs for these sessions written in one week, which is very good going.”

Had George come up with any? “Yes, I’ve got a couple but I’m not playing them to you,” he grinned. “You probably won’t appreciate them until they’ve been properly arranged with the rest of the group. I’m going over them with John this afternoon.”

The entourage moved toward Studio Number Two to join the team that has worked with them from the beginning — A and R man, George Martin and sound engineer, Norman Smith. Besides the foursome and the two road managers, there was nobody else.

There is a very strict ruling where The Beatles are concerned that no one, but no one is allowed into the studio when the world’s top group is recording except… the woman with the tea and biscuits.

Before they started working “B.I.” asked Paul how many songs he had written. He said six. But John pointed out there were seven. They were both emphatic on one point—and that was that “we” had written, which means, in short, that the names Lennon and McCartney will remain bonded together as far as composing goes.

On to the subject of “Yesterday”, a track from their “Help!” long-player, which soared to the top of the American charts.

George talked about the song. “Paul came up with it rather suddenly and we didn’t have much time to work out an arrangement. So we suggested that he used something like a string quartet. The next day Paul got together with George Martin and explained what he wanted the arrangement to be like. Then George put the dots on the paper and it became a big hit.”

From Beat Instrumental – January 1966

Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)

Oct 12, 1965 • Recording "Run For Your Life", "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)"

Oct 12, 1965 • Recording "Run For Your Life", "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)"

Oct 13, 1965 • Recording "Drive My Car"

Oct 16, 1965 • Recording "Day Tripper", "If I Needed Someone"

Oct 16, 1965 • Recording "Day Tripper", "If I Needed Someone"

Oct 18, 1965 • Recording "If I Needed Someone", "In My Life"

Oct 18, 1965 • Recording "If I Needed Someone", "In My Life"

Oct 20, 1965 • Recording "We Can Work It Out"

Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)

Oct 21, 1965 • Recording "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)", "Nowhere Man"

Oct 21, 1965 • Recording "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)", "Nowhere Man"

Oct 22, 1965 • Recording "In My Life", "Nowhere Man"

Oct 22, 1965 • Recording "In My Life", "Nowhere Man"

Oct 24, 1965 • Recording “I’m Looking Through You”

Oct 25, 1965 • Mixing "Drive My Car", "In My Life", "If I Needed Someone", "Day Tripper", "Norwegian Wood", "Nowhere Man"

Oct 25, 1965 • Mixing "Drive My Car", "In My Life", "If I Needed Someone", "Day Tripper", "Norwegian Wood", "Nowhere Man"

Oct 25, 1965 • Mixing "Drive My Car", "In My Life", "If I Needed Someone", "Day Tripper", "Norwegian Wood", "Nowhere Man"

Oct 25, 1965 • Mixing "Drive My Car", "In My Life", "If I Needed Someone", "Day Tripper", "Norwegian Wood", "Nowhere Man"

Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)

Oct 25, 1965 • Mixing "Drive My Car", "In My Life", "If I Needed Someone", "Day Tripper", "Norwegian Wood", "Nowhere Man"

Oct 25, 1965 • Mixing "Drive My Car", "In My Life", "If I Needed Someone", "Day Tripper", "Norwegian Wood", "Nowhere Man"

Oct 26, 1965 • Mixing "Drive My Car", "Day Tripper", "In My Life", "If I Needed Someone", "Norwegian Wood", "Nowhere Man"

Oct 26, 1965 • Mixing "Drive My Car", "Day Tripper", "In My Life", "If I Needed Someone", "Norwegian Wood", "Nowhere Man"

Oct 26, 1965 • Mixing "Drive My Car", "Day Tripper", "In My Life", "If I Needed Someone", "Norwegian Wood", "Nowhere Man"

Oct 26, 1965 • Mixing "Drive My Car", "Day Tripper", "In My Life", "If I Needed Someone", "Norwegian Wood", "Nowhere Man"

Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)

Oct 26, 1965 • Mixing "Drive My Car", "Day Tripper", "In My Life", "If I Needed Someone", "Norwegian Wood", "Nowhere Man"

Oct 26, 1965 • Mixing "Drive My Car", "Day Tripper", "In My Life", "If I Needed Someone", "Norwegian Wood", "Nowhere Man"

Oct 28, 1965 • Mixing "We Can Work It Out"

Oct 29, 1965 • Recording and mixing "We Can Work It Out", mixing "Day Tripper"

Oct 29, 1965 • Recording and mixing "We Can Work It Out", mixing "Day Tripper"

Nov 03, 1965 • Recording "Michelle"

Nov 04, 1965 • Recording "What Goes On", "12-Bar Original"

Nov 04, 1965 • Recording "What Goes On", "12-Bar Original"

Nov 06, 1965 • Recording “I’m Looking Through You“

Beatle Speech

Nov 08, 1965 • Recording "Think For Yourself", "The Beatles Third Christmas Record"

The Beatles' Third Christmas Record

Nov 08, 1965 • Recording "Think For Yourself", "The Beatles Third Christmas Record"

Nov 08, 1965 • Recording "Think For Yourself", "The Beatles Third Christmas Record"

Nov 09, 1965 • Mixing "Michelle", "What Goes On", "Run For Your Life", "Think For Yourself", "The Beatles Third Christmas Record"

Nov 09, 1965 • Mixing "Michelle", "What Goes On", "Run For Your Life", "Think For Yourself", "The Beatles Third Christmas Record"

The Beatles' Third Christmas Record

Nov 09, 1965 • Mixing "Michelle", "What Goes On", "Run For Your Life", "Think For Yourself", "The Beatles Third Christmas Record"

Nov 09, 1965 • Mixing "Michelle", "What Goes On", "Run For Your Life", "Think For Yourself", "The Beatles Third Christmas Record"

Nov 09, 1965 • Mixing "Michelle", "What Goes On", "Run For Your Life", "Think For Yourself", "The Beatles Third Christmas Record"

Nov 10, 1965 • Mixing "Run For Your Life", "We Can Work It Out", recording "The Word", "I'm Looking Through You"

Nov 10, 1965 • Mixing "Run For Your Life", "We Can Work It Out", recording "The Word", "I'm Looking Through You"

Nov 10, 1965 • Mixing "Run For Your Life", "We Can Work It Out", recording "The Word", "I'm Looking Through You"

Nov 10, 1965 • Mixing "Run For Your Life", "We Can Work It Out", recording "The Word", "I'm Looking Through You"

Nov 11, 1965 • Mixing "The Word", recording "You Won't See Me", "Girl", "Wait", "I'm Looking Through You"

Nov 11, 1965 • Mixing "The Word", recording "You Won't See Me", "Girl", "Wait", "I'm Looking Through You"

Nov 11, 1965 • Mixing "The Word", recording "You Won't See Me", "Girl", "Wait", "I'm Looking Through You"

Nov 11, 1965 • Mixing "The Word", recording "You Won't See Me", "Girl", "Wait", "I'm Looking Through You"

Nov 11, 1965 • Mixing "The Word", recording "You Won't See Me", "Girl", "Wait", "I'm Looking Through You"

Nov 15, 1965 • Mixing "I'm Looking Through You", "You Won't See Me", "Girl", "Wait", "The Word", "Michelle"

Nov 15, 1965 • Mixing "I'm Looking Through You", "You Won't See Me", "Girl", "Wait", "The Word", "Michelle"

Nov 15, 1965 • Mixing "I'm Looking Through You", "You Won't See Me", "Girl", "Wait", "The Word", "Michelle"

Nov 15, 1965 • Mixing "I'm Looking Through You", "You Won't See Me", "Girl", "Wait", "The Word", "Michelle"

Nov 15, 1965 • Mixing "I'm Looking Through You", "You Won't See Me", "Girl", "Wait", "The Word", "Michelle"

Nov 15, 1965 • Mixing "I'm Looking Through You", "You Won't See Me", "Girl", "Wait", "The Word", "Michelle"

Nov 30, 1965 • Mixing "12-Bar Original"

The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions • Mark Lewisohn

The definitive guide for every Beatles recording sessions from 1962 to 1970. We owe a lot to Mark Lewisohn for the creation of those session pages, but you really have to buy this book to get all the details - the number of takes for each song, who contributed what, a description of the context and how each session went, various photographies... And an introductory interview with Paul McCartney!

The Beatles Recording Reference Manual - Volume 2 - Help! through Revolver (1965-1966)

The second book of the Association for Recorded Sound Collections (ARSC)-nominated series, "The Beatles Recording Reference Manual: Volume 2: Help! through Revolver (1965-1966)" follows the evolution of the band from the end of Beatlemania with "Help!" through the introspection of "Rubber Soul" up to the sonic revolution of "Revolver". From the first take to the final remix, discover the making of the greatest recordings of all time.Through extensive, fully-documented research, these books fill an important gap left by all other Beatles books published to date and provide a unique view into the recordings of the world's most successful pop music act.

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.