April 10 to August 1970

Paul and Linda McCartney go and live in Scotland for a few months

Last updated on December 17, 2023

April 10 to August 1970

Last updated on December 17, 2023

Location: High Park Farm, Kintyre, Scotland

Article Apr 09, 1970 • The "McCartney" press kit is sent to UK press

Interview Apr 09, 1970 • Paul McCartney interview for Apple Records

Article April 10 to August 1970 • Paul and Linda McCartney go and live in Scotland for a few months

Article Apr 10, 1970 • Newspapers announce that Paul McCartney has quit the Beatles

Article Apr 14, 1970 • Paul McCartney writes to Allen Klein about "The Long And Winding Road"

Officially appears on Ram

Officially appears on Ram

Officially appears on 4th of July

Officially appears on Ram

Officially appears on Another Day / Oh Woman Oh Why

Officially appears on Ram

Officially appears on Ram - Archive Collection

Officially appears on Wild Life - Archive Collection

Officially appears on Ram

Officially appears on Ram

Officially appears on Ram

Officially appears on Red Rose Speedway

Officially appears on Mary Had A Little Lamb / Little Woman Love (UK)

Officially appears on Live And Let Die / I Lie Around

Officially appears on The In-Laws (Music From The Motion Picture)

Officially appears on Wild Life

Officially appears on Red Rose Speedway

Officially appears on Flaming Pie

Officially appears on Wild Life

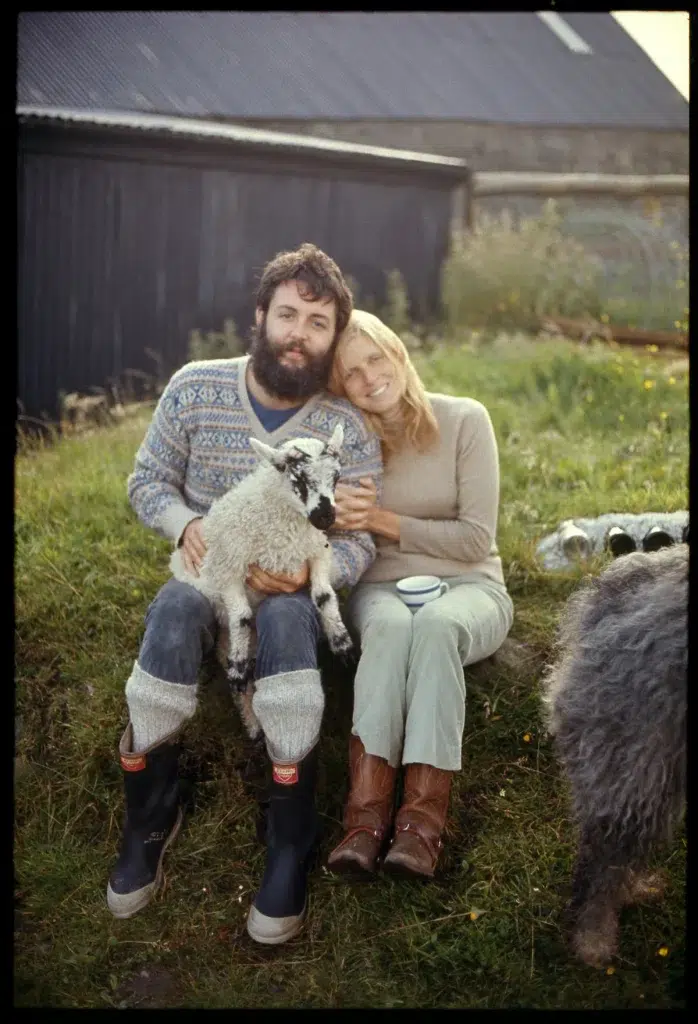

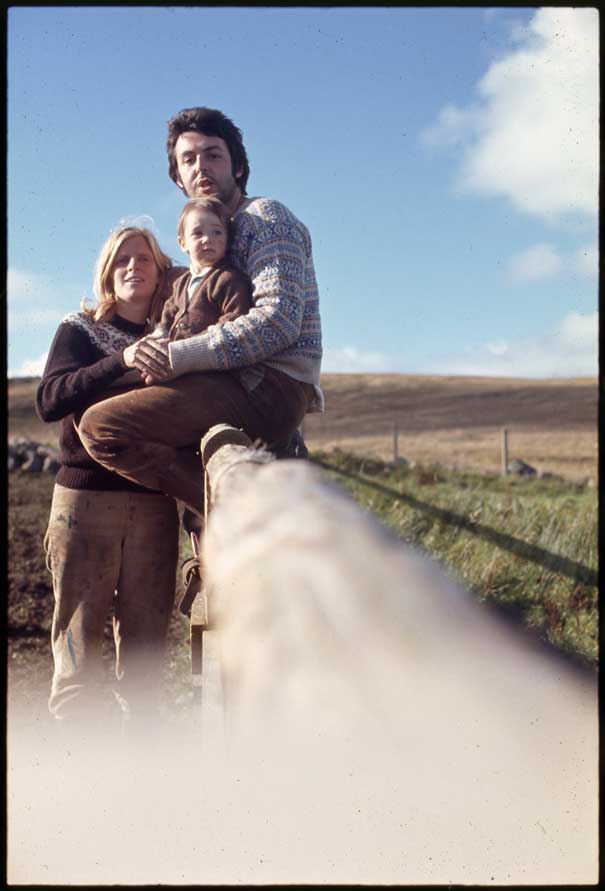

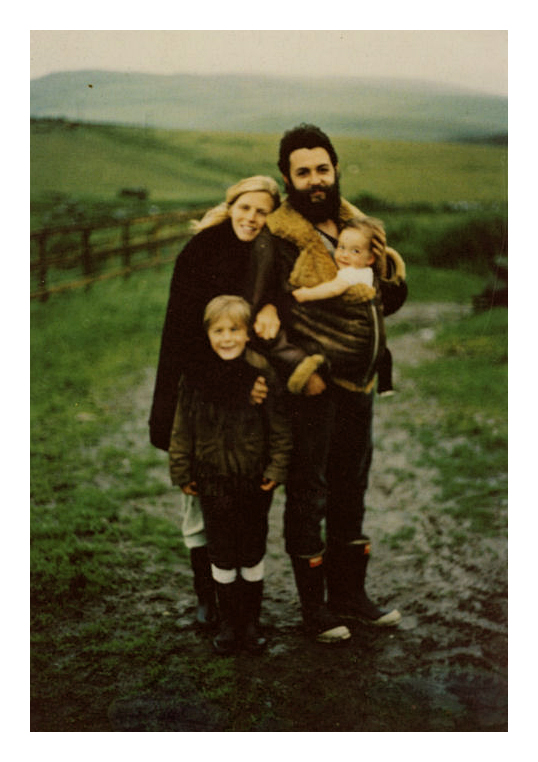

On April 10, 1970, The Daily Mirror announced on its first page, “Paul is quitting The Beatles“. On the same day, Paul McCartney, his wife Linda, and their daughters Heather and Mary, escaped London to live in Scotland. They would stay there till August 1970.

This was a period of depression for Paul, following his public announcement (in the press release of his debut solo album, “McCartney“) that The Beatles were no more.

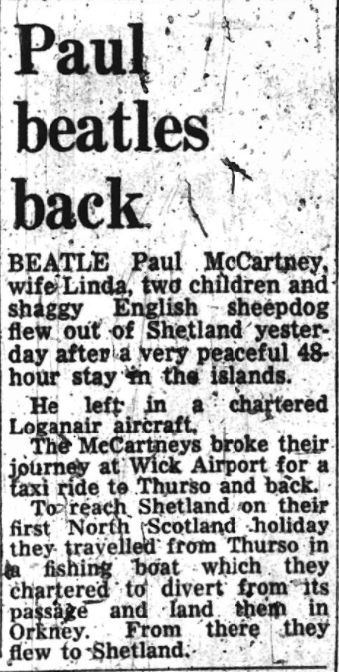

From August 2 to August 20, they went to the Shetlands for holiday.

Once it was clear that we weren’t doing The Beatles any more, I got real withdrawals and had serious problems. I just thought, ‘Fuck it! I’m not even getting up, don’t even ring, don’t set the alarm.’ I started drinking, not shaving, I just didn’t care, as if I’d had a major tragedy in my life and was grieving … And I was.

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles: Off The Record” by Keith Badmain

I went off to Scotland for a while, because I just couldn’t handle being in London, with the music business and people saying, ‘When are you going to get together with the lads, Paul?’ That was the big question. It’s like asking a divorced couple when are you going to get back together. You just can’t stand the thought of going back to your divorcee… I was a city boy, but lived far enough out of town to see a bit of the country. The farm is 600 acres and just right for the family and me. I can breathe the air. It never ceases to amaze me that I put seeds in the ground, the sun shines at the right time, the rain comes on at the right time, then something grows and you can eat it. That’s something to give thanks for… We don’t eat meat because we’ve got lambs on the farm and we just ate a piece of lamb one day and suddenly realised we were eating a bit of one of those things that were playing outside the window, gambolling peacefully. But we’re not strict, I don’t want to put a big sign on me, ‘Thou Shalt Be Vegetarian’. I like to allow myself. I like to give myself a lucky break… I just love to find that, even in this day of concrete, there are still horses alive and places where grass grows in unlimited quantities and sky has clear in it. Scotland has that. It’s just there without anyone touching it…

We were in Scotland and we decided to take a trip to the Shetland Islands, so we piled in the Land Rover with the two kids, our English sheepdog, Martha, and a whole pile of stuff in the back with Mary’s potty on the top. On the second day, we get up to a little port called Scrabster at the top of Scotland. But when we tried to get on the big car ferry, we got in the queue but we were two cars too late, we missed it. We thought, ‘Don’t despair. We really didn’t want to go on that big liner, a mass-produced thing. Let’s beat the liner,’ but we gave that up and instead we decided to try and get a ride in one of those little fishing boats. So I went to a bunch of boats but they weren’t going to the Orkney Islands, so I went on another one, this trapdoor thing, and they were sleeping down below. The smell of sleep is coming up through the door. At first, the skipper said, ‘No,’ and then I said there was thirty quid in it for him and then they say they’ll take us. It was a fantastic little boat called the Enterprise and the captain was named George. We brought all our stuff aboard and it was low tide, so we had to lower Martha in a big fishing net and a little crowd gathers and we wave our farewells. As we steam out, the skipper gives us some beer and Linda, trying to be one of the boys, takes a swig and passes it to me. Well, you shouldn’t drink before a rough crossing to the Orkneys. The little one, Mary, throws up all over Linda, as usual and that was it. I was already feeling sick and I gallantly walked to the front of the boat, hanging onto the mast. The skipper comes up and we’re having some light talk but I don’t want it. He gets the idea and points to the fishing baskets and says, ‘Do it in there.’ So we were all sick, but we ended up in the Orkney Islands and we took a plane to Shetland, it was great…

When The Beatles broke up, there we were, left with the wreckage. It was very difficult to suddenly not be in The Beatles, after your whole life, except for your childhood, had been involved with being in this very successful group. I always say I can really identify with unemployed people, because once it was clear that we weren’t doing The Beatles anymore, I had real withdrawals and had serious problems. I started drinking and not shaving. I just didn’t care. I just thought, ‘That’s the end of me as a singer, songwriter, composer,’ because I hadn’t got anyone to do it with, unless I work out another way to do it. Gradually Linda got me out of that. She’d say, ‘Come on, this can’t go on, you know. You’re good. You’re either going to stop doing music or you’d better get on with it.’

Paul McCartney – From “The Beatles: Off the Record” by Keith Badman

I was very scared. I didn’t want to give up, but it was a mess, it was unreal, and I had to handle this all by myself. There was no choice. I had to try. We had two children, we’d just been married a year, and my husband didn’t want to get out of bed. He was drinking too much. He would tell me he felt useless. I knew he was torturing himself, blaming himself for the break-up, and I was sure that he could get beyond it, but if he didn’t believe in himself, what could I do? I could only try, that’s all I could do. Let me tell you, my hands were full.

Linda McCartney – From “Linda McCartney” by Danny Fields

I was impossible. I don’t know how anyone could have lived with me. For the first time in my life, I was on the scrap heap, in my own eyes. An unemployed worker might have said, “Hey, you still have the money. That’s not as bad as we have it.” But to me, it didn’t have anything to do with money. It was just the feeling, the terrible disappointment of not being of any use to anyone anymore. It was a barreling, empty feeling that just rolled across my soul, and it was… I’d never experienced it before. Drugs had shown me little bits here and there – they had rolled across the carpet once or twice, but I had been able to get them out of my mind. In this case, the end of the Beatles, I really was done in for the first time in my life. Until then, I really was a kind of cocky sod. It was the first time I’d had a major blow to my confidence. When my mother died, I don’t think my confidence suffered. It had been a terrible blow, but I didn’t feel it was my fault. It was bad on Linda. She had to deal with this guy who didn’t particularly want to get out of bed and, if he did, wanted to go back to bed pretty soon after. He wanted to drink earlier and earlier each day and didn’t really see the point in shaving, because where was he going? And I was generally pretty morbid.

Paul McCartney – Interview with Playboy, 1984

Pitchfork: You weren’t yet 30 when you wrote and recorded Ram, did you still feel like a young man at that point?

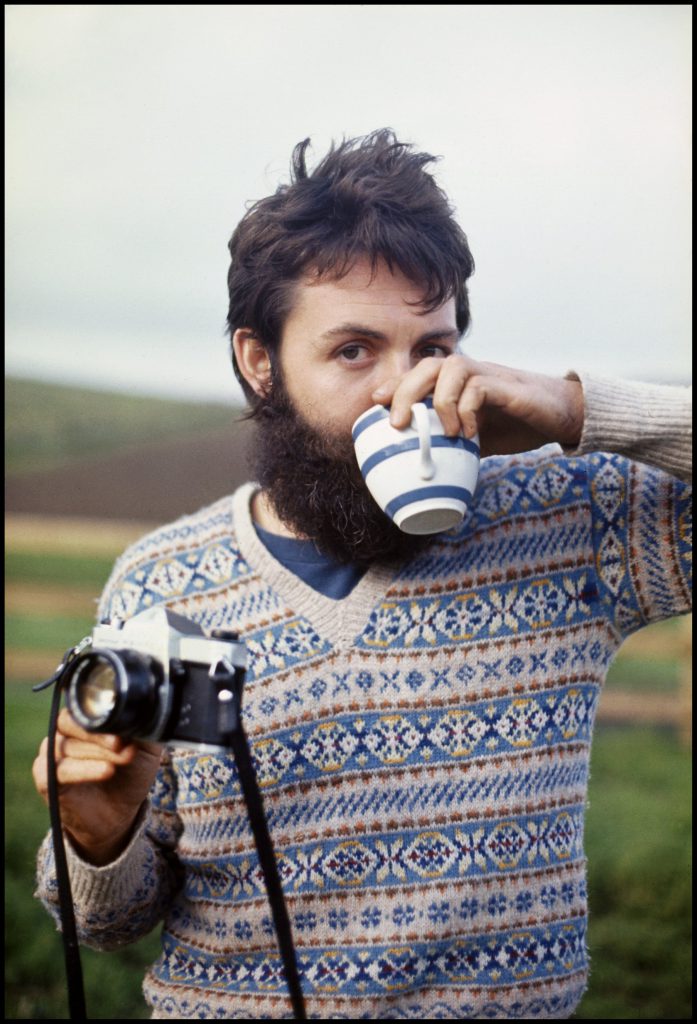

Paul McCartney: Yeah. I felt like a young man starting a new life. The Beatles had just broken up with some acrimony, and the meetings that were happening in London at the time were really heavy. It was doing my head in. So I was newly married to this lovely girl who had a great free spirit, and there I was having to go to these dreadful meetings with quite a lot of business pressure. I couldn’t figure what to do.

One day, we said, “Let’s just not go. That’ll solve it.” So we boycotted the meetings and went to Scotland, where I had a farm, and hung out there; rather than sitting around in ugliness, we split and let them try to find us. We thought, “Great, at least we don’t have to be proactive.” It felt like a hippie gap-year. It gave us an opportunity to hang with our young family that we were bringing up at the time.

Pitchfork: Why did you particularly find country life attractive at that point?

PM: It was an escape route. We went up there and did the things that neither of us had the chance to do before. Linda had been brought up by a wealthy New York family, but she was interested in nature and animals, so a free life appealed to her. I had been a Beatle for years and years– it was the type of thing where the office would buy you your Christmas tree. So the simple pleasures of getting your own Christmas tree and bringing it back home were things we never really had a chance to do. This was our chance, and we found it very joyful. I would create handmade bits of furniture because we didn’t have a bed for Mary, our new baby. They weren’t great pieces of furniture, in fact, but I liked having to be a little bit resourceful, and Linda was a great help. It was very liberating because neither of us had an opportunity to live completely freely and do exactly what we wanted. It was time for us to cut loose.

As our kids grew up, some of their friends would hear stories from this time and say, “Geez, you’re like peace convoy children.” It was a bit about this idea of a commune, which was a little in vogue at the time, and we finally got around to doing our own version of it.

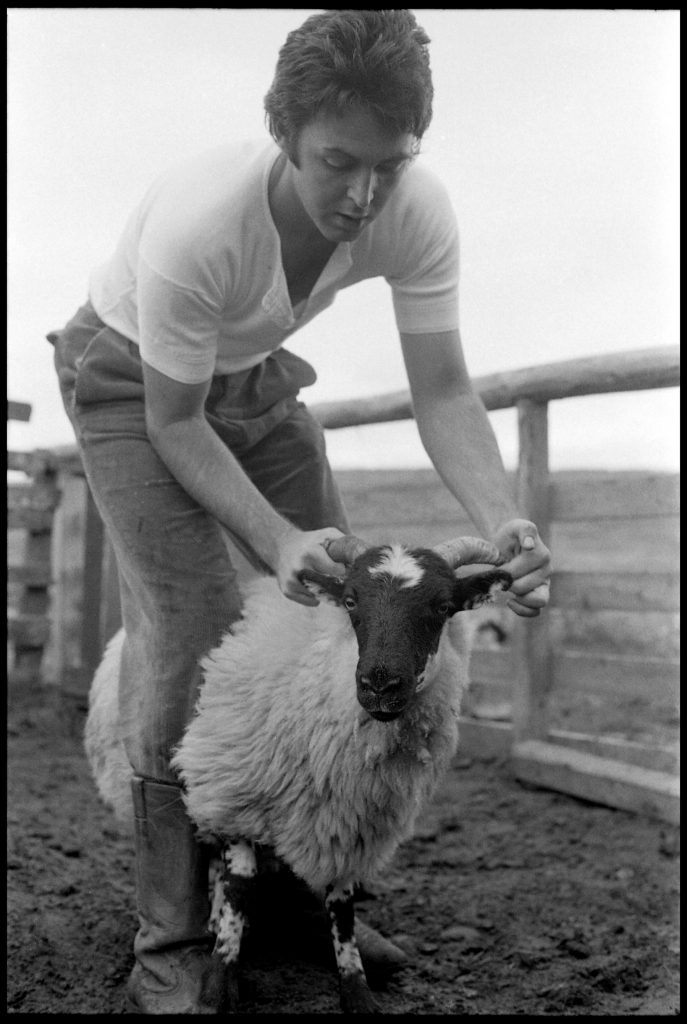

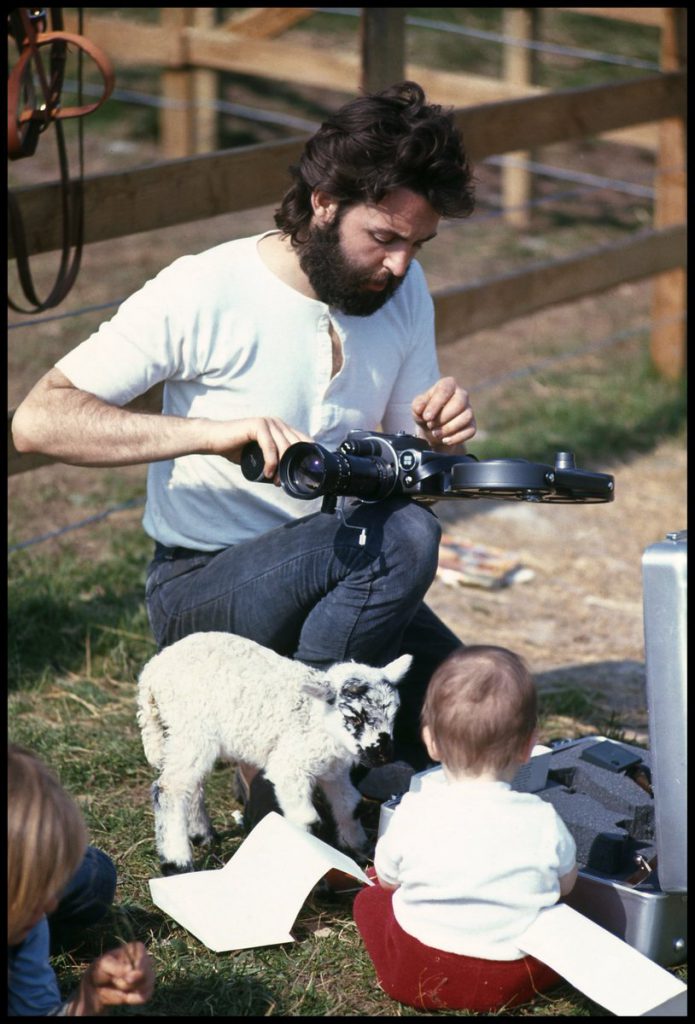

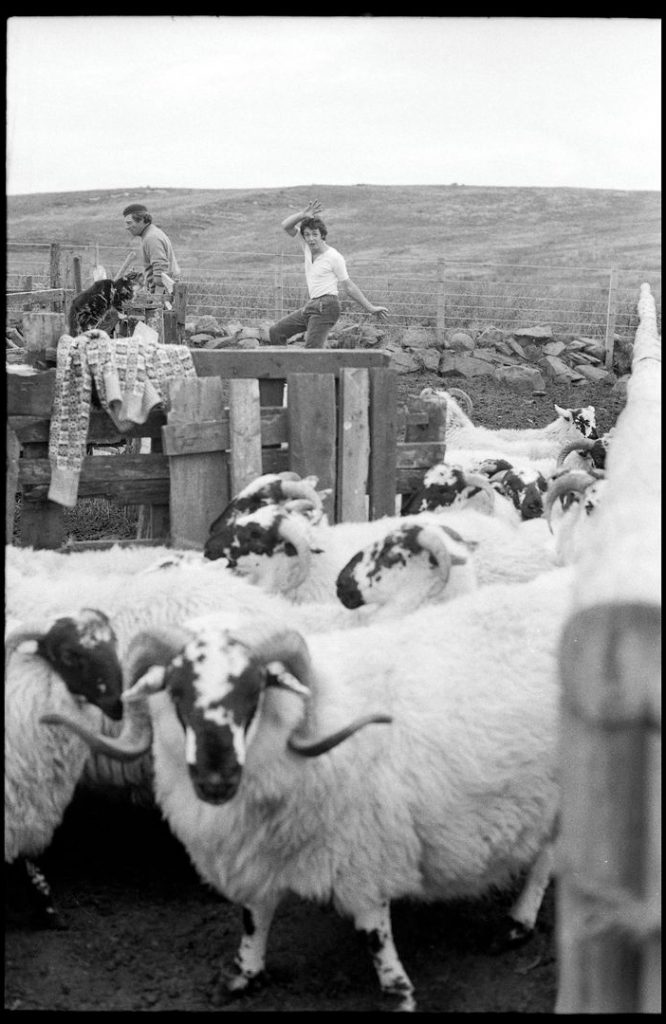

Pitchfork: As far as the farm tasks that you were doing– like shearing sheep– did you have someone teaching you how to do those things, or did you just learn them on your own?

PM: There was a guy. Don’t get the wrong idea: When we were shearing sheep, he did 100 a day, and I would do, like, five. I was definitely the apprentice. But it was great learning things like that. I had always been a nature lover as a kid, but I’d never really had any time to return to that because I had gone off into the Beatles at age 17 or so, and then into the chaos, the phenomenon, the pandemonium, the whole thing. Finally, it was time to have a little rest and go back to some of the things I had enjoyed while also learning some new skills; I wasn’t trying to become a shepherd, but it was interesting.

Paul McCartney – Interview with Pitchfork, 2012

Paul McCartney continued to write songs when in Scotland, which would lead to the recording of the “RAM” album later in 1970. Circa 2011, according to a source, a cassette tape containing 29 demos recorded during this period was re-discovered in High Park Farm.

RAM was very much influenced by our experiences on the farm – animal experiences and nature experiences. I remember bringing in a baby lamb that had been out in the field in winter and was going to freeze to death and we helped it out. And I’d never seen a curlew landing before – a curlew is a bird with a long beak, and as it comes in it lands and it’s got this lovely sound. To see those kinds of things in the wild is nice, for someone like me, and that country atmosphere lent itself to writing songs.

Paul McCartney – You Gave Me The Answer – Life on the Farm in Scotland | PaulMcCartney.com, November 30, 2021

Can you remember an average day of your life. I believe you spent a lot of time in Scotland.

Yeah, at the beginning of the album, when I was writing it, I spent a lot of time in Scotland, and the average day there would be: get up, have breakfast with the family, then maybe go into my little studio. I always had a little four track studio, which is what The Beatles always used to record on. That’s a real discipline recording on a four track, you’ve either gotta know exactly what you’re doing or you have got to start bouncing tracks. You can imagine, when you get into that, it’s addictive.

On a average day, I could have done that. I could have gone for a horse ride, as Linda was a big horse rider. At some point in the day we would have gone for a horse ride. I might have played with the kids, and they liked to go on horse rides too. Then in the evening, I’d drink whisky, of which there was a large supply in Scotland.

I do remember watching an interview where you said you maybe drank a little bit too much Whisky…

Yeah… no I did, yeah. That was kind of a feature of that time, because what happened was The Beatles, towards the end, was very constricting. You were in a corporate world suddenly, and I’m sure you know all about that. It’s not what you get into music for, but it’s there, it’s a fact of life, especially when you were the label. We were doing Apple, The Beatles ‘Apple’, and it got very heavy, so me and Linda escaped with the kids, but the business hassles were still there. So I think I was just trying to escape in my own mind. I had the freedom to have just have a drink whenever I fancied it. I’d go into the studio, maybe have another drink and so on. I over did it, basically, I got to a point where Linda had to say ‘look, you should cool it’.

Did you find at that time that you had a structured way of working? When you did McCartney I through to RAM, was that from a backlog of a big wealth of material or did you stop and have a writer’s block and then write a bunch of new material?

Some of it I had from just sitting around my house with my acoustic. Most of them, I would just sit down and write. Having written with John for all those years, we had a kind of system, which was: you just sat with a pad of paper and a pencil, and you sat at your guitar or your piano, and you make a song, and within about three hours, you should have finished the song. That’s how we always did it. So I continued to do it that way.

I remember with some songs, I would go out into the fields if it was a nice day with my guitar, so those would probably be like ‘Heart of the Country’ and the more pastoral efforts. It was mainly just what I’ve always done. Then, if I would have a writer’s block, I look back now and can say that was the over stimulation. I’d be getting like ‘heeyyyy, nice and fuzzy’ and it’s not a good thing to write. Least for me it’s not. Me and John were always very straight when we wrote, and it was normally in the middle of the day when you had your wits about you.

Looking back on it, the writer’s block that I would have occasionally, would just be getting hung up on a phrase. You know, ‘sweet little long-haired lady’, ‘fine little long-haired baby’, and you’d just go on for hours on this one phrase. What I’d do now – and I was just saying this up in Liverpool to some of my ‘songwriter students’ – is that if you ever get a block, just steamroll through it and fix it later.

Paul McCartney – Interview with Drowned In Sound, 2012

From his Scottish farmhouse, Paul is quoted as saying, “John Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr are the most honest and sincere men I have ever met. I don’t mind being bound to them as friends, I like that idea and I don’t mind being bound to them musically. I liked them as partners and I liked being in their band. But most of all, we must change the business arrangements we have for our own sanity. Only by being completely free of each other, financially, will we ever have any chance of coming back.”

Badman, Keith. The Beatles: Off The Record 2 – The Dream is Over: Dream Is Over Vol 2 (p. 16). Music Sales. Kindle Edition.

The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years

"With greatly expanded text, this is the most revealing and frank personal 30-year chronicle of the group ever written. Insider Barry Miles covers the Beatles story from childhood to the break-up of the group."

We owe a lot to Barry Miles for the creation of those pages, but you really have to buy this book to get all the details - a day to day chronology of what happened to the four Beatles during the Beatles years!

The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After The Break-Up 1970-2001

"An updated edition of the best-seller. The story of what happened to the band members, their families and friends after the 1970 break-up is brought right up to date. A fascinating and meticulous piece of Beatles scholarship."

We owe a lot to Keith Badman for the creation of those pages, but you really have to buy this book to get all the details - a day to day chronology of what happened to the four Beatles after the break-up and how their stories intertwined together!

The Beatles - The Dream is Over: Off The Record 2

This edition of the book compiles more outrageous opinions and unrehearsed interviews from the former Beatles and the people who surrounded them. Keith Badman unearths a treasury of Beatles sound bites and points-of-view, taken from the post break up years. Includes insights from Yoko Ono, Linda McCartney, Barbara Bach and many more.

Maccazine - Volume 40, Issue 3 - RAM Part 1 - Timeline

This very special RAM special is the first in a series. This is a Timeline for 1970 – 1971 when McCartney started writing and planning RAM in the summer of 1970 and ending with the release of the first Wings album WILD LIFE in December 1971. [...] One thing I noted when exploring the material inside the deluxe RAM remaster is that the book contains many mistakes. A couple of dates are completely inaccurate and the story is far from complete. For this reason, I started to compile a Timeline for the 1970/1971 period filling the gaps and correcting the mistakes. The result is this Maccazine special. As the Timeline was way too long for one special, we decided to do a double issue (issue 3, 2012 and issue 1, 2013).

Notice any inaccuracies on this page? Have additional insights or ideas for new content? Or just want to share your thoughts? We value your feedback! Please use the form below to get in touch with us.